The day my hard drive died

Worse things happen, obviously, certainly. But it was the suddenness of the event that most surprised me, after having the damn thing switched on for around five years and using it around the clock. One moment it was there doing my bidding, the next it is casting grey questions marks at me through a grey mist in a singularly humourless way.

I probably shouldn’t have spent so much time on the roof with it. It must have had a touch of the sun. But then again, I have heard that the generation of macbooks late 2006 to mid 2007, such as mine, suffered a design fault, but Apple, not wishing to lose their impeccable image, did not do a general recall but simply put a notice on their website saying if anyone wanted a change they could have one. Bunch of bastards.

And now I have lost some not inconsiderable notes on a half-written novel, a couple of stories, who knows what else. As well as millions of photos and lots of music. I am going to have to send the machine to one of those specialist forensic outfits that you see on programmes like ‘Spooks’ and await their decision. But I reckon Apple should pay, since it now appears that whole generation of macbooks had dodgy hard drives.

All this talk is sending me to sleep. Still not recovered from a couple of very late nights followed by early mornings.

I knew a man called Question Marco once, a skinny rodent-faced Spanish beggar, in San Sebastian. A haunted-looking fellow with a bent spine, hence the sobriquet. This was in the days before people started thinking nicknames were cruel and heartless. I was hanging out with a big German called Kurt who was always falling over and consequently his face was covered in bruises and welts and scratches. He told me a joke once that went on for ages and ended with the line ‘so why don’t you cement your garden?’ followed by this manic obscene laugh, hyeugh hyeugh hyeugh, which, like Pig Bodine’s, ‘was formed by putting the tonguetip under the top central incisors and squeezing guttural sounds out of the throat.’

Question Marco was shaped like a question mark, and his heart was a question mark, and everything he said ended in a question mark. With such a man there is never anything to be gained by a direct approach. For such a man the world begins and ends with a question to which there is never a reliable answer.

Miscellaneous sightings

This car was parked on the road near a pool in the river Muga where I like to swim. Who said the Germans have no sense of humour? It certainly wasn’t me. I might however begin an occasional series on this blog titled ‘Exploring National Stereotypes’ or ‘Exploding National Stereotypes’. This would be #147.

Beware of reading? This book contains a bloody funny joke? Other possible interpretations to Blanco please.

This parakeet now lives in The Sad Giraffe Café, in Sant Llorenç de la Muga. I am uncertain why the sad giraffe had to go, but when I asked the new owner of the café she looked at me as though I were an imbecile. Sometimes I don’t know whether to keep my mouth shut or just come out with stuff. And the sad giraffe has left. The parakeet is quite nice, but I preferred the giraffe, who sang.

As ever on Blanco’s Blog, one thing leads irrevocably to another. I photographed this spider’s web on Friday, and over the weekend, reading David Mitchell’s The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet, I come across a passage in which the observation of spider webs is said to have influenced early engineers in bridge design:

‘At old days’ says Miss Aibagawa, ‘long ago, before great bridges built over wide rivers, travellers often drowned. People said,”Die because river god angry.” People not said, “Die because big bridges not yet invented.” People not say, “People die because we have ignoration too much.” But one day, clever ancestors observe spider’ webs, weave bridge of vines. Or see trees, fallen over fast rivers, and make stone islands in wider rivers, and lay from islands to islands. They build such bridges. People no longer drown in same dangerous river, or many less people . . .’

However, spider silk is interesting of itself. An article in Interface, the Journal of the Royal Society, entitled High-performance spider webs: integrating biomechanics, ecology and behaviour offers the following enticement:

“An integrative, mechanistic approach to understanding silk and web function, as well as the selective pressures driving their evolution, will help uncover the potential impacts of environmental change and species invasions (of both spiders and prey) on spider success.” If this interests you as much as it does me, read on here.

What is a Classic?

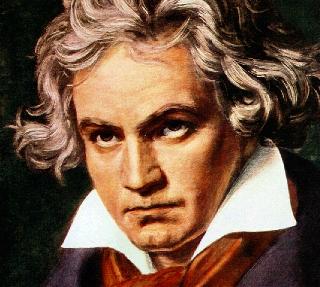

A couple of days ago I blogged about John Franklin’s moment of clarity while listening to a late Beethoven sonata in 1845, less than twenty years after it was composed. The music had – according to Sten Narodny’s account in The Discovery of Slowness – an epiphanic effect on the explorer, and in the novel he is made to endure a sublime moment of self-realisation.

