A Perambulation with Providence

For some time now, I have been wondering about the idea of Providence. It all started with a quotation from Goethe, about the importance of fully committing oneself when setting out on a new project:

‘The moment one definitely commits oneself, then Providence moves too. All sorts of things occur to help one that would never otherwise have occurred. A whole stream of events issue forth from the original decision which you never dreamed of before.’

While this might sound like a kind of magical thinking to some readers, I do not think it is. I find it quite feasible to believe that once you have decided on a course of action things fall into place around you, so long as the commitment is there. Nonetheless, the notion that something called ‘Providence’ moves with me is the bit I have always wondered about. I have checked it out, of course (I do my prep) and uncovered the definition of Providence, courtesy of Lexico.com as ‘the protective care of God or of nature as a spiritual power’. Meanwhile the OED provides ‘the foreknowing and protective care of a spiritual power, specifically (a) that of God (more fully Providence of God, Divine Providence etc), and (b) that of nature. ‘Nature’ will do, after a fashion, though I honestly can’t think of ‘nature’ as something discrete, extraneous, ‘out there’. It’s the process or dynamic through which we exist. Neither am I crazy about the word ‘spiritual’. It is vague and has too many associations with practices that I find either suspect or presumptuous. But I’m inclined to keep things simple, and will equate ‘God’ with ‘Nature’ here. Providence as the protective care of nature.

I do not pretend to be a philosopher, nor do I have any training in that discipline or dark art, nor am I what might be strictly termed ‘religious’, but I am curious, and as it happens I drop in from time to time on a podcast called The Secret History of Western Esotericism (SHWEP) presented by a man who goes by the name of Earl Fontainelle.

While I am driving up to the Black Mountains from Cardiff early this August Monday morning I listen to an episode, fortuitously titled Providence, Fate, and Dualism in Antiquity. I had not planned this: it was the episode that was next in line.

Given the episode’s title, I am listening out for a definition of Providence, and sure enough, up one pops, or rather up pop several, courtesy of Earl’s interviewee, Dylan Burns, author of Did God Care?: Providence, Dualism, and Will in Later Greek and Early Christian Philosophy.

It would seem, according to Dr Burns, that Providence began its linguistic journey as the prónoia of the Greeks, meaning forethought, and became known in Rome, by Cicero’s day, as providencia. The concept comes up in ancient esoteric texts constantly, I learn, and well into the Middle Ages, where it came to mean the way that God determines Fate, something we would regard as deterministic. This suggests that free will was not a given; we are all subject to some ulterior force that is in a strong sense antithetical to free will, and that is Providence. However, as Dr Burns explains, just because certain things, such as universal laws, are determined by the gods (or God), it doesn’t mean that we are relieved of the responsibility to make the right choices. So, as I understand it, some things are up to chance, others are predetermined by the gods, and yet others can be brought about by the choices made by men and women: that which is up to us. We have free will but should never forget that there are certain things over which we have no control: shit happens.

There’s more, but that’s about as much as I can take in for now. I need to think a little.

Leaving the car at the roadside in Capel y Ffin, I set off up the road towards Gospel Pass, but after 300 metres take a left over a stile, up across a field past a cottage called Pen-y-maes; then follow the path that hugs the hillside below Darren Llwyd, before descending to the covered road just below Blaen-bwch farmhouse.

A quarter of a century ago, when Blaen-bwch was a working farm, I was once nipped on the shin by an over-enthusiastic sheepdog while coming down this lane. I have never forgotten, because it is the only time I have been bitten by a dog. This time there are no dogs, but outside, on the little patch of grass before the house, sit three humans in the lotus posture; two men and a woman. They are wearing loose robes and one of them, the woman, has a wooden bowl in her lap. What is that? Surely not a begging bowl; there’s only a slim chance anyone else will pass this way. Especially on a Monday. Perhaps it’s a gong of some kind. Perhaps it wasn’t made of wood, but bronze. I walked past too quickly to take it in. The meditators are silent, with eyes closed. I feel a wave of slight weirdness as I pass, emanating from one of the meditators, a long, haggard white man, the eldest of the three, who has the look of a self-proclaimed guru. Not hostile weirdness exactly, but a definite vibe of something, and not entirely to do with loving kindness, something more like propriety. It says something like: this is our patch. I can’t help making these evaluations, and am probably wrong, but there you are. When I am thirty metres past the house I stop to tie my bootlace, but really I just want to have another look. The third one, an Asian guy, has his eyes wide open and is watching me; until, that is, he sees that I am watching him, and closes his eyes in the prescribed manner, presumably to continue meditating. I wonder what these people would make of the Providence and free will debate.

The sun is getting warmer. It is forecast to be in the high twenties today, but up here the heat will be easily endurable, thanks to the mountain breeze. I have a hat and suncream, lots of water and a big thermos of spiced tea. I follow the course of the stream, Nant Bwch, and pass the little pool where Bruno the Dog once carried out an infamous atrocity. The spot has gone down in family legend as the pool of the duckling massacre.

