Cities and Memories

Variations on a theme by Calvino

When a man drives a long time through wild regions, his imagination begins to wander. No, that’s not right. Try again. When a man drives across the last continent at night, from south to north, he must pass the mountain plateau of Omalos. Oh please, not that. Once more? When a man drives a long time across the dry plains of Thrace, he begins to wonder at the migrations that have marked this wretched zone. Turks, Bulgarians and Greeks, with varieties of cruelty and facial hair, wielding curved swords at one another’s throats for centuries. Forced expulsions, exterminations, and the underlying terror that who you are, or who they say you are, is all a terrible mistake, merely circumstantial. And why, for that matter, are you not someone else? If only – you conjecture – I were someone else, and belonged to a different tribe, had a different shaped moustache or nose, the smallest detail of appearance and accent that matters beyond the value of a life. The Levant’s legacy, never yet resolved: Greek, Turk, Arab, Jew. I want to be friends with everyone, and yet know I must have enemies too, if only in order to maintain my friendships. What kind of crazy thinking is that? Salonika, Smyrna, Alexandria, Beirut. We edge into new territories, in which boundaries are differently conceived and yet still intact. How do we progress from here, to the next point, the next dubious epiphany? I feel at once as though we have been witness to a slow disembowelling, over many centuries.

First published in Poetry Review, Summer 2013.

© Richard Gwyn

Dubious categories

In Agota Kristof’s wonderful novel The Third Lie, Claus – or is it Lucas, his anagrammatic twin (the two central characters are indissoluble, or aspects of one and the same person) – spends his nights writing in a notebook. One day, his landlady asks:

“What I want to know is whether you write things that are true or things that are made up.”

I answer that I try to write true stories but at a given point the story becomes unbearable because of its very truth, and then I have to change it. I tell her that I try to tell my story but all of a sudden I can’t – I don’t have the courage, it hurts too much. And so I embellish everything and describe things not as they happened but the way I wish they had happened.

After writing a book of creative nonfiction (I love the way a genre is defined by what it is not – as though ‘fiction’ were somehow the default mode of prose writing), one rather smug person of my acquaintance informed me that he had enjoyed the memoir, but had not been so taken by the fictional parts.

Were there fictional parts? I asked. Oh yes, this keen critic observed, of course there were.

Needless to say, this got me wondering. I could have retorted by quoting Joan Didion, who once wrote:

“Not only have I always had trouble distinguishing between what happened and what might have happened, but I remain unconvinced that the distinction, for my purposes, matters.”

Or I might have cited Gabriel García Márquez:

“Life is not what one lived, but what one remembers and how one remembers it in order to recount it.”

The point is, there is a fine distinction between the literalism of ‘what really happened’ – which is in any case not provable – and the way in which I happen to remember, conjecture and write. Does it simply boil down to a distinction between ‘true things’ and ‘things that are made up’? That seems horribly reductive. What about all the stuff that happens in between?

In the documentary film Patience, Christopher MacLehose tells an anecdote about the publication of Max Sebald’s Rings of Saturn. Sebald was required to state what category of work the book should be shelved under – a standard requirement made by booksellers, and he was dismayed that he had to choose a category: did he want the book filed under biography, history, apocalypse studies, memoir, travel or fiction? – All of them, he said, all of them.

Thinking Pig

Stories of animal transformation abound in myths and folktales across the world. The theme is one that pervades Greek and Celtic mythologies, to take just two examples, and traditionally takes two forms: the ability of a god or sorcerer or shaman to wilfully transform him/herself into an animal; and the punitive transformation of people into animals for some misdeed or crime.

In a reading of Kafka’s Metamorphosis we might argue – as Nabokov does in his lecture notes on the book – that before the actual transformation, Gregor Samsa already lived like an insect, always scuttling about and kowtowing to greater pressures such as familial guilt and responsibility as well as a servile sense of duty to his job. Just as bugs mooch about, busying themselves yet at the same time achieving nothing, Gregor scuttles through his day, occasionally running across another insect and eating morsels as he finds them.

