Brief from Nicaragua

At four in the morning there is a noise of riotous celebration from the nearby square, but I cannot be bothered to make it to the balcony to discover its source. Then there is an hour or so of quiet before the deafening screech of birdsong that signals both the beginning and the end of daylight in the tropics. From the trees circling the park hundreds of birds dance, joust, leap and dive in a frenzied avian fiesta.

Yesterday began with an excursion to the cloud forest volcano of Mombacho – in which we saw howler monkeys

and many birds, including the black headed trogon (trogón cabecinegro, in Spanish) pictured here,

after visiting two coffee plantations, sampling their delicious brews, and witnessing a possum asleep in a bucket

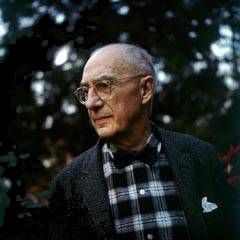

– and concluded with an interminable poetry reading, extremely mixed in quality, but beginning with a single (new) poem by Ernesto Cardenal on the sacking of the museum of Baghdad, and ending with Derek Walcott, again reading a single poem, Sea Grapes. Between these two octogenarian maestros – and with one or two exceptions – a number of distinctly indifferent poets went on for far too long, though I will refrain from mentioning the worst offenders.

Granada is an extraordinary festival, which is growing in importance and recognition, but which needs reining in and the exertion of greater balance in the selection of invited poets. This year, like last, I have met some wonderful individuals, made new friends, and learned a lot, but have also had to listen to far too much bad poetry. Fortunately, Walcott’s Sea Grapes does not fall into this category.

Sea Grapes

That sail which leans on light,

tired of islands,

a schooner beating up the Caribbean

for home, could be Odysseus,

home-bound on the Aegean;

that father and husband’s

longing, under gnarled sour grapes, is

like the adulterer hearing Nausicaa’s name

in every gull’s outcry.

This brings nobody peace. The ancient war

between obsession and responsibility

will never finish and has been the same

for the sea-wanderer or the one on shore

now wriggling on his sandals to walk home,

since Troy sighed its last flame,

and the blind giant’s boulder heaved the trough

from whose groundswell the great hexameters come

to the conclusions of exhausted surf.

The classics can console. But not enough.

Or you can listen to Walcott reading it here.