To be always the same person

I have driven past Bryn Arw countless times on my way to the Vale of Ewyas and Llantony, but only became aware of it as a separate entity about three years ago when a graffito appeared on the hillside, carved, as it were, into the ferns: ‘Daw eto ddail ar fryn’ — which means ‘There will be leaves on the hill again.’ The line is a play on words, intentionally mis-quoting a line of poetry popular across Wales during lockdown – ‘Daw eto haul ar fryn’, meaning ‘There will be sunshine on the hill again’. The words were carved into the hillside by a local charity called ‘STUMP UP FOR TREES’ / ‘CEINIOGI’R COED’ who are intent on an ambitious replanting programme that will help improve biodiversity in the area. They hope to plant one million trees on hillsides and marginal agricultural land across the area.

I walked Bryn Arw for the very first time last Christmas Eve. It turned out to be the windiest of days, and I set out along with a few family members and a borrowed dog, a scruffy but amiable mutt named Bluey. We all needed to get out of the house before Christmas indolence melted our brains. First we hugged the lower reaches of Pen-y-fal, or the Sugar Loaf, before turning east and climbing to the long ridge of Bryn Arw. Here we were so buffeted by the southwesterly wind that it felt almost as if the next gust might lift our bodies from the ground and drive us high into the air, depositing somewhere in the green fields of Herefordshire.

The strange thing about walking Bryn Arw is that, never having walked it before in this lifetime, I have no memories of it, unlike almost all the other walks I do around these hills. And that, I realise before we are half way up, makes a difference. When I am walking around Llantony or Capel or Ffin or the Grwyne fechan valley, I am brushing up against the countless versions of myself left hanging around from previous excursions. At times a sense memory washes over me of having been present at this spot many times before, and that makes a difference. How does it make a difference? How does it ‘feel different’ on Bryn Arw to being in a place you know intimately? ‘The difference is that on Bryn Arw I am, after a fashion, a new version of myself and have no comparators. I am aware of being in a new place with distinct perspectives and views of the hills around about. For example, looking out towards Partrishow hill and Crug Mawr behind it, I am looking at places I know well from a new angle, and that seems to correlate precisely — albeit in a rather minor way — with occupying a distinct version of myself from the one on previous visits.

In his Meditations, Marcus Aurelius considers it a virtue “to be always the same man” , which suggests to me as much a Roman adherence to manly qualities as an insistence on a continuity of self. But in order to be always the same person one needs to be in possession of a sense of self in the first place, one that is continuous over time. However, it seems clear to me when considering an event or series of occurrences in my past, that the ‘I’ that is doing the remembering in the present is not the same ‘I’ that is being remembered. Or, to put it slightly differently — and following on from an argument famously put forward by Galen Strawson — they might have happened to Richard Gwyn but they didn’t happen to me, as I am in this moment.

This perception of ‘myself’ is further complicated by the fact that at key, or seemingly pivotal points in my life I have always experienced a strong sensation that I am detached from myself in a significant way, as though looking on from a slight distance as ‘I’ — the physical entity I recognise as RG — undergoes stuff happening. Thus I am these two distinct entities — the experiencing self and the detached disembodied thing that is also ‘I’ but somehow independent, ‘above’ or ‘outside’ of me, and yet simultaneously the most intrinsic, innate version of ‘me’ (at least as far as I can tell: it is quite possible that within the lifeworld of that more intimate, innate ‘me’ lurks yet another more intrinsic version, and so on, peeling away the versions like onion skins). When looking in the mirror, for example, the physical form that looks back at me — RG, to others — is somehow ‘not me’, but the form or person that I temporarily inhabit. This corresponds with the idea that sometimes I am observing myself thinking, and even observing myself as if from outside myself, as described at one or two points in these posts. I imagine this is fairly common, but I don’t know or whether its increasing frequency in my life might be accounted for by my historical consumption of mind-altering drugs, or some other cause, such as the recurrent insomnia from which I have suffered for much of my life. Perhaps this is significant. Insomnia brings about a sense of detachment, an impression that nothing is quite real. I was reminded of this, coincidentally, by watching the movie Fight Club the other night, when the narrator comes out with the line: ‘With insomnia nothing is real. Everything is far away. Everything is a copy of a copy of a copy.’

I’m sure we have all had similar moments, when our sense of detachment from the body — or even the ‘person’ inhabiting that body — is more pronounced, even to the point of feelings strangers to ourselves. On a certain level this happens to us incrementally as we get older.

And I am wondering, as we prepare to move home: how does being in a new place affect not only awareness of your surroundings but also, correspondingly, self-awareness? We often slip into complacency, or a kind of non-seeing when in familiar places, but in a new place — as a tourist, or walking in an unfamiliar landscape — we tend to be more alert, taking in details of our surroundings with a heightened intensity. In some ways, this perception of familiarity versus strangeness carries over into our perception of ourselves within those spaces also. It is as though we harbour the ability to be more aware, or more mindful when the circumstances demand it, or else when we choose to be. And this is something that is useful for writers. When I taught writing classes I would sometimes send students out to write at a cafe in Cardiff market or in one of the arcades, and imagine that they were seeing the scene before them for the first time — as a stranger or a ‘foreigner’, in the extreme sense of the world (someone with no bonds of belonging, someone truly lost). To write from the perspective of one who sees everything for the first time.

Curiously — as though this were a recurring obsession — when I was nineteen, I wrote a short story about such a person, a man who each night forgets everything about himself, his life and his surroundings. But I lost the story or else threw it out. It turned out there was not a lot to say about this man other than that he forgot everything. As such, I was pulling the rug of storytelling from under the feet of my protagonist before I started, since all storytelling resides in memory.

The last Welsh speakers of the Black Mountains

On my most recent excursion to the hills I have no new agenda following on from the ‘how long can you stay focused on anything at all’ theme, which, to be honest, turned out to be something of a red herring on the last two walks. I learned that I cannot focus on anything for very long at all and merely confirmed what I already suspected: my monkey mind settles with great difficulty. So I gave myself a break on this walk, and decided I would simply take in the landscape, breathe deeply, and put one step in front of the other. This proved to be a successful strategy (i.e. it was not a strategy at all, but simply a walk).

I set out early for the Grwyne Fechan valley, park the car near the bridge below Neuadd fawr farm and start walking, with nothing much on my mind, intent on following the forest track that continues along the western slope of Cwm Grwyne Fechan; then I will take Macnamara’s Way up to Mynydd Lleisiau, and on to Pen Twyn Glas, before descending back to my starting place, past the abandoned quarries above Cwm Banw.

The track that emerges out of Park Wood, above Darren farm, on the west bank of the Grwyne Fechan, is extremely boggy, even now, in May, with the effect of walking through deep sand. It is wearying, and you long for a hard surface; dry soil or gravel. It comes as a relief then, to reach Macnamara’s Way.

The ascent is not arduous, and by the time you arrive at the summit of Mynydd Lleisiau you are quite calm: the sun has appeared, and the way ahead is clear. At this point you observe, jogging towards you, the first human of the day, a youngish man in a safari hat and shorts, with a dog on a leash running somewhat reluctantly (or so it appears) alongside him. But what draws your attention is that the dog is carrying saddle bags. You are surprised by your own reaction, which is one of muted anger towards the man. You can understand, just about, why he might prefer to run along mountain trails rather than walk, but why must he inflict this passion on his poor dog? And why should the dog be forced to carry a backpack, as if it were a mule? I can feel my mood thickening as the man approaches, and calls out to me, without easing his pace, Good morning, how are we doing? Well, first of all, he clearly doesn’t require an answer, as he doesn’t stop, so why does he pose the question? And why the use of first person plural, the way certain people speak to invalids or persons of feeble mind? I understand that the question is rhetorical rather than functional, much like the local use of ‘orright’? But he is most definitely not a local and doesn’t pose the question as if it were rhetorical and nor does he stop to receive an answer. I am taken aback, put off my stride. I know I shouldn’t be affected this way, but I am. More so, in fact, when a hundred paces behind him, over the crest of a slight dip, appears his weary-looking partner, blond hair tied back and bunched in a tight knot, grimacing a little with the strain of keeping up, but stoical. She manages a greeting also (but without posing any questions, rhetorical or otherwise). I am relieved to observe that she hasn’t been obliged to carry a rucksack, that she is just allowed to plod along behind the Great Adventurer, in her tight fitting black joggers and expensive looking black top. I feel for her.

