More notes on being a foreigner (I)

Staying for any extended period of time in a country where one is obliged to speak a language other than one’s own inevitably results in reflection about core identity. Core identity, if there is such a thing, presumes that there is an ideal and comfortable state of mind, in which one is most fully at home, inside his or her own in-group, probably speaking an idiomatic form of the mother tongue among fellow-speakers, who follow the contours and references of conversation in a more or less fluent fashion, and with whom one shares beliefs, principles and occasionally political beliefs.

The foreigner, as Alastair Reid so succinctly observed, does not share this happy resource – the true foreigner, it could be argued, will feel as much a foreigner at home as anywhere else, but that is a discussion for another day – and today I returned to Reid’s essay with renewed insights. Living almost entirely within another language for most of the day, the foreigner begins to notice how language carries with it such a quantity of associative and historical luggage that merely understanding the words only accounts for a part of the fascinating, and at times frustrating problem of making oneself understood. Some of this can be accounted for by the fact that every word of a language has a personal history of association that a native speaker can trace back to childhood. Every phrase or idiom has a personal history, is laden with a particular taste or smell or music for the native speaker, and though the learner – even the fluent speaker – may acquire a series of associations of their own with the individual words of a language, it will never contain an entire universe, as does the memory of a native speaker. Moreover, the problem does not end there: as Reid wrote, “I am . . . aware of having, in Spanish . . . a personality entirely different from my English-speaking one – nor is it simply me-in-translation . . . I have often listened to simultaneous translation between two languages I know well. The meaning? Oh yes, the meaning is there; but it is just not the same experience.”

In the end, we have to arm ourselves with the anonymity of the foreigner, to prepare for disappointments and misunderstandings, and to accept that very rarely are these simply linguistic. To allow the late lamented Mr Reid the final word: “To travel far and often tends to make us experts in anonymity – but never quite, for we always carry too much, prepare for too many eventualities. One bag could have been left behind. We are too afraid of unknowns to ignore them.”

Cities Unvisited

Although he never lived in Alexandria, he had read all the books. As a young man, he visited enough of the Levant to think he knew what to expect, and concocted the rest from Cavafy, Forster, Durrell and Pynchon. Sitting outside a café in the port of Paros he fell into conversation with a specialist in unforeseen events and together they dreamed up a delivery of illicit merchandise from Lebanon to Piraeus, with a storage facility on Cyprus. His interlocutor, a Russian who in former times had skippered a cruise liner, ordered champagne. It started to grow dark. Was it there, or somewhere else, that he decided he was never happier than in an island port, as the sun goes down? Later, when he was the international figure of intrigue he was destined to become, he finally visited the city he had fantasized about so many years before. His disappointment was both intense and contradictory. Suffering suicidal thoughts, he experienced an epiphany: it was not Alexandria he was looking for, but another city, a place that he would have to invent. This almost came as a relief.

First published in New Welsh Review 103, Spring 2014

The last digression of Patrick Leigh Fermor

Reading the final ‘long awaited’ – which in this instance meant waiting for the Death of the Author in 2011 at the age of 96 – third volume of Patrick Leigh Fermor’s account of his 1934 trek across Europe, three questions occur to me about the inability of PLF to complete and publish the book while still alive.

1) the accumulation of digressions (both of writing and in life); indeed what amounted to PLF’s compulsion to digress (of itself no bad thing);

2) his failure of memory, aided and abetted by the loss of certain of the relevant notebooks;

3) an inability to contemplate the end of his journey which must, by some not-so-strange interior logic, also mean the end of his life.

An article by Daniel Mendelsohn in the current issue of The New York Review of Books also suggests a combination of factors, most particularly the digressions that formed such a substantial part of Paddy’s life and work. “We shall never get to Constantinople like this,” the author announces in a meta-textual aside, which constitutes “a humorous acknowledgement . . of a helpless penchant for digressions literal and figurative . . .”

Indeed, “the author’s chattiness, his inexhaustible willingness to be distracted, his susceptibility to detours geographical, intellectual, aesthetic, and occasionally amorous constitute, if anything, an essential and self-conscious component of the style that has won him such an avid following.”