But what of the broader, mythical background to the notion of metamorphosis? In The Odyssey we encounter Proteus and Circe. Proteus changes forms several times throughout the poem: lion, serpent, leopard and pig, and ultimately is the character responsible for guiding Odysseus home. Circe’s ability to transform Odysseus’ crew into pigs might be regarded as the forerunner of countless tales of human-animal metamorphosis.

A powerful motif running though both Irish and Welsh mythic literature is that of shape-shifting . . . In the Welsh narratives, shape-shifting is generally presented as punitive rather than voluntary: a few episodes revolve around the transformation of people into animals because of some misdemeanour. Thus in ‘Culhwch and Olwen’, Twrch Trwyth – an enchanted boar – is the object of one of Culhwch’s quests to win the hand of Olwen. When questioned as to the origin of his misfortune, Trwch Trwyth replied that God blighted him with boar-shape as punishment for his evil ways. In the Fourth Branch of the Mabinogi, Gwydion and his brother Gilfaethwy are turned into three successive pairs of beasts (deer, wolves and swine) because of their conspiracy to rape King Math’s virgin footholder Goewin (Math needs a footholder – obviously – because he will die if his feet are not held in the lap of a virgin).

The pig seems a popular incarnation for errant humans. In Christian symbology they represent venality and the sins of the flesh. But there is more. In Edmund Leach’s famous paper on animal categories and verbal abuse, we are reminded that what we eat is often analogous to whom we are normally expected to sleep with: for instance we don’t – in British culture – tend to eat dogs, and – analogously, according to Leach – we disapprove of incest. We do however eat domestic farm animals (pigs, sheep, chickens etc), which are bred for human consumption, a class of animal that Leach correlates to an intermediate rank of sociability: people whom one might meet socially, within a circle of acquaintances, and who serve as potential sexual partners. By extension, claims Leach, we don’t, as a rule, sleep with complete strangers (questionable, but let’s stick with the theory for a minute) – and accordingly we do not habitually eat exotic animals such as lions and crocodiles and elephants and emus (availability is an issue there, which kind of upsets the theory, but let’s not be pernickety). Leach’s thesis could be summarised in less scholarly terms as the edibility : fuckability theory.

Having just read Marie Darriussecq’s Pig Tales, the English translation of a book originally published in French in 1996 as Truismes, I will concede that pigs are not regarded favourably. The protagonist of this excellent short novel has the misfortune to find herself metamorphosing into a sow and there is little she can do about it. She puts on weight in all the wrong places, her skin turns tough and bristles of hair sprout abundantly. She starts eating flowers and develops a love of raw potatoes. She grows a third nipple, then a full set of six teats. She grunts and squeals uncontrollably and eventually finds it more comfortable to go about on all fours. Darriuessecq’s book is hilarious and filthy and thought-provoking, tackling big themes such as consciousness, gender roles and the objectification of the female body, but it would be a shame to encumber it with too much interpretation. Sometimes a novel can be read like a dream (or a nightmare) and just taken for what it is: a woman morphing into a pig (just as her lover morphs into a wolf). The concept itself is enough to travel with: just think pig. Relax. Lie back in your sty. Make a bacon sandwich. Read a book, why don’t you.

Juan Rulfo and the terror of the blank page

- Juan Rulfo and accomplice.

This morning, after a restless night, I spent a couple of hours picking up books from the shelves around my room, almost at random, dipping into them, dropping them on the floor, where I will find them later and replace them, equally randomly, between new and often unsuitable neighbours. Sometimes I stop and write down a line or two in a notebook, then move on. When I look at the notebook some days from now, I will be curious to know what the point of all this is.