I stop off to eat my sandwich next to the boundary stones on the knoll near (but not on) the summit of Pen Twyn Glas, set there by the widow Mary Macnamara and Sir J. Bailey Bart, whose estates met at this point in the early to mid 19th Century. (See Graeme Adkin’s blog, ‘Black Mountains Walking’ at https://www.blackmountainswalking.co.uk/the-black-mountains-magic where he cites John Barber writing in The Beacon)

The descent from Pen Twyn Glas in the late morning sun is breathtaking, and there is the sublime joy of looking down over Cwm Banw to the right, and ahead to Pen y Fal. Quite why Cwm Banw and the Grwyne Fechan valley affect me in this way I cannot say, but I have an allegiance to the zone that feels arcane, ancestral, a thing of the blood. It is a passion I share with at least a few others. T.J. Morgan, a young University lecturer in Welsh, recalled his first visit to the Grwyne Fechan valley in January 1939, after a heavy snowfall, in tones of mystical reverence. The visit is recounted by his son, Prys Morgan, in the annual journal Brycheiniog and can be found in the back issues section, Volume 51 (2020) on pages 136-41.

‘He was immediately overwhelmed by the magical silence and beauty of Grwyne Fechan, all glittering in midday sunshine, and was humbled by a sense of awe. For the only time in his life, he felt part of something cosmic, filled with utter purity, a feeling of being part of a cosmos that was just being created and before the arrival of life’.

The purpose of Morgan’s trip to the valley was to track down and interview the last Welsh speakers. As his son writes:

‘There were five people in Grwyne Fechan who spoke Welsh, all over eighty, but none had spoken it to anybody else for many decades. The old man (John Williams y Felin) was astonished to hear Welsh from the lips of a young man; the language being something already belonging to the past.’

In the mid-19th century, we learn, all the families in Grwyne Fechan had been Welsh-speaking, apart from one family of Scots. Morgan managed to make a few recordings (notably of John Williams y Felin) but his plan to record all the octogenarians in the valley in 1939 was laid to rest by the outbreak of World War Two. The military commandeered all the BBC cables and private vehicles were to be taken off the roads. By the time the war had ended, six years later, all the elderly people in the Grwyne Fechan valley were dead.

Many of us have wondered what kind of Welsh was spoken by those last users of the language in the Black Mountains. The musician and writer Tom Morys, and his band Bob Delyn a’r Ebillion, have made poignant use of Morgan’s recording with their ballad Cân John Williams, which opens with the voice of Williams, as recorded in 1939. In a nice touch, Morys dedicated his song to the children at the new Welsh-medium school in Abergavenny, Ysgol Gymraeg Y Fenni. The voice echoes huskily across the chasm of the years, eliciting the sound of a remote rural community lost to time, but not to the imagination.

The problem of who you were

Continuing my series of Walks in the Black Mountains. Content warning: alongside description of the actual walks, these extracts also contain my thoughts about writing as well as an amateur’s excursions into the study of consciousness, philosophy of mind and other ontological concerns.

On a Sunday in April, on which, for once, very little rain is forecast, I climb from Capel y Ffin to the Ffawyddog. When I reach the Blacksmith’s Anvil, I rest and eat a breakfast of two small bananas. Now that I am stationary, a hiker, of whom I have been dimly conscious at my rear for a while, catches up. At first I think this will be a repeat of my last walk in these parts, and half expect to see the man from Capel y Ffin, but it is not, although he bears a certain fleeting similarity to that person. He greets me with a comment about the weather having turned out fine, which it has, after a fashion, though it is cold for April, and I am wearing layers, a woollen hat and gloves. The Blacksmith’s Anvil grants a wide-angle view of the moorland before me, and the familiar sight, nestled within sloping hillsides, of the Grwyne Fawr reservoir.

I set off along the narrow gravel path that now defines the crest of the Ffawyddog, turning off at a diagonal (10 o’clock) to the left to pursue the boggy track down towards the reservoir. Near the dam lies the sad, excavated remains of a young pony, a common enough sight hereabouts.

Following the stony banks of the reservoir (the water level is low, which casts into doubt the enormous amount of rainfall we have received these past eight months) I encounter two men in baseball caps, fishing, casting out into the placid deeps. When he sees me, one of them waves in a cheery fashion. There is no evidence of any catch, they don’t even have bags in which to carry fish, no gear, nothing. How on earth did they get here? It occurs to me that they are the ghosts of lost fishermen, or visitors from another world. I dismiss the thought, but not without some resistance.

So I continue the gentle climb upstream towards the source, and there are no more people on this lonely, lovely stretch of the Grwyne Fawr, and I stop to eat my sandwich near the spot where two summers ago I ruminated on the meaning of Providence, and thence (pursuing the analogy of the Black Mountain massif as a hand) to the heel of the palm, more specifically Pen Rhos Dirion, and it is a short walk to the Trig point, at which I arrive precisely as do three middle aged hikers, two male, one female, one of whom, a bulky man with a Midlands accent, has an irritatingly loud voice, a forceful and insistent bellow (why does he need to shout as he walks along these hill tracks, attuned almost exclusively to scattered birdsong, the whistling of the wind and near-silence; why must he shout so? Why does he believe his voice is so worth listening to?) And I hasten my steps, break into a loping canter as I descend the slope towards Rhiw y Fan, and when I turn south-east, following the nascent stream called Nant Bwch, I am relieved that the loudmouth and his companions do not follow.

A solitary red kite circles, guardian at the portal of this narrow valley. With the familiar descent, and the comfort it brings you now that you are alone again, apart from the pipit and the chiffchaff and some other bird you cannot name, you return once more (almost in spite of yourself) to the perennial questions of who you are (or who you were) and what you are doing, especially with regard to what you write, and remember that the writer who has given you most pause for thought on this subject in recent weeks is M. John Harrison, who begins his ‘anti-memoir’, Wish I was here, with these words:

‘When I was younger I thought writing should be about the struggle with what you are. Now I think it’s the struggle to find out who you were.’ His use of the past tense is telling.

Harrison talks a fair bit about the notebook, the writer’s journal, and its function. He makes the astute claim that as a means of recording events, keeping a notebook doesn’t really help (‘writing things down helps less to close that distance than you’d think’) — while conceding that ‘notes make good source material, and when you keep notebooks they eventually begin to suggest something. About what, is not clear. But something, about something.’

I like his vagueness, and at the same time, vaguely distrust it.

As an adolescent, like Harrison, I had nothing set in place, no strategy for achieving adulthood. I suspect that some of my contemporaries had; at least a few of them had absorbed or internalised what was expected of them, but I did not. It was a condition that pursued me long into adulthood itself, exacerbated no doubt by my extravagant intake of alcohol and psychotropic drugs, which, somewhat ironically, I perceived as means of achieving greater self-knowledge, or even as aids on a spiritual quest of sorts. They were not, except as a means of learning that sobriety would serve me better. I would say I did not have a clear, or even any idea of who I was until my own children were born, or shortly afterwards.

Harrison, in his book, returns many times to the notion of his own identity, when he writes of his seventeen-year-old self: ‘I was dying to be someone but I didn’t know how’.

(These are perfectly reasonable thoughts to be having at seventeen, but at 37, or, God forbid, 67? You discover, however, that such thoughts are nor unusual, at any time of life. Some of us are permanently and persistently in search of ourselves. Time, or rather age, helps with one thing: accepting that we might not be a single, cohesive story. We might be many stories, some of which contradict or cancel out others, but all of which are valid; all of them constitute an element of the multifaceted and fragmented self.)

Later in the book, Harrison returns to the theme, always in relation to his writing: ‘The problem of writing is always the problem of who you were, always the problem of who to be next. It is a game of catch-up, of understanding that what you’re failing to write could only be written by who you used to be. Who you are now should be writing something else: what, you don’t know until you try.’

Well, that rings a bell, and for me it resonates with the notion of always starting out, always just beginning, everything feeling new, about which I might, if I were minded to, quote Saul Bellow, who wrote “I have the persistent sensation, in my life . . . that I am just beginning.” This side of things, the ‘feeling new’ side, is, more than anything else, what keeps us going as writers. It is also a feature of certain meditation practices; that one is only ever setting out from the present moment. That there is, in a certain sense, no other time than the present.

Do we ever, though, truly inhabit our own skin? Are we not always at a slight remove from ourselves, one way or another? Experiencing the ‘self’, the person that stuff happens to at a slight distance? Isn’t this key to what you are doing as you walk and as you write? (If you have decided these two activities are the things that define you best). Is it not an examination of walking as the thing you do to keep moving, keep going, one step in front of the other, in rhythm with the breath? Left foot, right foot; breathe in, breathe out.

Cerdded in Welsh is to walk. Cerdd is poetry and/or song. You have long held this correspondence in mind, and it is one that seems the key to a kind of understanding. To walk, to breathe, to write, to sing: could there be a sweeter, simpler way of resolving the matter — at least for the present moment — of who or what you are? It is with this thought in mind that I can be free, or at least temporarily less bothered by such concerns as the one posed by Harrison, that ‘the problem of writing is always the problem of who you were’ — because it needn’t be.