The naivety and sheer joy of unfettered travel; the “ecstasy” that Paddy describes on “realising that nobody in the world knew where he was” – a sensation, as Mendelssohn points out, that would be practically impossible for travellers today, but which I recall from my own wanderings in the 1980s as having provoked a similarly feverish sense of total liberation; the wonderful lists that pepper his writing, eliciting new tastes and new sensations and a constant hunger to celebrate life as fully as possible; his unerring ability to stir in the reader a desire to write – which to me constitutes a failsafe criterion of all good writing; and finally – almost because of its flaws – and certainly because of what we know to have transpired in the two earlier volumes, and the unbearable anticipation of the thing – which was like a Sword of Damocles for PLF in later years – all of these help to make this book one of the most enjoyable reading experiences of the year thus far. While reading it too, I am more conscious than I was during the preceding two volumes of Paddy’s tendency to confabulate. At more than one point Paddy confesses that he cannot truly remember what happened next, but continues anyway, and even interjects passages of outrageous fantasy to spice up the story. A quotation from Javier Marías’ novel, The Infatuations, comes to mind:

“Everything becomes a story and ends up drifting about in the same sphere, and then it’s hard to differentiate between what really happened and what is pure invention. Everything becomes a narrative and sounds fictitious even if it’s true.”

Like Mendelsohn, I found The Broken Road’s incompleteness, paradoxically, to be more fitting than any neatly circumscribed ending that the author might have engineered. After so much deep description, after so many early mornings waking by the roadside with a sense of the sheer limitless possibility of the unfinished journey, after so much continuous pointless peregrination, any kind of ‘arrival’ would only have been a let-down.

While listing, above, the three reasons for the unfinished nature of the trilogy, a fourth, not entirely facetious option came to mind. Paddy famously never referred to the ultimate destination of his journey as Istanbul, but as Constantinople. Since ‘Constantinople’ did not exist under that name (nor had it, strictly speaking, since 1453), Paddy was never going to arrive. Instead we are allowed to share with him the nostalgia (which he shares with Cavafy) for a broken Hellenic world, for the ghosts of Byzantium, and a burgeoning sense of the terror that was about to descend on Europe in the years immediately following his journey.

The Pig of Babel

Saltillo has proved the most hospitable and generous city I have visited in Mexico. It seems to be filled with people who love books and actually read them, in spite of being the centre for Mexico’s automobile industry. Yesterday the temperature soared to 38 degrees by midday and my hosts Monica and Julián put on an asado – the Latin version of a barbecue – and many of the people who attended our reading on Saturday night at the wonderfully named Cerdo de Babel (Pig of Babel) turned up. The Pig of Babel, incidentally, for anyone who intends travelling in northern Mexico, is officially Blanco’s favourite bar, seamlessly marrying the themes of Pork and Borges, and taking over from Nick Davidson’s now defunct Promised Land as the most congenial hostelry in the Western Hemisphere (although I realise such a term is entirely relative and depends on where you are standing at any given moment).

The culture section for the state of Coahuila produced a beautifully designed pamphlet of five of my poems, for which I have to thank Jorge and Miquel. I would also like to offer my thanks Mercedes Luna Fuentes, who read the Spanish versions of my poems in Jorge Fondebrider’s fine translation, and Monica and Julián for the use of their and Lourdes’ home – especially since Julián had to endure my garbled Spanish explanation of the rules of Rugby Union last night, which may well have been a bewildering experience for a Mexican poet, but which I considered an essential duty of a Welsh creative ambassador.

On a different theme entirely, the fifth issue of that very fine magazine The Harlequin is now online, and it contains three new poems by my alias, Richard Gwyn, including this one, reflecting on an entirely different – but inevitably similar – journey to the one currently being undertaking.

From Naxos to Paros

Of the journey from Naxos to Paros

all he could remember

were the lights of one harbour

disappearing into the black sea

and the lights of another

emerging from the same black sea

and he thought for a moment

that all journeys were like this

but that many were longer.

