Filibuster in Nicaragua

Of all countries of the world, there is a special place for those that have endured a suffering and a struggle for definition against powerful enemies both from within and without. Some of the struggles and mortifications that a people endure have become almost mythic and have come to stand as an example of human suffering that stretches beyond the countries concerned: they become, in a sense representative and definitive. Over the past couple of centuries there have been countless examples of the extremes of human conduct, in which small groups of people inflict their will on the majority. Nicaragua, although relatively small, must be counted among the most afflicted of countries in this respect. A series of dictatorships here have condemned the bulk of the population to obscene levels of poverty over generations, but less well known is the role played by influential foreigners. Few can compare in this respect with William Walker, the subject of an epic poem by Nicaragua’s great poet Ernesto Cardenal.

William Walker, the American son of a Scottish banker, exemplified a type of expansionist vision of what North Americans might make of their back yard, and he was evidently a scoundrel of the first order. He set out for Nicaragua in June 1855 with a small force of mercenaries and his plan was to colonise the country as a new slave state, to be settled by North American Anglos, who would own the land and the plantations, and import black slaves – who would do all the work. Eventually he planned to settle and colonise all of Central America as a slave-based empire to compensate for the abolitionist tendencies that were to drive the United States towards civil war a few years later.

His plans went well at first, his well-armed battalion of troops taking on the local army from Granada, which he made his base, before launching attacks into Leon and other regions. Walker declared himself president, invented a new flag for the country, confiscated all the lands owned by those who opposed him, made English the official language of business, and gained the recognition of the US government as head of an official state. His apparent invincibility came to an end when the Nicaraguans decided they’d had enough and rose up against him. After several bloody battles, he fled Granada by steam-boat, across Lake Nicaragua to the Caribbean, but not before his mercenaries had raped and massacred to their fill in a drunken killing spree, and burned Granada to the ground.

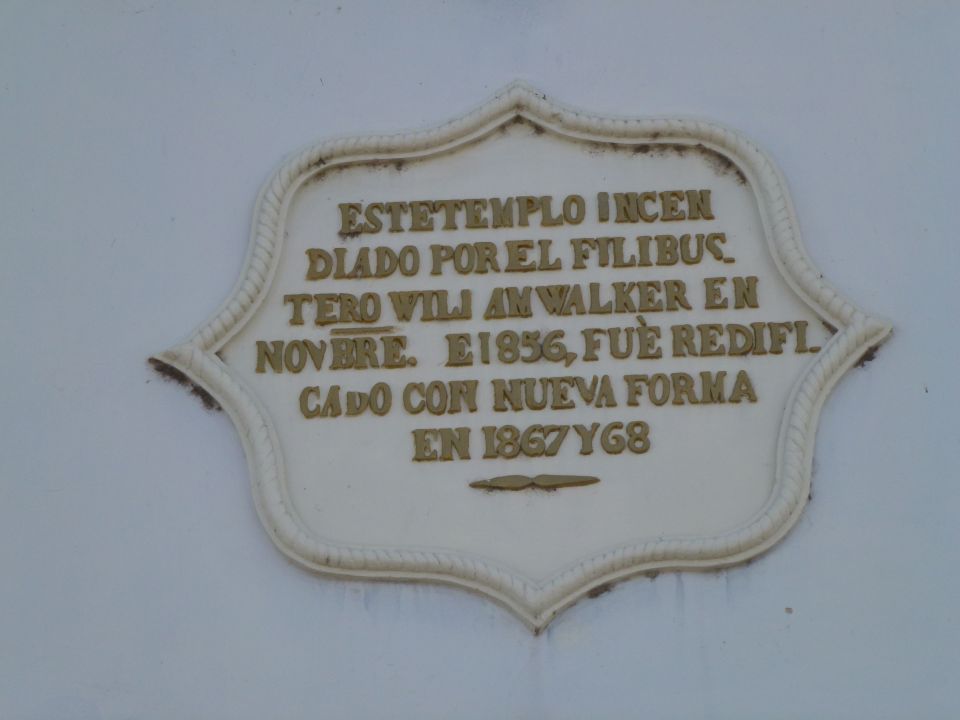

According to the plaque, the church of San Francisco was re-built in 1867, twelve years after the filibuster (delightfully, filibustero in Spanish) William Walker left Nicaragua. He had another throw of the dice in Honduras, but was captured by a British naval officer, Captain Salmon, and handed over to the Honduran authorities, who had him shot, an action that was long overdue.