Then yesterday, reading J.M. Coetzee’s essays, I come across an autobiographical anecdote of how Coetzee, at fifteen years of age, heard harpsichord music drifting across the garden fence from a neighbour’s open window in his Cape Town suburb, and the effect this had on his life. The music was from Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier and, writes Coetzee: “As long as the music lasted, I was frozen, I dared not breathe. I was being spoken to as music had never spoken to me before.” This despite the fact that his family home was bereft of music, that he received no instruction in music, that classical music above all was “sissy” and regarded by Coetzee in a “somewhat suspicious and hostile teenage manner”.

But somehow Bach’s music breaks through to the boy, “speaks to” him, as Coetzee puts it. And in his essay ‘What is a Classic’ the adult author wonders whether his adolescent response to the music back in 1955 was “truly a response to some inherent quality in the music rather than a symbolic election on my part of European high culture as a way out of a social and historical dead end.” Since the essay’s title marks it out as a response to T.S. Eliot, and Coetzee is concerned about the emergence of the term Bach as a touchstone, and a classic as being, in at least one sense, ‘that which survives’, we end up depending (argues Coetzee) on criticism to define and sustain notions of the classical.

Which is all true, but by resorting to an argument about the nature of the classic (and for perfectly valid reasons) Coetzee rather avoids answering the question that he originally posed, about whether Bach ‘spoke to him across the ages’ or whether he, Coetzee, was (unwittingly perhaps) choosing high European culture and the codes of that culture in order to escape his class position in white South African society, and the historical dead-end represented by his immediate environment.

But despite the excellence of Coetzee’s writing and argumentation, I remain puzzled.

Somewhere in his writings, possibly The Curtain – I am away from my library right now and cannot check – Milan Kundera speculates on the kind of reception that would be given to a work of Beethoven’s were it written by a contemporary composer and performed as though it were a new composition. Kundera asserts that such a piece of music would be subject to ridicule. No one would take the music or its composer seriously. Since all cultural artefacts are a product of their historical and cultural moment, a ‘contemporary’ writing of the opus 111 piano sonata by a modern composer would fail to have the effect on a latter-day John Franklin, or by extension, on you or me.

How does this play out in relation to Coetzee’s adolescent experience? What if The Well-Tempered Clavier was the work of a brilliant but geeky composer of the 1950s who despised the tendencies of Romanticism and Modernism and elected to write ‘like’ J.S. Bach? The sequence of sounds would be identical, but would the effect be the same? Does this mean that young Coetzee’s response to Bach’s quintessentially classical music had its profound effect– even though he did not know what he was listening to?

How can this come about? Are our responses to music entirely subject to cultural and historic provenance? Is a particular arrangement of sounds only a cipher, a means by which a listener measures him or herself as a participant-observer in cultural experience?

This raises many other questions, including obvious ones such as the way we ditch and discard some music – even find it unlistenable – over the course of years, while other music we can listen to almost any time. But for the moment, Kundera’s question and Coetzee’s musical awakening in 1955 present a paradox that I am struggling to reconcile.

Any comments welcome.

Restless Geography

The blog is founded on the idea that Blanco never spends too much time writing a post, unless it is an article, review or poem that has already been prepared or published elsewhere (i.e. recycled work, of which there is an irregular smattering). In other words the motivating principle is of spontaneity, of always allowing myself, in my writing, to move where the mood takes me, so I do not necessarily end up in a place where I thought I was going: I would go so far as to say that was the whole point of the blog – to begin a thought process and see where it takes me. This will sometimes mean that the title of the piece only makes sense in terms of something that appears towards the end, or is a fleeting thought that arises as a consequence of something in the blog that is not fully explored.

So what we have is a kind of diary, alongside a series of reflections – precisely as the subtitle proclaims – on the mutable universe. Like most things concerning the genesis of the blog, the words came without conscious forethought: but ‘mutable’ is key here: I want the blog to act as an archive – very much in the spirit of the work of my friend, the painter Lluís Peñaranda – of mutability, of fleetingness, of transience. The transience of those things that we explore, and the transience of ourselves.

