Raids on the Underworld

On 3rd December, 2024, I will be launching a Substack blog under this title.

I have been compiling Ricardo Blanco’s Blog since July 2011 and think that it’s time for a change. Which is where Raids on the Underworld comes in.

In the new blog I will be considering the craft of writing, and the ways in which writers make use of their own experiences to nourish their writing. But I will also be delving into mythology, and exploring notions such as alchemy, the latent power of objects, and synchronicity or objective chance, all of which might serve as resources for the writer (or the reader).

And I will also be posting random pieces to do with everyday life (especially walking in Wales and Catalunya), my travels, history, the world of fleeting shadows, reports from the hall of mirrors and much else besides. Though probably not a lot about shopping. Or contemporary politics. Or sport.

Everyone who is subscribed to Ricardo Blanco’s Blog – around 500 of you – will be re-subscribed to Raids on the Underworld, and will automatically receive an email with the first post. This blog will be free of charge, though after a few weeks there will probably be the option to pay a subscription for additional material.

If you do not wish to receive posts from this account, you can unsubscribe when you get the first email.

But I hope you don’t. If you enjoyed Ricardo Blanco’s Blog, the chances are you will like Raids from the Underworld.

Why not give it a try!

Richard

Invisible Dog by Fabio Morábito

This month sees the publication of my latest book of translations, Invisible Dog, by the Mexican poet Fabio Morábito.

Many thanks to the team at Carcanet for their work in producing this handsome volume.

We did an online launch on 6 November, hosted by the excellent Curtis Bauer, and featuring the poet himself — and I did a short video for Carcanet in which I talked about the translation process, which can be viewed here. But best of all, those wishing to hear some of the poems might wish to come along to Little Man in Cardiff, at 18.30 on Tuesday 3rd December, where I will be doing a reading, with the support and collaboration of the wonderful Christina Thatcher.

To whet the appetite, I will leave you with a trio of poems from the collection, in their English translations, with the Spanish below:

To get to Puebla

So many years without knowing how to get to Puebla,

which junction of which artery you have to take

to get to Puebla,

only two hours distant!

People go to Puebla and return

the same day,

I myself have been to Puebla

(who hasn’t been to Puebla?)

and so many years without knowing how to get there!

Show me how to get to Puebla,

which is two hours distant,

and to believe in God,

who is so close that He can be reached

and returned from the same day.

I myself have believed in God

(who hasn’t believed in God?)

The same thing happens with Him as with Puebla,

I don’t know which junction of which artery to take.

What has become of my life

that I haven’t learned what everyone knows:

to speak with God and to visit and return from Puebla the same day?

I only know the road to Cuernavaca,

that’s the only way I know to leave this city.

Show me the road to Puebla,

show me how to leave, to believe, to go

and return the same day.

I haven’t loved

I haven’t loved chairs enough.

I’ve always turned

my back on them

and can hardly tell

one from the other

or remember them.

I clean those in my house

without paying attention

and only with an effort can I

bring to mind

certain chairs of my childhood,

ordinary wooden chairs

that were in the dining room

and which, when the dining room was renovated,

furnished the kitchen.

Ordinary wooden chairs,

although you never arrive at

the true simplicity

of a chair,

you can impoverish

the most modest chair,

always remove an angle,

a curve,

you never get to the archetype

of the chair.

I haven’t loved

almost anything

enough,

to notice what is really there

requires an assiduous connection,

I never pick up anything on the fly,

I let the friction of the moment

pass, I withdraw,

only when I immerse myself in something do I exist

and at times it’s already pointless,

the truth has gone to the bottom of

the most prosaic pit.

I have stifled too many things

to see them,

I have stifled the shine of a thing

believing it to be an ornament,

and when seduced

by the simplest things,

my love of depth

has hindered me.

Invisible dog

I have an invisible dog,

I carry a quadruped inside me

that I let out in the park

just as others do with their dogs.

When I bend down

to let him go free,

to play and run,

the other dogs chase him,

only their owners don't see him,

maybe they don't see me either.

It happens more and more with every outing

the other dogs get worked up into a state

and among the owners a disquiet grows

and they call their dogs

to prevent a pack from forming.

Maybe they don’t see me either,

sitting on a bench,

doubled over a little

with the effort of letting him go free,

and although they can’t see him,

perhaps they do see the dog

they carry inside,

invisible like my own,

the beast they never release,

the dog that they repress

while taking their dogs for a walk.

Para llegar a Puebla

¡Tantos años sin saber ir a Puebla,

a qué altura de qué arteria hay que salir

para llegar a Puebla,

que está a dos horas!

La gente va a Puebla y regresa

el mismo día,

yo mismo he estado en Puebla

(¿quién no ha estado en Puebla?),

¡y tantos años sin saber cómo ir!

Enséñenme a ir a Puebla,

que está a dos horas,

y a creer en Dios,

que está tan cerca, que se llega a Dios

y se regresa de Dios el mismo día.

Yo mismo he creído en Dios

(¿quién no ha creído en Dios?).

Me pasa con Él lo mismo que con Puebla,

no sé a qué altura de qué arteria hay que salir.

¿Qué ha sido de mi vida

si no he aprendido lo que todos saben:

hablarle a Dios e ir y volver de Puebla el mismo día?

Yo solo sé el camino a Cuernavaca,

es todo lo que sé para salir de esta ciudad.

Enséñenme el camino a Puebla,

enséñenme a salir, a creer, a ir

y regresar el mismo día.

No he amado

No he amado bastante

las sillas.

Les he dado siempre

la espalda

y apenas las distingo

o las recuerdo.

Limpio las de mi casa

sin fijarme

y solo con esfuerzo puedo

vislumbrar

algunas sillas de mi infancia,

normales sillas de madera

que estaban en la sala

y, cuando se renovó la sala,

fueron a dar a la cocina.

Normales sillas de madera,

aunque jamás

se llega a lo más simple

de una silla,

se puede empobrecer

la silla más modesta,

quitar siempre un ángulo,

una curva,

nunca se llega al arquetipo

de la silla.

No he amado bastante

casi nada,

para enterarme necesito

un trato asiduo,

nunca recojo nada al vuelo,

dejo pasar la encrespadura

del momento, me retiro,

solo si me sumerjo en algo existo

y a veces ya es inútil,

se ha ido la verdad al fondo

más prosaico.

He amortiguado demasiadas

cosas para verlas,

He amortiguado el brillo

creyéndolo un ornato,

y cuando me he dejado seducir

por lo más simple,

mi amor a la profundidad

me ha entorpecido.

Un perro invisible

Tengo un perro invisible,

llevo un cuadrúpedo por dentro

que saco al parque

como los otros a sus perros.

Los otros perros,

cuando al doblarme

lo dejo en libertad

para que juegue y corra, lo persiguen,

sólo sus dueños no lo ven,

tal vez tampoco a mí me vean.

Se ha ido dando a fuerza de paseos,

anima e inquieta a la perrada

y entre los dueños cunde la inquietud

y llaman a sus perros

para que no se forme la jauría.

Tal vez tampoco a mí me vean,

sentado en una banca,

doblado un poco

por el esfuerzo de dejarlo libre,

y aunque no pueden verlo,

tal vez sí ven al perro

que invisible, como el mío,

llevan dentro,

la bestia que no sacan nunca,

el perro que reprimen

llevando de paseo a sus perros.

Further reflections on waking at 4.00 a.m.

Two more things emerged from stirring the 4.00 a.m. pot, an unsought consequence of which. last night, was a long bout of sleeplessness and some scribbled notes. A couple of these will serve as an addendum to yesterday’s piece.

The first comes from Rachel Kushner in her new, Booker short-listed novel, Creation Lake.

At one point in her story (p. 209) Kushner’s narrator, Sadie Smith — an undercover agent provoking disruption at a protest by eco-activists in southern France — pauses to reflect on the notion of identity:

‘It is natural to attempt to reinforce identity, given how fragile people are underneath these identities they present to the world as “themselves.” Their stridencies are fragile, while their need to protect their ego, and what forms the ego, is strong.’

Her conclusions are striking:

‘People might claim to believe in this or that, but in the four a.m. version of themselves, most possess no fixed idea on how society should be organised. When people face themselves, alone, the passions they have been busy performing all day, and that they rely on to reassure themselves that they are who they claim to be, to measure their milieu of the same, those things fall away.