Following a recent discussion about writers who stop writing, and of writers who kill their darlings (see last post, 1 Jan), I start thinking about the Mexican writer and photographer Juan Rulfo, and return, in my grazing, to Pedro Páramo, a brilliant and perplexing short novel, which, on its appearance in 1955 made such a profound impression on the Hispanic literary world, from Borges to Asturias to García Márquez. (Readers of Spanish can find the latter’s account of his discovery of Rulfo’s book here).

I read Pedro Páramo some years ago and return to it now with curiosity, because my memory of it, I discover, is as vague and dreamlike as the book itself.

According to Susan Sontag, in her introduction to the English translation, by Margaret Sayers Peden:

Rulfo has said that he carried Pedro Páramo inside him for many years before he knew how to write it. Rather, he was writing hundreds of pages and then discarding them. He once called the novel an exercise in elimination.

“The practice of writing the short story disciplined me,” he said, “and made me see the need to disappear and to leave my characters the freedom to talk at will, which provoked, it would seem, a lack of structure. Yes, there is a structure in Pedro Páramo, but it is a structure made of silences, of hanging threads, of cut scenes, where everything occurs in a simultaneous time which is a no-time.”

Rulfo’s life, as well as his book, has become legendary. He left behind only around 300 pages of writing; but those pages, according to García Márquez, are as important to us as the 300 or so extant pages of Sophocles – an extraordinary claim, you might think. Rulfo published his books in early middle age (there is a collection of short stories, translated as The Burning Plain, and another short novel, Ell gallo de oro), but for the next 30 years he did not publish anything, although he had taken up photography in the 1940s and continued taking (and occasionally publishing) pictures throughout his life. He was an inveterate traveller, and drinker. He destroyed the long awaited second novel, La Cordillera, a few years before his death at the age of 68 in 1986. Since his death his widow has overseen the publication of his notebooks, and fragments from the unfinished novel, although, as she confesses in her introduction to the notebooks, Rulfo would not have approved, and that she felt she might be doing “something awful” in publishing them.

Juan Rulfo explained his long literary silence in an interview as follows: “Writing causes me to undergo tremendous anxiety. The empty white page is a terrible thing.”

Killing your darlings

For the past few years, whenever people ask me the dread question of ‘what are you working on’ I have mumbled something about a novel called The Blue Tent. The truth is, I have been writing TBT, on and off, since 2006, although the process has been interrupted by other projects, including a memoir and a couple of volumes of translation. However, the writing and completion of the novel has always re-emerged as a pressing need, like an addiction, or (I imagine) a particularly demanding affair with a psychotic lover. I had to get the book done. I needed to have completed another novel (note the pseudo-retrospective quality of this thought). I finished the first full draft in September 2012 and have been revising, when time allows, ever since. The Blue Tent became my secret life. My closest friends even knew it by name, but none of them had read a word of it. I became irritable when not working on it, and fractious when I was. At times I would resort to talking the book up: writing it, I told myself, I would discover what kind of a writer I really was: it would even, after a fashion, make me whole.

The Blue Tent started out as a modern fairy tale about the attempt of an individual to understand the weird and incomprehensible events that begin to overtake his life after a tent appears in the field next to his house. But in the end the activity of writing the novel became contiguous with the inability of the protagonist to act within the story; his torpor began to mimic my own. It was a mess.

Yesterday, in the early hours of New Year’s Eve, I was lying awake, as so often occurs, pondering yet again the structural perversions wrought by the unruly novel, and I realised, after an hour and a half of twisting and turning, that I would have to get up and write things down. This is a familiar pattern. At a quarter to five I made tea, and then ascended to my study in the loft.

But this time, rather than work on the novel, I read through the notes I had made on it over the years and realised that the book was fucked. FUBAR. I didn’t love the story any more; the characters didn’t interest me (and even if they interested other people, I was not inclined to keep working with them); the premise was interesting but essentially it was just an idea that could have been developed in any one of a thousand ways. The way that I had chosen to develop the idea had brought me to a dead end, and I was stuck. The feeling in my gut told me, without hesitation: Stop it, just Stop.