How long can you stay focused on anything at all . . .

I have been wondering about the capacity of the mind to focus on anything for more than a few seconds at a time. A lot has been published on this topic in recent years, especially relating to children’s use of the internet and social media. An article I read somewhere suggested that the maximum attention span is around eleven minutes, but that seems optimistic: when engaged in mindfulness meditation, for example, it can be difficult to maintain focus on one’s breath for more than eleven seconds.

Nevertheless, and despite all evidence to the contrary, I decided one day to try and focus only on my breathing and on taking one step after another, over the course of a twelve mile walk. I would impersonate a being with no mental baggage, with ‘nothing extra’, as Shunryu Suzuki puts it. Despite the fact that I have tried this before, and failed, I want to see whether I can maintain a sustained awareness of myself as only a walking, breathing entity — or at least a being with this intention, which may or may not be the same thing — over the course of the entire walk. I know that I am setting myself up to fail again, but I will do it anyway, just to see . . .

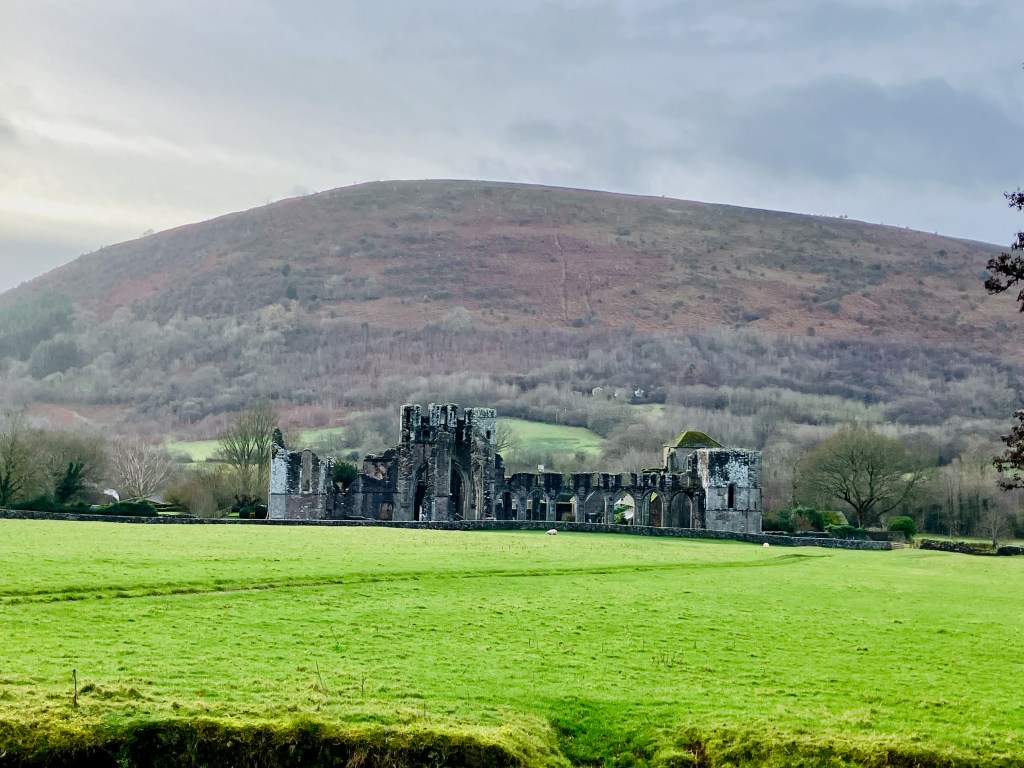

So, on a January morning in 2024 — the first day of the new year on which it is not pelting with rain — I set off on a circular walk from Llanthony Priory. My plan is to climb up to the Offa’s Dyke trail, follow it for a couple of kilometres, turn west down the steep track towards The Vision farm, take a right along the lane to Capel y Ffin, climb to the Ffawyddog (which separates this valley from Cwm Gwyne Fawr) and follow the ridge down to Bal Mawr and thence down Cwm Bwchel, back to Llanthony. Twelve miles, give or take. Six hours including picnic lunch and stops.

Before I get to the first turning, on the relatively flat stretch along the Offa’s Dyke path, I am doing pretty well. I am practising in the same way as I meditate, by breathing and focusing on my breath, step after step. I lose myself from time to time, of course, the monkey mind turns somersaults in the usual way, and I slip into the internal monologue occasionally, but I am doing OK, although, of course, I am not ‘getting anywhere’. Nor do I want to. There is, needless to say, nowhere particular to get to, except one step after another, one breath at a time.

But the fact is, however much I try to convince myself otherwise, I am crap at this. My mind is playing jumping jacks. Within minutes I am all over the place. I have no sense of being a consistent individual, a single thinking feeling entity for more than thirty seconds at a time, maximum. The fundamental thing that distinguishes me from the moorland pony with the swollen belly that I pass along the way is that while the pony is no doubt conscious, I am conscious that I am conscious, and I rather doubt that she is. I am conscious that I am conscious, and that is why I am putting myself through this pointless exercise. I’m not saying that the pony, or the walker’s dog that I see approaching on the far horizon is a lesser being, but I am pretty damn sure that neither of them is spending their time worrying about the permutations of their consciousness, or their failure to keep their attention on one thing at a time.

As I walk, I am getting a sense that there are two distinct ways of regarding the self, or one’s own inner personhood. The first type of consciousness is that I am aware of myself as a physical human being, a human being considered as a whole. This is the human being I encounter in the mirror when brushing my teeth or shaving, the one who looks back at me, and whom I dimly recognise as the same human being I have always been, albeit with obvious differences from the person I was, say, forty years ago, and with minor variations from the person I was yesterday. Let’s call this one the outer self.

The other type of self is, in Galen Strawson’s words, an ‘inner mental presence’, one who has the ability to observe and record the antics of the outer self. This ‘inner mental presence’ is the one I am trying to keep track of as I walk, and finding it incredibly difficult to do so. And, as I have (unthinkingly) just written ‘I’, this poses the question of a third participant, the ‘I’ that is monitoring the ‘inner mental presence’ as it, in turn, attempts to stay focused. Does this suggest three constituent parts to my identity? — (i) the physical body striding over the moor, (ii) the inner mental presence experiencing thoughts and feelings, and (iii) the ‘I’ making a note of all this, monitoring the ‘inner mental process’? Or are there more, an infinitely recursive number of selves, each of them monitoring the one within the adjacent ‘layer’ of selfhood? This is precisely the kind of conundrum posed by reading Borges for the first time, or by studying fractals, or taking LSD or magic mushrooms . . . and yet it is a valid mode of thought, because otherwise I would not be thinking it, surely?

Clearly, I have strayed from the original plan to stay focused on nothing but my breath and putting one foot in front of the other (was that the plan?). I now have to contend with the overwhelming issue of multiple selves, and how to select one among many . . .

Perhaps the most striking thing I can say about this inner mental presence is that, at best, one is in a state of constant renewal. As I mentioned in last week’s post, the poet Harold Brodkey says “our sense of presentness usually proceeds in waves, with our minds tumbling off into wandering . . . This falling away and return is what we are.” How true this feels, I think, as I pound the turf, the familiar muddy turf of these red sandstone hills. Despite the permanent feel of the place, and of my place within it, I cannot help but feel that something is always just beginning, and — whatever I am — I am a part of it. And yet, and yet . . . my mind keeps ‘tumbling off into wandering’, an awkward phrase that at once brings to mind the errant perambulations of a lost soul.

I turn off Offa’s Dyke path towards the valley and the descent gets pretty steep, and because of the rain, the track is slippery. As I near the bottom of the hill I look back and see a figure high above me on the same path, silhouetted against the skyline, utterly unmoving. It seems to be the figure of a man. The image reverberates with me in a curious way, almost as though it were lifted from a Caspar David Friedrich painting. It feels somehow prescient, as though this figure were not only observing me, but had also registered me observing him. The irrational thought occurs to me that this figure, this personage, is somehow significant, or will become so. It is one of those moments when you half-grasp a sense of something about to happen imminently, but in only the vaguest way. Half an hour later, at a gate that opens onto a field close to the valley road, the figure on the hill catches up with me. He is about the same age as me; that is, getting on in years. Without necessarily intending it, we fall into conversation. Neither of us, I suspect, is much given to chatting while on a walk: the very reason one does a walk like this is (often) that one wishes to be alone. Also, I sense — correctly, as it turns out — that he, if not exactly in a hurry, has somewhere to get to, which I do not. Not in the short term, anyway.