A little further up, on my right is the promontory known as Twmpa, or Lord Hereford’s Knob, but I am heading left, or west. I pass a group of five cyclists in their sixties, all men who hail me cheerfully in the accents of the Gwent Valleys. They pass me, one after the other, negotiating the uneven track calling out in my direction: alright butt?; wonderful out yer, innit; lovely day; have a good hike, butt, etc. When they have passed out of sight I sit for a while on the rocks at Rhiw y Fan, overlooking the Wye valley, with the hamlet of Felindre beneath me.

I’d like to fall asleep because I only managed two hours last night, the usual struggle with insomnia until I got up and did some writing around 4.00 and never made it back to bed. But I need to get a shift on, and so head towards the trig point at Rhos Dirion, and there I sit down again, my back propped up against my rucksack and am about to drop off, when I see a very young woman in shorts, tanned legs, athletic build, plaits swinging, who approaches the trig point and proceeds to walk around it in rapid circles, as if she were a wind-up toy, or simply cannot stop moving. I wonder what she is doing out here alone, when I hear voices, crane my head around, and see a small mob of youths approach. From their accents I deduce they are the Essex kids from Maes y Lade residential centre. Two boys in the vanguard of the group address the solitary girl: ‘What are you on, Victoria?’ says one, evidently amazed that she has arrived at the meeting place a good few minutes before any of them. ‘Yeah, what’s Victoria’s secret?’ chimes another lad, the class wit. Victoria, pretty, coy, unspeaking, continues to circle the trig point at speed.

More kids are arriving now, throwing themselves on the ground and bringing out picnic packs and my peaceful interlude has been disturbed, so I move on, westward again, until I come to the track that marks the path of the Grwyne Fawr valley, and I turn south and follow the nascent stream.

I know this path well, love the way it descends through the gradually steepening valley above the reservoir, with the hillsides collapsing in on either side. A little way down I pass a family of ponies. They stop stock still when I take a photograph, as if posing. Then, when I move on, they resume their grazing.

I am getting hungry and stop by the stream, which is beginning to run above ground now, take off my boots. The stream bed is covered with sphagnum, which provides a deliciously soft pillow for my aching feet. A few metres downstream a pony is chomping away at the grass on the bank. She looks over her shoulder at me when I sit down, but does not move away. I feel an intense wave of wellbeing, strip down to my underwear and unpack my meal. I don’t much like eating out in the sun, but there is no shade to be had here, or anywhere near.

After eating, I drink hot chai, and then take myself off to a flat patch of ground. The skeleton of a sheep lies nearby — but is it a sheep, I wonder? Everything has become a little unreal, as though I were watching through a lens in which the colours are both bleached out and stunningly vibrant at the same time, and I cannot decide whether the skeleton belongs to a sheep, or . . . . but I am simply too tired to be bothered by such matters. I greet the skeleton anyway, addressing it as Geoffrey — the first name that comes to mind — and tell it I’m sorry for its loss. I lay out my rain jacket on the grass and lie flat on my back, close my eyes.