Actually, the most apt description of what we have is labyrinth. A labyrinth is not only a metaphor for the questing self, and a means of self-transcendence: it is also a way of getting purposefully lost, of going up blind alleys, of plunging deeper into one’s own lack of knowledge and coming back with something unknown, of finding surprising routes to places we never intended going. Of noting that the exit to the labyrinth is sometimes marked Entrance to the Labyrinth.

And of observing what goes on inside the labyrinth when the geography will not stay still.

To be continued.

I set out on a journey, but the geography would not stay still, and I ended up somewhere I hadn’t intended going.

‘Restless Geography’ from Sad Giraffe Café (2010)

A State of Wonder

In Sten Nadolny’s fine novel The Discovery of Slowness, the polar explorer John Franklin attends a recital of Beethoven sonatas on 9th May 1845. During the performance of the opus 111 sonata, “John felt he was actually meeting the fine skeleton of all thought, the elements, and the ephemeral nature of all structures, the duration and slippage of all ideas. He was imbued with insight and optimism. A few moments after the final note sounded he suddenly knew, There is no victory and no defeat. These are arbitrary notions that float about in concepts of time invented by man.”

While it might not be a realistic objective for most of us to achieve this state of immaculate insight very often – supermarket shopping, tax statements, the MOT, and for some of us the basic dignity of finding work, all this stuff gets in the way – we are all gifted these moments of clarity, we all catch the occasional glimpse, and if we are lucky we build up a store of such experiences, an archive of rare encounters with the transcendent. Normally such moments are not instructive to others, nor in fact are they easy to elucidate or express. But cumulatively they create a cluster, form a chain reaction, each epiphany linked mysteriously to all those that have come before, in a steady act of making. I am reminded of the words of the pianist Glenn Gould that I quoted in The Vagabond’s Breakfast: “The purpose of art is not the release of a momentary ejection of adrenalin but rather the gradual, lifelong construction of a state of wonder and serenity.”

Sometimes it swings this way, and sometimes the world has other plans.

Relative Speed

When driving around the country roads of the Ampurdan, one is likely to pass two species of cyclist. The first type travels in groups, is brightly clad in Lycra shorts and shirts emblazoned with the logo of their sports club. They wear aerodynamically designed helmets that make them look vaguely extraterrestrial. They are generally, though not exclusively, white, male and sufficiently well off to own a lot of fancy gear.

The second type of cyclist is solitary, drably garbed in the cast-off clothing of the rural poor, though sometimes he sports hard-earned or fake Adidas or Nike shoes and hoody. He will generally be on his way to, or returning from, a day of menial labour in the fields. At other times he may be sighted rummaging through the municipal garbage and recycling dumps outside local villages. He will be looking for scrap metal, discarded cookers and fridges, even the aluminium from a broken deckchair. This cyclist is invariably African, male

and very poor. He will almost certainly be an illegal immigrant.

The relative speeds at which these distinct cyclists progress along the country roads appears to be in direct proportion to their socio-economic status. The ones who do it as a leisure activity or hobby travel very fast up the winding mountain roads. They are dosed up on multivits and pep pills and nutritive hydrating beverages. On their slick and shiny machines, they push themselves to the limits of sweaty exhaustion. They do this out of choice. They are not going anywhere in particular but are always in a hurry. In other words, their destination doesn’t matter, so long as they get there fast.

The second type of cyclist has a defined and specific destination, but rarely seems in a hurry to get there on his old, recycled machine. He selects a speed best suited to sustain minimum energy loss. The destination matters, and he will get there in as much time as it takes.

An Aleph in my hand

Drove up to the Gers, in France, to visit the brother. It is a four-hour drive in our old Citroën, which starts rattling if required to exceed about 75 mph. It is hot, and the car has no air conditioning, so we leave early. The autoroute up to Toulouse is very dull, but once you get on the B roads west of the city the countryside is fine and lovely, with rolling hills and great fields of sunflower and of maize unravelling to the horizon.