What is it people encounter in their stark and solitary four a.m. self? What is inside them?

Not politics. There are no politics inside of people.

The truth of a person, under all the layers and guises, the significance of group and type, the quiet truth, underneath the noise of opinions and “beliefs,” is a substance that is pure and stubborn and consistent. It is a hard, white salt.

This salt is the core. The four a.m. reality of being.’

The second piece of feedback from the universe came in the form of an article in The New Yorker, by Alan Burdick, writing in 2016. Burdick is also the author of the book Why Time Flies: A Mostly Scientific Investigation. In the extract that interests me, he is commenting on the uncanny way in which the seasoned insomniac — or anyone prone to sleep disruption — somehow knows what time it is when they awaken at night. Sometimes, or rather, often, to the precise minute. How does that work?

For Burdick, ‘it is always 4.00 a.m., or 4.10 a.m., or once, for a disconcerting stretch of days, 4.27.a.m.’ He quotes Proust, that maestro of insomnia, who wrote: ‘When a man is asleep, he has in a circle around him the chain of the hours, the sequence of the years, the order of the heavenly bodies. Instinctively he consults them when he awakes, and in an instant reads off his own position on the earth’s surface and the time that has elapsed during his slumbers.’

But, beyond the poetry of the heavenly bodies and our own instinct, just why do we awaken so consistently at precisely the same time?

Burdick, writing of his own case, says: ‘It may . . . be a simple matter of induction: it was 4.27 a.m. when I last woke at whatever hour this is, so that’s what time it is now. The surprise is that I can be so consistent. William James wrote, “All my life I have been struck by the accuracy with which I will wake at the same exact minute night after night and morning after morning.” Most likely it’s the work of the circadian clocks, which, embedded in the DNA of my every cell, regulate my physiology over a twenty-four hour period. At 4.27 a.m., I’m most aware of being at the service of something; there is a machine in me, or I am a ghost in it.’

Beyond that, it’s difficult, or even pointless to hypothesise. I continue to wake at precisely the same time for a stretch, until I don’t. And then, of course, whenever I notice it’s that time again — 3.45 in my case — I make a mental note of it, as if acknowledging someone we pass at the same place each day on the way into work, but never get to know.

Illustrious insomniacs: 4.00 o’clock or whatever time in the morning

It sometimes happens that, as soon as I decide to write about something, the universe sends me little pointers and reminders, as if to corroborate the idea. Call it serendipity or call it synchronicity; whenever an idea looks like having legs it will start to attract some kind of corroboration in the things I read or see or hear around and about me. No less a person than Goethe commented on this when he wrote that once one commits oneself throughly to a task, then Providence moves too: ‘All sorts of things occur to help one that would have never otherwise have occurred. A whole stream of events issues from the decision, raising in one’s favour all manner of unforeseen incidents, meetings, and material assistance which no man could have dreamed would have come his way.’

And if by chance Providence doesn’t move in my favour, I tend to forget about it, or rather, having committed myself to a certain kind of magical thinking, and not receiving any feedback from the universe (or Providence) I give up and choose another tack.

But 4.00 a.m. has proved a kind of anti-beacon, a proper misery magnet. Almost everyone has something to say about it; everyone, that is, who happens to be an insomniac. Because for insomniacs, 4.00 a.m. is Prime Time.

A quick scan of the literature supports this idea, and where better to begin than Marie Darrieussecq’s wonderful book, Sleepless, which I have mentioned before in these pages. In fact, a section of Sleepless is titled FOUR O’CLOCK OR WHATEVER TIME IN THE MORNING, which I have appropriated for this piece also.

The first insomniac on the guest list is Kafka, suffering ‘agonies in bed towards morning. Saw only solution in jumping out of the window’, swiftly followed by the ‘career insomniac’ Emil Cioran, whose notebooks contain similarly suicidal ideation: ‘Shocking night, At four in the morning I was more awake than in broad daylight. Thought about Celan. It must have been on a night like this when he suddenly decided to end it.’

Like a slow train chugging towards its unknown destination on a night of fog and rain, Marie Darrieussecq counts us down to zero hour: ’Two o’clock, three o’clock, four o’clock. Insomnia without end.’

Marguerite Dumas, another elite member of the literary insomniac gang (and an alcoholic whose routine intake of vin rouge in her heyday was seven bottles per diem) adds her piece: ‘During serious bouts of insomnia, one says to oneself: “If I died this instant, what a relief that would be.”’ And the worst time, she writes, ‘is around three or four in the morning.’ Christian Oser, meanwhile, muses that ‘to die at four in the morning, in the discomfort of insomnia, constitutes a form of temptation, the hope of bailing out and coming to terms with silence.’

There is, writes MD, no end to this four in the morning literature. F. Scott Fitzgerald, another insomniac (and another drunk — many of the most illustrious insomniacs have also been addicts of some kind) puts in his tuppence worth: ‘What if this night prefigured the night after death . . . I am a ghost now as the clock chimes four.’

And as for music . . . in one of those instances of serendipity that I referred to at the start when the 4.00 a.m. idea was only a twinkle in my eye, someone played a recording of Mike Oldfield’s 1983 song Moonlight Shadow (performed by Maggie Reilly) which contains the tautology ‘Four a.m. in the morning’ (when else would it be?) . . . except 4.00 a.m. isn’t exactly the morning, it’s more of an island in time, a non-place, but a place visited, or rather squatted, by innumerable insomniacs. And another musical reference is, of course, the opening of Leonard Cohen’s Famous Blue Raincoat: ‘It’s four in the morning, the end of December, I’m writing you now just to see if you’re better . . . ’, a song that accompanied me on my most tormented nights as an angst-struck teen.

In my novel The Blue Tent, the insomniac narrator is visited in his library at precisely a quarter to four by his mysterious house-guest, Alice. This specificity, I may as well confess, came about because at the time I was working on the story I was prone to waking at exactly 3.45 myself, and I wondered whether by turning it into fiction, it might stop happening (it did). Magical thinking in action.

The Future is Dark: Woolf, Solnit, Darrieussecq . . . and the Lucy Letby trial

These words were cast before me by a triad of women writers, each of whom has had a significant influence on my thinking at one time or other: Marie Darrieussecq, Rebecca Solnit and Virginia Woolf.

Marie Darrieussecq opens the penultimate paragraph of Sleepless — her inspired, rambling study of insomnia — with a line from Virginia Woolf’s journal of January, 1915: ‘The future is dark, which is the best thing the future can be, I think.’

It is a sentence that has prompted a great deal of speculation over the years, including an essay by Rebecca Solnit, which Darrieussecq acknowledges in a footnote. But it was the first time I had come across the quotation, and I wondered at it, and wondered about it, and was pleased to find that I already had a copy of Solnit’s essay on the bookshelf next to my desk; but first I should recount what Darrieussecq has to say about the line, which was written in 1915 after Woolf had taken an overdose of veronal, a commonly prescribed barbiturate at the time. She locates that darkness, firstly, as seems proper, in Woolf’s own subjective experience; and then pans out, seeing the world that Woolf herself saw around her, but knowing — as Woolf did not know — that the horrors of World War One would continue for another three years, and would be followed by the global pandemic of Spanish Flu and, Darrieussecq reminds us, more years still of darkness, “if we count what will follow and what is simply the same sequence: ‘crisis’, fascism, war . . .” She completes her digression with a suggestion, or a remedy: “We can get through the shadows in the present, step by step. Do away with nostalgia for the future, the famous future of ‘progress’ that gleamed in my childhood, with its senseless promise of growth. Change the image of the future, even a tiny bit, shift ourselves ever so little, a small sidestep — that’s what literature is for. An enormous ambition, and yet a modest one — in order to wake up slightly different.”

And here is where I must pause, because of the shudder of recognition I felt with that line about progress, and what it means to Darrieussecq’s generation and my own and to most of the generations that have been born in recent centuries, at least since the idea of ‘progress’ became fashionable, some time in the Renaissance. And to link that notion with ‘darkness’ — now, in 2024 — seems interesting, to say the least. But then again, there is a lot we hold in common with the years immediately preceding World War One, not least of which is a profound and vague sense of impending catastrophe.