Jaguars, snakes, rabbits

If you travel, Blanco thinks, if you just travel, go from place to place, walk around, you should never get bored and you should never lack for things to do or write about, if this happens to be your thing. At least that is the theory. Blanco has a minor epiphany: he must go to Coatepec (the accent is on the at): it fulfils the single major criterion he has always employed when deciding whether or not to visit a place: he likes the sound of it; it carries the resonance of something remote – in time and culture – and yet somehow reassuring. He is walking down the hill from the Xalapa museum of anthropology, and after an entire morning within its confines he has become saturated with Olmec images of human figures and jaguars and serpents, and he flags down a taxi driven by a man with stupendously fleshy earlobes; earlobes that remind him of small whoopee cushions or rolled dough or moulded plasticine. The taxi driver chats about corruption in Mexican politics. It is raining. It has been raining all morning and all last night, and throughout the previous evening, and as far as we know it has never not been raining. Outside of Xalapa there is a roadblock. The young policeman carries an automatic rifle and wears black body armour, leg armour, the works. He inspects the taxi-driver’s I.D. and stares at Blanco for several seconds. It continues to rain.

We arrive in Coataepec and get stuck in a traffic jam. Nothing moves. The taxi driver asks directions, but that doesn’t help the traffic move. Blanco spots an interesting-looking restaurant, pays the taxista, and gets out. The restaurant has a nice inner patio with a garden area, and tables around it, out of the rain. In the garden there are roses and other flowers. A large family group are finishing their meal and then spend at least twenty minutes taking photos of each other in every possible combination of individuals, so that no one has not been photographed with everybody else. They have commandeered the only waiter in order to help them in this task. Every time Blanco thinks they are about to leave and release the waiter they reconvene for a new set of photos. One of the men (a Mexican) has very little hair but a long grey ponytail, which cannot be right. One of the women – I suspect Ponytail’s sister – is married to a gringo, it would seem. He has long hair also, but not arranged in a ponytail. He speaks Spanish well, with a gringo accent. Blanco orders tortilla soup and starts leafing through a magazine he bought at the anthropology museum. His phone makes a noise that tells him he has received a message. It informs him, in Spanish: Health: Adults who sleep too little or too much in middle age are at risk of suffering memory loss, according to a recent study. He looks at the message in consternation. Too little or too much? So, hey– you’re bolloxed either way. Who sends this stuff? The screen says 2225. Then another one: Japanese fans of Godzilla were very upset with the news trailer of this film to find that Godzilla is very big and fat: read more! 3788. Then a link. Blanco shakes his head sadly.

Coatepec is full of interesting buildings with courtyards. Blanco heads down to the Posada de Coatepec, a nice hotel in the colonial style, and goes in for a coffee. A slim man with fine features, a neat little moustache, dressed in polo gear, greets him in a friendly fashion, and Blanco greets him back, once again under the impression that he has been mistaken for someone he is not. A blonde woman, also in white jodhpurs, follows the man. There must have been a polo match. How strange. The hotel offers a nice shady patio, but we don’t need shade, we just need to be out of the rain. Blanco sits on the terrace outside the hotel cafe and writes in his notebook. Before long, the man who was in riding gear comes and sits on the terrace also. Immediately three waiters attend him, bowing and scraping, one of them is even rubbing his hands together in anticipatory glee at the opportunity to serve this evidently Very Important Person. Mr Important takes off his sleeveless jacket, his gilet, and immediately one of the waiters – like a magician with a bunny – produces what appears to be a hat-stand for midgets, but is, presumably a coat-stand. Clearly the Important Person cannot do anything as vulgar as sling his coat over the back of a chair. Another waiter opens a can of diet coke at a very safe distance, and only then brings it to the table, along with a glass filled with ice. He is bending almost double, as if to ensure that his body doesn’t come into too close and offensive a proximity to the Important Person. It is one of the most extraordinary displays of deference I have witnessed in my life. Then all three waiters – the one who brought the coat-stand, the one with the coke, and the one who was rubbing his hands, a kind of maître d’ – vanish inside like happily whipped dogs. Left alone, the Important Person makes a phone call in a loud voice. He is barking instructions to some underling. He is clearly someone who is used to being obeyed, like an old school Caudillo. Must be a politician. When he has finished his call, he looks around and gets up to go inside the restaurant, where his company – family and friends, I guess – are seated. He walks inside with his drink, and within seconds one of the waiters appears out of nowhere, grabs the coat-stand, and follows him in with it.