Now maize, or corn, has a special place in Blanco’s heart. For two summers, in 84 and 85, I worked in the maize fields of the Gers on the annual castrage, or castration The picture on the right, incidentally, is of a maize field in Lichtenstein, not the Gers, but one maize field looks pretty much like any other). The odd practice of castration, which was explained to me countless times but which I never fully understood, involves ripping the male part from its socket high on the plant’s stem, and casting it away, which ensures that the next year’s crop will not be contaminated with bâtards, or bastards. Little bastards, or salauds, I used to call them. Back in the day, the work would be done by teams of migrant workers or else down-and-outs like myself eager for a few days work in the fields in convivial company and with good pay. Often the work would come with board and lodging. The Gers is also a wine (and Armagnac) producing region, so there was always plenty to drink. I have very fond memories of those two summers castrating maize, even though the work could be very dull, walking down those interminable rows, ripping out all those male genitals and tossing them away. Of all the most meaningless jobs I have done, the castration is pretty high up on the list. Because of the utter tedium it inspired, I once had a fantasy of discovering an aleph while working on the maize. Of feeling my toes come into contact with something cold and hard and round, stooping to pick it up, and finding I held an aleph in my hand.

Aleph is the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet. An aleph, for those of you who have not read Borges, is a small and miraculous construct that contains within it the entire content of the universe (and all possible universes). Put another way, an Aleph is a point in space that contains all other points. Within it can be seen everything in the universe from every angle simultaneously, apparently without distortion, overlapping or confusion. It is, as you might imagine, incredibly heavy to hold in one’s hand. As you might also imagine, finding an aleph is a pretty rare thing, certainly not an everyday affair. Finding one in a field of maize, then, would have constituted a considerable improvement to the outcome of a day’s work. But it never happened. Maybe, one day, I will have to put it in a book instead. I have however, written a piece about working on the maize, which I reproduce below, with apologies to those who were listening when I said I was not going to use the blog simply to flaunt my own literary creations – Did I say that? Am I imagining it? – but since I am in the Gers this fine Sunday morning, and since Riscle is a real town in this département, I thought I should include it.

Riscle

The maize fields are vast and sad in the wind. The tops of the plants bend unwillingly. I know what happens here. It has always remained a secret until now. But for the sake of friendship I will tell you. In July, the castrators will come. They will rip out the genitals of the male plants, so that the females cannot be impregnated and raise bastards. At least, that is what the locals tell the workers. The real story of the maize is more violent still. Groups of young men and women meet after dark, drink absinthe, and fuck beneath the summer moon. In the morning, tired and spent, they retire to the Café D’Artagnan for coffee with milk and croissants. They are recruited by farmers, who drive them to the maize fields. There they begin the tedious task of le castrage. The young men begin to feel uncomfortable with this de-seeding of the male plants. Their discomfort translates into physical symptoms: aching sides, persistent headaches and vomiting. Later they will complain of spontaneous ejaculation, green sperm, and will participate in outbreaks of frenzied violence towards other males. In early spring the babies are born: little maize-people, with an obsolete immune system inherited from Aztec forebears. The babies all die before July, when the castration begins again.

From Sad Giraffe Café (Arc, 2010)