Feeling a little dizzy at the ease with which I had reached this decision (such moments come with the force of a revelation, even if, when you think them over afterwards, the thought has actually been on a slow burn for months, or even years) I googled ‘abandoned novels’ and the first article to come up was Why Do Writers Abandon Novels? – by Dan Kois in the New York Times. It begins as follows:

“A book itself threatens to kill its author repeatedly during its composition,” Michael Chabon writes in the margins of his unfinished novel Fountain City — a novel, he adds, that he could feel “erasing me, breaking me down, burying me alive, drowning me, kicking me down the stairs.” And so Chabon fought back: he killed “Fountain City” in 1992. What was to be the follow-up to his first novel, The Mysteries of Pittsburgh, instead was a black mark on his hard drive, five and a half years of work wasted.”

I felt better already. Schadenfreude. I hadn’t wasted that long. Not five and a half years. Not really. I’d written 60,000 words and done numerous drafts, some of them longer, but Chabon had written 1,500 pages, and was probably working on it full time.

Kois’ article surveys a number of writers’ views and experiences of abandoning a novel – or rather, putting it out of its misery. If something is making your life a misery, “erasing” or “burying you alive”, isn’t it merely an instinct for survival to kill it before it gets you?

Stephen King (as so often) had useful advice on the topic: “Look, writing a novel is like paddling from Boston to London in a bathtub,” he said. “Sometimes the damn tub sinks. It’s a wonder that most of them don’t.”

And then of course, while acknowledging that the book is not turning out as you might have wished – feel it sinking, to follow King’s analogy – you start making compromises with yourself. If you have a publisher and agent waiting for you to deliver, the pressure is on. You begin looking for arguments to convince yourself to let the book go, to just finish it, find a vaguely unsatisfactory resolution (one less unsatisfactory than all the others), publish it – if anyone wants it – and be damned.

But this is not an option. It would plague me forever to let a book go out in that state. While, on the other hand, the sense of liberation that has accompanied the killing of my darling is something to be cherished. This ‘failure’ feels, in fact, nothing like failure at all: it feels like being unchained from a madman.

In the meantime I will take Samuel Beckett’s advice, and learn to fail better next time.

Santa Hemingway

I was walking past this bar, called Revolución de Cuba in Central Cardiff (but seriously), when I spotted this sandwich board on the pavement advertising the venue with a picture of Santa Claus, which on close inspection bore a striking relationship to Ernest Hemingway. The only difference being that rather than bearing the gloomy, withdrawn, rather terrified features of Hemingway’s last couple of years on earth, this guy is looking really cheery. Like Santa Claus, in fact. Except that he’s Hemingway. Maybe.

I wonder how many of the winners of the annual Ernest Hemingway look-alike contest, held in Key West, Florida, actually resemble Father Christmas as much as, if not more than the man who in 1936 battered Wallace Stevens (a man twenty years his senior) to the ground in the rain in that same resort. Stevens, incidentally, did not look remotely like Santa Claus.

Which raises an interesting proposition: rather than have a look-alike contest, wouldn’t it not be more interesting to have an Ernest Hemingway/Santa Claus look-unalike contest? Sticking to males only (for the sake of simplicity) I would nominate Charles Hawtrey. Or Michel Foucault, neither of whom look remotely like the Hemingway/Santa Claus amalgam.

Short story versus novel

Every story encompasses a world. Every story accounts for a series of actions, whether experienced or imagined. The story, if it is any good, also contains within it a substratum, or an undertow, through which the reader is guided towards some underlying truth – or the possibility of a truth. This may consist of a paradox or even a seeming contradiction, but it will, in some way, be traced or suggested by the contours of the outer story.