We have to go. I have arranged to meet a poet back in Xalapa and discuss literary matters. He is called José Luis Rivas and has translated T.S. Eliot and Derek Walcott into Spanish.

Reflections on a first visit to Delhi

I like vultures. No, let me start again: I think they are vile creatures, but they are a useful reminder of our mortality, and of what might happen if we are careless enough to die in a public space at which these birds are attendant. During my brief stay in Delhi last week I had the opportunity to do very little apart from attend the First Sabad World Poetry Festival, where I was surprised (as a very minor poet) to be representing the United Kingdom – as opposed to my usual country of affiliation, Wales – alongside George Szirtes, a poet I have long admired. But, to return to my point, on the one opportunity that we were allowed out on a coach trip organised by our hosts (Sahitya Akademi, an offshoot of the Indian Ministry of Culture), I took five or six photos on my iphone in the fading light, and in two of these I inadvertently snapped vultures in flight (see below). Was this foreshadowing?

For an account of the festival itself, I can do no better than refer readers to George Szirtes’ website, where he gives a pretty full (and generous) account of what went down, especially in his analysis of the differences between the performance-oriented oral traditions of poetry and the page-oriented, European style of a one-to-one encounter between poet and reader:

“The oral tradition is rooted in the following: the community, the concept of the many and the sharing of an essentially conservative, traditional and ritualist space. The voice is public. It is heard by any within earshot. It moves into the individual’s space and occupies it, asserting its confidence in shared communal values. It can talk of private matters . . . but it does so on hallowed public ground. There is an implication of physical proximity, a swaying or flowing. The collective is greater than the individual. The poet performs a priestly role, mediating between the mass and the transcendent.

The page tradition depends on the one-to-one contract between writer and reader. The book is, most of the time, read silently and reorientated as voice in the reader’s imagination. The loud and the public are suspected of being rhetorical intrusions, acts of demagoguery, The poem is a meditated space that creates an internalised physicality that may produce a faster heart-rate, tears, finger tapping and so on but within the confines of individual sensibility. It values the individual more highly than the collective. It is to some degree, or so I suspect, an extension of the protestant sense of God as someone addressed directly without mediation. Inevitably I think of Rembrandt’s self-portraits or of the monasticism of Mondrian’s abstractions.”

I recommend anyone interested to read the whole account, and indeed to subscribe to George’s blog, which he does not call a blog, but ‘News’.

Other than attend many poetry readings, some of them good, others exceptionally dull, other still (my own session, in fact) infused with the kind of spontaneously robust anarchism at which India excels, I took notes, and I ‘networked’, but I saw very little of Delhi. There was not time. My one free day, I managed to spend shopping and chasing up an exchange dealer on the black market. I did however make several observations. I realise that none of these will be of much interest to practised India wallahs, and may even appear naive or disingenuous, but they are first impressions. The first was that I am unaccustomed to, and dislike, the sense of obligatory self-abasement or servitude imposed on the vast majority of Indians, which results in you, the European visitor, being treated with ridiculous and unearned deference. A second was that I had mistakenly expected the understanding and speaking of English to be of a higher level, especially in the service industries. But I realised after a short while that proficiency in English is pretty much limited to the professional middle classes. Taxi drivers and waiters by no means routinely speak or even understand English, as the following sample illustrates:

Blanco: Can I have a large beer please?

Waiter: Yes sir. Is that being small or big?