I see the road — he says, pointing at the lane that runs from Llanthony to Capel y Ffin — has finally been fixed. The stretch he is indicating has been under repair for many years. A sign proclaiming that the road is closed has warned motorists coming down (or up) the valley to that effect almost for as long as I care to remember. Oh good, I reply, adding that I have never taken any notice of the ‘Road Closed’ sign anyway. Ah, so you’re local, then, he retorts, with a lopsided grin. Well, kind of, I say. I grew up nearby but live in Cardiff . . . and you? It transpires he is from Capel itself, but has lived in Abergavenny for many years. It turns out he knew my father. ‘A legend’, he says. I let the comment hang there a while. I’m curious, but I don’t ask. Recognising some kind of kinship, perhaps, we talk about the different valleys of the Black Mountains, and their respective qualities. It turns out his own father had a special affection for the Grwyne fechan valley, as did mine. He enjoyed the quiet there, says the man.

We pass a cottage, once a farm, now a second home, like many other places in the valley. When we were children, the man says, we used to come carol singing here at Christmas — here and the other farms. He sounds happy at the memory rather than sorrowful at the fact that nearly all the farms hereabouts have been bought up by strangers from across the border, people from London and Bristol. But it makes me sad; no, it also makes me angry, but my anger is pointless, and not directed at any particular individuals, just at the disappearance of a way of life, sadness at the death of a small community, fragile as it was.

We approach the Grange, a large house and pony trekking centre, and the man explains that he has arranged to stop off for tea with an elderly relative who lives there. I continue alone, and climb to the Ffawyddog, where I take a break at a rock called the Blacksmith’s Anvil, sit and eat my sandwich, drink tea, and enjoy the view over the moor towards the Grwyne Fawr reservoir.

Within fifteen minutes, the man reappears, climbing the hill behind me. He has caught up with me, as I guessed he would, and stays a while longer, munching on a sandwich of his own. I tell him I wrote a novel set in the valley — The Blue Tent — and he expresses interest, and surprise, because he thought he had read everything published about the place. I tell him I’ll send him a copy, and he scribbles out his address in pencil, on a small notebook he carries with him. The taking of pencil and notebook on a walk in the hills reveals something about a person, I feel. My handwriting has improved since I retired, he comments, with a wan smile, although I have said nothing. I assume, correctly, that he will want to continue on his own, as he is a fast walker — ‘no one keeps up with me except my brother’ — and he needs to be at the Llanthony car park at 4.15 pm for his lift. There’s no way I could keep up with him, although I am no slouch myself. I let him leave, and within a couple of minutes he is almost out of sight. He stops still, briefly, near the rocks at Chwarel y fan, and it is a replay of the first time I saw him, above me on the hillside across the valley, silhouetted again the sky, statuesque, looking about him. And he vanishes into the amber light of the ebbing day.

This falling away and return is what we are

Over the past couple of years I have been been keeping a record of walks I take in the Black Mountains, some of which have a philosophical or meditative tone to them, others not. I am unsure quite what these pieces intend to be or what purpose they serve, but following a conversation with my pal Bill Herbert on a curiously extended car trip yesterday, I have revisited them and will be posting a selection over the next few weeks: please make of them what you will!

The first is a walk I took last Midwinter’s Eve.

I read in Galen Strawson’s book Things that Bother Me that our thoughts have very little continuity or experiential flow; that is, most of us experience mental activity as a thinking ‘I’ in fits and starts, with little sense of what we might term ‘joined up thinking’. Strawson, who can always be counted on for a good quote, cites the poet Harold Brodkey, who wrote that ‘our sense of presentness usually proceeds in waves, with our minds tumbling off into wandering. Usually, we return and ride the wave and tumble and resume the ride and tumble . . . This falling away and return is what we are . . .’

And this is the way we (well, I for one) think; we are ‘nomads in time’, our sense of a ‘conscious now’ lasts only about three seconds, our thinking a meandering sequence of stops and starts, starts and stops . . . although, as Strawson reminds us, the self can still be experienced as a continuous thing over a period of time that includes a pause or hiatus. I like the idea of a self that drifts in and out of focus. As I walk today, I try for a while to track the stops and starts of consciousness, of my awareness of my self as participant observer in the ongoing drama of the day, and I find that despite my efforts at continuous, uninterrupted thought, I am forever beginning afresh, on a new train of thought, or rather the ‘I’ that constitutes my ‘self’ is always just starting up, starting out, that I am continually taking on a new iteration of the self (if that is what it is) at any given point in time.

I start up the forestry track on the west side of Cwm Grwyne Fechan. The ground is boggy after days, weeks of rain, and when the track ends, I enter the forest itself, the peaks of the tall pines forming a dome above my head like the cupola of a cathedral. Light filters through, reminding me of the way that those high, stained glass windows in such places of worship were designed to enchant the faithful, light being the trope that forms the core of ‘enlightenment’. We sit (or stand) in awe of such light, and the great Gothic cathedrals mimic nature in this way.

And when I climb to the track, the familiar well-trodden path up the hill where we sometimes go mushrooming, leading to Pen Twyn Glas, I disturb a pair of ponies grazing by a hawthorn tree, but after a few minutes they become accustomed to me and return to their nibbling of the grass, and I guess that they too have undergone a hiatus in their consciousness, or their sense of self, if they have one, and I have no reason to think that they do not, but equally I cannot be sure that it is configured in a way that resembles my own; I can only report on what I observe, or rather the moments that I notice the world in the spaces between these stops and starts, this meandering of the vagrant self that seems to be as close as I ever get to a sense of what I am. Nor do I think about the future, except in the vaguest possible way, and that, I will concede, is something that has become easy to avoid, with the years.

Perhaps I used to think about the future when I was young: I honestly cannot remember. I think I lived pretty much in the day during my twenties, without ambition, without long term aims, but with the conviction (borne out by absolutely no effort of will on my own part) that I would one day most likely want to write, if only, as Leonard Cohen sings in ‘Famous Blue Raincoat’, to ‘keep some kind of record.’ What sort of record I only had the vaguest idea at the time. I realise, however, as I walk (and later, as I write this down) that the idea of keeping track of the vagrant mind, of registering the stops and starts of thoughts and ideas and memories and insights is an almost impossible task.

Night is falling, and I have no desire to return to the car. I wander and I muse and I track my musings, vaguely, though with less and less concern or even interest: it is impossible to follow the jumping bean antics of one’s train of thought, pointless to try and track the fugitive self as it careens through thought and images, smashing up against the wall of intellect, or rationality. And so, irrationally, rather than follow the rough track to join with Macnamara’s way, just above the Tal y Maes bridge, I decide to go down to the Grwyne fechan, though I know I will not be able to cross it without wading, the stream will be in full flow with all these winter rains, but never mind, I will face that obstacle when I get there: I want to hear the rush of water and see the moon through the branches of the trees at the river’s edge. It is as if I am drawn by some mysterious force to the water, that I need to cross the river there, rather than upstream, at the Tal-y-maes bridge. And it is only when I approach that I understand a little why that might be. I had almost forgotten, but we used to come here for picnics when my daughters were small; and further back, if I am not mistaken, I believe I came here myself as a child for a picnic with my parents, but I cannot be sure; it may be a case of me confusing my own childhood with the childhood of my children. In any case, once I have navigated the boggy ground near the river, I seek out a suitable place to cross. There is not one, of course, as I knew there wouldn’t be.

So I look instead for a crossing point that will soak me only to the shins, and step straight into the stream. Five or six steps and it is done. I climb onto the far bank and my boots are drenched. As the water filters through and soaks my socks and feet, I feel a curious release. I needed to cross the stream, though God knows why. The ascent on this bank is steep and covered in bracken. A fence topped with barbed wire needs traversing to reach the lower field, below Tal-y-maes farm. I clamber up to the path, disturbing a straggle of sheep on my way. They regard me with surprise, a human emerging from the wrong direction. This small gesture, crossing the stream for no reason other than because I wanted to grants me a curious and childish delight. As I walk the remaining mile back to the car I quicken my pace, as the water slops and squelches in my boots.

The hill of wild horses and the nature of risk

Sometimes things fall into place in a way that suggests an omniscient narrator is writing the script, and you are merely a pawn in the plot. On a hill named Pen Gwyllt Meirch — the hill of wild horses (or stallions) — you stop beside a string of them as they graze, just as this pair — who have been nuzzling at each other’s necks as you approach, embark on a silent dance, with only the wind as accompaniment. After their exuberant pas de deux, they return to the group, as the others look on.