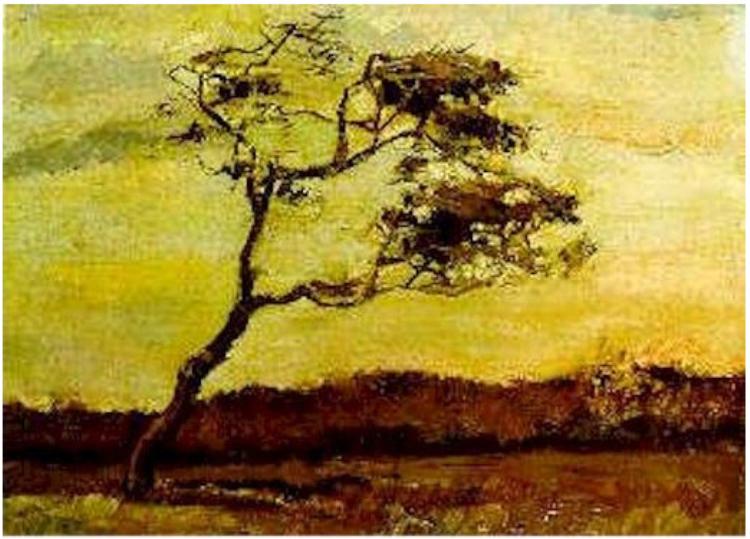

The Wind

There is a wind here called the Tramuntana, which swirls down from the Pyrenees. There is no end to the wind, though there is a discernible beginning to it, that is, there have been days before the wind: Monday for the sake of argument. Or Thursday. The wind had been before, and then gone, after having stayed for an eternity, after having evoked the kinds of comments that we hear when it is around, comments that resound with the lifetimes and inherited memories of a people inundated with this mountain wind. And though we know that it will go away (or die down, or diminish, or seep into the masonry, the woodwork, the skin, the pores, the cell structure) the wind is so much an article of the present moment, of the now, that there is little sense in considering a prospective time of no-wind. Stillness is a remote memory, and cannot really be conceived of during days of wind. It spends these several days infiltrating every corner, becoming absorbed in our furniture and in our minds and bodies: it acts like a swirling incubus, growing inside each perception, every mundane act, and takes them over utterly. So that my knowledge of these crooked olive trees will change; my understanding of the cypresses become distinct; as will the silent apparition of the postwoman at the doorway, of the dead fox lying by the roadside elm, and of my own reflection in the mirror. The truth is, I feel diminished by the eventual departure of the wind. It takes a part of me with it.

Rant

The Rant is in three parts:

Firstly: in Spain, the reporting of the riots in England has uniformly emphasised the racial nature of the disturbances. I am not in a position to comment objectively, having only read the reports in The Guardian online and the BBC, in neither of which race has been presented as a dominant theme.

However, yesterday in El Mundo – the Guardian’s sister paper in Spain – I read:

‘Fortunately, in Spain, the social tensions that have erupted in the United Kingdom and France are absent, probably because the underlying racial component in those countries does not exist in our country.’ This is tantamount to saying there is no racism in Spain, which is clearly nonsense, as any social study taken over the past twenty years will prove. Spain is rife with insidious as well as overt racism. Anyone who thinks otherwise is a cretin, or else in denial.

Second: following enthusiastic reports on Facebook, I bought a DVD of the Korean film Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter . . . and Spring before coming on holiday. Actually, I should add that the FB discussion of the film was unanimously approving, emphasizing said film’s transcendent qualities etc. and, not an irrelevance, all the discussants were women. We watched the film the night before last. It goes like this (look away if you don’t want to know what happens): A monk lives with a small boy, his apprentice. The apprentice tortures animals so the monk tortures the boy in order to make him learn about karma. The boy grows to early manhood. A young woman and her mother turn up at the hermitage (set idyllically in the centre of a lake), hoping to find a cure for the girl’s mysterious malady. We know at once what is going to happen: it is in the eyes of the young man and the young woman. I say to Mrs Blanco – unnecessarily, I admit – that the novice monk will shag the girl and she will get better. It was hardly insightful. So, he takes her to his favourite pool (the one in which he tortured animals as a child) and they do it up against a rock, with requisite although not excessive vigour. Miraculously, the young woman is cured.

The young monk can no longer stay with his master. He longs to marry the young woman and live with her in the real world, where they can do what they did in the rock-pool all day long, without having to break off for spiritual exercises. ‘Desire leads to attachment and attachment leads to murder’ says the old geezer, or something similar. But the young man’s mind is made up. He follows his girlfriend out into the real world (Summer). The years pass. The old man is sweeping out his hermitage when he comes across a scrap of newspaper. How did the newspaper get there? No matter, but it does beg a few questions: ‘Man in his thirties murders wife and flees’. Sure enough, his protégé turns up, on the run, looking much the worse for wear, and sporting a scoundrel’s moustache. He weeps and weeps and tells the old geezer that his wife was unfaithful and loved another man, the hussy. The police are in hot pursuit, and arrive at the sanctuary in the lake. The old man hands the murderer over to the police, but first insists that he carry out some penitence, which involves inscribing a very long mantra on the floor overnight. Then, in the morning, off he goes to prison. Next season however he is back, looking not much older (murdering a woman is obviously not a major offence in Korea). In the meantime the old geezer has incinerated himself, so the young geezer becomes the new old geezer, in fact in the film he is replaced by the same actor. You get the picture; eternal return et cetera. Then in ‘Winter’ a woman turns up, her head entirely covered in a cloth, and deposits a baby with the monk, before falling through a hole in the ice on her way back across the lake from the hermitage and conveniently drowning. In the final sequence, the second ‘Spring’, the new little boy is growing up to be as much of a brat as the first one, and we see him setting off to torture a few frogs. And so it goes.