The Monstrous Encumbrance

I’m not sure if there’s a suitable analogy in human terms, but imagine if ninety-five per cent of your perceptual faculties were concentrated in your snout, and then someone came along and stuck a bloody great fence around said snout, detaching your sensory facilities from the rest of your body and from the world. You would be distraught, would you not?

This is what occurred to Bruno the dog yesterday, following an operation on his front paw for an infected nail. Once the bandage was removed it was imperative that he refrain from licking his foot, the only task that interested him in the world now that he was unable to leap around and chase things.

Once we had secured the monstrous apparatus, the giant cone, around Bruno’s neck, he was so bewildered, so outraged at what had befallen him that he remained standing in the same position for three hours, without moving a muscle. For a creature that is normally a frenzied mover, an animal that proceeds with life at ninety miles an hour during all waking hours, this was some achievement. It was as if, cut off from everything that he knew and could identify, he were suddenly suspended in a kind of isolate hell. I had to go out to deliver some papers to the university, and have a swim, and when I came back, he was still there, stock still, waiting for the world to return to a recognizable form, for this ghastly hiatus to be terminated, for normal time to resume.

During the night a mournful howling awakened us, the embodiment, in sound, of infinite sorrow, and I stumbled downstairs to find Bruno in a state of abject misery. This is a dog that has never howled at night, even as a puppy. I grabbed a spare duvet and came and slept on the sofa, to keep him company, and he calmed down. I guess it must seem like some kind of torture to him. What is more, today he has to go to kennels, and quite obviously all the other dogs are going to laugh at him, I mean it’s only natural. They are like humans in that respect; mock the afflicted.

I woke up at a quarter to six after a few hours’ poor quality sleep, knowing that at four o’clock tomorrow morning Mrs Blanco and I are due to set out on a twenty-four hour trip, involving flights from Cardiff to Amsterdam, Amsterdam to Panama – what kind of person flies the dodgy-sounding Panama-Amsterdam route? I will tell you some time, but it’s not pretty – and finally Panama to Managua: I’ve done it before and it’s a bastard of a journey, though it beats going through the US homeland security farce.

So, I woke up at stupid o’clock obsessing about the giant cone attached to my dog’s neck. During my slumber, the appalling encumbrance had become an allegory, had taken on almost spiritual dimensions, and once you begin obsessing there’s nothing to do, of course, other than sit up and start writing about it.

I realise that not all my readers are going to be interested in canine matters, but that is not the point; this is not about dogs, this hideous appendage is a metaphor for just about every encumbrance we put between ourselves and self-realisation. It is about ontological crisis, a state of pure existential terror. Think about it. Pity poor Bruno.

Not unrelatedly – everything seems related some days, don’t you think? – I found myself watching a Top of the Pops from 1977 last night. Musicians featured included Thin Lizzy, David Soul and the hideous Gary Glitter, gurning and winking at the camera as he implored someone (no doubt a nine-year old Vietnamese) to hold him close. I shuddered. And how weird everyone looked: did we all look like that back then? Did 1977 really happen? Now, Gary Glitter, he would look good in one of those collar contraptions, and a padlocked gold glittering jockstrap . . . and there’s an image to travel with . . .

The resentment and insecurity of the poet

Pedro Serrano points me towards an article in the current New York Review of Books, about William Carlos Williams. In it, Adam Kirsch mentions Williams’ sense – whether it was true or not – of having been scorned by Pound, and other acquaintances, writing: “I ground my teeth out of resentment, though I acknowledge their privilege to step on my face if they could.” T.S. Eliot comes in for some particularly harsh judgement: “Maybe I’m wrong”, he wrote to Pound, “but I distrust that bastard more than any writer I know in the world today.”

