In Praise of Coffee

Who first thought to pluck the coffee bean from a tree, dry it, do to it the complicated things that need attending to, and brewing a hot cup of the stuff? Like so many other human discoveries, the odds on this ever happening seem so remote as to defy imagining. I mean, why would anyone bother? And how many horrible concoctions did people try out before hitting on the right one? How many were fatal, and how many caused the ardent experimenter to call out ‘O God, why did I try to smoke/drink that?’ But there seems no lack of ingenuity in humans’ attempts to eat, drink, imbibe, smoke or snort just about every leaf, bean, bark or blossom under the sun. And why not.

I have just opened, and brewed a pot of the sample on the left of the picture, an espresso roast from Las Flores plantation, Nicaragua. It is delicious and strong, but unlike other dark roasts doesn’t leave any nasty metallic aftertaste. I wish I could share a cup with you, although rumour has it that Coffee a Go Go in Cardiff’s St Andrew’s Place have a small allocation, which is their guest bean today.

On my recent trip to VIII International Poetry Festival of Granada in Nicaragua, I retuned with my suitcase laden down (it hit 27 kilos so I had to plant some on Mrs Blanco – has anyone tampered with your luggage madam . . ) not with tomes of poetry (there was some of true value, and I think I got what I needed there) but with a selection of coffee beans. While there, we also enjoyed a tour of one plantation, where we learned, for example, that due to the delicacy of the small sprigs, the coffee beans have to be hand-picked with a gentle downward movement, because if the stems are bent back the wrong way, they will not produce fruit the next year. This is backbreaking and demanding labour, and cannot be carried out recklessly.

I spent several winters in my younger years picking olives, and (depending on the location, and the destination of the olive) this activity can be carried out with varying degrees of vigour, but none of them involve quite such a delicate technique as coffee-picking.

And then there’s the wages paid to the pickers. On most plantations this is minimal – and their living conditions appalling, which is why it is important to try and buy coffee from a responsible source – not easy when half the coffees in the supermarket are labelled under the ambiguous (and almost meaningless) ‘Fair Trade’ label.

A good cup of coffee is a priceless thing, and those beans have made quite a journey. It makes one wonder if there are any decent coffee poems. So I do a search, and am delighted to find there is an entire literature reflecting our love affair with the bean, notably in a site titled, usefully, a history of coffee in literature.

Here is an example, from the little known (early 19th century?) English poet Geoffrey Sephton, extolling the virtues of Kauhee (or coffee) as opposed to those nasty opiates that were all the rage at the time:

To The Mighty Monarch, King Kauhee

Away with opiates! Tantalising snares

To dull the brain with phantoms that are not.

Let no such drugs the subtle senses rot

With visions stealing softly unawares

Into the chambers of the soul. Nightmares

Ride in their wake, the spirits to besot.

Seek surer means to banish haunting cares:

Place on the board the steaming Coffee-pot!

O’er luscious fruit, dessert and sparkling flask,

Let proudly rule as King the Great Kauhee[1],

For he gives joy divine to all that ask,

Together with his spouse, sweet Eau de Vie.

Oh, let us ‘neath his sovran pleasure bask.

Come, raise the fragrant cup and bend the knee!

O great Kauhee, thou democratic Lord,

Born ‘neath the tropic sun and bronzed to

splendour

In lands of Wealth and Wisdom, who can render

Such service to the wandering Human Horde

As thou at every proud or humble board?

Beside the honest workman’s homely fender,

‘Mid dainty dames and damsels sweetly tender.

In china, gold and silver, have we poured

Thy praise and sweetness, Oriental King.

Oh, how we love to hear the kettle sing

In joy at thy approach, embodying

The bitter, sweet and creamy sides of life;

Friend of the People, Enemy of Strife,

Sons of the Earth have born thee labouring.

Should writers reply to their critics?

Should writers respond to their critics? I have discussed this with several writer friends over recent years. The consensus seems to be a resounding No, because once you get involved it is difficult to back out with dignity. If you get a bad review, it sometimes smarts for a while, but you usually get over it. Even people who claim never to read their reviews seem to be remarkably up to date about what others have written concerning their work.