This notion, at least, can be applied to the short story. When it comes to anything longer I tend to balk. Today on the Guardian website, I read an article about the new novel by the admirable Donna Tartt, a monster of a book at 771 pages, and I recall what Italo Calvino once wrote:

‘Long novels written today are perhaps a contradiction: the dimension of time has been shattered, we cannot love or think except in fragments of time each of which goes off along its own trajectory and immediately disappears. We can rediscover the continuity of time only in the novels of that period when time no longer seemed stopped and did not yet seem to have exploded, a period that lasted no more than a hundred years.’

I don’t know whether or not I entirely agree with this, but the idea of time progressing as a linear continuum does seem to be tied to a social structure where roles (including that of the author) were more fixed, sedentary things. The author proclaimed his (and it was usually a his) authority through texts permeated with the authorial voice, and which sustained that voice, gave it credibility as a constant over a period of calculable time.

And who wants that authority? Not me. Not I, even. Which is why, on days like today, the simple rigour of the short story seems so much more appealing, and far less tiring.

Forgetting Chatwin

Day five of the Wales Writers Chain tour of Argentina and Chile. We began in Buenos Aires on Monday, at the Spanish Cultural Centre, where Mererid Hopwood and I gave lectures on, respectively, the Welsh and English literary traditions of Wales. On the Tuesday, Tiffany Atkinson and myself launched new collections in Spanish, published by the innovative and excellent imprint Gog y Magog – at what might well be my favourite bookshop in the world, Eterna Cadencia. We flew south on Wednesday, to Puerto Madryn, where the first Welsh settlers arrived on the Mimosa in July 1865, and were ourselves received by a small delegation of the Argentine Welsh community, where we were served soft white bread sandwiches, Malbec wine, teisen and tarts in a little hall used for Welsh and cookery classes. Incredibly hospitable and welcoming people.

The tour was organised by the Argentine poet, critic and translator, Jorge Fondebrider along with Sioned Puw Rowlands, and sponsored by various city councils in Patagonia, the ministry of culture of the city of Buenos Aires, Wales Arts International and Wales Literature Exchange. Jorge has christened the tour ‘Forgetting Chatwin’ in refutation of the English author’s semi-fictitious account of Patagonia.

In spite of a heavy schedule of readings, lectures, translation workshops, informal talks, school visits etc, we were able yesterday to have an excursion. Puerto Madryn happens to be very close to the natural reserve of the Valdes Peninsula, so yesterday we travelled along the isthmus to Puerto Pirámide – a charming and dilapidated frontier settlement on the beach – and took a boat trip to see the whales (all of them are the Southern Right Whale, called ‘right’ because of the ease of hunting them in the days of harpoon whaling). The trip to the peninsula allowed us to take a look at the blasted landscape of the interior, the endless bare scrub falling away into the distance under an enormous sky. We passed llama and guanaco – a smaller version of the llama – one of whose characteristic features is the particularly touching way in which the males decide who is to become the paterfamilias. According to our guide, Cesar, the males run at each other and bite their competitor’s testicles, thereby rendering him incapable of reproduction (as well, one imagines, of immediately converting him from tenor to soprano). How terrifying is nature in its simplicity.

And then the whales, which leave me speechless. I heard one sing, truly.

The crew of the Mimosa, from left: Nia Davies, Karen ‘Chuckie’ Owen, Tiffany Atkinson, Jorge Fondebrider and Mererid Hopwood.

Today, more lectures and poetry readings in Trelew, where Mererid Hopwood and Karen Owen will visit a Welsh school, followed by a reading at the University of Patagonia with myself, Tiffany, Karen, Mererid, alongside Jorge Fondebrider, Marina Kohon, Jorge Aulicino (Argentina) and Veronica Zondek (Chile).

