How do people live?

How do we construct a life as we go along? The things we do and say, the actions that make us who we are? Sometimes all of this is bewildering. I look for clues everywhere, including under the bed. I find a few empty boxes, some crayons, a broken hunter watch belonging to Taid (my grandfather) which saw out four years in the trenches in World War One but was not able to resist my two-year old daughter swinging a toy hammer. Bits and pieces.

Tom Pow, the Scottish poet, told me the other week that he had been working in a prison and a disturbed long-term inmate had started declaiming, to the world at large, How do people live? – a question perhaps more appropriate, and less taken-for-granted than might at first appear.

Part of the aim of this blog is to reflect on the mutable universe, and the roles that we play within it. One of the delights of having a camera app on your mobile phone is that you can snap things at random, which taken together in the course of a day can cast a peculiar light on that very general plea, made by the prisoner of how do people live, at a very unspectacular level. It is something I will never grasp entirely, but which can be illuminated by these fragmented moments, taken at intervals with no plan or purpose, amounting to a broken narrative of what passes by. With no plan or purpose, but always stalked by memory.

Ancient tree at the bottom of Gypsy Lane, Llangenny. When I was a kid it blew my mind to learn that this tree was here when the Normans arrived.

Good things about being Welsh: No. 5

a) Grand Slam.

b) Singing and shouting like a loon.

c) Soaking it up afterwards.

Odds and ends

Here’s a salutary tale. The past few days Blanco’s Blog has gone viral, thanks to the occurrence in a one-off post last summer – a film review of Hobo with a shotgun – of the word penectomy. Shit, I’ve done it again.

There are thousands of people out there, it seems, who get terribly excited when they get a sniff of a word like ****ctomy, and they then let all their chums know, and on it goes. A few of the more specialist sites, it seems, advocate different forms of self-mutilation, including auto-castration.

I don’t know what other clinical terms I should be avoiding, but no doubt if people send in suggestions, we might between us break my new all-time record.

On second thoughts, please don’t.

On a lighter note, I have been spending a lot of time toing and froing to the fair city of Birmingham these past two weeks. What friendly and plausible folk those Brummies are! Why on earth do they get such bad press? It can’t be due to their irrepressible chirpy good humour. It must be that, in sociolinguistic terms, they speak the most maligned and ‘disfavoured form of British English’, according to all opinion polls and surveys carried out since time began. According to one source:

A study was conducted in 2008 where people were asked to grade the intelligence of a person based on their accent and the Brummie accent was ranked as the least intelligent accent. It even scored lower than being silent …

Oops. People are such bigots. An entertaining and fair account intended to dispel negative stereotyping of all things Brummie can be found here.

Meanwhile, as we in Cardiff gear up for the Grand Slam showdown with France on Saturday, the London press goes on an adoration fest for the ‘England’ rugby team. Sure, the defeat of France on Sunday was admirable, but do The Times, Telegraph, Guardian and Independent really need to spend pages and pages describing the Sweet Chariot revival, and only a few column inches on the champions-in-waiting, when, after all, the best the Saeson can reasonably hope for is second place?

Good things about being Welsh: No. 4

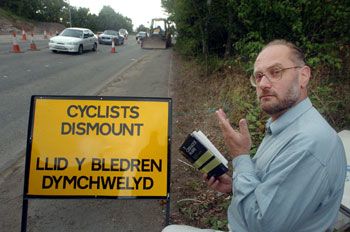

We in Wales are recklessly uninhibited in our fondness for signs. We will put anything on a sign, however nonsensical, and leave it out for all to see. Consider the photograph above, taken on a country road in the Vale of Glamorgan. ‘Toads’, it says. Well? Is no further explanation required? I wait for a while in a nearby car-park, lest coachloads of amphibians should pass by, perhaps clutching little pennants, or else dressed in goggles and flying jacket, like the famous Toad of Toad Hall. But no cigar.

Let’s take another one:

I particularly like this bi-lingual sign near my house, on the river footpath, warning of the possibility of a tumble into the swirling waters of the Taff. I like its succinctness of composition and I especially like the upstretched arms of the falling man. It seems to be telling me something other than that which it purports to be telling me, but I am not quite sure what this is, and it leaves me with a stab of uncertainty each time I pass it.

This mania for signs, I realise, is not uniquely Welsh, but I sometimes think that we are the best at it, since we can do them bi-lingual in ways that the language planners never conceived. There are many beautiful examples of this, and I will sign off with one of my favourites. The Welsh in this sign warns cyclists not – as the English might lead them to expect – to get off their bikes, but that ‘bladder disease has returned’. Truly, we are a musical nation.