Even a poor review can sometimes contain within it a small gem that can be turned to one’s own advantage. The Times’ disparaging and bitchy review of my first novel referred to the book as ‘superior lifestyle porn’, which we were able to recycle as (sort of) praise. It was OK because lots of other reviewers said very nice things about the book. You learn to take the rough with the smooth. Professional reviewers get paid (usually a pittance, in my experience, but something, at least) for writing their pieces, so should at least take their job seriously. I think it is cowardly and idle not to give a review a thorough evaluation and spend some time on it, rather than just dish out some cheap shots or (as is often the case) string together a few clichés and call it a review.

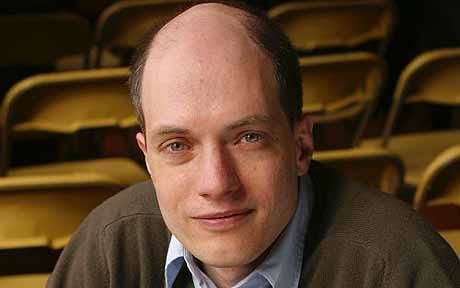

Alas, there is also the serious personal attack, posing as a review, as famously endured by Alain de Botton in the New York Times a couple of years ago.

According to the Daily Telegraph report (I never read the Telegraph, except for the cricket, but I shall cite it in order to make ‘Sue’ (see below) feel justified about her accusations):

The outburst followed a poor review of de Botton’s book The Pleasures and Sorrows of Work, by Caleb Crain in The New York Times.

The author, whose books include Essays in Love and The Consolations of Philosophy, lost his temper during a posting on Crain’s blog, Steamboats Are Ruining Everything.

“In my eyes, and all those who have read it with anything like impartiality, it is a review driven by an almost manic desire to bad-mouth and perversely depreciate anything of value,” he wrote. “The accusations you level at me are simply extraordinary.”

He went on: “I genuinely hope that you will find yourself on the receiving end of such a daft review some time very soon – so that you can grow up and start to take some responsibility for your work as a reviewer. You have now killed my book in the United States, nothing short of that. So that’s two years of work down the drain in one miserable 900 word review.”

The author, who has written widely about the pursuit of happiness, concluded: “I will hate you till the day I die and wish you nothing but ill will in every career move you make. I will be watching with interest and schadenfreude.”

This makes me smile. It is what many of us would like to say, but don’t, because we never come out of it looking well.

Sometimes a review is particularly lazy and ill-informed – not really a review at all – and clearly the writer responsible hasn’t taken the time to read the thing at all, or else is simply a foolish person, a bigot, or a cretin. Or all three.

Which brings me to Goodreads, that democratic website that allows citizens to parade for all to see what books they are reading, what they plan to read, and even what they think of what they have read. Apart from wondering why on earth anyone should care, it seems a perfectly harmless sort of thing to do if you have plenty of time on your hands.

So, to cut to the quick, the other day I came across a ‘review’ of my book The Vagabond’s Breakfast on Goodreads, posted by ‘Sue’ who accuses me of writing ‘middle class poop’.

Let’s consider this accusation for a moment, if only to wonder who among the proletarian hordes – for instance, where I live in Grangetown, Cardiff – would use the term ‘poop’? Surely this critic is giving herself away too easily. But worse than this, she accuses me of writing fiction under the pretext that it is truth, in other words, of being a liar.

Sue’s general gist is that I made some, or all, of the book up, though how she has reached this conclusion, she does not make clear. In a later post – where she has morphed into Redwitch379 – she claims that I myself have said that my book is a ‘fictional autobiography’. Have I? I don’t think so, Sue. So that is galling. And I am thinking up a curse to match de Botton’s. If Sue really is RedWitch379, she had better hang onto her broomstick.

But this is one of the glories – and pitfalls – of the internet. You can hide behind another identity. True, Blanco is a pretty thin disguise, especially as my picture is at the top of the page and most people who comment on this blog seem to know me. The truth is that as well as encouraging a wide-ranging and, at the best of times, stimulating platform for intelligent discussion, websites like Goodreads also allow every fucking idiot on the planet to have a voice, which, of course, is exactly how it should be.

A modest epiphany

From left: John Galán (Colombia), Iman Mersal (Egypt), Frank Báez (Dominican Republic), Tom Pow (Scotland).

Sometimes a short poem hits the mark, for no particular reason, and without providing any easy way of explaining to others the random pleasure it delivers.

I am looking through Postales, an intriguing book of poems by the young Dominican poet Frank Báez – for me one of the finds of the Granada Poetry Festival – and I notice this little gem, a sweetly ironic homage to Ginsburg:

Miaow

I haven’t seen the best minds

of my generation and nor does it bother me.