* * *

I have been reading, rather compulsively, everything I can find about the case of Lucy Letby, the neonatal nurse convicted of the murder of seven small babies, and of trying to murder six others. I started with the 13,000 word New Yorker article, which I accessed without difficulty since I am currently in Spain (it is impossible to access the article from the UK, except through VPN, as it has been subject to a special reporting restriction under the Contempt of Court Act). I mention this not out of any need to wilfully promote non-sequiturs but because the Letby case seems to me very relevant to a discussion about the future being dark, or darkness in general. For the parents of those dead babies the future has already been significantly darkened, and as for Lucy Letby, what could be darker than the prospect of a lifetime behind bars, with no possibility of reprieve, condemned not only to prison but subject to the hateful scrutiny of an entire nation? The murder of newborn babies might be seen as the most heinous of crimes, not simply on account of the innocence of the victims, but because throughout history human societies have regarded children as constituting the future, and consequently ‘hope for the future’. In a broken society, a society on its knees, with the remnants of a once proud Empire consigned to the refuse dump of history, with climate catastrophe at the doorstep, any sense of the future is fragile, to say the least, so the presumed murder of numerous infants takes on an especially tragic and symbolically laden aspect. The killer of children is a monster, murdering a future that is already of dubious status and therefore to kill small children is to kill the future twice over. Rather than concede that the cause of the infant deaths, horrible as they were, might reside, for example, with systematic failures in the administration of a hospital department within a health service on the verge of collapse, how much easier and more satisfying it is to point the finger at an individual, a single twisted individual, so cunning, it would seem, that she fails to possess any of the traits normally associated with serial killers, or even with expert actors, and appears to lead a normal, sociable life, popular with friends and loved by her parents. And how much simpler for the powerful men running the department of the hospital where she worked to blame an individual — a young woman, it should be emphasised — rather than concede that possibly, just possibly, the deaths might have been brought about by a combination of bad luck and errors of judgement in a neonatal department struggling with the pressures brought on by a chronic shortage of staff and funding . . .

Obviously I don’t know why those babies died, but it’s the uncertainty of the conviction that concerns me and many others. Certainly we don’t want to fall into the same trap as Lucy Letby’s accusers, and be overly assertive or accusatory, but we do need to look over the evidence again, with a better informed set of expert witnesses.

* * *

Let’s take another look.

“The future is dark, which is the best thing the future can be, I think,” Virginia Woolf wrote in her journal on January 18, 1915, when she was almost thirty-three years old and the First World War was beginning to turn into catastrophic slaughter on an unprecedented scale that would continue for years.”

So begins Solnit’s essay, ‘Woolf’s Darkness’. Solnit’s essay proceeds by locating Woolf within the context of her mental illness and the war, and declares that the sentence with which she opens “is an extraordinary declaration . . . a celebration of darkness, willing — as that “I think” indicates — to be uncertain even about its own assertion.”

Solnit goes on to remark on the associations we make with the dark and darkness. How many of us, especially children, fear the dark, and yet, at the same time, darkness forms “the same night in which love is made, in which things merge, change, become enchanted, aroused, impregnated, possessed, released, renewed.”’ We might add that as night falls, thoughts of death, our own death, are likely to emerge. We might even start thinking about death in the same moment, no, in the instant immediately preceding the moment in which we feel the desire to make love: the two things seem to be inseparable, as the ancients knew with the eternal dichotomy of Eros and Thanatos. But Solnit does not labour this point: instead she tells us how, when starting out on the essay we are now reading, she picked up a book on wilderness survival (suggesting, perhaps, that we often pick up books at exactly the right time) and found the following sentence: “The plan, a memory of the future, tries on reality to see if it fits.” This reminds her how, despite the warnings reality has to offer, we often dive into darkness, into oblivion, because we have made our minds up, we have made a plan, and we are prone to accommodating new information as simply confirming our pre-existing mental models. As she puts it: “under the influence of a plan, it’s easy to see what we want to see.” She quotes the book on wilderness survival (by Laurence Gonzales), which reports that “people tend to take any information as confirmation of their mental models” — which has a particular significance when we consider the Lucy Letby case, especially the evidence given by the consultant, Dr Ravi Jayaram who was the first to suggest that Letby might be a murderer. He described watching Letby as she stood by the end of the bed “doing nothing”, as blood oxgyen levels dipped but no monitor alarms sounded. Rather than allowing this moment of inaction to harbour other possibilities — thinking about what course of action to take being first among them — Letby’s inaction helped to confirm her as the murderer, presumably because the idea had already burrowed its way into the minds of her accusers, and of the jury, that she was to blame.

Solnit goes on to suggest that the darkness does not pertain merely to the future, but to the past as well. We cannot know exactly what happened in the past if we were not there, nor can we make authoritative claims about other cultures (and the past is another culture as well as another country). “Filling in the blanks replaces the truth that we don’t entirely know with the false sense that we do.” And “the language of bold assertion is simpler, less taxing, than the language of nuance and ambiguity and speculation.” (And how that sentence resonates when applied to the Lucy Letby case). Planning and the idea of the future (and planning out how the future should unfold) can cause an expectation in the present that may bear no resemblance to the way things actually happen, or happened in the past.

Perhaps there is not a lot more to be gleaned from Woolf’s enigmatic sentence (written, after all, in a private journal, where we often leave all kinds of half-formed and speculative sentences) other than the suggestion offered by Solnit that “we don’t know what will happen next, and that the unlikely and the unimaginable transpire quite regularly.” In this sense, ‘the future is dark’ does not seem such a daunting phrase. Perhaps (again) it simply means ‘the future is uncertain’. Both despair and optimism are grounds for non-action. From here it is an easy step to take (as Solnit does) and meet with John Keats walking home with some friends one night, for whom several things dove-tailed in (his) mind, and the phrase ‘Negative Capability’ came about, by which Keats meant when one “is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.” In other words, life is not so much a problem to be solved, as a mystery to be experienced. It is significant too, in Solnit’s reading, that Keats’ discovery came out while walking, and that “wandering on foot can lead to the wandering of the imagination and to an understanding that is creation itself”, an assertion with which Woolf would no doubt have agreed, what with her own habit of wandering, made famous in such essays as “Street Haunting.”

And it is not only a wandering of the imagination that is prompted by such excursions, as Woolf makes clear in that same essay. In the evening hour, especially, the time that the French call l’heure bleue, we are granted a certain irresponsibility, a gift bestowed by darkness and lamplight, with the result that “we are no longer quite ourselves.”

Much of the rest of the essay is given over to various instances of Woolf stating that she doesn’t know things. At one point Solnit remarks: “By now you’ve noticed that Woolf says ‘I don’t know’ quite a lot.” But in that not knowing there is a great deal of wisdom, and that, I think, is the point.

That, and a kind of enthusiastic acceptance that there is always more to things than meets the eye, even if we do not know precisely what: “All Woolf’s work as I know it constitutes a sort of Ovidian metamorphosis where the freedom sought is the freedom to continue becoming, exploring, wandering, going beyond.” The catastrophe of climate change, the destruction of our Earth are due, in large part, to a failure of the imagination. Solnit’s plea is that we pay attention to what matters even if it cannot be seen, and that we become “producers rather than consumers of meaning, of the slow, of the meandering, the digressive, the exploratory, the numinous, the uncertain.”

And here, where darkness lies, the future opens up before us.

Let us hope, too, that Lucy Letby is given another chance to assert her innocence. The notion that she might have been wrongly convicted, and endured the most horrendous hate campaign in living memory, is awful beyond words, and a retrial is the very least that can be provided if there is even the slightest possibility that she might be innocent.

To be always the same person

I have driven past Bryn Arw countless times on my way to the Vale of Ewyas and Llantony, but only became aware of it as a separate entity about three years ago when a graffito appeared on the hillside, carved, as it were, into the ferns: ‘Daw eto ddail ar fryn’ — which means ‘There will be leaves on the hill again.’ The line is a play on words, intentionally mis-quoting a line of poetry popular across Wales during lockdown – ‘Daw eto haul ar fryn’, meaning ‘There will be sunshine on the hill again’. The words were carved into the hillside by a local charity called ‘STUMP UP FOR TREES’ / ‘CEINIOGI’R COED’ who are intent on an ambitious replanting programme that will help improve biodiversity in the area. They hope to plant one million trees on hillsides and marginal agricultural land across the area.