And yet, Kirsch, reminds us, “If you look at the lingua franca of American poetry today – a colloquial free verse focused on visual description and meaningful anecdote – it seems clear that Williams is the twentieth-century poet who has done most to influence our very conception of what poetry should do, and how much it does not need to do.” It might be added that D.H. Lawrence carried out a very similar seminal role in British poetics.

There is much else that is good to think with in this article, some of it coming from Randall Jarrell, an acute reader of Williams, whom he considered “an intellectual in neither the good nor the bad sense of the word.” I think I know what that means, but maybe not . . .

In his autobiography Williams claims that what drove him to write was anger – somewhat like Cervantes – and his anger was clearly kept warm by his self-doubt and insecurity, his dislike or loathing of certain contemporaries (especially Eliot, of whom he claimed, late in life, to be “insanely jealous”) and his fear that he was not considered an ‘important’ poet.

How terrible the tribulations – real or imagined – of the poet, how fragile the music.

The Lottery in Babylon

In Borges’ story The Lottery in Babylon, narrated by an exile from that place, we learn that there had once been a regular lottery in Babylon, in which only the winners were announced, but that it began to lose popularity because it had no moral force or purpose, and so the old lottery was replaced by one in which there was a loser for every thirty winners. This small adjustment titillated the public interest and people flocked to buy lottery tickets. The penalty was at first a fine – which, if the loser could not pay, was replaced by a prison term – but then, as you can imagine, the desire for punishment and the administration of retribution on selected individuals became the driving force of the enterprise. Crowds love a victim: look at the stocks in medieval English towns, public hangings at Tyburn in the eighteenth century, or the popularity of public stonings and other barbarities in those places that still practice such things. In Borges’ Babylon the Company – i.e. those who administered the lottery, took control of the society and acquired omnipotence within it: the lottery came to rule the lives of all those who lived in Babylon.

Borges might well have been thinking of the role of the Catholic Church – or of any other autocratic system – when he wrote this story, but it seems to me to have a horrible contemporary relevance. Terror and misery emerge as being just as essential to human survival as the pursuit of some idiotic and unachievable happiness; the kind of elusive happiness that is offered by our own, commonplace lottery, for example, and which is announced on those absurd little TV slots where some moronic interlocutor commentates on the coloured balls as they whizz through the transparent tubes. The lottery for us is the gateway to a realm inhabited by those who have attained ‘celebrity’. Celebrity, of one kind or another, is the only good worth achieving, and the Company – interpret this as you will, but its omnipotence is terrifying – uses celebrity as a reward, but also, as we have so forcefully been reminded by the News of the World phone tapping scandal – as a punishment. Hell, of a kind: not the imprisonment or tortures endured by the losers in Borges’ story, but the pernicious and constant attentions of paparazzi and a culture of intrusion that renders the lives of all who live in the public eye (what a lovely expression) to be satirized, ridiculed and denigrated. Celebrity has replaced the religious status of the elect once occupied by bishops and popes and medieval saints, but has magnified their sufferings and their ecstasies and placed them all in the public eye. And all of it is registered, every hair of the head counted by an all-surveying Company, its cameras at every street corner.

In Borges’ story there is even ‘a sacred latrine called Qaphqa (pronounced ‘Kafka’) which gave access to the Company. In other words, there were CCTV cameras in the lavatories also.

First We Read, Then We Write

This incontrovertible statement is the title of a book I have just read about the work and ideas of Ralph Waldo Emerson – why is no one called Waldo anymore? – and a very fine book is it too, though it might not be to everybody’s taste, dwelling, as it does, on the concerns and obsessions that beset the writer going about the daily business of writing: a messy business, as a rule.

This incontrovertible statement is the title of a book I have just read about the work and ideas of Ralph Waldo Emerson – why is no one called Waldo anymore? – and a very fine book is it too, though it might not be to everybody’s taste, dwelling, as it does, on the concerns and obsessions that beset the writer going about the daily business of writing: a messy business, as a rule.

Robert D. Richardson clearly knows Emerson like no other; he swims with nimble strokes through the waterways of Emerson’s thought, and leaves you with a definite feeling for the measure of the man. I, for one, knew practically nothing of Emerson, and now, although I will find out more, my conception of him will always be coloured by the things I have learned from Richardson.