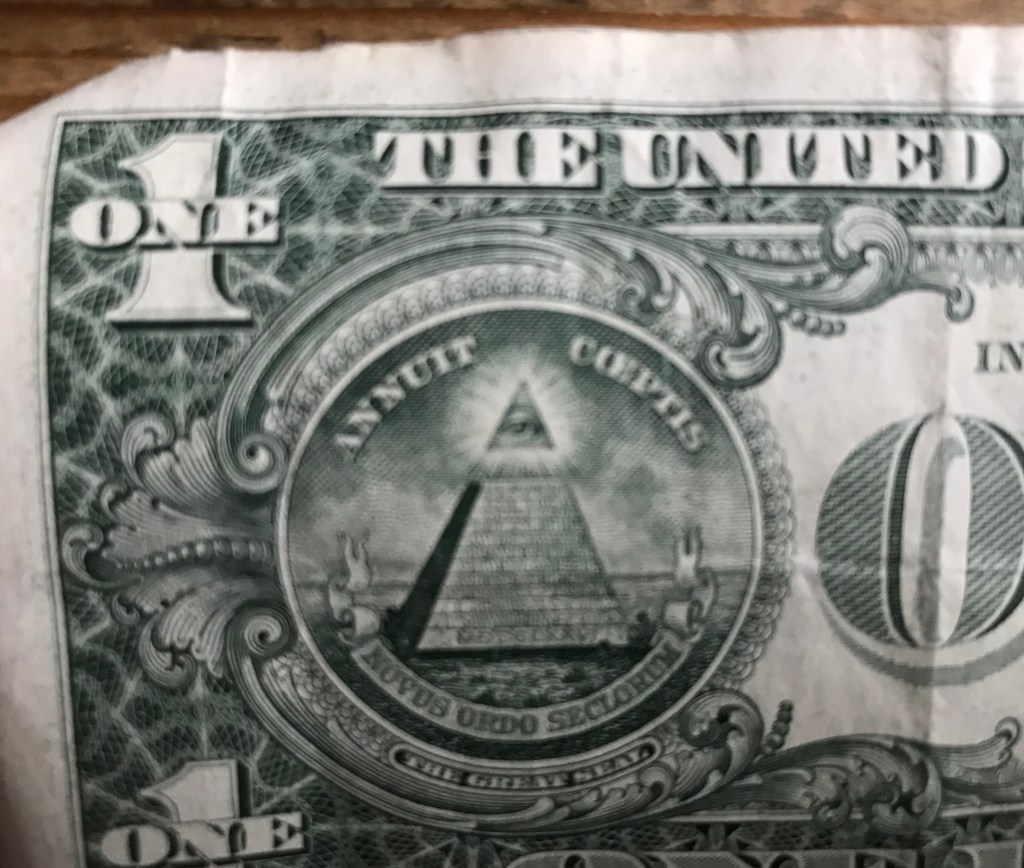

I must have slept for only a few minutes, but I wake with the image imprinted on my consciousness. It is, I know, the Eye of Providence: one of those eyes contained within a triangle that appears universally in religious iconography, from Ancient Egypt onwards. The all-seeing eye of God. The eye is everywhere. It counts every hair on every head and every grain of sand. The eye appeared in late Renaissance art as a symbol of the Holy Trinity. The eye is even printed on the one dollar bill, such is its reach. That eye is monitoring even the most minute financial transactions in the world’s biggest economy.

I am not usually given to conjuring such symbols. I must have invoked it by listening to that podcast. Providence is in the air. And there was its eye, projected onto the inside of my own eyelid when I awoke from the briefest slumber.

I set off down the valley towards the reservoir, passing more ponies on the way. The breeze is a godsend, as it is pretty warm by now. I keep a steady pace and when I reach the dam I veer left at forty-five degrees along a rough track towards the ridge of Tarren yr Esgob, and then take the track south, heading for the blacksmith’s anvil just below Chwarel-y-fan. I am not thinking of anything much at this point, am at that stage of the hike when the mind goes blank, and you simply walk, one foot following the other. And it is then that I notice the flying ants. Hundreds, if not thousands of them, flying in an opaque black cloud just behind my right shoulder. The air is black with them, but none of them are actually bothering me, and I think of them as some kind of diabolical escort — the phrase comes easily to mind after seeing the Eye and all that it entails — as though I were some warrior from an ancient myth come to avenge a terrible murder — perhaps Geoffrey’s? — with a delirious swarm of flying ants at my side. There are none of the insects to my left, the side of the Ewyas Valley; all of them are to the right of me, a dense miasma of evil, or so I suspect. I accelerate, and the cloud accelerates. I stop, and the insect horde hovers closer, a few of them landing on my shoulder and chest, which is no good, that’s not part of the deal, so I brush them away and set off again. I devise a plan to be rid of them. I shall be utterly calm, and rid myself of any trace of stress or inner disquiet. I will be like Don Juan in the Carlos Castaneda books, who was never troubled by flies, not even in Mexico. I don’t know for sure whether that is what does the job, but after another quarter of a mile of serene walking the flying ants drift away, and by the time I arrive at the blacksmith’s anvil, they are gone. I sit on the stone and drink another chai.

The descent leads me down the steep hill below the rocks of Tarren yr Esgob, past the ruins of the monastery of Llanthony Tertia, onto the tarmac lane and back to the car. As I change into trainers for the drive home, a blackbird starts up in the bushes at the roadside. Evening birdsong never was more lovely.