I walked Bryn Arw for the very first time last Christmas Eve. It turned out to be the windiest of days, and I set out along with a few family members and a borrowed dog, a scruffy but amiable mutt named Bluey. We all needed to get out of the house before Christmas indolence melted our brains. First we hugged the lower reaches of Pen-y-fal, or the Sugar Loaf, before turning east and climbing to the long ridge of Bryn Arw. Here we were so buffeted by the southwesterly wind that it felt almost as if the next gust might lift our bodies from the ground and drive us high into the air, depositing somewhere in the green fields of Herefordshire.

The strange thing about walking Bryn Arw is that, never having walked it before in this lifetime, I have no memories of it, unlike almost all the other walks I do around these hills. And that, I realise before we are half way up, makes a difference. When I am walking around Llantony or Capel or Ffin or the Grwyne fechan valley, I am brushing up against the countless versions of myself left hanging around from previous excursions. At times a sense memory washes over me of having been present at this spot many times before, and that makes a difference. How does it make a difference? How does it ‘feel different’ on Bryn Arw to being in a place you know intimately? ‘The difference is that on Bryn Arw I am, after a fashion, a new version of myself and have no comparators. I am aware of being in a new place with distinct perspectives and views of the hills around about. For example, looking out towards Partrishow hill and Crug Mawr behind it, I am looking at places I know well from a new angle, and that seems to correlate precisely — albeit in a rather minor way — with occupying a distinct version of myself from the one on previous visits.

In his Meditations, Marcus Aurelius considers it a virtue “to be always the same man” , which suggests to me as much a Roman adherence to manly qualities as an insistence on a continuity of self. But in order to be always the same person one needs to be in possession of a sense of self in the first place, one that is continuous over time. However, it seems clear to me when considering an event or series of occurrences in my past, that the ‘I’ that is doing the remembering in the present is not the same ‘I’ that is being remembered. Or, to put it slightly differently — and following on from an argument famously put forward by Galen Strawson — they might have happened to Richard Gwyn but they didn’t happen to me, as I am in this moment.

This perception of ‘myself’ is further complicated by the fact that at key, or seemingly pivotal points in my life I have always experienced a strong sensation that I am detached from myself in a significant way, as though looking on from a slight distance as ‘I’ — the physical entity I recognise as RG — undergoes stuff happening. Thus I am these two distinct entities — the experiencing self and the detached disembodied thing that is also ‘I’ but somehow independent, ‘above’ or ‘outside’ of me, and yet simultaneously the most intrinsic, innate version of ‘me’ (at least as far as I can tell: it is quite possible that within the lifeworld of that more intimate, innate ‘me’ lurks yet another more intrinsic version, and so on, peeling away the versions like onion skins). When looking in the mirror, for example, the physical form that looks back at me — RG, to others — is somehow ‘not me’, but the form or person that I temporarily inhabit. This corresponds with the idea that sometimes I am observing myself thinking, and even observing myself as if from outside myself, as described at one or two points in these posts. I imagine this is fairly common, but I don’t know or whether its increasing frequency in my life might be accounted for by my historical consumption of mind-altering drugs, or some other cause, such as the recurrent insomnia from which I have suffered for much of my life. Perhaps this is significant. Insomnia brings about a sense of detachment, an impression that nothing is quite real. I was reminded of this, coincidentally, by watching the movie Fight Club the other night, when the narrator comes out with the line: ‘With insomnia nothing is real. Everything is far away. Everything is a copy of a copy of a copy.’

I’m sure we have all had similar moments, when our sense of detachment from the body — or even the ‘person’ inhabiting that body — is more pronounced, even to the point of feelings strangers to ourselves. On a certain level this happens to us incrementally as we get older.

And I am wondering, as we prepare to move home: how does being in a new place affect not only awareness of your surroundings but also, correspondingly, self-awareness? We often slip into complacency, or a kind of non-seeing when in familiar places, but in a new place — as a tourist, or walking in an unfamiliar landscape — we tend to be more alert, taking in details of our surroundings with a heightened intensity. In some ways, this perception of familiarity versus strangeness carries over into our perception of ourselves within those spaces also. It is as though we harbour the ability to be more aware, or more mindful when the circumstances demand it, or else when we choose to be. And this is something that is useful for writers. When I taught writing classes I would sometimes send students out to write at a cafe in Cardiff market or in one of the arcades, and imagine that they were seeing the scene before them for the first time — as a stranger or a ‘foreigner’, in the extreme sense of the world (someone with no bonds of belonging, someone truly lost). To write from the perspective of one who sees everything for the first time.

Curiously — as though this were a recurring obsession — when I was nineteen, I wrote a short story about such a person, a man who each night forgets everything about himself, his life and his surroundings. But I lost the story or else threw it out. It turned out there was not a lot to say about this man other than that he forgot everything. As such, I was pulling the rug of storytelling from under the feet of my protagonist before I started, since all storytelling resides in memory.

Narrative Horror

A conversation with an old friend, while driving to Bristol airport earlier this month, led me back along the wild mountain tracks of memory, and an introduction to what psychologist Martin Conway refers to as the self-memory system (SMS) model of autobiographical memory.

In an article published in 2005 titled ‘Memory and the Self’, Conway argues that two of the central concerns of memory are correspondence and coherence. Correspondence refers to the essential accuracy of what we recall, and how we remember (or at least recount) our experience. Coherence, on the other hand, is the requirement to make our memories consistent with our current goals, beliefs and self-image. Conway’s insight lies in reminding us how personal memory is as often as not a trade-off between the distinct but competing demands of coherence and correspondence, between adhering to our contrived self-image at the same time as (supposedly) telling the truth about our past. This can often be an uncomfortable compromise. If the self-image is threatened by the inconvenient fact of contradiction, what is a person to do? It is easy to see how the serial fantasist simply invents new stories in order to bridge the gap between who they think they are and what actually happened.

Thinking about all of this, I am reminded of what Javier Marías terms El horror narrativo (narrative horror), the way in which one’s status, as well as one’s accomplishments and merits, can be tainted or destroyed by a single misfortune or a single moment of disgrace — when we have committed some deed for which we will never be forgiven, and for which we might not even be responsible, but which has been imposed or inflicted on us by others. Either way, every aspect of our life story’s, carefully nurtured up till then, can be overturned, thrown into question, or brutally exposed and ridiculed, all in an instant. The most obvious example of this, according to Marías, might be the way that a public figure, overly self-conscious of being such a big shot, might worry about events in their past lives and the way they might appear to others, if discovered — to such an extent that they live in terror that a moment of narrative horror might descend upon them and reveal to the world just what an abject individual they really are, how ill-suited they are to public office, and of how their lovingly tended self-portrait will be forever tainted by some indiscretion that ends their career. Sometimes, Marías reminds us, this can happen posthumously, for example when secrets are discovered that were kept safe during the individual’s lifetime. But as much as anything else, narrative horror overcomes us when the factors of correspondence and coherence do not meet up, and we are left with our narrative torn apart and shown to be an utter fiction after all.

Javier Marías (1951-2022)

For me, narrative horror can extend into other areas, specifically the constant narrating done to ‘tell and tell’ something (of which, like most writers, I have no doubt been culpable myself). My awareness of this notion was probably brought about by a passage from Marías’ early novel The Dark Back of Time, which he begins with the words: “I believe I’ve still never mistaken fiction for reality, though I have mixed them together more than once, as everyone does, not only novelists or writers but everyone who has recounted anything since the time we know began, and no one in that known time has done anything but tell and tell, or prepare and ponder a tale, or plot one.” This passage inspired the rant that follows its citation in my memoir, The Vagabond’s Breakfast, when I wrote:

“This eternal recounting, this need to tell and tell, is there not something appalling about it – and not only in the sense of whether or not we consciously or intentionally mix reality and fiction? Are there not times when we wish the whole cycle of telling and recounting and explaining and narrating would simply stop – if only for a week, or a day; if only for an hour? The incessant recapitulation and summary and anecdotage and repetition of things said by oneself, by others, to others, in the name of others; the chatter and the news-bearing and the imparting of knowledge and misinformation and the banter and explication and the never ending, all-consuming barrage of blithering fatuity that pounds us from the radio, from the television, from the internet, the unceasing need to tell and make known? And whenever we recount, we inevitably embroider, invent, cast aspersion, throw doubt upon, question, examine, offer for consideration, include or discard motive, analyze, assert, make reference to, exonerate, implicate, align with, dissociate from, deconstruct, reconfigure, tell tales on, accuse, slander or lie.”