I suppose in many ways Emerson is the closest thing to an American Montaigne. Reading was his passion, but like many writers, he read ‘almost entirely in order to feed his writing’ – which is more or less the same thing as saying the two activities are contiguous upon each other: writing is simply an extension of reading, and vice versa. But reading needs to be conscious and creative: ‘Reading long at one time anything, no matter how it fascinates, destroys thought as completely as the inflections forced by external causes.’ The advice is to take only what one needs from reading, to stop as soon as it becomes a drudge or an obligation, and to read selectively, casting the dross aside.

He gave advice to many young writers on how best to keep up a journal, to be watchful and to process the material of the world like a tide mill ‘which thus engages the assistance of the moon, like a hired hand, to grind, and wind, and pump, and saw, and split stone, and roll iron.’

As for the planning of a work of fiction, his advice is right up my street: ‘You should start with no skeleton or plan. The natural one will grow as you work. Knock away the scaffolding. Neither have exordium or peroration.’

This is much what E.M. Forster meant, with the words: ‘How do I know what I think until I see what I say?’ Or Coleridge, with his appeal to ‘organic form’.

Writing should be a process of surprising oneself. If I had a plan, down to the last detail, of what my story will be, what would be the point of writing it? I mean, what is in it for me if I know precisely what is going to happen and what my characters are going to think and say and do? It would simply be a matter of typing.

So, Richardson says, ‘If Emerson’s writing does not always, or even usually, proceed in a straightforward, logical manner, it is not because he couldn’t write that way, but because he didn’t want to, and was after something different.’

Other grand quotes from Emerson:

Consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.

An institution is the lengthened shadow of one man.

Our chief want in life is somebody who shall make us do what we can.

Hitch your wagon to a star. (yeah, well, I thought it was Lee Marvin too)

People do not deserve to have good writing, they are so pleased with bad . . . Give me initiative, spermatic, prophesying, man-making words.

Every hero becomes a bore at last.

The maker of a sentence like the other artist launches out into the infinite and builds a road into Chaos and Old Night.

There is so much here that rings familiar: that we are essentially bound to nature and that all we touch and see is, at some profound level, a metaphor for ourselves. ‘The Universe is the externalisation of the soul’ – all stuff that would not have sounded odd coming from Blake. There’s a lot to take on board, which is how Emerson would have liked it. None of it is easy. Take it or leave it, but for me these writers, like Montaigne, de Quincey, Emerson, Stevenson, Proust, Borges, for whom writing was some kind of epic night journey, are almost always the most rewarding.

And what a motto (even if, like me, you have to look one of them up): Neither have exordium or peroration!

Advice to aspiring writers, and smoking by the riverside

The question – the recurrent question – asked at those events (after a reading, say, or at a literary festival) when the author is expected to wax lyrical and wise on all manner of subjects is ‘what advice would you give to a writer who is just starting out?’ I asked it myself last Monday of Peter Finch, and he gave a damn good answer – the same answer I always give – which is to read more.

Andrés Neuman. According to Roberto Bolaño "The literature of the 21st century will belong to Neuman and a handful of his blood brothers."

On his blog, Argentinian poet and prizewinning novelist Andrés Neuman (whose fabulous novel, Traveller of the Century will be available in English from February next year) says he was recently asked by a magazine to give six items of advice to beginners, and his perplexed reply was, in my loose translation, as follows:

1. Don’t conform to the patronising attitudes of older writers. They were also young, and in all probability more clueless.

2. Tradition doesn’t weigh on us, but invites us in. We write as we read: writing is a supreme form of re-reading.

3. Try, make mistakes and try again. A bad manuscript is worth far more than a supposed genius who abstains from writing, just to be on the safe side.

4. Keep correcting, to the limits of your patience.

5. Remember that we are all beginners: writing is an inaugural art and lacks experts.

6. Don’t accept six pieces of advice from anyone. One is already too many.

Otherwise – and this is completely unrelated, I was flicking through the cyberworld yesterday, and I discovered that Joseph Hill of the reggae band Culture died five years ago already, when I wasn’t looking. At the risk of going on like an old fart I remember going to see Culture at the 100 Club in Oxford Street, must have been 1977, and being knocked for six, unless that was just from inhaling the fumes from all the people who had been consorting with Mr Bong and Mr Spliff. Anyway, here is a song to remember him by.