Synchronicities

Whenever I mention the brother, who is an actual person, and not a figment of my deranged speculation, I am reminded of Myles Na gCopaleen (aka Flann O’Brien, aka Brian O’Nolan) and his famous column in The Irish Times, which occasionally featured a character known as ‘the brother’. This character is used as a foil, or a useful source of handy sayings. He is the source of the timeless phrase ‘The brother cannot look at an egg’, for some reason one of my favourite sayings of all time, and one which I repeat to myself as a mantra in times of trouble, and sometimes intone out loud, to the bewilderment of my breakfast companions.

Anyhow, the brother – who is evidently, and I must say, gratifyingly, a keen reader of Blanco’s Blog – sends me two quotations from the ‘Wit and Wisdom’ column of The Week. How nicely synchronous of them to find stuff directly related to my posts of 24th and 27th February. The first quote is particularly gratifying, coming as it does from one of my favourite living writers.

“I’ve been fortunate that all the bad reviews I’ve had have been written by idiots. Isn’t it weird how it works out like that?” (Geoff Dyer in The Guardian)

“The best minds of my generation are thinking about how to make people click ads. That sucks.” (Mathematician Jeff Hammerbacher in The Daily Telegraph)

In Praise of Coffee

Who first thought to pluck the coffee bean from a tree, dry it, do to it the complicated things that need attending to, and brewing a hot cup of the stuff? Like so many other human discoveries, the odds on this ever happening seem so remote as to defy imagining. I mean, why would anyone bother? And how many horrible concoctions did people try out before hitting on the right one? How many were fatal, and how many caused the ardent experimenter to call out ‘O God, why did I try to smoke/drink that?’ But there seems no lack of ingenuity in humans’ attempts to eat, drink, imbibe, smoke or snort just about every leaf, bean, bark or blossom under the sun. And why not.

I have just opened, and brewed a pot of the sample on the left of the picture, an espresso roast from Las Flores plantation, Nicaragua. It is delicious and strong, but unlike other dark roasts doesn’t leave any nasty metallic aftertaste. I wish I could share a cup with you, although rumour has it that Coffee a Go Go in Cardiff’s St Andrew’s Place have a small allocation, which is their guest bean today.

On my recent trip to VIII International Poetry Festival of Granada in Nicaragua, I retuned with my suitcase laden down (it hit 27 kilos so I had to plant some on Mrs Blanco – has anyone tampered with your luggage madam . . ) not with tomes of poetry (there was some of true value, and I think I got what I needed there) but with a selection of coffee beans. While there, we also enjoyed a tour of one plantation, where we learned, for example, that due to the delicacy of the small sprigs, the coffee beans have to be hand-picked with a gentle downward movement, because if the stems are bent back the wrong way, they will not produce fruit the next year. This is backbreaking and demanding labour, and cannot be carried out recklessly.

I spent several winters in my younger years picking olives, and (depending on the location, and the destination of the olive) this activity can be carried out with varying degrees of vigour, but none of them involve quite such a delicate technique as coffee-picking.

And then there’s the wages paid to the pickers. On most plantations this is minimal – and their living conditions appalling, which is why it is important to try and buy coffee from a responsible source – not easy when half the coffees in the supermarket are labelled under the ambiguous (and almost meaningless) ‘Fair Trade’ label.

A good cup of coffee is a priceless thing, and those beans have made quite a journey. It makes one wonder if there are any decent coffee poems. So I do a search, and am delighted to find there is an entire literature reflecting our love affair with the bean, notably in a site titled, usefully, a history of coffee in literature.

Here is an example, from the little known (early 19th century?) English poet Geoffrey Sephton, extolling the virtues of Kauhee (or coffee) as opposed to those nasty opiates that were all the rage at the time:

To The Mighty Monarch, King Kauhee

Away with opiates! Tantalising snares

To dull the brain with phantoms that are not.

Let no such drugs the subtle senses rot

With visions stealing softly unawares

Into the chambers of the soul. Nightmares

Ride in their wake, the spirits to besot.

Seek surer means to banish haunting cares:

Place on the board the steaming Coffee-pot!

O’er luscious fruit, dessert and sparkling flask,

Let proudly rule as King the Great Kauhee[1],

For he gives joy divine to all that ask,

Together with his spouse, sweet Eau de Vie.

Oh, let us ‘neath his sovran pleasure bask.

Come, raise the fragrant cup and bend the knee!

O great Kauhee, thou democratic Lord,

Born ‘neath the tropic sun and bronzed to

splendour

In lands of Wealth and Wisdom, who can render

Such service to the wandering Human Horde

As thou at every proud or humble board?

Beside the honest workman’s homely fender,

‘Mid dainty dames and damsels sweetly tender.

In china, gold and silver, have we poured

Thy praise and sweetness, Oriental King.

Oh, how we love to hear the kettle sing

In joy at thy approach, embodying

The bitter, sweet and creamy sides of life;

Friend of the People, Enemy of Strife,

Sons of the Earth have born thee labouring.