Montaigne’s Tower

‘Habit’ according to Samuel Beckett, ‘is the ballast that chains the dog to his vomit’: and it is precisely what Montaigne seeks to uncover and dismantle in his essays. He does this in various ways, but one of his favourites is to run through apparently marvellous and diverse customs from distant cultures in order to convince his readers that what they take for granted is only a matter of what they are accustomed to. As he himself put it: ‘Everyone calls barbarity what he is not accustomed to.’ His essay ‘Of Custom’ discusses, by turn, the question of whether or not one should blow one’s nose into one’s hand or into a piece of linen; how in a certain country no one apart from his wife and children may speak to the king except through a special tube; how in another land ‘virgins openly show their pudenda’ while ‘married women carefully cover and conceal them’; how in other (unspecified) locations the inhabitants ‘not only wear rings on the nose, lips, cheeks and toes, but also have very heavy gold rods thrust through their breasts and buttocks’; how in some nations ‘they cook the body of the deceased and then crush it until a sort of pulp is formed, which they mix with wine, and drink it’; where it is a desirable end to be eaten by dogs; where ‘each man makes a god of what he likes’; where flesh is eaten raw; where they live on human flesh; where people greet each other by putting their finger to the ground and then raising it to heaven; where the women piss standing up and the men squatting; where children are nursed until their twelfth year; where they kill lice with their teeth like monkeys; where they grow hair on one side of their body and shave the other. By blasting his reader with these numerous examples of apparent strangeness, Montaigne makes them question the practices which they habitually regard as unquestionable and normal in a new light. Indeed, he raises many of the issues that cultural anthropology began to tackle four centuries later, and he can safely be regarded as an early relativist. When he had the opportunity to speak with some American Indians from Brazil, the Tupinambá tribe, of which a delegation was brought before the court at Rouen, he was not simply concerned with ‘observing’ them, as though they were rare specimens of primordial life: he was much more interested in recording their amazement at their French hosts. The observers observed.

Why Writers Drink

“An alcoholic may be said in fact to lead two lives, one concealed beneath the other as a subterranean river snakes beneath a road. There is the life of the surface – the cover story, so to speak – and then there is the life of the addict, in which the priority is always to secure another drink.”

Nothing remarkable about this, you might think, except that it mirrors almost exactly what Ricardo Piglia writes about the structure of the short story: that the outer, surface narrative, always contains and conceals a parallel interior story. This is interesting because it poses the extraordinary thesis that a human life is always about (at least) two narratives, the overt and visible, and the covert or hidden. In the case of the addict, the duality of these narratives is especially extreme, because the parallel interior or subterranean story – even if initially concealed or invisible – eventually breaks out into awful visibility, affecting all those in the immediate vicinity.

Even if one takes the subtitle with a pinch of salt, Olivia Laing’s The Trip to Echo Spring: Why Writers Drink, proves a fascinating read, exploring the relationship of six famously bibulous American writers with the bottle. The lives of Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Tennessee Williams, John Cheever, Raymond Carver and John Berryman are put under the microscope and – unsurprisingly – a lot of very messy stuff comes into view. However the book is beautifully written, and displays a profound understanding of both her subject matter and her subjects. Perhaps of all these cases, Fitzgerald’s was the greatest waste, while Berryman, with his astonishing grandiosity, provided the darkest farce. Of Berryman’s final years. Laing writes:

Even if one takes the subtitle with a pinch of salt, Olivia Laing’s The Trip to Echo Spring: Why Writers Drink, proves a fascinating read, exploring the relationship of six famously bibulous American writers with the bottle. The lives of Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Tennessee Williams, John Cheever, Raymond Carver and John Berryman are put under the microscope and – unsurprisingly – a lot of very messy stuff comes into view. However the book is beautifully written, and displays a profound understanding of both her subject matter and her subjects. Perhaps of all these cases, Fitzgerald’s was the greatest waste, while Berryman, with his astonishing grandiosity, provided the darkest farce. Of Berryman’s final years. Laing writes:

“That’s what alcoholism does to a writer. You begin with alchemy, hard labour, and end by letting some grandiose degenerate, some awful aspect of yourself, take up residence at the hearth, the central fire, where they set to ripping out the heart of the work you’ve yet to finish.”

The Trip to Echo Spring: Why Writers Drink is an excellently researched book on a difficult topic. It is filled with fascinating digressions and integrates the author’s findings with a journey she herself undertakes across the United States in pursuit of her subjects’ homes and histories.