We are forever subject — or victim — of the stories we tell about ourselves. All the more reason to remain silent, keep schtum, never breathing a word to anyone about it, that thing that happened and which no one else knows about, but which keeps returning to you in the dead of night . . .

I will leave the last words on narrative horror to Marías, from Fever and Spear, the first book in his trilogy, Your Face Tomorrow, superbly translated by Margaret Jull Costa.

“Narrative horror, disgust. That’s what drives him mad, I’m sure of it, what obsesses him. I’ve known other people with the same aversion, or awareness, and they weren’t even famous, fame is not a deciding factor, there are many individuals who experience their life as if it were the material of some detailed report, and they inhabit that life pending its hypothetical or future plot. They don’t give it much thought, it’s just a way of experiencing things, companionable, in a way, as if there were always spectators or permanent witnesses, even of their most trivial goings-on and in the dullest of times. Perhaps it’s a substitute for the old idea of the omnipresence of God, who saw every second of each of our lives, it was very flattering in a way, very comforting despite the implicit threat and punishment, and three or four generations aren’t enough for Man to accept that his gruelling existence goes on without anyone ever observing or watching it, without anyone judging it or disapproving of it. And in truth there is always someone: a listener, a reader, a spectator, a witness, who can also double up as simultaneous narrator and actor: the individuals tell their stories to themselves, to each his own, they are the ones who peer in and look at and notice things on a daily basis, from the outside in a way; or, rather, from a false outside, from a generalised narcissism, sometimes known as “consciousness”. That’s why so few people can withstand mockery, humiliation, ridicule, the rush of blood to the face, a snub, that least of all … I’ve known men like that, men who were nobody yet who had that same immense fear of their own history, of what might be told and what, therefore, they might tell too. Of their blotted, ugly history. But, I insist, the determining factor always comes from outside, from something external: all this has little to do with shame, regret, remorse, self-hatred although these might make a fleeting appearance at some point. These individuals only feel obliged to give a true account of their acts or omissions, good or bad, brave, contemptible, cowardly or generous, if other people (the majority, that is) know about them, and those acts or omissions are thus encorporated into what is known about them, that is, into their official portraits. It isn’t really a matter of conscience, but of performance, of mirrors. One can easily cast doubt on what is reflected in mirrors, and believe that it was all illusory, wrap it up in a mist of diffuse or faulty memory and decide finally that it didn’t happen and that there is no memory of it, because there is no memory of what did not take place. Then it will no longer torment them: some people have an extraordinary ability to convince themselves that what happened didn’t happen and what didn’t exist did.”

The problem of who you were

Continuing my series of Walks in the Black Mountains. Content warning: alongside description of the actual walks, these extracts also contain my thoughts about writing as well as an amateur’s excursions into the study of consciousness, philosophy of mind and other ontological concerns.

On a Sunday in April, on which, for once, very little rain is forecast, I climb from Capel y Ffin to the Ffawyddog. When I reach the Blacksmith’s Anvil, I rest and eat a breakfast of two small bananas. Now that I am stationary, a hiker, of whom I have been dimly conscious at my rear for a while, catches up. At first I think this will be a repeat of my last walk in these parts, and half expect to see the man from Capel y Ffin, but it is not, although he bears a certain fleeting similarity to that person. He greets me with a comment about the weather having turned out fine, which it has, after a fashion, though it is cold for April, and I am wearing layers, a woollen hat and gloves. The Blacksmith’s Anvil grants a wide-angle view of the moorland before me, and the familiar sight, nestled within sloping hillsides, of the Grwyne Fawr reservoir.

I set off along the narrow gravel path that now defines the crest of the Ffawyddog, turning off at a diagonal (10 o’clock) to the left to pursue the boggy track down towards the reservoir. Near the dam lies the sad, excavated remains of a young pony, a common enough sight hereabouts.

Following the stony banks of the reservoir (the water level is low, which casts into doubt the enormous amount of rainfall we have received these past eight months) I encounter two men in baseball caps, fishing, casting out into the placid deeps. When he sees me, one of them waves in a cheery fashion. There is no evidence of any catch, they don’t even have bags in which to carry fish, no gear, nothing. How on earth did they get here? It occurs to me that they are the ghosts of lost fishermen, or visitors from another world. I dismiss the thought, but not without some resistance.

So I continue the gentle climb upstream towards the source, and there are no more people on this lonely, lovely stretch of the Grwyne Fawr, and I stop to eat my sandwich near the spot where two summers ago I ruminated on the meaning of Providence, and thence (pursuing the analogy of the Black Mountain massif as a hand) to the heel of the palm, more specifically Pen Rhos Dirion, and it is a short walk to the Trig point, at which I arrive precisely as do three middle aged hikers, two male, one female, one of whom, a bulky man with a Midlands accent, has an irritatingly loud voice, a forceful and insistent bellow (why does he need to shout as he walks along these hill tracks, attuned almost exclusively to scattered birdsong, the whistling of the wind and near-silence; why must he shout so? Why does he believe his voice is so worth listening to?) And I hasten my steps, break into a loping canter as I descend the slope towards Rhiw y Fan, and when I turn south-east, following the nascent stream called Nant Bwch, I am relieved that the loudmouth and his companions do not follow.

A solitary red kite circles, guardian at the portal of this narrow valley. With the familiar descent, and the comfort it brings you now that you are alone again, apart from the pipit and the chiffchaff and some other bird you cannot name, you return once more (almost in spite of yourself) to the perennial questions of who you are (or who you were) and what you are doing, especially with regard to what you write, and remember that the writer who has given you most pause for thought on this subject in recent weeks is M. John Harrison, who begins his ‘anti-memoir’, Wish I was here, with these words:

‘When I was younger I thought writing should be about the struggle with what you are. Now I think it’s the struggle to find out who you were.’ His use of the past tense is telling.

Harrison talks a fair bit about the notebook, the writer’s journal, and its function. He makes the astute claim that as a means of recording events, keeping a notebook doesn’t really help (‘writing things down helps less to close that distance than you’d think’) — while conceding that ‘notes make good source material, and when you keep notebooks they eventually begin to suggest something. About what, is not clear. But something, about something.’

I like his vagueness, and at the same time, vaguely distrust it.

As an adolescent, like Harrison, I had nothing set in place, no strategy for achieving adulthood. I suspect that some of my contemporaries had; at least a few of them had absorbed or internalised what was expected of them, but I did not. It was a condition that pursued me long into adulthood itself, exacerbated no doubt by my extravagant intake of alcohol and psychotropic drugs, which, somewhat ironically, I perceived as means of achieving greater self-knowledge, or even as aids on a spiritual quest of sorts. They were not, except as a means of learning that sobriety would serve me better. I would say I did not have a clear, or even any idea of who I was until my own children were born, or shortly afterwards.

Harrison, in his book, returns many times to the notion of his own identity, when he writes of his seventeen-year-old self: ‘I was dying to be someone but I didn’t know how’.

(These are perfectly reasonable thoughts to be having at seventeen, but at 37, or, God forbid, 67? You discover, however, that such thoughts are nor unusual, at any time of life. Some of us are permanently and persistently in search of ourselves. Time, or rather age, helps with one thing: accepting that we might not be a single, cohesive story. We might be many stories, some of which contradict or cancel out others, but all of which are valid; all of them constitute an element of the multifaceted and fragmented self.)

Later in the book, Harrison returns to the theme, always in relation to his writing: ‘The problem of writing is always the problem of who you were, always the problem of who to be next. It is a game of catch-up, of understanding that what you’re failing to write could only be written by who you used to be. Who you are now should be writing something else: what, you don’t know until you try.’