The third thing was vultures, which I have mentioned, and a fourth was the hell that is shopping. I will never again enter a shop in Delhi to buy anything more complicated than a packet of fags. Stress levels unacceptably high. Several people at once attempt to sell you goods you do not want, and at quite exorbitant prices, unless one is prepared to haggle, which after a couple of sleepless night, I was not. Fifth, and finally, I have always tried to avoid poverty tourism, for which reason I never went to India when most my friends did, back in the 1970s. As the Sex Pistols noted, there has always seemed to be something immoral about holidays in the sun – even under the convenient guise of the gap-year experience – when the great majority of a country’s residents live in a state of abject poverty. I know there are more ethical approaches to travel nowadays, and I attempt to follow them as best I can, but India, I fear, with its lasting resonances of Empire, will always be a difficult place for a British visitor.

On a more positive note, I mentioned in my last post the musicians from Rajasthan, who played for us last Sunday evening. I was transported by their music into a zone of almost perfect bliss. It would have been worth the airfare just to listen to them, never mind the poets. Unfortunately the sound quality of my video does not do justice to the music, so I am just posting a couple of pictures instead.

Etymology of vagabondage

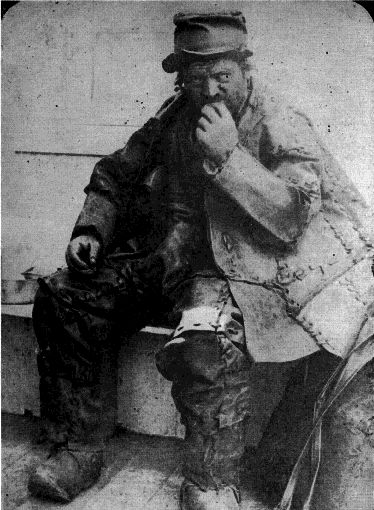

The Leatherman (ca. 1839–1889) was a vagabond famous for his handmade leather suit of clothes, who traveled a circuit between the Connecticut River and the Hudson River, roughly from 1856 to 1889.

Taken to task by a reader over the complicated etymology of vagabondage, I realise the need for another post on the subject.

In an earlier post I referred to the cirujas of Buenos Aires, otherwise known as cartoneros, those nocturnal seekers-out of trash bins, whose primary task is to find materials for recycling (plastic, cardboard, paper etc). Cartoneros are a sub-category of ciruja, a professional scavenger of all types of object for which a use or purpose can be made. That is why I likened the ciruja to a kind of street alchemist, seeking out base metal to transmute into gold. But I can see, as I was chided, that there is nothing especially poetic about this.

Whereas with the linyeras, there is. The definition of linyera given in my dictionary of lunfardo (Buenos Aires slang) is: “Persona vagbunda, abandonada y ociosa (idle), que vive de variados recursos (living off a variety of resources).” The word originally comes from the Piedmontese linger, which meant “a posse of tramps”. These fit the more romanticized notion of the classical vagabond, moving around the country (or the globe) without direction or purpose, usually associated in North America with the hobo, whose preferred means of travel was jumping trains, an occupation which was until not so long ago manageable in Europe also, but which has now become as obsolete as hitchhiking.

One still sees a posse of tramps drinking from bottles or flagons in any French town or city. These, of course, are clochards. A clochard or clocharde is a person “without fixed domicile, living from public charity and handouts.” The term clochard allegedly means ‘one who limps’ from the Late Latin cloppus (lame), but I have also heard that the term comes from the ringing of a bell (cloche) which in earlier times – when most cities in France were fortified – signalled that it was time for the indigent and poor, who could not afford lodging in town, to leave the city and go sleep in a field or a barn. To my mind, a clochard is somewhat different from a vagabond. A clochard might not venture from a known neighbourhood, while for a vagabond, the world is his lobster (sic).

According to French Wikipedia “Des vagabonds célèbres ont existé, par exemple Gandhi, Nietzsche, Lanza Del Vasto, et d’innombrables philosophes-vagabonds.”

To be continued. Any contributions welcome.

A Vagabond

The gentleman depicted here is a vagabond, from the Latin vagari, to wander.