Dog-throwing in Zapotlanejo and other rare feats

Blanco is renowned for his benevolent nature and willingness to engage in Good Works, especially the healthful encouragement of youth (or what employers insist on calling ‘community engagement’, or even worse, in the university sector ‘impact factors’ – I can barely believe I am saying this) so it will come as no surprise to learn that my visit to the Zapotlanejo High School was a resounding success.

Despite admitting to a certain nervousness in my last post, once the nettle was grasped – or the cactus, more appropriately – everything went swimmingly. First I had to meet the mayor of this small provincial town for handshakes and the obligatory photo session, and received a gift of a history book detailing the beginnings of the Mexican revolution – the war of independence against the Spanish – which was fomented in this region, we set off for the school, where, escorted by two stunningly elegant pupils garbed in regional costume, and to a deafening fanfare of trumpets, such as greets the toreador entering the bullring (I kid you not dear reader) I was introduced to my audience of 16-17 years olds..

The reality was far more pleasant than a corrida, and less bloody. After the usual embarrassing introduction, from the headmaster, I managed to blather on fitfully in Spanish for twenty minutes on the theme of ‘being a writer’ or ‘how I became a writer’, and read a couple of poems, which the English teacher, Carlos, delivered in translation. By which time I felt I’d said enough and opened it up to the floor, rather a dangerous move considering the reluctance of teenagers to be seen to respond positively under these strenuous circumstances. But they reacted marvellously, humouring me – or perhaps even taking pity – by bombarding me with civil, intelligent and even (from one gangster youth near the back) with considerable wit. The most astute question came from a young fellow in a hoodie who asked, more or less, ‘how do you know, when you get to the end of a page, that the words you have chosen are the right ones?’ Most of the kids laughed at him, but I thought it was rather perceptive, and said dammit, that’s what bothers me all the time, jolly good question my lad. So all the kids who had laughed were then booed by the kids who liked the hoodie kid. And so on. We all had a grand time. They had even made a Welsh flag especially for the occasion and some of my new fans posed with me for a picture afterwards.

My hosts insisted on taking me to a nearby Place of Historical Importance, where the first major battle of the war of independence took place, at Puente de Calderón. There, beneath the blazing Jalisco sun, I found out about the details of the conflict, explained to me by Carlos, and when I clambered through the scrub to take a picture of the bridge wondered if there were rattlesnakes – I was assured there were – and wondered yet again at the indefatigable capacity of our species to slaughter one another without respite. I also discovered a new addition to my collection of weird signs, which reads ‘Se prohibe tirar perros’, literally, ‘it is forbidden to throw dogs’, or less literally, to take them to the park and leave them there, a horribly cruel thing to do in any case, but one which encourages the formation of packs of feral dogs who then start to become a menace, as well as shitting everywhere, as Carlos explained. While there, we bumped into the local captain of police, a short but very well-built gentleman with many gold teeth. We fell into conversation and he explained to my hosts about a recent raid that he had led, and which had featured in the news. It involved an organised assault on a drug manufacturing laboratory and resulted in many arrests and a number of deaths. When they had finished, he told us, without any sense of false modesty or exaggeration, the ground outside the laboratory was carpeted with thousands of empty cartridges. He actually seemed a mellow-mannered, thoughtful fellow, but I wouldn’t want to get into a gunfight with him. ‘Mexico is a country of many faces’, said the history teacher, as we walked back to the car.

So, my respects to local culture completed, we set out to eat at a fabulous restaurant where great slabs of meat and half sheep were skewered and cooked around a blazing fire of oak. We ate and drank to the tuneful accompaniment of a mariachi band. Then it was all over and I had to return to Guadalajara to conduct Literary Affairs and to star in an event called La Mirada del Vagabundo or ‘The Gaze of the Vagabond’. It was only when the event had ended and people started to queue up to buy signed copies of said book that I realised I ought to have brought some with me. Oops.