Well, that rings a bell, and for me it resonates with the notion of always starting out, always just beginning, everything feeling new, about which I might, if I were minded to, quote Saul Bellow, who wrote “I have the persistent sensation, in my life . . . that I am just beginning.” This side of things, the ‘feeling new’ side, is, more than anything else, what keeps us going as writers. It is also a feature of certain meditation practices; that one is only ever setting out from the present moment. That there is, in a certain sense, no other time than the present.

Do we ever, though, truly inhabit our own skin? Are we not always at a slight remove from ourselves, one way or another? Experiencing the ‘self’, the person that stuff happens to at a slight distance? Isn’t this key to what you are doing as you walk and as you write? (If you have decided these two activities are the things that define you best). Is it not an examination of walking as the thing you do to keep moving, keep going, one step in front of the other, in rhythm with the breath? Left foot, right foot; breathe in, breathe out.

Cerdded in Welsh is to walk. Cerdd is poetry and/or song. You have long held this correspondence in mind, and it is one that seems the key to a kind of understanding. To walk, to breathe, to write, to sing: could there be a sweeter, simpler way of resolving the matter — at least for the present moment — of who or what you are? It is with this thought in mind that I can be free, or at least temporarily less bothered by such concerns as the one posed by Harrison, that ‘the problem of writing is always the problem of who you were’ — because it needn’t be.

This falling away and return is what we are

Over the past couple of years I have been been keeping a record of walks I take in the Black Mountains, some of which have a philosophical or meditative tone to them, others not. I am unsure quite what these pieces intend to be or what purpose they serve, but following a conversation with my pal Bill Herbert on a curiously extended car trip yesterday, I have revisited them and will be posting a selection over the next few weeks: please make of them what you will!

The first is a walk I took last Midwinter’s Eve.

I read in Galen Strawson’s book Things that Bother Me that our thoughts have very little continuity or experiential flow; that is, most of us experience mental activity as a thinking ‘I’ in fits and starts, with little sense of what we might term ‘joined up thinking’. Strawson, who can always be counted on for a good quote, cites the poet Harold Brodkey, who wrote that ‘our sense of presentness usually proceeds in waves, with our minds tumbling off into wandering. Usually, we return and ride the wave and tumble and resume the ride and tumble . . . This falling away and return is what we are . . .’

And this is the way we (well, I for one) think; we are ‘nomads in time’, our sense of a ‘conscious now’ lasts only about three seconds, our thinking a meandering sequence of stops and starts, starts and stops . . . although, as Strawson reminds us, the self can still be experienced as a continuous thing over a period of time that includes a pause or hiatus. I like the idea of a self that drifts in and out of focus. As I walk today, I try for a while to track the stops and starts of consciousness, of my awareness of my self as participant observer in the ongoing drama of the day, and I find that despite my efforts at continuous, uninterrupted thought, I am forever beginning afresh, on a new train of thought, or rather the ‘I’ that constitutes my ‘self’ is always just starting up, starting out, that I am continually taking on a new iteration of the self (if that is what it is) at any given point in time.

I start up the forestry track on the west side of Cwm Grwyne Fechan. The ground is boggy after days, weeks of rain, and when the track ends, I enter the forest itself, the peaks of the tall pines forming a dome above my head like the cupola of a cathedral. Light filters through, reminding me of the way that those high, stained glass windows in such places of worship were designed to enchant the faithful, light being the trope that forms the core of ‘enlightenment’. We sit (or stand) in awe of such light, and the great Gothic cathedrals mimic nature in this way.

And when I climb to the track, the familiar well-trodden path up the hill where we sometimes go mushrooming, leading to Pen Twyn Glas, I disturb a pair of ponies grazing by a hawthorn tree, but after a few minutes they become accustomed to me and return to their nibbling of the grass, and I guess that they too have undergone a hiatus in their consciousness, or their sense of self, if they have one, and I have no reason to think that they do not, but equally I cannot be sure that it is configured in a way that resembles my own; I can only report on what I observe, or rather the moments that I notice the world in the spaces between these stops and starts, this meandering of the vagrant self that seems to be as close as I ever get to a sense of what I am. Nor do I think about the future, except in the vaguest possible way, and that, I will concede, is something that has become easy to avoid, with the years.

Perhaps I used to think about the future when I was young: I honestly cannot remember. I think I lived pretty much in the day during my twenties, without ambition, without long term aims, but with the conviction (borne out by absolutely no effort of will on my own part) that I would one day most likely want to write, if only, as Leonard Cohen sings in ‘Famous Blue Raincoat’, to ‘keep some kind of record.’ What sort of record I only had the vaguest idea at the time. I realise, however, as I walk (and later, as I write this down) that the idea of keeping track of the vagrant mind, of registering the stops and starts of thoughts and ideas and memories and insights is an almost impossible task.

Night is falling, and I have no desire to return to the car. I wander and I muse and I track my musings, vaguely, though with less and less concern or even interest: it is impossible to follow the jumping bean antics of one’s train of thought, pointless to try and track the fugitive self as it careens through thought and images, smashing up against the wall of intellect, or rationality. And so, irrationally, rather than follow the rough track to join with Macnamara’s way, just above the Tal y Maes bridge, I decide to go down to the Grwyne fechan, though I know I will not be able to cross it without wading, the stream will be in full flow with all these winter rains, but never mind, I will face that obstacle when I get there: I want to hear the rush of water and see the moon through the branches of the trees at the river’s edge. It is as if I am drawn by some mysterious force to the water, that I need to cross the river there, rather than upstream, at the Tal-y-maes bridge. And it is only when I approach that I understand a little why that might be. I had almost forgotten, but we used to come here for picnics when my daughters were small; and further back, if I am not mistaken, I believe I came here myself as a child for a picnic with my parents, but I cannot be sure; it may be a case of me confusing my own childhood with the childhood of my children. In any case, once I have navigated the boggy ground near the river, I seek out a suitable place to cross. There is not one, of course, as I knew there wouldn’t be.

So I look instead for a crossing point that will soak me only to the shins, and step straight into the stream. Five or six steps and it is done. I climb onto the far bank and my boots are drenched. As the water filters through and soaks my socks and feet, I feel a curious release. I needed to cross the stream, though God knows why. The ascent on this bank is steep and covered in bracken. A fence topped with barbed wire needs traversing to reach the lower field, below Tal-y-maes farm. I clamber up to the path, disturbing a straggle of sheep on my way. They regard me with surprise, a human emerging from the wrong direction. This small gesture, crossing the stream for no reason other than because I wanted to grants me a curious and childish delight. As I walk the remaining mile back to the car I quicken my pace, as the water slops and squelches in my boots.

Q&A with Gary Raymond

Last month I was interviewed by the excellent Gary Raymond for his BBC Radio Wales Arts Show (listen here) and last week we did a Q&A in anticipation of our chat at the Abergavenny Writing Festival tomorrow. For more on Gary’s writing, please check out his Substack publication, Blue, Red and Grey.