‘This is one of the very few films which has a real spiritual dimension; it bears that dimension lightly, and persuasively transmits a Buddhist conviction that time, age and youth are an illusion. A charming and rewarding film” writes Peter Bradshaw in The Guardian. “A charming and rewarding film . . . delightful, meditative, serene and gripping” trills another Guardian review; “A work of transporting beauty”, says The Times; “Thoroughly enjoyable and magical” goes the Sunday Mirror.

What a pile of dross. Why do we continue to be sold this kind of Art Film as though it were ‘spiritually uplifting’, when it is simply medieval, repressive, misogynist tripe of the kind that religious fundamentalists have been flogging forever and are flogging still? We hang onto a bizarre fantasy in the West that Buddhism is exempt from this kind of attitudinizing. Moreover, the film is neatly packaged, beautifully shot – and because it is ‘exotic’ everything else – content, dialogue, moral compass, is excluded from judgement.

As far as I could tell the moral of the story is threefold:

1) female illness can normally be cured by male sexuality (aka: a ‘proper seeing to’)

2) men who wish to follow a ‘spiritual path’ will only ever meet with trouble and strife from women, so it is much healthier for the men concerned if the women are a) murdered, or b) fall into holes in the ice.

3) all these things can happen without any qualms so long as they take place in an exotic setting, reflect ‘local’ religious or cultural values and have an ‘uplifting’ or ‘spiritual’ message, and are thereby exempted from the critical criteria we would normally apply to any home-grown cultural artefact.

Third: In August the dogs in this village bark most of the day, and all night. Normally I am oblivious to this, but last night I was not. Last night it drove me to distraction, and eventually, to sleeplessness. It begins as a single, righteous statement of self-assertion on the part of some bonzo, but within seconds he is contested by another, who thinks he can bark louder than the first. A third joins in, invariably some yappy specimen who cannot really compete with the first at all, but has half a mind to follow on the heels of the second woofer . . . and so it goes in a spasmodic but inevitable crescendo. Before long there is total bloody cacophony as terrace after terrace explodes in a fury of barking, and I get up, scribble down something on a notepad which in the morning will be unintelligible, take two tramadol, or two diazepam, or two of whatever is going, and return to bed. Or else just sit on the roof, as I did last night, and watch the waxing moon.

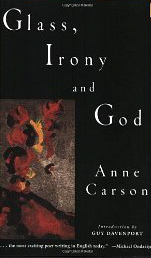

The Glass Essay

This morning, with the first light, I read Anne Carson’s long poem The Glass Essay, 38 pages and not a word wasted. Now every line feels engraved in my consciousness. What a rare occurrence this is. I sit up in bed, propped by a few cushions. Bed is a euphemism. We haven’t got around to buying a bed, in seven years. A mattress on the wooden boards, and a view across red rooftops to the bell-tower of the church. Early swallows skimming and diving. From time to time, while reading, I drift off, and occasionally it happens that I dream the words I have been reading, only to waken and find they are not the words on the page at all, but my own. So, reading Carson’s poetic discourse on Emily Brontë I drift into a dream where I am at the northernmost point of the north of a northern territory. Then I wake and continue to read. That way, reading is even more than usually a kind of collaborative experience.

This morning, with the first light, I read Anne Carson’s long poem The Glass Essay, 38 pages and not a word wasted. Now every line feels engraved in my consciousness. What a rare occurrence this is. I sit up in bed, propped by a few cushions. Bed is a euphemism. We haven’t got around to buying a bed, in seven years. A mattress on the wooden boards, and a view across red rooftops to the bell-tower of the church. Early swallows skimming and diving. From time to time, while reading, I drift off, and occasionally it happens that I dream the words I have been reading, only to waken and find they are not the words on the page at all, but my own. So, reading Carson’s poetic discourse on Emily Brontë I drift into a dream where I am at the northernmost point of the north of a northern territory. Then I wake and continue to read. That way, reading is even more than usually a kind of collaborative experience.

I used to write quite a lot of poetry, but these days I find that the effort it takes to ‘make verse’ – as though straining towards a truth more profound or more lasting than the truth of prose – is not necessarily justified, or justifiable. By whom do I mean justified? By what measure justifiable? I do not know, I really don’t. But, mainly, I write prose.