Should writers reply to their critics?

Should writers respond to their critics? I have discussed this with several writer friends over recent years. The consensus seems to be a resounding No, because once you get involved it is difficult to back out with dignity. If you get a bad review, it sometimes smarts for a while, but you usually get over it. Even people who claim never to read their reviews seem to be remarkably up to date about what others have written concerning their work.

Even a poor review can sometimes contain within it a small gem that can be turned to one’s own advantage. The Times’ disparaging and bitchy review of my first novel referred to the book as ‘superior lifestyle porn’, which we were able to recycle as (sort of) praise. It was OK because lots of other reviewers said very nice things about the book. You learn to take the rough with the smooth. Professional reviewers get paid (usually a pittance, in my experience, but something, at least) for writing their pieces, so should at least take their job seriously. I think it is cowardly and idle not to give a review a thorough evaluation and spend some time on it, rather than just dish out some cheap shots or (as is often the case) string together a few clichés and call it a review.

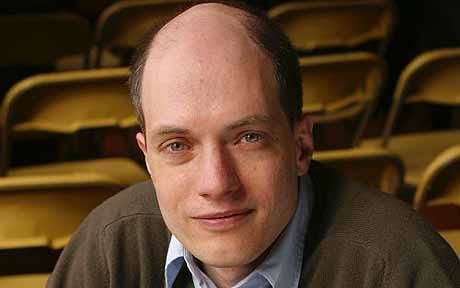

Alas, there is also the serious personal attack, posing as a review, as famously endured by Alain de Botton in the New York Times a couple of years ago.

According to the Daily Telegraph report (I never read the Telegraph, except for the cricket, but I shall cite it in order to make ‘Sue’ (see below) feel justified about her accusations):

The outburst followed a poor review of de Botton’s book The Pleasures and Sorrows of Work, by Caleb Crain in The New York Times.

The author, whose books include Essays in Love and The Consolations of Philosophy, lost his temper during a posting on Crain’s blog, Steamboats Are Ruining Everything.

“In my eyes, and all those who have read it with anything like impartiality, it is a review driven by an almost manic desire to bad-mouth and perversely depreciate anything of value,” he wrote. “The accusations you level at me are simply extraordinary.”

He went on: “I genuinely hope that you will find yourself on the receiving end of such a daft review some time very soon – so that you can grow up and start to take some responsibility for your work as a reviewer. You have now killed my book in the United States, nothing short of that. So that’s two years of work down the drain in one miserable 900 word review.”

The author, who has written widely about the pursuit of happiness, concluded: “I will hate you till the day I die and wish you nothing but ill will in every career move you make. I will be watching with interest and schadenfreude.”

This makes me smile. It is what many of us would like to say, but don’t, because we never come out of it looking well.

Sometimes a review is particularly lazy and ill-informed – not really a review at all – and clearly the writer responsible hasn’t taken the time to read the thing at all, or else is simply a foolish person, a bigot, or a cretin. Or all three.

Which brings me to Goodreads, that democratic website that allows citizens to parade for all to see what books they are reading, what they plan to read, and even what they think of what they have read. Apart from wondering why on earth anyone should care, it seems a perfectly harmless sort of thing to do if you have plenty of time on your hands.

So, to cut to the quick, the other day I came across a ‘review’ of my book The Vagabond’s Breakfast on Goodreads, posted by ‘Sue’ who accuses me of writing ‘middle class poop’.

Let’s consider this accusation for a moment, if only to wonder who among the proletarian hordes – for instance, where I live in Grangetown, Cardiff – would use the term ‘poop’? Surely this critic is giving herself away too easily. But worse than this, she accuses me of writing fiction under the pretext that it is truth, in other words, of being a liar.

Sue’s general gist is that I made some, or all, of the book up, though how she has reached this conclusion, she does not make clear. In a later post – where she has morphed into Redwitch379 – she claims that I myself have said that my book is a ‘fictional autobiography’. Have I? I don’t think so, Sue. So that is galling. And I am thinking up a curse to match de Botton’s. If Sue really is RedWitch379, she had better hang onto her broomstick.

But this is one of the glories – and pitfalls – of the internet. You can hide behind another identity. True, Blanco is a pretty thin disguise, especially as my picture is at the top of the page and most people who comment on this blog seem to know me. The truth is that as well as encouraging a wide-ranging and, at the best of times, stimulating platform for intelligent discussion, websites like Goodreads also allow every fucking idiot on the planet to have a voice, which, of course, is exactly how it should be.

A modest epiphany

From left: John Galán (Colombia), Iman Mersal (Egypt), Frank Báez (Dominican Republic), Tom Pow (Scotland).