In the original:

Maullido

No he visto las mejores mentes

De mi generación y ni me interesa.

Great writer = good person? Not on your Nelly.

Is there any correlation between being a great writer and being a good person? I recall reading somewhere in an interview with Borges that he seemed to think that a truly great writer was likely be a good person (without looking too closely at what either of these rather dubious terms actually means).

Not on the evidence of a recent literary event I attended, in which a world-famous and excellent poet showed himself to be a bit of a rotter, and a really dreadful poet, by contrast, turned out to be quite a decent fellow, if a little on the dim side. All this should not surprise anyone. Writers are just like other people, but more so, because nowadays they are expected to be visible in ways that they never were before. This accounts for a lot.

There is also the factor that once a person receives recognition and rewards, they achieve a status that automatically confers a degree of power, and as is well known, power is the most corrupting influence known to humanity.

So no, don’t expect great writers to be good people, in fact the chances are that there is a higher proportion of total shits among them than elsewhere, as so many writers have extraordinarily inflated egos. Which makes it all the more agreeable when you meet an exceptionally good writer who is also a decent person. Fortunately, there are a few of them around too.

In other words, as Bob Dylan frequently reminds us, and I have always maintained, we are all pretty much the same in our differences, whatever our profession or calling, and that power – as we all know – corrupts.

Carnival photos

Here are a few pictures from Wednesday’s carnival in Granada, Nicaragua, where The Tears of Disenchantment (or broken-heartedness) were buried, allegedly.

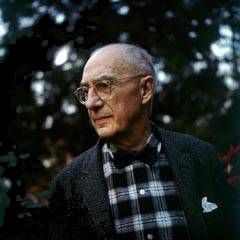

Ernesto Cardenal’s Prayer for Marilyn Monroe

Yesterday I was introduced to one of the great poets of the 20th century, Ernesto Cardenal, on the fragile grounds that I have translated some of his poems, two of which appeared in Poetry Wales last year. There follows a translation of one of his most well-known poems, along with the original Spanish.

Prayer for Marilyn Monroe

Lord

receive this young woman known around the world as Marilyn Monroe

although that wasn’t her real name

(but You know her real name, the name of the orphan raped at the age of 6

and the shopgirl who at 16 had tried to kill herself)

who now comes before You without any makeup

without her Press Agent

without photographers and without autograph hounds,

alone like an astronaut facing night in space.

She dreamed when she was little that she was naked in a church

(according to the Time account)

before a prostrated crowd of people, their heads on the floor

and she had to walk on tiptoe so as not to step on their heads.

You know our dreams better than the psychiatrists.

Church, home, cave, all represent the security of the womb

but something else too …

The heads are her fans, that’s clear

(the mass of heads in the dark under the beam of light).

But the temple isn’t the studios of 20th Century-Fox.

The temple—of marble and gold—is the temple of her body

in which the Son of Man stands whip in hand

driving out the studio bosses of 20th Century-Fox

who made Your house of prayer a den of thieves.

Lord

in this world polluted with sin and radioactivity

You won’t blame it all on a shopgirl

who, like any other shopgirl, dreamed of being a star.

Her dream just became a reality (but like Technicolor’s reality).

She only acted according to the script we gave her

—the story of our own lives. And it was an absurd script.

Forgive her, Lord, and forgive us

for our 20th Century

for this Colossal Super-Production on which we all have worked.

She hungered for love and we offered her tranquilizers.

For her despair, because we’re not saints

psychoanalysis was recommended to her.

Remember, Lord, her growing fear of the camera

and her hatred of makeup—insisting on fresh makeup for each scene—

and how the terror kept building up in her

and making her late to the studios.

Like any other shopgirl

she dreamed of being a star.

And her life was unreal like a dream that a psychiatrist interprets and files.

Her romances were a kiss with closed eyes

and when she opened them

she realized she had been under floodlights

as they killed the floodlights!

and they took down the two walls of the room (it was a movie set)

while the Director left with his scriptbook

because the scene had been shot.

Or like a cruise on a yacht, a kiss in Singapore, a dance in Rio

the reception at the mansion of the Duke and Duchess of Windsor

all viewed in a poor apartment’s tiny living room.

The film ended without the final kiss.

She was found dead in her bed with her hand on the phone.