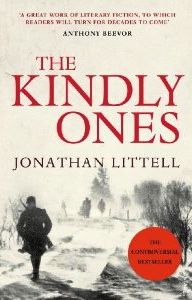

The Kindly Ones

Well, I finished The Kindly Ones on the way here, actually at a little eatery called One Flew South in Atlanta airport, the only place that wasn’t a McDonalds or a Dunkin’ Donuts. The ending was a bit of a let down: I won’t spoil it for you, but it is set in the Berlin zoo as the Russians finally take the city centre. The zoo has taken direct hits from Soviet artillery, all the animals are either wounded and bellowing or else roaming free, and Max, our narrator, gets himself into a bit of a pickle with the two rather odd Thompson and Thomson-style detectives who have been tracking him for half the book, on and off, for the alleged murder of his mother and step-father. Max conducts himself particularly badly, even by SS standards, but then he is a Lieutenant-Colonel by now, as well as quite barking. In fact his last memorable act – and this I must reveal, so stop here if you intend to read the book – is at a medal-giving ceremony in Hitler’s bunker, no doubt the last such ceremony the Führer officiated at. Max has been awarded other medals (he already has an iron cross first class for being bravely shot through the head at Stalingrad) but since he is one of the few senior officers not to have fled Berlin, they think he deserves another one:

Well, I finished The Kindly Ones on the way here, actually at a little eatery called One Flew South in Atlanta airport, the only place that wasn’t a McDonalds or a Dunkin’ Donuts. The ending was a bit of a let down: I won’t spoil it for you, but it is set in the Berlin zoo as the Russians finally take the city centre. The zoo has taken direct hits from Soviet artillery, all the animals are either wounded and bellowing or else roaming free, and Max, our narrator, gets himself into a bit of a pickle with the two rather odd Thompson and Thomson-style detectives who have been tracking him for half the book, on and off, for the alleged murder of his mother and step-father. Max conducts himself particularly badly, even by SS standards, but then he is a Lieutenant-Colonel by now, as well as quite barking. In fact his last memorable act – and this I must reveal, so stop here if you intend to read the book – is at a medal-giving ceremony in Hitler’s bunker, no doubt the last such ceremony the Führer officiated at. Max has been awarded other medals (he already has an iron cross first class for being bravely shot through the head at Stalingrad) but since he is one of the few senior officers not to have fled Berlin, they think he deserves another one:

As the Führer approached me – I was almost at the end of the line – my attention was caught by his nose. I had never noticed how broad and ill-proportioned this nose was. In profile, the little moustache was less distracting and the nose could be seen more clearly: it had a wide base and flat bridges, a little break in the bridge emphasised the tip; it was clearly a Slavonic or Bohemian nose, nearly Mongolo-Ostic. I don’t know why this detail fascinated me, but I found it almost scandalous. The Führer approached and I kept observing him. Then he was in front of me. I saw with surprise that his cap scarcely reached my eyes; and yet I am not tall. He muttered his compliment and groped for the medal. His foul, fetid breath overwhelmed me: it was too much to take. So I leaned forward and bit into his bulbous nose, drawing blood. Even today I would be unable to tell you why I did this: I just couldn’t restrain myself. The Führer let out a shrill cry and leaped back into Bormann’s arms. There was an instant when no one moved. Then several men lay into me.

The effect of this passage is shocking to the reader, in part because up to this point (we are on page 960) everything that has happened has been feasible, if not historically authenticated; Max’s experience of the massacre at Babi Yar, the battle of Stalingrad, the shenanigans among the leadership, the ostracism of Speer by elements of the SS because he wanted to deploy concentration camp inmates as armaments factory workers rather than killing the lot – most everything is the book, other than the character of Max himself, is historically based: and then this marvellous touch, with Max biting Hitler’s nose. I was so surprised I nearly fell off my chair – Demay (or was it Demaine or Deraine?) who was ‘looking after me today’ in One Flew South, was discreet enough not to ask why it took me two hours to eat a portion of sushi – and I truly thought this was an audacious move on the novelist’s part, to have his character bite Hitler’s nose. After all this tension, the massive build up of suffering and terror and slaughter, to have the whole thing brought into close-up: the suggestion that Hitler was far from a perfect example of the Aryan race he sought to perpetuate; that indeed his proboscis indicated Slavic, possibly even more degenerate racial roots, was to Max, ‘scandalous’, serves to explode the tension in a surprisingly effective way. “Trevor-Roper, I know, never breathed a word about this episode, nor has Bullock, nor any of the historians who have studied the Führer’s last days. Yet it did take place, I assure you.” I will not reveal how Max manages to get himself out of this final indiscretion, but it is quite reasonable that he does: and by this point anyway, you just want to get to the end.

