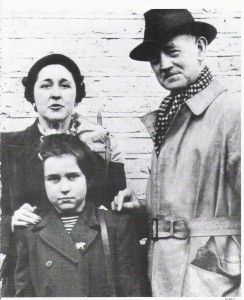

Two weeks ago the Cervantes prize, Spain’s loftiest literary honour, was bestowed on the Chilean poet Nicanor Parra.

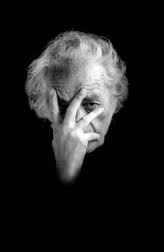

Parra, at ninety-seven years of age, is without doubt the most influential of living South American poets. His career as an eminent physicist (he has been a visiting professor at Oxford and Yale) provided him with a livelihood and immunised him to some extent from the worst abuses of the Pinochet regime. A near-contemporary of Neruda, he considered his more famous compatriot’s poetry to be too flowery, too close for comfort to romantic egotism, and his own ‘antipoetry’ – a term that requires some unpacking – presents a “bleaker vision, prosier rhythms, and starker, surrealist deadpan humor”. By the 1930s Parra was already asserting that what was needed was a vernacular poetry that related to ordinary life and which was accessible to the general public. These ideas, as manifested in Poesia y antipoesia (1954) had a huge impact on poets of a younger generation, especially those who were caught up in the politics of resistance. Parra began writing ‘antipoetry’ because, in his words “poetry wasn’t really working”; there was “a distance between poetry and life”. In a gracious twist, Neruda himself confessed to Parra’s influence on his own later work. It has been claimed, not unreasonably, that Parra’s method derived from his mathematical, relativist background, where he used minimal language and avoided metaphors and tropes in order to address his readers directly. However such assertions almost always sound reductive or cockeyed to me.

Parra’s later work is often a mesh of word association games, intentional cliché and spectacularly straightforward rants about the environment, inequality and corporate corruption. He is a ludic poet, while remaining a poet of intense seriousness. It may well be that his influence will be more lasting than either Neruda or his fellow Nobel laureate, the Mexican Octavio Paz.

Here are a few translations of his work:

OUR FATHER

Our father who art in heaven

Laden with problems of every kind

Your brow knotted

Like any common ordinary man

Don’t worry about us any more.

We understand that you suffer

Because you cannot set your house in order.

We know the Evil One doesn’t leave you in peace

Unmaking everything you make.

He laughs at you

But we weep with you:

Don’t be troubled by his diabolical laughter.

Our father who art where thou art

Surrounded by treacherous angels

Truly: do not suffer any more on our account

You must recognize

That the gods are not infallible.

And that we forgive everything.

(From ‘Bío Bío’)

XXII

CAPITALISM AND SOCIALISM

Nineteenth-century economicrapology

Years before the Principle of Finitude

Neither capitalist nor socialist

But quite the contrary Mr Director:

Intransigent ecologist

We understand by ecology

A socioeconomic movement

Based on the idea of harmony

Of the human species with its environment

Which fights for a ludic life

Creative

egalitarian

pluralist

free of exploitation

And based on communication

And collaboration

Between the big guys & the little guys

MEMORIES OF YOUTH

What’s certain is that I kept going to and fro,

Sometimes bumping into trees,

Bumping into beggars,

I found my way through a forest of chairs and tables,

With my soul on a thread I watched big leaves fall.

But it was all in vain,

I gradually sank deeper into a kind of jelly;

People laughed at my rages,

They started in their armchairs like seaweed carried by the waves

And women looked at me with loathing

Dragging me up, dragging me down,

Making me cry and laugh against my will.

All this provoked in me a feeling of disgust,

Provoked a tempest of incoherent sentences,

Threats, insults, inconsequential curses,

Provoked some exhausting hip movements,

Those funereal dances

That left me breathless

And unable to raise my head for days

For nights.

I was going to and fro, it’s true,

My soul drifted through the streets

Begging for help, begging for a little tenderness;

With a sheet of paper and a pencil I went into cemeteries

Determined not to be tricked.

I kept on at the same matter, around and around

I observed everything close up

Or in an attack of fury I tore out my hair.

In this fashion I began my career as a teacher.

Like a man with a bullet wound I dragged myself around literary events.

I crossed the threshold of private houses,

With my razor tongue I tried to communicate with the audience;

They went on reading their newspapers

Or disappeared behind a taxi.

Where was I to go?

At that hour the shops were shut;

I thought of a slice of onion I had seen during dinner

And of the abyss that separates us from the other abysses.

THE CHRIST OF ELQUI RANTS AT SHAMELESS BOSSES

The bosses don’t have a clue

they want us all to work for nothing

they never put themselves in the shoes of a worker

chop me some wood kiddo

when are you going to kill those rats?

last night I couldn’t sleep again

make water gush from that rock for me

the wife has to go to the gala dance

go find me a handful of pearls

from the bottom of the sea

if you please

then there are others who are

even bigger wankers

iron me this shirt shitface

go find me a tree from the forest fuckwit

on your knees asshole

. . . go check those fuses

and what if I get electrocuted?

and what if a stone lands on my head?

and what if I meet a lion in the forest?

aw hell!

that is of no concern to us

that doesn’t matter in the least

the really important thing

is that the gentleman can read his newspaper in peace

can yawn just when he pleases

can listen to his classical music to his heart’s content

who gives a shit if the worker cracks his skull

if he takes a tumble

while soldering a steel girder

nothing to get worked up about

these half-breeds are a waste of space

let him go fuck himself

and afterwards it’s

I don’t know what happened

you can’t imagine how bad I feel Señora

give her a couple of pats on the back

and the life of a widow and her seven chicks ruined

FROM ‘NEW SERMONS AND TEACHINGS OF THE CHRIST OF ELQUI’

XXXII

Those who are my friends

the sick

the weak

the dispirited

those who don’t have a place to lie down and die

the old

the children

the single mothers

– the students, not because they are troublemakers –

the peasants because they are humble

the fishermen

because they remind me

of the holy apostles of Christ

those who did not know their father

those who, like me, lost their mother

those condemned to a perpetual queue

in so-called public offices

those humiliated by their own children

those abused by their own spouses

the Araucanian Indians

those who have been overlooked at some time or other

those who can’t even sign their names

the bakers

the gravediggers

my friends are

the dreamers, the idealists who

like Him

surrendered their lives

to the holocaust

for a better world

ROLLER COASTER

For half a century

Poetry was the paradise

Of the solemn fool.

Until I came along

And set up my roller coaster.

Go on up, if you want.

It’s not my fault if you come down

Bleeding from your mouth and nose.

Translations by Richard Gwyn, first published in Poetry Wales, Vol 46, No 3 Winter 2010-11.