And the detectives never learned who she was going to call.

She was

like someone who had dialed the number of the only friendly voice

and only heard the voice of a recording that says: WRONG NUMBER.

Or like someone who had been wounded by gangsters

reaching for a disconnected phone.

Lord

whoever it might have been that she was going to call

and didn’t call (and maybe it was no one

or Someone whose number isn’t in the Los Angeles phonebook)

You answer that telephone!

(Translated from the Spanish by Jonathan Cohen)

ORACIÓN POR MARILYN MONROE

Señor

recibe a esta muchacha conocida en toda la Tierra con el nombre de Marilyn Monroe,

aunque ése no era su verdadero nombre

(pero Tú conoces su verdadero nombre, el de la huerfanita violada a los 9 años

y la empleadita de tienda que a los 16 se había querido matar)

y que ahora se presenta ante Ti sin ningún maquillaje

sin su Agente de Prensa

sin fotógrafos y sin firmar autógrafos

sola como un astronauta frente a la noche espacial.

Ella soñó cuando niña que estaba desnuda en una iglesia (según cuenta el Times)

ante una multitud postrada, con las cabezas en el suelo

y tenía que caminar en puntillas para no pisar las cabezas.

Tú conoces nuestros sueños mejor que los psiquiatras.

Iglesia, casa, cueva, son la seguridad del seno materno

pero también algo más que eso…

Las cabezas son los admiradores, es claro

(la masa de cabezas en la oscuridad bajo el chorro de luz).

Pero el templo no son los estudios de la 20th Century-Fox.

El templo —de mármol y oro— es el templo de su cuerpo

en el que está el hijo de Hombre con un látigo en la mano

expulsando a los mercaderes de la 20th Century-Fox

que hicieron de Tu casa de oración una cueva de ladrones.

Señor

en este mundo contaminado de pecados y de radiactividad,

Tú no culparás tan sólo a una empleadita de tienda

que como toda empleadita de tienda soñó con ser estrella de cine.

Y su sueño fue realidad (pero como la realidad del tecnicolor).

Ella no hizo sino actuar según el script que le dimos,

el de nuestras propias vidas, y era un script absurdo.

Perdónala, Señor, y perdónanos a nosotros

por nuestra 20th Century

por esa Colosal Super-Producción en la que todos hemos trabajado.

Ella tenía hambre de amor y le ofrecimos tranquilizantes.

Para la tristeza de no ser santos

se le recomendó el Psicoanálisis.

Recuerda Señor su creciente pavor a la cámara

y el odio al maquillaje insistiendo en maquillarse en cada escena

y cómo se fue haciendo mayor el horror

y mayor la impuntualidad a los estudios.

Como toda empleadita de tienda

soñó ser estrella de cine.

Y su vida fue irreal como un sueño que un psiquiatra interpreta y archiva.

Sus romances fueron un beso con los ojos cerrados

que cuando se abren los ojos

se descubre que fue bajo reflectores

¡y se apagan los reflectores!

Y desmontan las dos paredes del aposento (era un set cinematográfico)

mientras el Director se aleja con su libreta

porque la escena ya fue tomada.

O como un viaje en yate, un beso en Singapur, un baile en Río

la recepción en la mansión del Duque y la Duquesa de Windsor

vistos en la salita del apartamento miserable.

La película terminó sin el beso final.

La hallaron muerta en su cama con la mano en el teléfono.

Y los detectives no supieron a quién iba a llamar.

Fue

como alguien que ha marcado el número de la única voz amiga

y oye tan solo la voz de un disco que le dice: WRONG NUMBER

O como alguien que herido por los gangsters

alarga la mano a un teléfono desconectado.

Señor:

quienquiera que haya sido el que ella iba a llamar

y no llamó (y tal vez no era nadie

o era Alguien cuyo número no está en el Directorio de los Ángeles)

¡contesta Tú al teléfono!

Briefing from Nicaragua

At four in the morning there is a noise of riotous celebration from the nearby square, but I cannot be bothered to make it to the balcony to discover its source. Then there is an hour or so of quiet before the deafening screech of birdsong that signals both the beginning and the end of daylight in the tropics. From the trees circling the park hundreds of birds dance, joust, leap and dive in a frenzied avian fiesta.