Reading Jonathan Littell’s book, however, knowing how slow a reader I am, and the amount of time it has taken me while I might usefully have been employed reading other things has helped bring me to a decision: that for the next year I will only be reading short fiction and poetry. I don’t know if I can stick to it but we’ll see. If nothing else, I will acquire a new acquaintanceship with the short story, which will be fun, and certainly less exhausting.

But right now I must prepare some notes to deliver a talk to a hundred or so Mexican High School kids, on the theme of ‘How I became a writer’. Gulp. Why did I agree to this? I had the choice and could have said no. The truth is, I said it to accommodate the person who asked, at the time a distant and unknown Book Fair official. But what does it take to back out now? In future I think I will cultivate a Beckettian or Pynchonesque silence on matters of self-disclosure – not easy if one is the author of a ‘memoir’. Truly, why put oneself through this kind of thing? But then again, after The Kindly Ones, it’s bound to be a doddle.

Radio Bards and an Homuncular Misfit

Few things are quite so guaranteed to make me come out in a rash as a BBC Radio 4 poet blathering on in rhyming couplets while I’m attempting to stir the porridge. This morning I almost fell over the cat as I hurled myself across the kitchen to switch off some dementedly cheerful bard on Saturday Morning Live. I don’t think it was Wendy Cope or Pam Ayres (though I really have no way of discriminating between these people, they are all equally awful). In fact Roger McGough is not much better, or (yawn) Andrew Motion or any of the other so-called interesting poets who jolly along in a British sort of way. I can’t say I enjoy listening to poetry on the radio at all, it’s something about the terribly twee way the BBC goes about presenting the stuff, and the awfully selfconscious way that poets go about reading their work, as though they were reciting from the Bible – or worse, were super-selfconsciously reading from the Bible when pretending NOT to read from the Bible, with all those awful Eliotesque or Churchillian High Rising Tones at the end of lines that actually make me want to barf, make me want to have nothing to do with the stuff. Toxic, it is.

Which might strike you as kind of odd coming from a poet, or one who writes and performs poetry, like myself.

The problem is, I don’t really enjoy poetry readings either. Maybe one in a hundred, and then I absolutely love them. But they are incredibly rare events and I can never predict when it is going to happen. I managed to truly enjoy a joint reading by Derek Walcott and Joseph Brodsky in Cardiff County Hall back at the beginning of the 1990s. I heard an amazing reading by Sharon Olds in Stirling in 2004. I listened to a hugely powerful reading by the revolutionary poet priest Ernesto Cardenal in Nicaragua last year. But granted these were practitioners of excellence (and I have heard Walcott read on other occasions when he has not been that clever). And occasionally I enjoy cosy, informal readings by people who understand that poetry does not have to be a form of display behaviour, such as my friends Patrick McGuinness and Tiffany Atkinson, who both read very well. And a handful of others. But even the ones I like I can only abide in small doses, and even then am not certain I would be able to sit out a full-length radio performance without beginning to fidget.

The truth is, I suppose, that, unfashionably, I prefer to read poetry, in the quiet solitude of my darkened room. I prefer to read it to myself, and imagine its sounds, sometimes out loud, sometimes in my head, but in solitude: just me and the poet. Then, if I don’t like what I’m hearing I can just turn the page, or close the book; something which is not so easily achieved at a poetry reading. Even when the poetry (as at most public Open Mics) is so appallingly bad as to promote immediate self-immolation, it is difficult to leave without drawing attention to oneself. Even propelled by an immediate need to leave the room, to breathe fresh air, if not to commit some terrible violent crime or murder an innocent bystander, one risks the condemnatory glances of audience members (all of whom are aspiring bards themselves). The awful, depressing truth is that every one of the participants at these gloomy affairs believes, at heart, that they are touched by genius. If only others could see it, the world would be a better place. It makes me want to weep, honest: it is such a tragic expression of doomed human endeavour. But still.