And then how good it feels, and how rare, to sink into and absorb a poem as fine as this one. There are three themes to it: the

aftermath of a love affair between the narrator and a man she calls Law (he has his echo in her therapist, a woman called Dr Haw), a theme which constitutes the near past. Then there is an account of the life of Emily Brontë, author of Wuthering Heights (the distant past). Finally, the poem is cast in a present tense in which the poet (or narrator) is paying an extended visit to her mother, who lives on a moor in ‘the north’. The majesty of the poem is the way in which Carson threads the three narratives in and around one another, guilefully working each one so as best to extract the full flavour of the other two. There is such skill (and yes, it does appear effortless, which means it was hard-earned) in the composition of the poem. I stand in awe of this writing. To give some impression of the quality, here are three short passages from a single page:

‘When I was young

there were degrees of certainty.

I could say, Yes I know that I have two hands.

Then one day I awakened on a planet of people whose hands

occasionally disappear –’

also:

‘It is stunning, it is a moment like no other,

when one’s lover comes in and says I do not love you anymore.

I switch off the lamp and lie on my back.’

also:

‘Emily had a relationship on this level with someone she calls Thou.

She describes Thou as awake like herself all night

and full of strange power.’

Earlier in the poem she writes:

‘I have never liked lying in bed in the morning.

Law did.

My mother does.

But as soon as the morning light hits my eyes I want to be out in it –

moving along the moor

into the first blue currents and cold navigation of everything awake.’

I too like to be awake at first light, but some days it is good to lie in with it, and read poetry as good as Carson’s.

‘The Glass Essay’ appears in Glass, Irony and God, published by New Directions (1995).

Naked Man with Pit-Bull

Imagine my surprise yesterday, when visiting one of our favourite beaches with friends (where I intended doing a little underwater  fish-gazing with mask and snorkel) I spied a naked man washing his pit-bull in the shallows. Bending over it, lovingly washing its flanks in the plankton-rich waters of the western Med.

fish-gazing with mask and snorkel) I spied a naked man washing his pit-bull in the shallows. Bending over it, lovingly washing its flanks in the plankton-rich waters of the western Med.

This is not a nudist beach, and while I have no objections to nakedness in principle, I do believe it has its proper place in civilized society. I know that many people think differently and they are entitled to set up their own recreational centres where nudism is de rigueur and you can even spend your summer holiday in such places, renting a chalet or a luxury apartment, surrounded by other nude persons. You can go shopping in the site supermarket with nothing on, and sit in the bar bollock-naked sipping your evening cocktail. Michel Houellebecq, once known as the enfant terrible of French Literature (and actually quite a decent poet, as his recent collection ‘The Art of Struggle‘ impressed on me) has written about such places at tedious lengths in his fiction.

But on a regular, costumed beach, it is my belief that bathers should wear a swimming suit. I have no particular objection to bikini tops being removed, but even that is probably only a matter of having become accustomed to it over many years. In the final analysis, I do not mind too much about public nudity either way, and it is really not my business what consulting adults prefer to do. But to have fully grown men parading with all their tackle hanging free, when there are young children roaming the sands around them peering inquisitively at the exposed genitalia, is – while filled with comic potential – not a vision I relish or one in which I wish to share. Nor are beer bellies and sagging tits, and heaving folds of cellulite, but here again I might stand accused of some kind of aesthetic fascism, and should probably stop there.

So, gentle reader, rather than offend your sensibilities by showing the perpetrator of this act of aggressive nudism (who I suspect was French), I have appended a picture of the stretch of beach an hour or so after he had left.

Personally, I like donning mask and flippers and swimming down, peering beneath the surface of the sea, at the underwater flora and rock formations, the hundreds of brightly coloured fish, starfish, octopi and the many other wondrous sights so gloriously described in the films of the late Jacques Cousteau.

PS Mrs Blanco has pointed out that this comes across as a rather pompous and stuffy post. I think, therefore, that I cannot have conveyed my point about the man with the pit-bull very well. To be blunt, there was something fishy about both his ostentatious nudity and the manner in which he washed his dog, as if, not to put too fine a point to it, he were accustomed to more intimate relations with the beast. I find it hard to put concisely: but there was an insalubrious quality to his washing of it that had to be observed in order to be appreciated.

And finally, as Alessandra has pointed out, dogs are not allowed on Catalan beaches in the summer. A fair point.