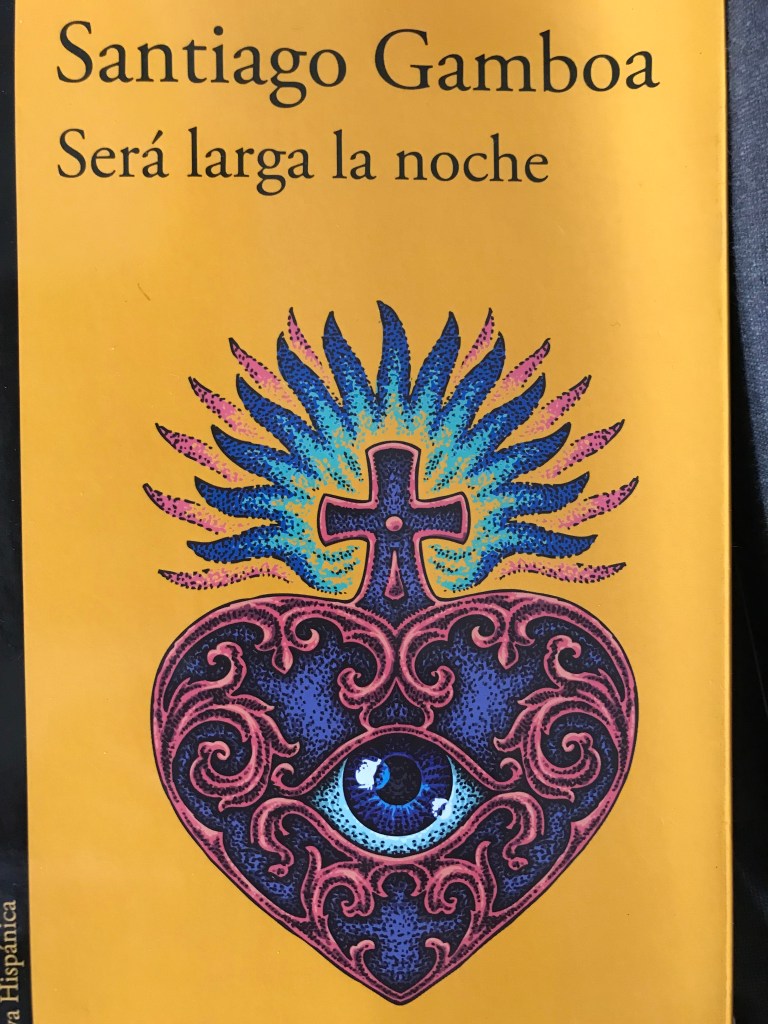

Later, when I am home and getting ready for bed, I pick up the topmost volume of a pile of books that I have to read for a translation competition I am judging. On the cover, to my utmost surprise, and satisfaction, is depicted the Eye of Providence.

A quiet stroll along the ridges

I map out a circular route that begins and ends at the Tabernacl chapel, a third of the way up the Grwyne Fawr valley. I plan a route because I have become more fastidious, as I get older, about leaving clear directions at home, just in case. This notion of following a predetermined route is something quite alien to me, however, and it goes against every fibre of my being to stick to it, not to veer off on subsidiary trails, onto paths that lead nowhere, or else to places I never imagined going. Especially those places, in fact.

And so it is, quite early one morning in late July, that I park the car opposite the chapel and set off up the hillside. I keep to a rhythm, there is nothing original in that, it’s the only way to go, one step leading to another. But that’s why it feels so good. The rhythm of the breath. I pass the badger-faced sheep, which, on this particular farm, have been known to give me the evil eye. Below the Stone of Revenge, I take the lower path, which, after half a mile or so, follows the eastern flank of the Mynydd Du forest. I turn sharp right onto a rough trail up to Bal Bach, and from there the vista opens up over the Ewyas Valley, with Llanthony Priory directly below.

From here I climb to Bal Mawr, and it is now that the green becomes greener, to my eye, at least; a green, as a poet once said, that is close to pain. In the distance, to the south, the Severn Sea is visible. Only on a clear day, and there aren’t so many of those. I stop to drink water, and am greeted by a solitary hiker, a man of around my age, walking in the opposite direction. He is the only human I have seen since leaving the road, and I will not see another for at least three hours, and then at a distance. Which is odd, even for a Tuesday.

A line comes to mind from a book I recently read, which has been playing on my mind. Augustus John’s biographer, Michael Holroyd, writes that John could never be one person, that he didn’t know who he was, that he kept reformulating himself (as an example he says that John kept changing his handwriting). Solitude on these walks often stirs up lightly dormant threads of thought, and I am at once cast adrift on the shores of an old and bitter dispute, brought on by that ‘could never be one person’; whether, indeed, there is such a thing as core identity, reinforced by the continuous tellings and retellings of a discrete and autonomous self, the narrating ‘I’ of its own life story, or whether, rather, we are episodic beings, as the philosopher Galen Strawson proposes, a sequence or series of fleeting ‘selves’ that dissolve and reassemble in different iterations over the course of a lifetime, but which lacks any central unifying narrative that constitutes what we might reasonably think of as a ‘self’. But does it have to either/or? Can I not be the bearer of (or container for) a more transitory and fleeting self and yet retain an underlying constancy, of the kind once called a soul? These ruminations are brought to a close when I spot what looks like a carved tombstone, a rectangular and large white rock, thirty metres below the ridge. I scramble down to inspect it, only to find it is a natural rock, covered by a strange scabby whiteness, some kind of fungus, nothing more.

As I follow a vague track down from Tarren yr Esgob towards the Grwyne Fawr reservoir, a tiny chick adorned with flecks of fluff, peers up at me from the mat-grass. This baby bird is a meadow pipit, and when I stop to take its portrait, I hear the worried chirruping of a parent bird nearby, and so move on.

At the reservoir, the water level is the lowest I have seen it, and although swimming is not encouraged, it certainly isn’t unheard of — and I have swum here myself. No one, though, would be tempted by the water today.

A hundred years ago, when the reservoir was under construction, some of the workers would commute by foot from Talgarth each morning, and back again at night, a walk of around seven arduous miles each way, following the stream north, and descending down Rhiw Cwnstab. My plan was to head the same way, as far as the stream’s source, and then turn left up toward Pen y Manllwyn and Waun Fach, but at this point, having crossed the bridge at the head of the dam, and noticing tracks straight up the hillside toward Waun Fach, I take a short cut. I want to get home before nightfall. The path is very steep, so I stop off to feast on whimberries (or winberries, or billberries, or whortleberries) — but known locally as whimberries — which grow abundantly here. Unfortunately they do not keep well, and reduce to mush very quickly in warm weather, so I don’t take any home.