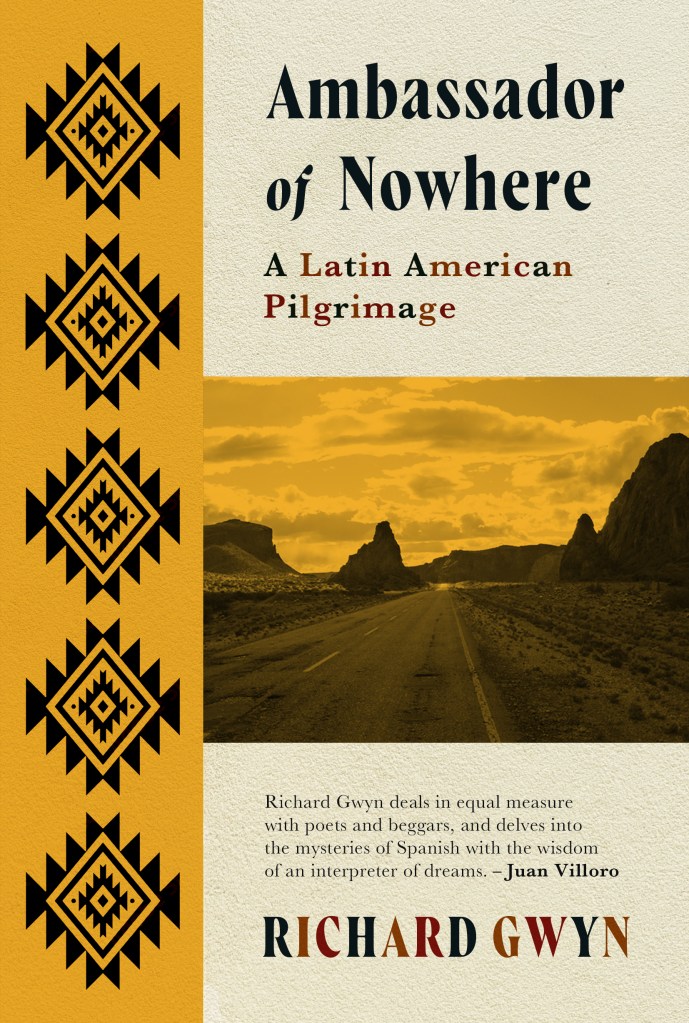

Richard Gwyn’s latest book is a book about the writing of a book, or rather a book about the research for that book, the award-winning The Other Tiger: Recent Poetry from Latin America (which incidentally, was my Welsh book of the year in 2016). Ambassador of Nowhere is a wild and searching ride through several Latin American countries, an in-depth look at cultures and literary movements, as well as political backdrops, full of drinking, poets, and death. What more could you ask for?

I had Richard on the Radio Wales Arts Show a few weeks back to talk about the book, but fortunately, the ever-truncated opportunities for discussion natural to the radio format will be widened on April 19th, as I get to talk to Richard at greater length at the Abergavenny Writing Festival. Details can be found here.

In the meantime, Richard has agreed to engage with my writers’ QnA.

Where are you from and how does it influence your work?

I grew up in Crickhowell and the landscape of the Black Mountains still holds an almost mystical fascination for me. That is my Cynefin, to which I belong and will always return. It’s also near the border, and borders have been a zone of interest to me throughout my life (I once swam across the Evros, the river that forms the border between Turkey and Greece, because my friend and travelling companion, an ‘illegal’ north African migrant, didn’t have papers). On the other hand (and there is always another hand) I am a committed European and internationalist and while I support Welsh independence, I detest provincial or parochial thinking.

Where are you while you answer these questions, and what can you see when you look up from the page/screen?

I am in my attic in Grangetown, Cardiff, with a vista from the loft window of three gigantic tower blocks emerging on the other side of the Taff that will soon dwarf all around them, and block the morning sun from view. Right now my attic space is covered with boxes of books, pots and pans, camping gear, kids’ clothes, a menagerie of cuddly toys, the debris of 30 years living and raising a family in this house. My wife and I are in the process of selling up and moving home, closer to my place of origin (see Q. 1)

What motivates you to create?

No idea, but I can’t imagine not doing it. I like the way that Lydia Davis puts it, when she says that travel, writing and translation are all inextricably linked. That works for me.

What are you currently working on?

I have recently finished a book about the Welsh landscape artist James Dickson Innes (1887-1914) and am now working on a book of perambulations around the Black Mountains (see Q.1)

Writers are always a couple of years ahead of their readers, so a book like Ambassador of Nowhere, which has just been published, was actually finished in 2022. Sometimes it is an effort to remember who you were (or who you thought you were) when you wrote the book that for everyone else is your latest thing.

When do you work?

Very early morning, and for as long as I feel like it — usually no more than three or four hours. It’s a habit I got into when I had a full time job and it works for me.

How important is collaboration to you?

Since I also work as a translator (from Spanish) collaboration is a constant. When I am working on my own stuff, I am accompanied always by my double, or doppelgänger.

Who has had the biggest impact on your work?

As a teenager I was a fanatical reader of the Russian classics (in translation) but probably the turning point came when I discovered the Argentine Jorge Luis Borges as an 18 year old, followed closely by the Italian fabulist Italo Calvino. I have always read widely in other literatures, and having lived in both Greece and Spain for long periods I was influenced in turn by the modern Greek poets, Cavafy, Seferis and Ritsos — and later by a raft of Spanish-language novelists and poets, many of them Latin Americans. I would count Montaigne as an abiding influence, and also perhaps Joan Didion and John Berger. I like to think that the books we haven’t read are always there for us, like an invisible thread leading to places we might one day visit. Reading remains one of life’s great pleasures. But it needs to remain a pleasure, rather than a duty.

How would you describe your oeuvre?

No doubt living in other countries for much of my twenties and thirties set me at a distance from many Welsh authors. I think that has definitely left a mark on the way I regard both my writing and my native country. Since I seem to be writing more about Wales these days, I am curious to see how this will pan out. Ever since reading Raymond Williams’ uncompleted Black Mountains trilogy, I always wanted to complete one of my own. Just to make things difficult for myself, I now envisage my 2019 novel, The Blue Tent, set in the Ewyas valley, as the middle part of that trilogy, rather than the first, as I originally thought, so I now have to write a prequel and a sequel. But I have a pretty good idea of what they are about.

What was the first book you remember reading?

In its entirety? Five go off to Camp, by Enid Blyton. I was maybe six years old.

What was the last book you read?

Wish I was here, a memoir by M. John Harrison. I’m still reading it, and am yet to make up my mind about it. It’s the kind of book that needs time to settle.

Is there a painting/sculpture you struggle to turn away from?

The one on our living room wall. It’s by the Catalan artist Lluis Peñaranda, a dear friend, who died in 2010, far too early. It shows four figures carrying a huge fish.

Who is the musical artist you know you can always return to?

JS Bach and Leonard Cohen.

During the working process of your last work, in those quiet moments, who was closest to your thoughts?

James Dickson Innes. Who is the book’s subject, fortunately.

Do you believe in God?

After a fashion.

Do you believe in the power of art to change society?

No. Or rather, I believe in the power of art to shape ideas, and therefore, to a limited degree, influence trends within society. But fascistic, retrogressive thinking is far more likely to prevail, because most people seem to prefer the certainties of bigotry and prejudice that attach to such a mindset: hence Brexit, hence Trump. I don’t believe in the idea of progress, certainly not in terms of humankind’s capacity for ignorance and cruelty.

Which artist working in your area, alive and working today, do you most admire and why?

If you had asked me this a couple of years ago I would have said the Spanish novelist Javier Marías, but he died in 2022, following complications from Covid. Apart from being an extraordinarily incisive writer (who saw the novelist’s craft as akin to that of the spy) he was also a dedicated enemy of hypocrisy and bullshit. He spent a lifetime pissing people off, which is almost always admirable.

But since Marías doesn’t count, I will go for the Mexican writer Juan Villoro. He is not widely read over here but is considered a major figure in Latin America. I’d especially recommend his novel The Reef, and his astonishing book about Mexico City, Horizontal Vertigo. He has spoken out bravely against the persecution of journalists in a country ravaged by criminal cartels and political and police corruption. His scope and vision are extraordinary and he has also played a significant but discreet role in movements for social justice (his father, Luis Villoro, was an influential figure behind the Zapatista movement of the 1990s).

What is your relationship with social media?

One of dread. I find it useful, up to a point, but am terrified of my own potential for time-wasting.

What has been/is your greatest challenge as an artist?

Getting and staying sober (see next question)

Do you have any words of advice for your younger self?

For much of my earlier life I had serious addiction issues, and although I was constantly filling out notebooks, I wrote nothing of any consequence, so the first thing I’d advise myself would be not to drink quite so much. Since that advice would obviously go unheeded, I’d suggest meditation and a long stretch of solitude on a remote island, preferably uninhabited.

What does the future hold for you?

I am no longer young (or anything near it) so will most likely miss the full consequences of climate catastrophe. But each of us will, necessarily, find our own ways of coming to terms with that, and in the meantime, I have a few more things I’d like to write, and a few long walks to do, alone and in company.

Ambassador of Nowhere is out now.

Blue, Red and Grey is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Gary Raymond is a novelist, author, playwright, critic, and broadcaster. In 2012, he co-founded Wales Arts Review, was its editor for ten years. His latest book, Abandon All Hope: A Personal Journey Through the History of Welsh Literature is available for pre-order and is out in May 2024 with Calon Books.