In English the term has almost disappeared in its original sense, although a quick internet search identifies the popularity of the term to help sell niche products, for example: a wine shop in London’s West End; a Swedish shoe manufacturer; an chic boutique in Philadelphia.

A Spanish Wikipedia entry on the word vagabundo (vagabond) begins like this:

“A vagabond is a lazy or idle person who wanders from one place to another, having neither a job, nor income, nor a fixed address. It is a type familiar from Castilian literature, which contains many examples of vagabond pícaros . . .”

In the dialect of Lunfardo, which originated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries among the lower classes of Buenos Aires, the term ciruja is applied to vagabonds who collect rubbish and sort through it in search of something useful. The term derives from the word for a surgeon, cirujano. Popular wisdom has it that these vagabonds were compared to surgeons because of the way in which they carefully sought out objects of interest, picking them from trash containers and municipal tips, rather than from inside a human body. This last attribute – the meticulous extraction of some unexpected treasure from amid the rejected dross of the everyday – seems rather fitting.

In French chanson, vagabonds are typically depicted as materially impoverished characters possessed of an irresistible allure. The singer Lucienne Delyle (1917-62), one of the most popular French singers of the 1950s (her greatest hit was Mon amant de Saint-Jean) also had a song called Chanson vagabonde, which can be heard here.

Crossing Patagonia

Writers Chain tour of Argentina & Chile, continued:

After three days of readings, lectures and tea parties in Puerto Madryn, Gaiman and Trelew, yesterday we made the long trip across the Patagonian meseta to Trevelin, in the foothills of the Andes. We travelled in two cars, laden down with suitcases, snacks and literary confabulation. Our car was driven by Argentinian anthropologist Hans Schulz and contained myself, Jorge Fondebrider and Tiffany Atkinson. We endured two punctures, the first in the middle of absolutely nowhere, the second after dark on the outskirts of Esquel. The first puncture proved problematic as we could not remove the tyre despite our manly efforts. We flagged down a truck, driven by a local farmer, Rodolfo, who kindly took Tiffany and myself to the small settlement of Las Plumas, where we had arranged to meet the other vehicle, driven by Veronica Zondek, and with instructions to find a mechanic, or at least to borrow the right tools from the garage there. Having acquired these, a relief party (Zondek and Aulicino) was sent back to the stranded Schulz and Fondebrider, and the flat tyre changed, while the contingent of Welsh poets and our coordinator, Nia, waited in a roadside canteen and ate empanadas and pasta.

During the rest of the journey across the prairie, the landscape began to change. The endless flatlands of sparse bush began to erupt into extraordinary outcrops of sandstone, stalagmites of sharp russet pointing skyward, or else solid slabs of sediment rising against the backdrop of an enormous sky, across which were layered fabulous accumulations of cloud. We arrived at Trevelin at midnight, where the hospitable proprietors of the Nikanor restaurant served us leek soup and homemade ravioli, washed down with an organic Malbec wine. Around us, the snowcapped mountains provided the sensation of having arrived in a place encircled by sleeping dragons. The casa de piedra, our hotel, is done up like a Tyrolean ski lodge, with a huge fireplace in the lounge, and carved wood furnishing. We slept the sleep of the just.

Two hours into the journey we had a flat. Nearest settlement, Las Plumas, 50 km away. We were, in fact . . .

Tales of the Alhambra (or thereabouts)

Strange that in one’s memory a house takes on a different shape, a different context, becomes a dream house.

When I was living rough, a quarter of a century ago, I spent a couple of months in Granada. Along with some other homeless travellers we squatted a house on a sidestreet off Carerra del Darro, across from the Alhambra. It was a miserable building, known among those of us unfortunate to live there as ‘the house of a thousand turds’, for reasons that do not require too much explanation. But it provided some protection from the rain, and from the cold nights.

The point in this digression into my personal past is that I have often wondered about the house – or palace, as it became in my retrospective imagination: I have even wondered whether indeed it actually existed. I described its location in the vaguest of terms to Andrés, who has lived in Granada for over twenty years, and he could not think where such a palace might be. Surely it would be well-known, a palace on a hillside facing the Alhambra? It was bound, he said, to be somewhere on the Albaicín. He even mentioned consulting a local historian, who would be able to identify the mighty house from my description of it. I nodded assent, not really caring: the palace of my imagination would suffice.