David Greenslade is an extraordinary, shamanistic, performer of his work; and a writer of a different order. One of the most startling and memorable readings I can recall was his performance at Hay-on-Wye some years ago, surrounded by an array of glorious vegetables, items of which he would produce from time to time during the course of the event – leek, radish, rhubarb, beetroot, soil-encrusted carrot – in sequential explosions of purposeful poem-making. And his latest book, Homuncular Misfit is, true to form, both bonkers and brilliant. It is, en passant, both an evocation of the alchemical reality of the everyday, as well as a profund, and at times searing account of personal dissolution and nigredo. The sequence of poems relating to the poet/narrator’s adoption by a crow while living at a mysterious Oxfordshire manor house, or indeed a hospice, inhabited by invisible Taoist swordsmen and Chakra cleansers, the kind of place one goes for an ontological enema, is particularly impressive:

David Greenslade is an extraordinary, shamanistic, performer of his work; and a writer of a different order. One of the most startling and memorable readings I can recall was his performance at Hay-on-Wye some years ago, surrounded by an array of glorious vegetables, items of which he would produce from time to time during the course of the event – leek, radish, rhubarb, beetroot, soil-encrusted carrot – in sequential explosions of purposeful poem-making. And his latest book, Homuncular Misfit is, true to form, both bonkers and brilliant. It is, en passant, both an evocation of the alchemical reality of the everyday, as well as a profund, and at times searing account of personal dissolution and nigredo. The sequence of poems relating to the poet/narrator’s adoption by a crow while living at a mysterious Oxfordshire manor house, or indeed a hospice, inhabited by invisible Taoist swordsmen and Chakra cleansers, the kind of place one goes for an ontological enema, is particularly impressive:

. . . For a moment I thought

it might be the same bird that flew

from the glove of Mabon son of Modron

into the mouth of a shepherd

known to Henry Vaughan.

It had appeared as effortlessly as

a piece of clothing I never knew I had

until I bent to pick it up . . . .

. . . Why Crow had come, I couldn’t explain

but it didn’t go away and it did change everything

about that retreat I’d planned, considered

and thought I’d carefully arranged.

As so often occurs in Greenslade’s work, the phenomenal world intercedes in the poet’s life, seeming to take things in hand of its own accord. In his other works vegetables (as we have seen), animals (check out an article of his Zeus Amoeba here), bugs, articles of stationery, random broken things, all break in on the alchemy of the everyday and cast rationality in doubt. This time the crow follows the narrator around whenever he emerges from the house. In one poem, he contacts the RSPB and RSPCA, who both advise to scare the bird off,

But it wouldn’t go. I tried

to be as fierce as a vixen

driving off her cubs.

Defied, the crow would glide into the trees

but return within an hour.

Soon it started waiting near my window.

Unsurprisingly, the bird begins to acquire mythic status in the poet’s mind, taking on the appurtenances of a famous bird from the Mabinogion:

One night, with the hostel

all asleep, I waited mesmerised

beneath the fig tree where

Brân the Blessed perched,

Both as Bendigeidfran

and as Branwen

son and daughter

of their liquid father Llyr,

whose half-speech I now learned.

While soft, slow, pearls of rain

sparkling by kitchen light

fell in glistening strings,

dollops of scintillating guano

puddled freshly opened oysters

on the courtyard’s medieval tiles.

The crow persists, of course, and acquires an increasingly menacing aspect. But we never know how much is in the narrator’s head or how much is (ever) verifiable, because this is the borderland, the zone, the place where weird stuff happens, as Greenslade’s not inconsiderable pack of avid readers have by now learned. Elsewhere the poetry invites favourable comparison with the very best of British poetry currently being published, with a hybrid strain of influence from North American and classical Japanese poets (Greenslade lived in Japan in his twenties and is an ordained Zen monk) as well, of course, as that recurrent dipping into Welsh language and mythology. It might, gentle reader, serve as a fitting stocking-filler for an erudite beloved homunculus of your acquaintance, and is available here.