Poets who translate

It is our last day in Istanbul, and the rain continues, as it has done since Friday evening, shrouding the Bosphorous in grey mist. Before catching a taxi to the airport we snatch a visit to Aghia Sophia, that magnificent evocation of the implausible. The days of translation, of this particular kind of translation, have drawn to an end. Yesterday evening WN (‘Bill’) Herbert, Zoë Skoulding and a certain Richard Gywn, along with our respective translators, Gökçenur Ç, Gonca Özmen and Efe Duyan read our work at the Nazim Hikmet Centre in Kadikö on the Asian side. We went by ferry through the soft rain, a rain almost as comforting as the sahlep we slurped, that peculiar sweet beverage of orchid root, milk and cinnamon, the liquid polyfilla of the Levant, as Bill calls it.

We had an early dinner at Çiya, one of Istanbul’s most successful new restaurants, whose owners have set out to collect recipes from lost corners of Turkey and recreate them in a modest but harmonious three-storey building. I should really say they have translated recipes found on research trips, dug up from family notebooks, dictated by aunts and grandmothers, and have brought them to an Istanbul all too well known for its predictable variations on ratatouille and lamb combinations as a reminder of the glorious culinary past of Anatolia. These recipes have been translated from a time and place distinct from our own, rejecting the universalist culture in which the staple has become ever more dull and tasteless.

It is easy to forget that translation is something we are engaged in, without option and at all times, from the very start of life. It is an activity that is by no means confined to those who term themselves ‘translators’.

Early childhood is the acute phase of translation, and of being translated. Those moments in which every gaze, every enraged instinct on the part of the infant meets with either incomprehension or else with a tentative, and then a more assured translation. Maybe we don’t change that much in this respect, as we continue to translate others, and ourselves, in and throughout the course of a lifetime, with varying degrees of success. The fact that we exist as part of a functioning element within society (family, school, member of this or that group or organisation) consigns us necessarily to different modes of translation.

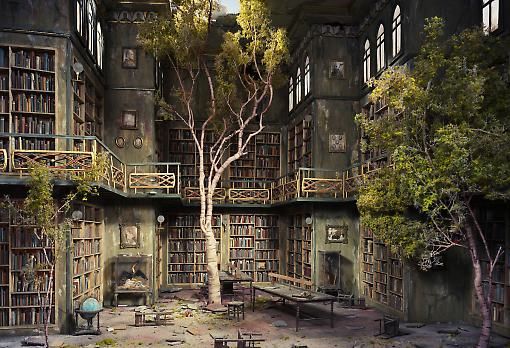

Literary translation concretizes and makes specific acts of translation that otherwise exist in our everyday lives. Poets who also translate join a community of international poet-translators who are enabled, through a process of collaboration, to sharing their respective poetry with new audiences. Many lasting friendships are made in the process, as well as dialogues being opened between cultures in essential and surprising ways.

This is what the organization Literature across Frontiers – under its indefatigable director Alexandra Büchler – manages to such good effect. In meetings across Europe practitioners use a ‘bridge’ language, so that poets who have different first languages but share another language in common (English, most commonly, but any language will do) can combine forces with a native speaker of the bridge language to make new versions of their work. It sounds complicated but it can be a very stimulating process, and it must be said that a lot depends on the individuals gathered together on these occasions, and whether or not they gel as a team. Working as a small unit has other benefits – there are always at least two perspectives – indeed, as many as four or five– on a single poem, and this multiplexity of approach can lead to small epiphanies in the act of translation. Translation is not only a linear and logical progression of a text from one language to another; it is also a process of revelation, an uncovering, de-layering: a transmutation of materials, an act of linguistic alchemy.

Sometimes, needless to say, translation goes all wrong. I have written about this before, in relation to restaurant menus, a constant source of entertainment for anyone who travels. But in the last few days, Istanbul has coughed a few examples of translation weirdness that are equally diverting. I post a selection below.