It was just as well no one investigated my claim. I would have been heartily embarrassed. Last Wednesday, while walking up the hill from the Carrera del Darro (a river – actually a stream – celebrated in Lorca’s Baladilla de los tres ríos de Granada), I came face to face with a boarded-up building that immediately took me back through the years to 1988, and an appalling period of penury, sloth, craziness and some profound melancholy, living from hand to mouth – more often from bottle to mouth – through one Andalucian winter. I knew at once it was the building where I had slept. When I had stayed there, the building was already in a parlous state. It would seem that its role of providing a sleeping place for the homeless continued long after I had left the city. As one of my daughters pointed out however, the plans for restoration are well overdue. The sign apparently says the renovations are due for completion in the year 2008.

I stood back from the house and wondered at the capacity of the human brain to convert such a building into a palace. I find no answer. I have dreamed about the house, although it keeps shape-shifting. I have written about it, or versions of it. It is the opening setting for my short story ‘The Handless Maiden’, and provided the inspiration for a prose poem, which I reproduce below. But a palace it is not.

Dogshit Alley

It was my first and only visit to the artist’s apartment. He lived on the top floor. His studio offered a sensational view of the Alhambra. But first, he said, we had to negotiate dogshit alley. The artist spoke of it like one describing a secret shame. There was nothing he could do. On the third floor lived a resident who kept a wolfhound. She never exercised the dog, and let him use the landing as a toilet, which he did, prolifically. Formerly, the top flat had been empty, and no one came to visit the woman and her gawking beast. Now the artist was installed above her, and the woman had adopted the stance of long-term resident with rights. The dog, she said, harmed nobody. She seemed oblivious to the smell. The artist could not confront her. Each time he passed the landing he felt like vomiting. He tried speaking with the woman. She would stand in the doorway, the hound slavering and growling at her side. ‘Look’ she said, smiling meekly: ‘he wouldn’t hurt a fly. He’s an old softie’. She ruffled the grey fur on his head, and an incredibly long tongue flicked out and caressed the underside of her wrist. The woman smelled of gin, had white hair, parchment skin, and the smile of a ten year old. ‘He hates going out, see. He gets so scared’. The artist was lost for words. He told me: ‘I don’t know what to say to her’. When we climbed the stairs to the third floor the stench suddenly hit me. I held a handkerchief to my nose. We navigated the landing, stepping over mountainous turds. I didn’t breathe until we reached the attic studio, and walked out into the clean December air. The Alhambra stood magnificent against the backdrop of the Sierra Nevada: an impeccable statement that made me realise that it is the reproduction of a cliched image that renders a cliche, and not the original. ‘You see’, said the artist, ‘I just don’t know how to deal with her at all.’ He lived in the house of a thousand turds with a dying woman and an agoraphobic wolfhound for neighbours. This was the artist’s quandary and he could not resolve it.

(from Walking on Bones, Parthian, 2000)

Finally, on a trip to the coast, we have a modest lunch at Almuñecar, in the Manila bar-restaurant. On the way back to the car, we pass a vending machine, selling worms. That’s right: worms. Fisherman apparently puts money in the slot and a bag of live bait comes out. Who the hell thought this one up? These worms, they live inside the machine, possible for months on end. What do they do? What on earth can they do? What would you do, packed in plastic inside a vending machine? Have you ever heard of anything so extreme? Who would be a worm?

Finally, on a trip to the coast, we have a modest lunch at Almuñecar, in the Manila bar-restaurant. On the way back to the car, we pass a vending machine, selling worms. That’s right: worms. Fisherman apparently puts money in the slot and a bag of live bait comes out. Who the hell thought this one up? These worms, they live inside the machine, possible for months on end. What do they do? What on earth can they do? What would you do, packed in plastic inside a vending machine? Have you ever heard of anything so extreme? Who would be a worm?