The summit and environs of Pen y Gadair Fawr is sacred ground, at least for me. I stop to eat my sandwich and gaze in wonder at the majestic lines that sweep down between Pen Trumau and Mynydd Llysiau, allowing the distant shape of Mynydd Troed to slip perfectly between them, as an elegant foot might slip inside a cosmic slipper.

The Mynydd Du forest lies to the east of the ridge, a vast conifer plantation covering over 1,260 hectares that stretches half the length of the valley. For the past fifty years this forest has been a blot on the local landscape. In its recently published ‘Summary of Objectives’, Cyfoeth Naturiol Cymru/Natural Resources Wales claims that it will aim to ‘diversify the species composition of the forest, with consideration to both current and future site conditions, . . . will enhance the structural diversity of the woodland . . . incorporating areas of well thinned productive conifer with a wide age class diversity, riparian and native woodland, natural reserves, long term retentions, and a mosaic of open habitats.’

That is all well and good, and I only hope it comes to pass, because the argument for the planting of native broadleaves has been around for decades now, and in the meantime expanses of the mountain are stripped bare (the term ‘asset strippers’ comes to mind) leaving an ugly void, as the conifers drain the soil of nutrients. I reflect back on a conversation I had with a farmer in the Grwyne Fechan valley last year, who told me how the forestry companies are supposed to plant a percentage of deciduous trees in among the pines, but the approach is tokenistic at best, or else frankly cynical: profit and exploitation of resources is the only serious motive. The landscape I pass to the south of Pen y Gadair Fawr looks and feels like a deserted battlefield. An arboreal graveyard. Nothing much is alive, apart from the few sheep that nibble listlessly at the edge. I feel the usual useless rage, and continue on my way.

Further on, I come across a flattened patch of grass between the ferns, scattered with wrappings from protein and chocolate bars, empty cans of energy drinks, crisp packets, used tissues. I look around. The rubbish covers quite a small area, and there is a breeze, so the litter louts have not long gone. I gather up all the mess and fill the plastic carrier bag that I use as a damp-proofing cushion, and stuff the lot inside my rucksack. Who on earth would leave their trash behind in a place like this? When I round the next hillock I see, in the distance, a group of half a dozen young people crowded around a map that one of them is holding; Duke of Edinburgh participants perhaps? Who else under the age of fifty would use an actual paper map? They look as if they are descending towards the Grwyne Fechan valley road. I think of going and gently explaining things to them, but they are too far away. As I watch, they seem to work out their route, and move on down the hill. I decide not pursue them, and do a stunt as the crazy old man they met up a mountain. It’s wonderful (I want to think) that these kids have an opportunity to walk in these hills, but could they please do so without trashing them? The next day I will ring around a couple of places that provide accommodation for groups of this kind, at Llanthony and Maes y Lade. Neither of them had excursions up in the hills yesterday, they say. I have quite a long chat with the guy from the Maes y Lade Centre, which is run by Essex Youth Service and provides residential holidays for youngsters from that county. He seems genuinely concerned and insists that the kids who come to the centre are taught to respect the local environment. That’s good, I say, and mean it.

Forms of sphagnum have been around for 400 million years, and the soft, absorbent moss has been used widely for poultices, for nappy (or diaper) material by Native Americans such as the Cree, and as insulation by the Inuit. What strikes me most about this little patch of moss or migwyn, however, is the almost luminescent colour, a blend of orange, white and gold that startles in the light of late afternoon, the moss dotted with strange upright stalks, daubs of white fluff attached, resembling candy floss. I think at first it must be sheep’s wool that has adhered to the stems, but it is lighter, fluffier, and more fragile to the touch. I am flummoxed and make a mental note to research my sphagnums.

The last stretch of the hike involves a slight ascent up to Crug Mawr, high above Partrishow and its tiny church. Looking west I catch the full contours of the Table Mountain, the iron age fort of Crug Hywel, which lends its name to my native town, Crickhowell, lying beneath it, out of sight. As I sit there in the silence, a red kite appears, glorious in its poise, suspended in impossible stillness high above the trail that forms the Beacons Way, no doubt scanning for any small rodent unwise enough to twitch beneath the ferns. It hangs there for a brief and delicate eternity, barely ruffling a feather, before suddenly swooping, levelling out and gliding at speed a few feet above the ground, then falls upon its prey, which it holds between its vice-like talons and soars away.

The descent towards the valley lane and the chapel is not kind on the knees after these fourteen miles, and I feel the weight of the years. When I get to my car I am joined by an eager young sheepdog, who throws herself into the stream ahead of me, an invitation of sorts. I take off my boots and sit on a rock, my grateful feet soaking in the cold water as the hound frolics briefly in the shallows, gnawing on a stick, before she is called away by a farmer’s whistle. It is evening now, and a cool breeze blows down the valley. I drink the last cup of hot chai from my thermos, smoke a cigarette, and reflect once more on the notion of the self, and core identity, before dismissing the notion entirely, and throwing away the dregs of my tea. My own core identity, if I ever had one, has dissolved into the flickering remnants of the day.