Sometimes a short poem hits the mark, for no particular reason, and without providing any easy way of explaining to others the random pleasure it delivers.

I am looking through Postales, an intriguing book of poems by the young Dominican poet Frank Báez – for me one of the finds of the Granada Poetry Festival – and I notice this little gem, a sweetly ironic homage to Ginsburg:

Miaow

I haven’t seen the best minds

of my generation and nor does it bother me.

In the original:

Maullido

No he visto las mejores mentes

De mi generación y ni me interesa.

Carnival photos

Here are a few pictures from Wednesday’s carnival in Granada, Nicaragua, where The Tears of Disenchantment (or broken-heartedness) were buried, allegedly.

Briefing from Nicaragua

At four in the morning there is a noise of riotous celebration from the nearby square, but I cannot be bothered to make it to the balcony to discover its source. Then there is an hour or so of quiet before the deafening screech of birdsong that signals both the beginning and the end of daylight in the tropics. From the trees circling the park hundreds of birds dance, joust, leap and dive in a frenzied avian fiesta.

Yesterday began with an excursion to the cloud forest volcano of Mombacho – in which we saw howler monkeys

and many birds, including the black headed trogon (trogón cabecinegro, in Spanish) pictured here,

after visiting two coffee plantations, sampling their delicious brews, and witnessing a possum asleep in a bucket

– and concluded with an interminable poetry reading, extremely mixed in quality, but beginning with a single (new) poem by Ernesto Cardenal on the sacking of the museum of Baghdad, and ending with Derek Walcott, again reading a single poem, Sea Grapes. Between these two octogenarian maestros – and with one or two exceptions – a number of distinctly indifferent poets went on for far too long, though I will refrain from mentioning the worst offenders.

Granada is an extraordinary festival, which is growing in importance and recognition, but which needs reining in and the exertion of greater balance in the selection of invited poets. This year, like last, I have met some wonderful individuals, made new friends, and learned a lot, but have also had to listen to far too much bad poetry. Fortunately, Walcott’s Sea Grapes does not fall into this category.

Sea Grapes

That sail which leans on light,

tired of islands,

a schooner beating up the Caribbean

for home, could be Odysseus,

home-bound on the Aegean;

that father and husband’s

longing, under gnarled sour grapes, is

like the adulterer hearing Nausicaa’s name

in every gull’s outcry.

This brings nobody peace. The ancient war

between obsession and responsibility

will never finish and has been the same

for the sea-wanderer or the one on shore

now wriggling on his sandals to walk home,

since Troy sighed its last flame,

and the blind giant’s boulder heaved the trough

from whose groundswell the great hexameters come

to the conclusions of exhausted surf.

The classics can console. But not enough.

Or you can listen to Walcott reading it here.

Brief from Nicaragua

At four in the morning there is a noise of riotous celebration from the nearby square, but I cannot be bothered to make it to the balcony to discover its source. Then there is an hour or so of quiet before the deafening screech of birdsong that signals both the beginning and the end of daylight in the tropics. From the trees circling the park hundreds of birds dance, joust, leap and dive in a frenzied avian fiesta.

Yesterday began with an excursion to the cloud forest volcano of Mombacho – in which we saw howler monkeys

and many birds, including the black headed trogon (trogón cabecinegro, in Spanish) pictured here,

after visiting two coffee plantations, sampling their delicious brews, and witnessing a possum asleep in a bucket

– and concluded with an interminable poetry reading, extremely mixed in quality, but beginning with a single (new) poem by Ernesto Cardenal on the sacking of the museum of Baghdad, and ending with Derek Walcott, again reading a single poem, Sea Grapes. Between these two octogenarian maestros – and with one or two exceptions – a number of distinctly indifferent poets went on for far too long, though I will refrain from mentioning the worst offenders.

Granada is an extraordinary festival, which is growing in importance and recognition, but which needs reining in and the exertion of greater balance in the selection of invited poets. This year, like last, I have met some wonderful individuals, made new friends, and learned a lot, but have also had to listen to far too much bad poetry. Fortunately, Walcott’s Sea Grapes does not fall into this category.

Sea Grapes

That sail which leans on light,

tired of islands,

a schooner beating up the Caribbean

for home, could be Odysseus,

home-bound on the Aegean;

that father and husband’s

longing, under gnarled sour grapes, is

like the adulterer hearing Nausicaa’s name

in every gull’s outcry.

This brings nobody peace. The ancient war

between obsession and responsibility

will never finish and has been the same

for the sea-wanderer or the one on shore

now wriggling on his sandals to walk home,

since Troy sighed its last flame,

and the blind giant’s boulder heaved the trough

from whose groundswell the great hexameters come

to the conclusions of exhausted surf.

The classics can console. But not enough.

Or you can listen to Walcott reading it here.