Epic poetry and canine aficionados

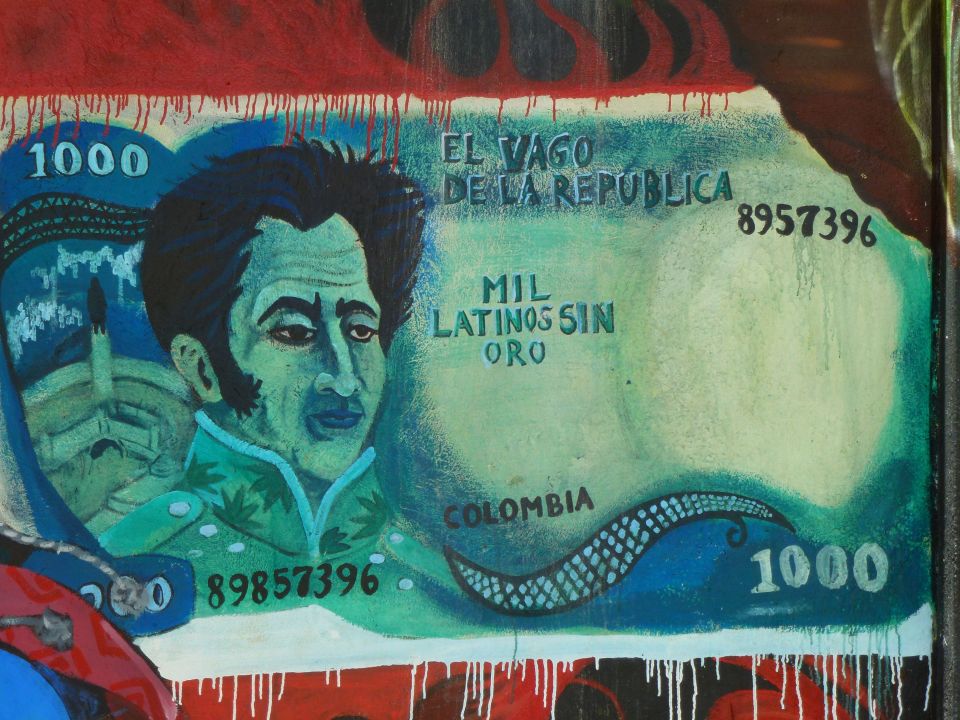

Posting a few pictures as a last offering from my trip to Colombia:

The lettering on the banknote displayed in the wall graffiti suggests that a thousand poor die for each 1000 peso banknote in the idle republic – well, that is one interpretation – and it was displayed in Santo Domingo, once a zone of Medellín riven by incessant gang warfare. Now it is home to a stylish library, designed by the architect Giancarlo Mazzanti and built in 2006-7 with Spanish money (just in time, I guess: there won’t be any more of that coming for a while), which I visited with Jorge and Moya. The people in the library were very friendly and showed us the new theatre. There are lots of places for kids to play intelligent games and read books, but there weren’t actually many kids around, apart from a couple who tried tapping us for money in a playground on the way in.

Below, a solitary canine fan awaits the start of our reading last Saturday morning in the hot and lazy town of Tarso, three hours’ drive from Medellín.

And finally, a photo of the amphitheatre where the main poetry readings took place later the same day. This shot is from the closing recital, where the packed auditorium was composed of over 2,000 listeners of all ages. They sat there in the heat (the readings began at 4 pm) while the poets lurched their way through the marihuana fumes emanating from the audience to read their pomes (sic). I don’t know why, but the applause became louder and louder as the six-hour performance wore on. I’m certain this response had little or no bearing on the quality of the poetry, but it filled my heart with warmth and genuine respect for the Colombian people. After all they’ve been through over the past thirty years, withstanding a poetry recital of such epic proportions surely demands astonishing powers of endurance. I salute them.