A tight knot of mermerosity

When we set out, just past Castell Dinas, we pass a dog driving a tractor. Or so it seems.

The shadow of Bruno the dog is long. We see him everywhere. Every morning when I first go downstairs I expect to see him, lying on his rug by the front door. Making coffee I expect him to approach me, nuzzle the back of my knee with his snout. I expect him to stand by the back door, waiting to be let out for a pee and on returning inside to stand by the fridge, awaiting his treat. But he isn’t there.

In David Shield’s book, Reality Hunger, I come across this:

‘In English, the term memoir comes directly from the French for memory, mémoire, a word that is derived from the Latin for the same, memoria. And yet more deeply rooted in the word memoir is a far less confident one. Embedded in Latin’s memoria is the ancient Greek mérmeros, an offshoot of the Avestic Persian mermara, itself a derivative of the Indo-European for that which we can think about but cannot grasp: mer-mer, ‘to vividly wonder,’ ‘to be anxious,’ ‘to exhaustingly ponder.’’

The Chambers dictionary of etymology links ‘mourning’ and ‘mourn’ with old Saxon ‘mornian’, to mourn, and Old High German mornen, Icelandic ‘morna’ — but goes on to say ‘cognate with Latin memoria (mindful) see MEMORY’. So I look at ‘Memory’ in the etymological dictionary and sure enough, Shields is right: ‘Latin memor is cognate with Greek mérmēra = care, trouble, mermaírein = be anxious or thoughtful.’

Mermeros was a figure from Greek Mythology, a son of Jason, along with Pheres. Apparently the brothers were killed either by the Corinthians or by Medea, for reasons that vary depending on the rendition (see Medea). In one account, Mermeros was killed by a lioness while out hunting.

Iolaus mermeros is a butterfly of the Lycaenidae family. It is found on Madagascar.

Mermeros in ancient Greek means ‘a state of worry or anxiety’.

I find a blog written by the Australian environmental philosopher Glenn Albrecht, who applies the concept of mermeros to the crisis of the world’s ecosystem: ‘Perhaps we should expand the psychoterratic typology beyond an established term such as ‘ecoanxiety’ to include a concept like ‘mermerosity’ or what I would define as the pre-solastalgic state of being worried about the possible passing of the familiar and its replacement by that which does not sit comfortably within one’s sense of place. I begin to mourn for that which I know will become endangered or extinct even before these events unfold. I know and worry that the coming summer will be too hot and will have a huge wildfire threat. I often have a tight knot of mermerosity inside me when I consider the scale of negative change going on around me and what disaster might happen next.’

Albrecht goes on to suggest that a new kind of mourning ‘might contains the emergent elements of detailed knowledge of causality, anthropogenic culpability and enhanced empathy for the non-human’ . . . ‘The etymological origins of the word ‘mourning’ come from the Greek language, mermeros related to ‘a state of being worried’ and its meaning is associated with being troubled and to grieve. We can see from these ancient origins that mourning is a versatile concept that can be applied to any context, present and future, not just to the death of humans, where there is grieving and worry about a negative state of affairs.’

On the day of Storm Eunice, I walk with my daughter Sioned up to Pen Trumau, starting from Castell Dinas, just off the Crickhowell to Talgarth Road. Castell Dinas was an Iron Age Fort that later sprouted a Norman Castle, of which the ruins are still visible. At 450 metres it is the highest castle in that hybrid geo-political entity ‘England and Wales’. It has the dubious privilege of having been sacked by two Welsh warlords, first by Prince Llywelyn ap Iorwerth in 1233 and subsequently by Owain Glyndŵr on his visit to these parts circa 1405, on his way to Crickhowell. He burned down the castle there also.