Yesterday began with an excursion to the cloud forest volcano of Mombacho – in which we saw howler monkeys

and many birds, including the black headed trogon (trogón cabecinegro, in Spanish) pictured here,

after visiting two coffee plantations, sampling their delicious brews, and witnessing a possum asleep in a bucket

– and concluded with an interminable poetry reading, extremely mixed in quality, but beginning with a single (new) poem by Ernesto Cardenal on the sacking of the museum of Baghdad, and ending with Derek Walcott, again reading a single poem, Sea Grapes. Between these two octogenarian maestros – and with one or two exceptions – a number of distinctly indifferent poets went on for far too long, though I will refrain from mentioning the worst offenders.

Granada is an extraordinary festival, which is growing in importance and recognition, but which needs reining in and the exertion of greater balance in the selection of invited poets. This year, like last, I have met some wonderful individuals, made new friends, and learned a lot, but have also had to listen to far too much bad poetry. Fortunately, Walcott’s Sea Grapes does not fall into this category.

Sea Grapes

That sail which leans on light,

tired of islands,

a schooner beating up the Caribbean

for home, could be Odysseus,

home-bound on the Aegean;

that father and husband’s

longing, under gnarled sour grapes, is

like the adulterer hearing Nausicaa’s name

in every gull’s outcry.

This brings nobody peace. The ancient war

between obsession and responsibility

will never finish and has been the same

for the sea-wanderer or the one on shore

now wriggling on his sandals to walk home,

since Troy sighed its last flame,

and the blind giant’s boulder heaved the trough

from whose groundswell the great hexameters come

to the conclusions of exhausted surf.

The classics can console. But not enough.

Or you can listen to Walcott reading it here.

Brief from Nicaragua

At four in the morning there is a noise of riotous celebration from the nearby square, but I cannot be bothered to make it to the balcony to discover its source. Then there is an hour or so of quiet before the deafening screech of birdsong that signals both the beginning and the end of daylight in the tropics. From the trees circling the park hundreds of birds dance, joust, leap and dive in a frenzied avian fiesta.

Yesterday began with an excursion to the cloud forest volcano of Mombacho – in which we saw howler monkeys

and many birds, including the black headed trogon (trogón cabecinegro, in Spanish) pictured here,

after visiting two coffee plantations, sampling their delicious brews, and witnessing a possum asleep in a bucket

– and concluded with an interminable poetry reading, extremely mixed in quality, but beginning with a single (new) poem by Ernesto Cardenal on the sacking of the museum of Baghdad, and ending with Derek Walcott, again reading a single poem, Sea Grapes. Between these two octogenarian maestros – and with one or two exceptions – a number of distinctly indifferent poets went on for far too long, though I will refrain from mentioning the worst offenders.

Granada is an extraordinary festival, which is growing in importance and recognition, but which needs reining in and the exertion of greater balance in the selection of invited poets. This year, like last, I have met some wonderful individuals, made new friends, and learned a lot, but have also had to listen to far too much bad poetry. Fortunately, Walcott’s Sea Grapes does not fall into this category.

Sea Grapes

That sail which leans on light,

tired of islands,

a schooner beating up the Caribbean

for home, could be Odysseus,

home-bound on the Aegean;

that father and husband’s

longing, under gnarled sour grapes, is

like the adulterer hearing Nausicaa’s name

in every gull’s outcry.

This brings nobody peace. The ancient war

between obsession and responsibility

will never finish and has been the same

for the sea-wanderer or the one on shore

now wriggling on his sandals to walk home,

since Troy sighed its last flame,

and the blind giant’s boulder heaved the trough

from whose groundswell the great hexameters come

to the conclusions of exhausted surf.

The classics can console. But not enough.

Or you can listen to Walcott reading it here.

Burying poverty and misery

The banner photograph at the top of Blanco’s Blog was taken last year in Granada, Nicaragua at the VII International Festival of Poetry, towards the end of a rather hectic afternoon, on which misery and poverty were cast into Lake Nicaragua, encased in a coffin. Whether or not it worked I am yet to see, but am returning to Granada this weekend, with Mrs Blanco, so may find out. I doubt very much whether Daniel Ortega’s re-election as president will have secured the objectives aimed for by the coffin-carrying devils of last year, pictured here by the Scottish poet Brian Johnstone, but next Wednesday, apparently, Las Lágrimas del desamor or the ‘tears of indifference’ will be done away with and buried. We’ll see how that goes.