You have to find a way toward the ridge, but the path has petered out, and the ridge is an ever-receding goal. This is common enough, in life as well as hill-walking. Here, the soft contours are deceptive, and each rise conceals the next, offering a continuous retreat from view, a problem you give little thought to nowadays.

As a child, walking in these hills, you often felt as though the longed-for ridge would never arrive, and you would nurture a deepening sense that however many times the hillside flattened out to reveal yet another ascent — even as you scurried over gorse and heather — there would always be another rise ahead, and you would never reach the top.

You might say this was an elementary lesson in philosophy. False horizons are always going to mislead you; there will always be another peak and another plateau, just as, in any kind of excavation —downwards, into the heart of the matter, whatever the matter might be — another layer always seems to accrue in the process of discovery, even as you dig. The problems of descent are no less fraught than those of ascent.

But on this mid-May day of uninterrupted sunshine, after months of overcast and wet weather — which nonetheless leaves our reservoirs depleted, because the spring downpours have not compensated for the lack of rain over the past twelve months — there is a spring to your step. You are climbing towards the ridge, and those horses have you thinking of something the French philosopher Anne Dufourmantelle wrote, in her essay, Power of Gentleness: Meditations on the Risk of Living.

‘What the animal disarms in advance, even in its cruelty (outside the range of human barbarity), is our duplicity. The human subject is divided, exilic. If the animal’s gentleness affects us this way, it is undoubtedly because it comes to us from a being that coincides with itself almost entirely.’

And what does it mean, to coincide with oneself almost entirely?

Anne Dufourmantelle might herself provide the answer. She dedicated much of her working life to an examination of risk, of the importance of taking risks, and the need to accept that exposure to any number of possible threats is a part of everyday life, from which we cannot be protected by the false and pernicious security manias of the powers that be. She wrote, regarding risk, that ‘being completely alive is a task, it’s not at all a given thing. It’s not just about being present to the world, it’s being present to yourself, reaching an intensity that is in itself a way of being reborn.’ Her best known work, In Praise of Risk, extols the virtues of risk-taking in words that leave little doubt as to her intention:

‘“To risk one’s life” is among the most beautiful expressions in our language. Does it necessarily mean to confront death — and to survive? Or rather, is there, in life itself, a secret mechanism, a music that is uniquely capable of displacing existence onto the front line we called desire.’

Dufourmantelle drowned in 2017 in the Mediterranean after attempting to save two children, unknown to her, at a beach on the French Riviera, but she did not survive. She swam after them when they got into difficulty in strong winds at Pampelonne beach, near St Tropez, but was herself carried away by the strong current. The children were later rescued by lifeguards and were unharmed, but attempts to resuscitate her were unsuccessful.

Of all the risks we might take, she believed that risking belief was perhaps the most crucial:

‘To risk believing is to surrender to the incredible . . . to surrender oneself not to reason but to the part of the night that lives in us . . . and obliges us to look towards the top.’

Looking towards the top and believing in the summit, even though it is invisible and receding, always on the retreat, is much like staring down into a fathomless pit in which the accretion of nothingness appears impenetrable: is this what you needed to learn as a child? And did you learn your lesson?

Cwm Banw and the Clowde of Unknowyng

There are days when mist covers the Welsh lowlands, all the way from the Canolbarth to the Severn estuary, and yet at around 300 metres above sea level you emerge into bright sunshine, and into a world unimagined to those below.

So it was, driving north from Llanbedr, at a certain point, midway up the valley, the mist is left behind and the world of the sunny uplands (no, not those) opens up ahead, with Pen Gwyllt Meirch (the Hill of Wild Mares) to the right, and the approach to Pen Twyn Glas (the Blue Hill) on the left. You park by the little bridge below Neuadd fawr farm and climb towards the abandoned quarries, where you sit for a while and drink some water, enjoying the view to the south.

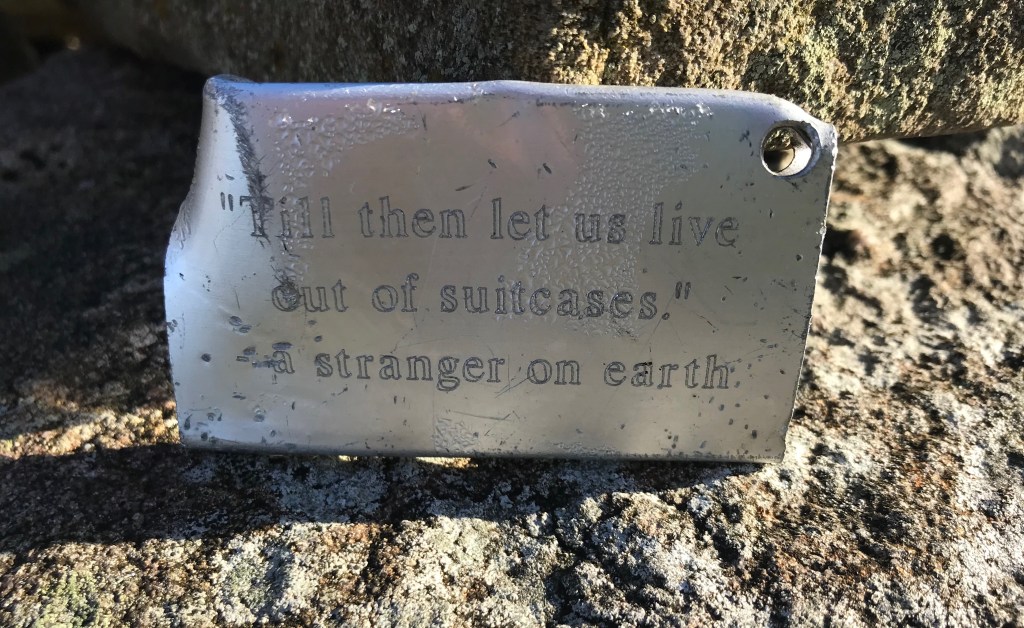

It is only when you stand to pick up your rucksack that you notice the little silver tag, which someone has slipped in beneath one of the stones. You retrieve it, and it reads: ‘”Till then let us live out of suitcases.” A stranger on earth.’ You have no idea why anyone would have those words engraved on a small piece of metal and leave it in a pile of stones on a hillside in the Black Mountains. A serendipitous discovery, or pure chance?

You set off and join the sheep track that skirts Cwm Banw, the valley to which you have kept returning these past two months, as if looking for something that you cannot quite describe or enumerate. This happens sometimes: you have a feeling about a place, and you keep going back until the thing you are seeking out makes itself apparent. But you need to be patient, and you need to be attentive.

There are the remains of a medieval settlement down by the stream, and to the west the summits of Pen Cerrig Calch and Pen Allt Mawr dominate the skyline. But beyond the lower reaches, there are few signs of human occupancy, or even any footpaths. There are sheep of course, and a few wild ponies, and at the far end beneath the ridge that connects Pen Allt Mawr with Pen Twyn Glas, there is the ruin of a tiny shepherd’s hut, where you once stopped for a picnic, but apart from that, nothing but the birds and lizards and moths and worms and bugs and numberless other little creatures, and a few assorted mushrooms, hiding out amid the now flattened fern and the bleached tussock grass and occasional surprising yellow of the sphagnum bogs and the little tinkling rivulets and their surrounding sheathes of brilliant green.

And it dawns on you that there is nothing to prevent you from being someone else entirely; someone kinder, more patient, less critical, more at ease in their own skin. And yet you hang on to character traits and an identity that you might once have worn like a badge of honour, but which you now regard more skeptically, with a degree of weariness. As the years go by, you are less able to keep the performance up, less willing to conform to a pattern of selfhood, or retain a consistent persona merely for the benefit of others. And sustaining this illusion of selfhood interests you less and less. On some days you have real difficulty trying to remember who you are, and what face you must present to the world today. Would it not be a pleasure on those days to let the self unravel, to relax into that comfortable nest of non-doing, and simply watch the day advance, as Thoreau once suggested, without sacrificing the bloom of the present moment to any work; allow the day to advance in such a way that ‘it was morning, and lo, now it is evening, and nothing memorable is achieved’ and be content with that?

And if there is no substantiality to your own sense of self, how can you attribute the same to any other? We are all but fleeting shadows, and it is better by far to remain unknown and obscure to the world.

But (and there is always a but) there is nevertheless the need to present some version of yourself to others, and a job to be done, a salary to be earned, bills to pay, a house to heat, a car to run, all the factors that conspire to make the living of a life more than a mere hypothesis.

And as you sit on a rock and sip tea from your thermos and look down over the valley towards the Sugar Loaf, which sits in the distance like a Welsh Mount Fuji, it seems as though you could step forward and plunge into this viscous sea of white, beneath which nothing is visible and which, it seems, might be nothing more nor less than the Cloud of Unknowing, or, as it was spelled in the fourteenth century, The Clowde of Unkowyng.