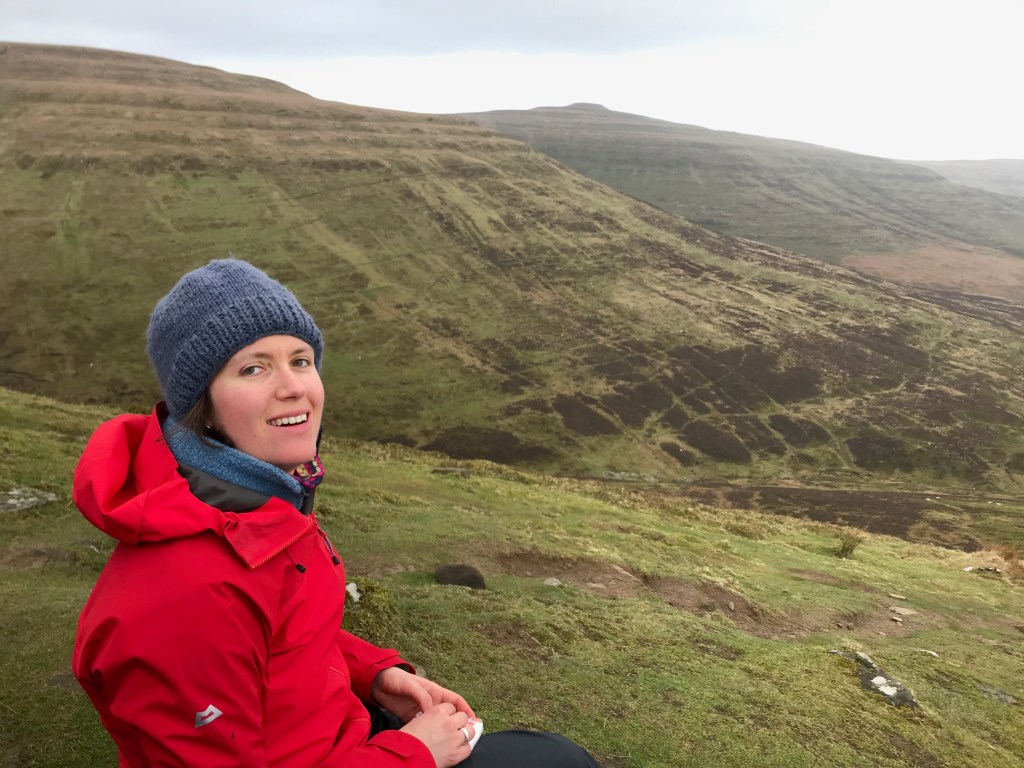

On the south-west facing side of Pen Trumau we are out of the wind, but once on the ridge beneath Mynydd Llysiau we struggle to stay on our feet: leaning into the wind becomes an effort of the will. There is no way to depict the wind in a photograph of a treeless landscape, but the posture tells us pretty much all we need to know about the wind.

By the time we hit the ridge between Pen Trumau and Waun Fach we realise that the effort required to walk is more than we can sustain. I am tired and out of sorts in any case; since Bruno’s death I’ve been enduring a kind of failure to engage with thought, which drains my energy. Sometimes I feel I’m better off not thinking at all, that I’d rather be merely sentient, like a beast of the field. So much cerebral processing in the human. And for what?

As we descend from the mountain, and I look down over Cwm Grwyne Fechan, and beyond, to the ridge behind Pen Allt Mawr and westward, and I notice once more the way that the hills fold into one another creating a trompe l’oeil effect, the curve of a hillside concealed by another, a process of continual enfolding, that reminds me of something to do with grammar: the Black Mountains as a single recursive sentence, its hills clauses hidden within other clauses, disappearing from sight as you round a contour or cross a ridge.

The Olchon Valley and Walter Lollard

The Olchon Valley, which I only discovered recently, is a place that feels as though it shouldn’t exist. It is almost the definition of somewhere lost to the world; undiscovered, little known even to those who walk its outer edge, Crib y Gath, or the Cat’s Back, the long spine of an enormous dormant beast that threatens to uncoil, thrash loose and send its cargo of walkers flying into the stratosphere, perhaps to be picked up by some errant wind and deposited on the Malverns (from Moel fryn, or bare hill) to the east or Pen y Fan to the west. The looping elliptical lane that follows the contours of the valley is an ouroboros, a serpent eating its tail. Who knows where its tales of sorrow and loss will take us. Walking down the lane, past derelict cottages, we get the impression that this was once quite a populous valley. Whatever happened? There were times when parts of the Black Mountains flourished, and the fourteenth century was certainly among them.

Rumour has it that in 1315 Anabaptist leader and vagabond Walter Reynard of Mainz (known also as Reynard Lollard, and in the Dictionnaire des hérésies, des erreurs et des schismes as Gaultier Lollard) — an outspoken critic of the Catholic hierarchy — came to Wales, and was offered refuge in Olchon.

As one account has it: ‘Walter the Lollard, a shining light in the midnight of Papal darkness, after passing from country to country, lifting his eloquent voice and scattering over the wintery seed-fields the germs of truth, passed through England to build up the scattered flock of Christ there, and then breathed out his great soul amid the fires of martyrdom.’ Lollard was burned at the stake in Cologne, in 1322.

What did he find here in this obscure valley? Does his ghost haunt these silvered lanes on a night in February, the stars like shingle on some immeasurable shore? Do the religious wars that engulfed Europe over the three hundred years that followed Walter’s visit have their origins in a seed sown in this narrow sleeve of land between the great ridge of Hatterall and the Cat’s Back?

On the Cat’s Back

Sometimes our reading maps onto our walks. Or vice versa. The night before I had been reading in Raymond Williams’ People of the Black Mountains how Glyn goes in search of his Taid one evening, when the older man fails to return from a long walk in the hills. He has left a note for this daughter, Megan, and grandson Glyn, which includes the lines:

‘It is such a lovely day, so still and bright, that I’m taking a lift back . . . so that I can go once again along the best of all walks through these mountains: what you’ve heard me call its heart line. I shall go up by Twyn y Gaer and along its old pastures to the Stone of Vengeance, then to the old circle at Garn Wen and the Ewyas tower, along the ridge above the reservoir . . . across Gospel Pass and along the ridge to Penybeacon, then as always above Blaen Mynwy and past Llech y Ladron to our spot height above Blaen Olchon and so along the Cat’s Back to the Rhew and the lane to the house.’