Ambassador of Nowhere

Thursday March 28th saw the launch of Ambassador of Nowhere. I was interviewed by the astute and genial Jon Gower – who has helped launch three of my books to date – and there were a few questions from the audience. The gist of our chat was reported by Martin Shipton and published in Nation Cymru here.

The book describes many journeys, and was a journey in itself, several years in the making, and I am happy (and relieved) that it is finally out there. A Spanish version is due to be published later this year, by Lom in Chile and Bajolaluna in Argentina, translated by Jorge Fondebrider.

Here is the article I submitted to Nation Cymru on the topic ‘On Being a Writer in Wales’.

The American writer Lydia Davis once wrote that “to translate is also to read, and to translate is to write, as to write is to translate and to read is to translate. So that we may say: To translate is to travel and to travel is to translate.” These words resonate powerfully with me, having recently completed a book about travel and translation. So how does this fit with ‘being a writer in Wales’?

As a Welsh writer, I have written relatively little about my native land. The publisher’s blurb on my first poetry collection, more than thirty years ago, put it this way: ’Some Welsh authors write solely about Wales. Richard Gwyn stands apart from these . . .’ A review of my most recent book of poems, Stowaway: A Levantine Adventure, continues in the same vein: ‘For a book written by a Welshman, published by a Welsh press, supported by the Welsh Books Council and reviewed in Wales Arts Review, it is remarkably reticent about Wales – with, I think, only a single mention of Gwalia to nod to its native land.’

It is strange for me to read this, because even though my books have often been set far from Wales — my first novel was set in Barcelona, the second in Crete, both places in which I lived for long stretches during my twenties — I feel deeply attached to the red loam of my native patch, have lived for the past 33 years in Cardiff and yet, at the same time, I don’t really think of myself as belonging anywhere. A paradox, I know, but one that I share with the Scottish poet and translator (from Spanish, like myself) Alastair Reid, who claimed that the ideal state for a writer might be that of a ‘foreigner’, someone who has no proper home, no secret landscape claiming them, no roots tugging at them. Such a person is, if you like, properly lost, and so in a position to rediscover the world, from outside in. Reid believes that if they are lucky, such adventurers might “smuggle back occasional undaunted notes, like messages in a bottle, or glimmers from the other side of the mirror.” Sometimes I feel as though I have always been a foreigner.

Only in my third novel, The Blue Tent, did I ‘come home’. I always suspected I would, but it just took time. And The Blue Tent will almost certainly not be the last of my books to engage with Wales, or rather, the small portion of it that I recognise as unmistakably my own, the Bannau Brycheiniog, or more specifically the Mynyddoedd du, or Black Mountains, that mysterious massif in the shape of a hand, which forms a landscape, or a dreamscape, that for me bears all the characteristics of a recurring obsession.

Which brings me, in a roundabout way to my latest book, Ambassador of Nowhere: A Latin American Pilgrimage. This is a story that deals with travel to distant places — Nicaragua, Mexico, Argentina, Chile and Colombia — and is deeply in thrall to the notion of ‘being a foreigner’, although I do end up back in Wales towards the end of the book, chasing memories of my father, who was, for most of his working life a GP in rural Powys. I had not intended him to figure in the book, but he died as I was nearing its end, and I couldn’t keep him out.

I have always loved maps, and in my late teens I stuck a map of South America on my bedroom wall. Convinced that I had a special affinity with that continent, the map proved strangely prophetic, but it took me three decades to put my travel plans into action. The ‘Ambassador’ of the title is flagrantly deceptive. In 2014, I spent a year as a ‘Creative Wales Ambassador’ (a term chosen by the Arts Council of Wales, not me) and since I had been commissioned to complete an anthology of Latin American poetry in translation, published as The Other Tiger in 2016, it seemed like a good idea to chronicle my journeys across that continent in search of its poets and poetry.

It was unfortunate, to say the least, that I ended up in conversation with a small town police sergeant in Colombia, who on being told I was from Wales, informed me that no such place existed, and that I must therefore be the Ambassador of Nowhere. Ironically, that town on the Magdalena River, which has the unlikely name of Mompox, is itself remembered in words uttered by General Bolivar, the Liberator, who (according to Gabriel García Márquez) claimed that “Mompox does not exist. At times we dream of her, but she does not exist.” In this way I was caught in a web of illusion, or of dreams: a policeman from a town that may not exist accusing me of coming from a non-existent country. Eduardo the police sergeant and his brother-in-law Washington then took me to the saddest discoteca in the word, where we downed two bottles of fiery aguardiente, while a handful of dancers, all of them middle-aged and half-drunk, circled aimlessly in a moribund chug around the dance floor to the lachrymose accompaniment of a pot-bellied Latin crooner. The policeman never guessed that he had gifted me the title of my book.

Returning to my opening quote from Lydia Davis, I happen to believe that whether or not we write or travel, translation forms a fundamental aspect of who we are, since we are all translators. While early childhood is the acute phase of translation, a period marked by insatiable curiosity and of translating and being translated by others, it seems to me that any writer worth their salt remains curious and continues to translate, because all writing is a form of translation — from silence, or from life itself.

For those who were unable to attend the launch, I will be in conversation with the excellent Gary Raymond at Abergavenny Writing Festival, on April 19th at 15.00. In case you missed it, I was interviewed about the book by Gary for his Radio Wales Arts Show, which can be found on BBC Sounds.

I will also be at Book-ish, Crickhowell, on 7th May at 19.30, in conversation with the super-talented author Nicola Rayner.

Ambassador of Nowhere is published by Seren and can be found at good bookshops. It is the companion piece, or secret double, of my anthology The Other Tiger, also published by Seren.

This is not a border

The Coll de Banyuls, on the edge of the French department of Pyrenées Orientales, offers a convenient path across the border between France and Spain, an alternative to the major highway crossing, fifteen kilometres to the west as the crow flies — but far longer by road — at La Jonquera.

There is no customs post at the Coll de Banyuls, and there was no covered road here until about ten years ago, but the locals knew about it all too well: historically it played an important role in the frontier traffic, especially during the Spanish Civil War, when tens of thousands of refugees crossed over, to be herded into camps along the beaches at Argèles-sur-mer and Saint-Cyprien. Shortly afterwards, in the years that followed the Civil War, many other refugees crossed, in the opposite direction, fleeing Nazi-occupied Europe. They were assisted at every stage by the local Maquis and guides who risked their lives to take small groups of migrants across the mountains, many of them already exhausted by their flight and terrified of capture. The most famous of these refugees was the German philosopher Walter Benjamin, who crossed a short distance to the east of here, at Portbou. In the valley below, a few kilometres inland from Banyuls, stands a memorial to the brave villagers who guided their charges across the mountains.

Shortly after the Coronavirus pandemic broke out, the border was closed to traffic. The French police set up a barricade consisting of four huge boulders, preventing vehicles carrying Covid-infected passengers from one country to the other. Curiously, this narrative changed the following year, and the closure of the road was justified as an attempt to prevent the passage, as a local French newspaper claimed, of ‘illegal immigrants and drug smugglers.’ Why such felons should pass this way, rather than via the main crossing at La Jonquera, where there is no passport control, or by any of the other minor crossings for that matter, remains a mystery.

In the nearby villages on the Spanish side, fuelled by the autocratic decision of the French police to close the border, the rumour started circulating that ‘terrorists’ had been using the pass, a weird skewing of the truth that managed to convolute two variations on the notion of the ‘other’, blending fear of Coronavirus with fear of the masked bomber. In these paranoid times, however, such confabulations should come as no surprise. Walking near the pass in the late spring of 2022, I noticed a couple of camouflaged SUV’s, hidden behind a clutch of bushes and quite invisible from the road on the Spanish side. The foremost of the vehicles sported a banner above the windscreen that read ‘FORCE VIGIPIRATE’. A quartet of heavily-armed soldiers stood at their ease, chatting. One of them greeted me with a cheery ‘Bonjour’ as though his presence there were a routine matter, and he and his colleagues were here simply to enjoy the view. I continued on my way, and onto French terrain, along a trail that hugged the flank of the mountain I had just descended.