Of which the sixth chapter runs, in contemplation of the speaker’s relationship with God:

‘BUT now thou askest me and sayest, “How shall I think on Himself, and what is He?” and to this I cannot answer thee but thus: “I wot not.”

For thou hast brought me with thy question into that same darkness, and into that same cloud of unknowing, that I would thou wert in thyself. For of all other creatures and their works, yea, and of the works of God’s self, may a man through grace have fullhead of knowing, and well he can think of them: but of God Himself can no man think. And therefore I would leave all that thing that I can think, and choose to my love that thing that I cannot think.

And that, I ‘wot not’ ( or ‘I wote never’, as it appears in another version of the text) — meaning ‘I don’t know’ or ‘I have no idea’ — is the only satisfactory response to the question the writer poses. This is the response of attentive and respectful not-knowing.

To dwell in the cloud of unknowing assumes the ability to accept ambivalence and tolerate uncertainty; it demands the courage to say ‘I don’t know’.

Cwm Banw and the myth of core identity

Deep into autumn, with the rich russet or burnt sienna of the ferns, and the grass still so green, with streaks of cloud racing up the valley to our left and, as the mist thickens, an overlay of something more remote and altogether wintry. Walking, something like a refrain begins to emerge, almost a credo about the self, with which I have been struggling all this year, during various walks around these hills, mulling over my reading of certain philosophers and neuroscientists on the notion of core identity. Not that I’ve learned much.

And so to this: when walking in these hills I am most at my ease, no doubt because, through long familiarity, I find it impossible to tell where my self ends and the world begins; or to put it slightly differently, my sense of self ebbs away, dissipates, and is replaced by a kind of harmony with the larger consciousness that we call nature, as if nature were a thing apart from ourselves.

And there it is, the core problem — we speak of nature as though she were a thing ‘out there’, something detached from ourselves, although, in fact, we have made her so, if only to end up craving our return to her safe embrace; a safety which can no longer be taken for granted, such is the violence we have committed against her— and correspondingly against ourselves. And what if this forgetting of ourselves were contagious? What if we were not the only ones to forget our function in the vast mosaic of terrestrial life?

We pass a flock of spectral sheep and veer to the left of the abandoned quarries, following a trail just below the level of the ridge, which skirts the eastern flank of Cwm Banw. There is a kind of silence, though it is always rash to speak of silence. Up here, the song of birds, and the occasional bleating of sheep or the neighing of feral ponies is the most common source of sound at a perceptual level, if we discount the occasional light aircraft (or distant jet planes, whose contrails can be seen high above on a clear day). I make out the call of a skylark or meadow pipit and see the songster flash past, but it moves so quick I cannot tell for certain which it is. And then, for a while, on the descent, we watch a raven circling, and calling frantically, and although I am no ornithologist I know a raven when I see one, and it strikes me as a strange and plaintive cry, more like a duck than a raven. Yes, a raven masquerading as a duck. It feels almost like an aural hallucination, the disconnect between the bird and that call, as though the animal world were falling out of kilter with itself, and even the birds were forgetting their own songs, even as we humans drag the planet screaming towards catastrophe.

I had always imagined that we needn’t worry on that account, that only humans obsess about their core identity, or need to be reminded of their function. Other creatures (and objects) simply go about their business, doing as they must; the stone — to paraphrase Borges — forever wants to be a stone, and the tiger a tiger. Perhaps all that is changing, and everything else is forgetting what it wants to be, as well as us.

Perhaps, it occurred to me, with a gloomy shudder, the birds will forget their song and the furry animals forget to moult and breed and hibernate; perhaps the mycelia will forget to spread and the fungi to sprout and the flowers to blossom. Perhaps it shall all end, not with the bang of climate disaster, but with the whimper of amnesia.

The configuration of confusion

I came to consciousness the other morning from a waking dream in which I had woken (in my dream) into an unfamiliar world, surrounded by strangers in a kind of ante-room, with thick velvet curtains and a single door ahead of me. I knew that I had to make a speech or presentation of some kind and someone mentioned that I would be ‘on’ in one minute. I looked around me — two or three people standing next to me, who seemed to know me well, and were, I imagined, my ‘advisers’. I had no idea where I was or what I was supposed to be preparing to talk about. I guessed, with a vague anxiety, that I would have to ‘wing it’, and that there was bound to be a clue of some kind along the way that would jog my memory. The stress increased, however, when the door was opened for me, and I stepped out onto a balcony, and below me, stretching far across a massive stadium, was a sea of people, a crowd of many thousands, all of them apparently gathered to hear what I had to say. I had no idea what I was supposed to talk about, nor into what world I had awoken, nor even who I was.

When I awoke for real, I didn’t want to open my eyes. Although I knew, or could sense, that I was awake and in my bed, in my own home, there was a residual fear that if I opened my eyes things would be different. There is a comfort, or security, to the ‘inner world’, at times. At least we have some say in it (when awake) whereas what is ‘out there’ is something utterly beyond our control or ability to manage. And that can give rise to fear: hence the ostrich burying its head in the sand, hence the child who closes her eyes because she doesn’t want to see what’s in front of her.

This was all running through my mind last Friday when I walked up above Cwm Banw, following the ridge from Pen Twyn Glas, up to Pen Allt Mawr, Pen Cerrig Calch and down towards Crug Hywel or the Table Mountain. It was a late summer or perhaps an early autumn day with a strong breeze and some interesting clouds.

That sense of closing one’s eyes to block out the world might seem far removed from a consideration of landscape, but it is not entirely so. For me, the landscapes I walk through, and the pictures I take on my iPhone are as much a part of my interior landscape as they are images of the world ‘out there’. When a landscape is familiar, and has been so for many years, then you do not ‘see’ it in the same way as others (who are, perhaps, seeing it for the first time). When a landscape is familiar, you retain an imprint of it on the retina, an expectation of what you will see when you turn your head in that direction. You seek out minor shifts, minute changes by which the image before you is differentiated from the template held in memory. Never before has that landscape been seen from that location with that precise framing of clouds; and so it is actually the first time you have witnessed that scene in that light with that precise configuration of clouds, and for that reason we can never truly say that we have seen anything before because every occasion, every passing millisecond, every present moment is unique and unrepeatable. And just as there is, according to some traditional cultures, ‘meaning’ to be found in the arrangement of a landscape, the arrangement of certain rocks or pebbles, the appearance of an auspicious bird or insect at a particular moment — I am reminded of Jung’s famous scarab beetle appearing at the window of his consulting room at the precise moment his patient recounts the appearance of an identical beetle in her dream — it is the link between the inner world (eyes closed) and outer world of perception (the scenery visible to all of us) that comes to mind when I consider the child closing his eyes to shut out the ‘other’ world, or my own reluctance on certain mornings to open my eyes because of an irrational fear of what I might see.

And if this is confusing, so be it. Confusion too is an inevitable element in the configuration of the present moment. I will accept my confusion, and run with it until it either resolves itself or becomes something else.

Dues serralades

(English version below)

Com a foraster, he intentat entendre l’Albera, la manera com es connecten els camins, i malgrat la qualitat decebedora dels mapes disponibles, he arribat a entendre la topografia del paisatge dels voltants de Rabós. He passat dies llargs i gloriosos fent senderisme per la zona, des del Puig Neulós fins al Coll de Banyuls, els diferents circuits de Sant Quirze i fins a Colera o Port Bou, pel cap de Creus i el cap Norfeu, i pels laberíntics camins que serpentegen per Requessens. Ara tinc un mapa mental de les diferents rutes pels turons dels voltants, i amb cada excursió la meva comprensió s’amplia una mica. A poc a poc començo a veure el territori com un tot, de la mateixa manera que entenc les muntanyes del meu propi país, les Muntanyes Negres de Gal·les – que no són negres sinó verdes, morades i ocres, depenent de l’época de l’any – i que envolten el poble on vaig néixer. Aquestes dues serralades, les Alberes i les Muntanyes Negres, formen d’alguna manera un rerefons del meu món interior, si puc dir-ho així, i totes dues ara se senten com a casa. Se sent com un privilegi conèixer i estimar aquestes dues parts d’Europa per igual.

Així que ens va preocupar molt quan vam conèixer el pla de plantar torres eòliques al llarg de l’Albera, i com molts veïns, vam anar a la manifestació de Capmany l’any passat per protestar contra establiment d’aquestes torres. No és que estiguem en contra de “l’energia sostenible”, per descomptat, caldria estar boig o tenir el cap en una galleda per no admetre que el món està en perill a causa del canvi climàtic, sinó simplement perquè no semblava la manera correcta anar fent coses en una zona d’una bellesa natural excepcional, amb tots els danys que es produirien a l’hàbitat, l’amenaça a les vies de vol dels ocells, la construcció de vies d’accés als molins de vent i els inevitables danys als animals i plantes, sense oblidar l’amenaça potencial per als nombrosos monuments neolítics o fins i tot la simple estètica d’aquest pla. Energia sostenible sí! però no així.