A conversation has just taken place between Glyn and his mother, Megan, in which Megan has expressed concern about her father’s late return:

‘Has he been well?’ Megan asked, forcing her voice.

‘Yes, as usual. He’s got so much more energy than the rest of us.’

‘Seems to have more energy.’

‘Yes, because he lives in one piece.’ ‘

‘He’s sixty-eight, Glyn.’

‘In one piece, in one place. It makes all the difference.’

So that is the opening premise, and like Glyn, who sets out to do his Taid’s walk in reverse, we ventured up Crib y Gath (the Cat’s Back) in his footsteps. Given that it was a day of low hanging cloud in late December, our expectations were limited, but I was also deeply conscious of my own investment in these mountains, and of what I have learned about them, and continue to learn, over many years. Williams also had thoughts, which he expressed, via his protagonist Glyn, in another passage:

‘Solid traces of memory! The mountains were too open, too emphatic, to be reduced to personal recollection: the madeleine, the shout in the street. What moved, if at all, in the moonlit expanse was a common memory, over a common forgetting. In what could be seen as its barrenness, under this pale light, there might be the sense of tabula rasa: an empty ground on which new shapes could move. Yet that ideal of a dissident and dislocated mind, that illusion of clearing a space for wholly novel purposes, concealed, as did these mountains, old and deep traces along which lives still moved. An empty and marginal land, in which the buried history was still full and general, was waiting to be touched and to move.’

Over the past month, over several excursions, I have become accustomed to a very particular light in which these hillsides bathe when the cloud is thinning and the sun is about to drop behind the western skyline. The effect of this densely filtered sunlight — beginning about an hour before sunset — is to cast an amber wash over everything, so that the whole spread of the upland; the peat bogs, the wide expanse of tussock grass and sphagnum, all of it, is luminescent with an understated warming glow. Unfortunately, this light does not translate.

The state into which I plunge is paradoxical; both deeply present and yet strangely detached, as though, like Williams’ protagonist, with ‘dissident and dislocated mind’ I too were ‘moving over an empty ground on which new shapes could move’.

For a moment, then, I consider this steep-sided ridge, Crib y Gath, as a mighty ship, plying the deep pasturelands, into a sea of mist. At the far prow, on a rocky outpost, can be seen a single figure — my daughter Rhiannon — unwittingly performing the lead role in a Caspar David Friedrich painting. To the right, the cloud covers the Olchon valley and creeps up the walls of Hatterrall Hill. In that moment everything lies fully within view, circumscribed by mist and as improbable as the hawthorn that sprouts at right angles to the rock. In fact the entire landscape creates its own rules of harmony, lives by its own innate rhythms. There is a symmetry to it all, which I cannot fathom, but which, as the years pass, seems ever more deeply to resemble a kind of consciousness.

Above the fog line

There is a world above the fog line, as we discover. Two hundred and fifty metres above sea level, we emerge into a landscape filled with colour. The sky is a cerulean blue. Like the inhabitants of Plato’s cave, we are stunned to learn of the existence of this brave new world. If we return to the world of fog the others will not believe us, and may kill us. We can see the fog lands stretching out beneath us, to the river valley, southwest to the capital, and far beyond. Best to stay put.

We hear gunfire from further up the cwm: men are hunting with dogs, which is against the law of the land. There is a woods, and the way is perilous, but we make it onto the upland pastures of Darren fach, the disused quarries of a deeper green than even the grasslands, the sheep dropping currants, the various fungi now at season’s end, among them the liberty cap, psilocybe semilanceata, the collection or possession of which is against the law of the land: but whose land? Three watchful horses graze where once there were two. Who is the third that always walks beside us? We sit by the cairn and eat our sandwiches, drink hot tea from a thermos. I wonder whether the farm that lies at the base of a perfect parallelogram, below Pen Gwyllt Meirch and surrounded by three fields — three adjacent parallelograms — was built there by design or by accident. Or whether the design — if indeed that is what it is — stretches far beyond that corner of the hillside to encompass all of this, and us.

Or whether that particular shade of russet, edging to ochre, or is it saffron — no colour chart could do it justice — can ever be replicated in a photograph or painting, any more than I, seated beneath the cairn, knife in hand, dropping apple peel for the luminous insects at my feet, might discern the vast and intricate pattern of spider webs that lattice the entire hillside and which glitter like a silvery counterpane under the oblique rays of the winter sun as it falls behind the bulk of Pen Allt Mawr.

Coming off the mountain, one of the horses, silhouetted against the mist — which has edged up the valley just a tad — eyes us with suspicion. The air is colder now. Retracing our steps down the forestry track, a pair of deer appear from our left at speed, leap across the path ahead of us, and vanish.