But to return to the photo on the blog’s banner, a couple of people have pointed out how the black-masked demon pops up behind the three amigos: he is easy to miss, as he seems an integral part of the background. This picture has haunted me for a long time, and I have practically no memory of taking it; everything was happening very quickly, and I certainly didn’t notice the reaper coming up on the left.

The Festival is held every February in the ancient city of Granada, supposedly the first to be built by the Spanish on the American mainland. Poets are invited from around the world: last year over fifty countries were represented by around a hundred poets. My main interest is concerned with a project I have been working on for the past eighteen months: I am putting together an anthology of contemporary Latin American poetry. This year, apart from the many poets from Latin America who will be attending, there are big names from the English-speaking world: Derek Walcott and Robert Pinsky (as well, of course, as my other Scottish compadre, Tom Pow).

More will follow.

The resentment and insecurity of the poet

Pedro Serrano points me towards an article in the current New York Review of Books, about William Carlos Williams. In it, Adam Kirsch mentions Williams’ sense – whether it was true or not – of having been scorned by Pound, and other acquaintances, writing: “I ground my teeth out of resentment, though I acknowledge their privilege to step on my face if they could.” T.S. Eliot comes in for some particularly harsh judgement: “Maybe I’m wrong”, he wrote to Pound, “but I distrust that bastard more than any writer I know in the world today.”

And yet, Kirsch, reminds us, “If you look at the lingua franca of American poetry today – a colloquial free verse focused on visual description and meaningful anecdote – it seems clear that Williams is the twentieth-century poet who has done most to influence our very conception of what poetry should do, and how much it does not need to do.” It might be added that D.H. Lawrence carried out a very similar seminal role in British poetics.

There is much else that is good to think with in this article, some of it coming from Randall Jarrell, an acute reader of Williams, whom he considered “an intellectual in neither the good nor the bad sense of the word.” I think I know what that means, but maybe not . . .

In his autobiography Williams claims that what drove him to write was anger – somewhat like Cervantes – and his anger was clearly kept warm by his self-doubt and insecurity, his dislike or loathing of certain contemporaries (especially Eliot, of whom he claimed, late in life, to be “insanely jealous”) and his fear that he was not considered an ‘important’ poet.

How terrible the tribulations – real or imagined – of the poet, how fragile the music.

Politicians

Politicians are not needed, but they convince us that we need them to resolve the problems which, without them, would not exist.

Fernando Sanchez Dragó

Old Ideas by Leonard Cohen

A new collection of Leonard Cohen songs is a rare event, and Old Ideas, which recycles some familiar themes from the archive, does not disappoint. Throughout Cohen speaks or intones, in his trademark gravelese, not really venturing to follow a tune anymore. Not surprisingly there is a weariness here at times – the guy is 77, after all – reflected in a handwritten scribble in the liner notes: ‘coming to the end of the book / but not quite yet / maybe when we reach the bottom.’ Whether or not this is the last recording by the Magus of Montreal, it has certainly been worth the wait.

If you come to this album expecting all the songs to be of the very highest quality you will be disappointed: they are uneven and the overriding effect is of mood music, Cohen-style, but there are three or four beauties. My favourites are tracks two and three, Amen and Show me the place, in which the singer enacts the role of slave in some religio-sexual psychodrama of the kind we have come to associate almost uniquely with the work of Leonard Cohen. There are also some wonderful, ironic self-references, beginning with the opening lines of the opening song: ‘I love to speak with Leonard / he’s a sportsman and a shepherd’.

‘Amen’ has a familiarity to it, one of those songs you feel you’ve heard before, a song that has always been around . . . I can’t make out whether it is because it bears an uncanny resemblance to a previous Cohen song, and therefore the circling melody and the slow-riding rhythm are so familiar, or simply, as so often with this writer, there is something archetypal in the song itself, as though Cohen were singing from the very bowels of the Judaeo-Christian tradition, brimming over with guilt or nostalgia for things that may or may not have happened. The lyrics alone barely do justice to the slowly churning melody, but I will copy them anyway, and follow it with a clip (unfortunately not from a live performance):

Tell me again

When I’ve been to the river

And I’ve taken the edge off my thirst

Tell me again

When we’re alone and I’m listening

I’m listening so hard that it hurts

Tell me again

When I’m clean and I’m sober

Tell me again

When I’ve seen through the horror

Tell me again

Tell me over and over

Tell me that you want me then

Amen