Una de les coses que ha canviat al llarg dels segles al meu paisatge natiu va ser la desaparició dels camins dels pastors i ramaders – d’ovelles i boví – que cobrien les muntanyes durant segles, permetent als pastors portar el seu bestiar al mercat a diferents pobles de Gal·les i a l’altra banda de la frontera d’Anglaterra. Quan es van construir els ferrocarrils al segle XIX, els animals es van començar a transportar amb tren, però amb el temps també van morir els ferrocarrils, i actualment el bestiar es desplaça en camió. Els ferrocarrils de les parts més allunyades del país ja han desaparegut, però els camins dels pastors romanen. I encara hi ha vies més antigues. De la mateixa manera que l’Albera està esquitxada de dòlmens, les Muntanyes Negres van ser un dels llocs preferits pels nostres avantpassats llunyans i contenen les restes de diversos campaments neolítics, que al seu torn van ser els camins fantasma que els posteriors invasors saxons i normands van agafar durant la seva colonització del país. Els normands van construir castells al llarg de la frontera per vigilar els nadius, per mantenir els gal·lesos fora d’Anglaterra.

En almenys una ciutat fronterera anglesa, Hereford, era legalment acceptable disparar a un gal·lès a la vista, tan problemàtics i sense llei es consideraven aquests veïns; però l’efecte a llarg termini va ser mantenir separades les poblacions dels dos països, de manera que els gal·lesos, tot i que van ser la primera de les colònies d’Anglaterra, van aconseguir conservar una bona part de la seva cultura i llengua intactes, molt després que l’Imperi Britànic s’hagués estès a l’estranger cobrint una quarta part de la superfície terrestre. Aquí hi ha correlacions òbvies amb Catalunya, en les seves lluites al llarg dels segles amb un estat militar dominant a Espanya, i l’aposta per l’autodeterminació. Però no ens deixem distreure amb la política: és la muntanya, de moment, la que ens interessa. Hi seran aquí quan tota la resta hagi avançat, sigui quin sigui el futur de la nostra civilització, tant si els nostres respectius països aconsegueixen un estat d’autogovern autònom com si no. Els turons del voltant de Rabós, com algú va dir una vegada, són com dracs adormits, tal com els turons encerclen el meu poble natal, a mil milles al nord. I així els veig jo, dracs adormits bressolant el poble i les terres de conreu que l’envolten, tal com Rabós s’agita inquiet a la Tramuntana i s’adorm en un estupor tranquil durant la canícula.

As a foreigner, I have tried to understand the Alberas, the way that the paths connect, and despite the disappointing quality of the available maps, I have come some way to understanding the topography of the landscape around Rabós. I have spent long and glorious days hiking around the Alberas, from Puig Neulós to the Coll de Banyuls, the various circuits of Sant Quirze and on to Colera or Port Bou, around the headland of Cap de Creus and Cap Norfeu, and along the labyrinthine paths that snake around Requessens. I now have a mental map of the different routes through the hills hereabouts, and with each excursion my understanding expands a little. Gradually I am beginning to see the territory as a whole, in the same way that I understand the mountains of my own country, the Black Mountains of Wales, which are not black but green and purple and ochre — which surround the village where I was born. These two mountain ranges, the Alberas and the Black Mountains, somehow form a background to my inner world, if I might put it that way, and both of them now feel like home. It feels like a privilege to know and love both these parts of Europe equally.

So it became a matter of great concern when we learned of the plan to plant wind towers across the length of the Alberas, and like many local people, we went along to the demonstration in Capmany last year to protest the establishment of these towers. Not that we are against ‘sustainable energy’, of course — you would have to be crazy or have your head in a bucket not to acknowledge that the world is in peril because of climate change — but this did not seem the right way to go about doing things in an area of outstanding natural beauty, what with all the damage that would be caused to the habitat, the threat to birds’ flight paths, the building of access roads to the windmills and the inevitable damage to animal and plant life, not to mention the potential threat to the numerous neolithic monuments or even the simple aesthetics of such a plan. Sustainable energy, yes – but not like this!

One of the things that has changed over the centuries in my own native landscape was the disappearance of drovers’ tracks, which covered the mountains for centuries, allowing drovers to take their livestock to market in different towns in Wales and across the border in England — sheep and cattle, for the most part.

When the railways were built in the nineteenth century, the animals started to be transported by train, but in time the railways died also, and nowadays the livestock travel by lorry. The railways in the remoter parts of the country are now gone, but the drovers’ paths remain. And there are older pathways still. Just as the Alberas are dotted with dolmens, the Black Mountains were favourite locations for our distant ancestors and contain the remains of several neolithic encampments, which in their turn were the ghost-trails the later Saxon and the Norman invaders took during their colonisation of the country. The Normans built castles along the frontier to monitor the natives, to keep the Welsh out of England. In at least one English border town, Hereford, it was legally acceptable to shoot a Welshman on sight, so troublesome and lawless were these neighbours perceived to be; but the longer-term effect was to keep the populations of the two countries separate, so that the Welsh, although the first of England’s colonies, managed to retain a good deal of its culture and language intact, long after the British Empire had spread overseas to cover one quarter of the earth’s land area. There are obvious correlations here with Catalunya, in its struggles over the centuries with a dominant military state in Spain, and the bid for self-determination. But let’s not get distracted by the political: it is the mountains, for the moment, that interest us. They will be here when everything else has moved on, whatever the future of our civilisation might be, whether our respective countries achieve a state of autonomous self-government or not. The hills around Rabós, as someone once said, are like sleeping dragons, just as the hills encircle my home village, a thousand miles two the north. And that is the way I see them, sleeping dragons cradling the village and the farmlands around it, just as Rabós stirs restlessly in the Tramuntana, and slumbers in a tranquil stupor during the dog days of summer.

The Black Mountains and the human brain

There are days when the cloud cover is so dense and hangs so low that earth and sky are within hand’s reach of each other. We are all familiar with that sense of atmospheric density and its emotional charge, especially here in Wales, and certainly in the Black Mountains, that no man’s land between one country and the other, or as Raymond Williams almost said, between two sets of others. And as I mentioned in my last post, the quality of light on such days offers a world viewed through an amber or yellow lens — which reminds us that in alchemy the colour yellow has a particular valence: it stains and infects, carries with it the suggestion of corruption, of pus and bile, of an insidious contagion.

I am curious about the Black Mountains as a site of alchemical experimentation, and in my novel The Blue Tent I explored that idea with a backward glance towards the 17th Century Welsh alchemist Thomas Vaughan.

We might think of the seasonal shifts as a kind of alchemy. These are sometimes startling, and provide entirely different perspectives of the same landscape over the course of a year; as here, in two photos of the Tal-y-maes bridge, in the Grwyne Fechan valley, taken in January and August respectively.

But I have noticed something else, over the years, which I am certain is not unique to my experience. I have discovered on many occasions that just because a path appears on the map, it doesn’t mean it’s there. On the other hand, and perhaps more pleasingly, there are paths that exist on no map. And there is something else too, that we might call phantom paths, or paths that go missing. In his book The Hills of Wales, Jim Perrin has written about this idiosyncrasy of the Black Mountains: ‘There are places here I have seen in the past and been unable to find again, as though they had disappeared from the land.’

You are in a place you’ve been a hundred times before, but it has somehow changed, been reconfigured in your absence, and the land laid out before you has taken on a different aspect, so much so that it feels like another place entirely. It’s almost as though there were a shadow version of these mountains, an alternative or parallel massif, that you access, unsuspecting, along a familiar path or track, and within minutes you are somewhere else; not lost exactly, just somewhere you hadn’t expected.

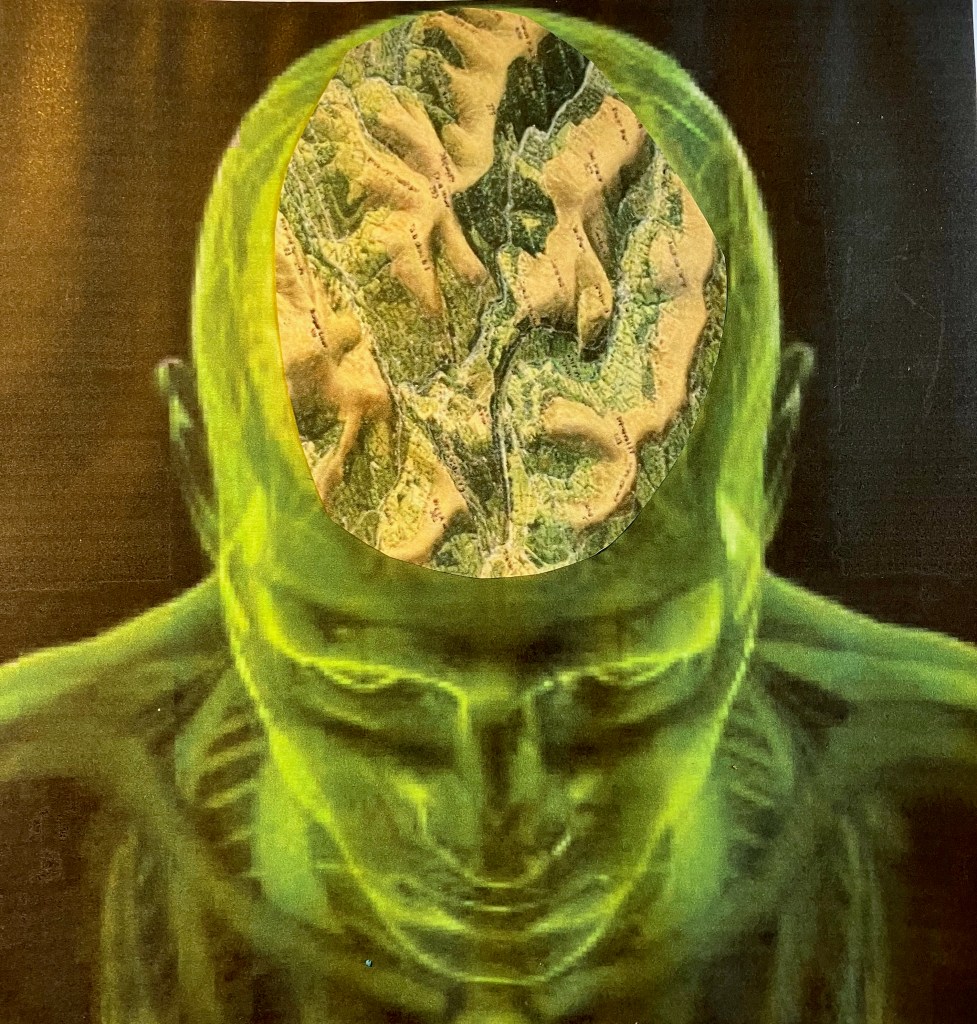

In this no man’s land of the Mynyddoedd duon, the geography is sometimes malleable, shifting: it is the geological equivalent, I think, of the brain’s neuroplasticity, which has been defined in the Journal Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience, as ‘the ability of the nervous system to change its activity in response to intrinsic or extrinsic stimuli by reorganizing its structure, functions, or connections.’ That’s it: the Black Mountains as a human brain! It is kind of shaped like one, don’t you think? With the Grwyne Fawr valley forming the central furrow, the left side comprising Grwyne Fechan, Cwm Banw, Pen Allt Mawr and Pen Cerrig Calch, the right side comprising everything to the east — from Darren yr Esgob, across the Ewyas Valley, Offa’s Dyke ridge, the Cat’s Back etc. And what if it reorganises its structure by minute degrees according to the external stimulus of quantum measurement — or of human observation? The relief map on my bathroom wall now makes more sense: it represents the territory of the Black Mountains as a massive brain, through which we might walk, and, who knows, have our minds truly blown.

Capel-y-Ffin and the many worlds interpretation

Although the name Capel-y-Ffin is often associated with the idiosyncratic Catholicism of Eric Gill and David Jones (and I will return to them in another post), the hamlet is also home to both a small Anglican church and a Baptist chapel, which lie almost side by side in quiet rivalry. In Wales, according to the old joke, there is always ‘the other place’, the one you don’t go to. Curiously, considering the number of times I have passed through, I had never ventured into either of them until a couple of weeks ago, when I visited both. The little church of St Mary the Virgin, as Kilvert wrote, ‘squats like a stout grey owl among its seven great black yews’, and venturing inside, it feels almost as if I have entered one of those tiny sanctuaries hidden away in the Greek mountains, because the art work has a decidedly Orthodox flavour. There is also a David Jones hanging by the staircase, to the right of the door. Or should I say a copy, or print of a David Jones, as the Tate in London claims to own the original.

It is early morning, and after a week of hot weather — one of our famous heatwaves — we are entitled to some rain, which duly arrives as I climb to Darren Llwyd, following the track to the Twmpa, also known as Lord Hereford’s Knob. As I go along, I am vaguely pondering Thoreau’s commendation that ‘to affect the quality of the day, that is the highest of the arts.’ And how do you go about that? Not, I imagine, through conscious effort, but rather through a kind of non-doing, of which walking, if done without perturbation or hurry, might be an example. Letting things be and allowing thoughts —if they must come — to unfold in their own way. Slowing down. Today will be a slow walk. I will strive to be responsive to the quality of the day, as Thoreau has it.

But there is a problem. I’m preoccupied by an article I’ve recently read about the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics, and it has raised a few issues. Or re-raised them, I should say. The article, by Philip Ball, which appears in Quanta magazine, and which I happened across while surfing without purpose, challenges what it calls ‘the most extraordinary, alluring and thought-provoking of all the ways in which quantum mechanics has been interpreted.’ I won’t go into the argument that Ball makes in his article, largely because it is quite technical and I don’t understand the physics. But in essence, the many-worlds interpretation (MWI) suggests that there are a near-infinity of universes, all of them superimposed within the same physical space but isolated from one another and evolving separately. (It should not be confused with the multiverse hypothesis, in which there are countless other universes, each originating in a different Big Bang, which are distinct and separate from our own). In the MWI, the other worlds contain replicas of you and me, but they are leading other lives, doing things that we do not. As Ball’s article points out, the many worlds interpretation is highly seductive: ‘It tells us that we have multiple selves, living other lives in other universes, quite possibly doing all the things that we dream of but will never achieve (or never dare to attempt). There is no path not taken.’

It’s a sort of comfort to know (or rather, to imagine) that there are innumerable versions of oneself doing stuff in other worlds, and the idea makes us feel less alone. It provides a sort of balm for all the fuck-ups of one’s past: at least in one of those other worlds a version of myself acted otherwise, and the idea offers a strange kind of release, or even salvation. The idea appeals to the religious instinct, I suppose, and at the same time softens the tyranny of memory, which adds to its appeal.

I have written about this elsewhere on this blog, in relation to a story by Borges, The Garden of the Forking Paths, which contains the following passage:

‘Your ancestor . . . believed in an infinite series of times, in a dizzily growing, ever-spreading network of diverging, converging and parallel times. This web of time – the strands of which approach one another, bifurcate, intersect, or ignore each other through the centuries – embraces every possibility. We do not exist in most of them. In some you exist and not I, while in others I do, and you do not, and in yet others both of us exist. In this one, in which chance has favoured me, you have come to my gate. In another, you, crossing the garden, have found me dead. In yet another, I say these very same words, but am an error, a phantom.’

This notion of infinite outcomes to any situation is a source of perennial fascination to Borges, and the idea seems especially feasible in this part of the world, the Black Mountains: I often get the sensation, when walking or driving across Gospel Pass and down into the Ewyas valley, of entering a zone where, more than elsewhere, the laws of everyday reality disintegrate. It is perhaps in the nature of borders, as liminal zones, but the notion is especially powerful here. Looking east, the road towards Hay snakes along the mountainside like a road in a children’s story book, and as I reach Hay Bluff, and the wide Wye valley stretches out below me, I am struck once again by the yellow, almost rusty light of these uplands on days, like today, of low hanging cloud. It is like looking at the world through an amber filter.

My route now follows the Offa’s Dyke path leading towards Hatterall Hill, with the Olchon Valley to my left. I follow it with tiring footsteps in the persistent drizzle, and only when I come to the turning off point, two miles south, does the weather clear. The unexpected sunshine adds a spring to my step, and I descend rapidly down a steep path through shoulder-high ferns, almost to the valley road, but turn off just before, along a pretty, wooded track, one of those paths best encountered in the early evening light of a summer’s day. And before joining the valley road, on the right, stands the Baptist Chapel. The building itself is closed up, and I can’t go in, but there is the demure and mossy graveyard, and a most hospitable bench, in which I can sit and take it all in. It is a wonderfully tranquil spot, beside an especially imposing yew tree. There are worse places to spend eternity, I imagine: at least for this version of you, either in this or whichever world you find yourself.