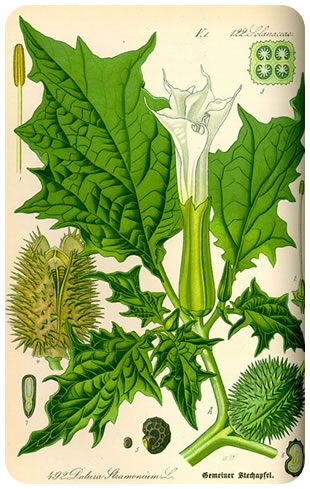

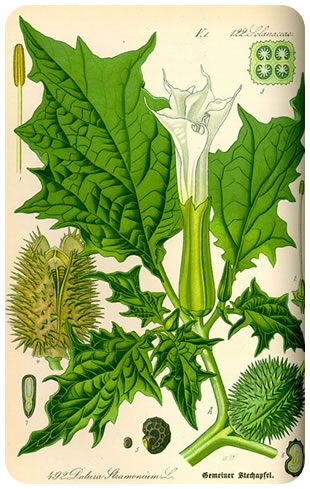

Datura Stramonium

Following a surprise visit yesterday from Iwan Bala, and a moment in which we discussed the profound influence of the Mabinogion stories on both of us, I fell into that state of reflection, or daydream, in which different ideas coalesce or merge. Iwan had mentioned how the ancient Welsh tribes among whom the stories in the Mabinogion emerged – they were part of an oral storytelling tradition long before they were set first down as texts in the eleventh century – sustained a shamanic tradition whose adepts almost certainly used hallucinogens of some kind; magic mushrooms and quite possibly the datura plant, the properties and effects of which I describe in section 29 of The Vagabond’s Breakfast.

Shamans would, in the cultures such as those of the British Celtic peoples of this period, provide the core transcendental experiences on behalf of the tribe, or group, which would involve visions and engagements with the ‘other world’, the place described as Annwn in the Mabinogion stories. Among such cultures the veil between worlds was perhaps not quite so thick as it has since become.

It was brought to my attention by a recent re-reading of Margaret Attwood’s Negotiating with the Dead that among certain indigenous peoples the shamanistic journey follows well-trodden paths, and overcoming an encounter with the ghost-like creatures of the kind I describe in the VB is a not uncommon feature of the Shaman’s necessary accomplishment. I found this strangely reassuring.

But this was not the only adventure that I have recounted in relation to the deadly and secretive datura plant. Another encounter with datura forms the basis of a very loosely autobiographical short story set in Andalusia. Browsing the internet, I find photos of the very deserted village in which the story is set (which I call Las Perdidas) but is actually San Pedro, in the Cabo de Gata peninsular of Andalusia.

The brief for the story was, very broadly, the theme of the handless maiden, a story that has haunted me over the years, and which appears in many versions, perhaps most famously that of the Brothers Grimm, which can be found here. It is a deeply poignant story of female disempowerment, which in my version becomes inverted; that is to say the central female character, Goril, might be a handless maiden – and is most certainly damaged – but she has taken control of her life in the only way she knows, with dramatic and, in turn, damaging consequences.

The story was first published last year in the book Sing Sorrow Sorrow (Ed. Gwen Davies, Seren, 2010). I will post the first part today, and the conclusion tomorrow.

THE HANDLESS MAIDEN

She comes in through the window, where I am enjoying a game of chess on the floor with Callum (there is no furniture in the squat) as though it were the standard way of entering a building, sidling under the half-open wooden frame, and swinging her legs over the sill, before alighting, like a cat, on the wooden floor, within inches of the chess-board. She is wearing very short cut-off denim jeans and a man’s white vest, and she springs across the room towards Ana, who lives in the house, and in whom (without going into unnecessary detail) I have an interest, before the two of them disappear out of the door and along the corridor, to Ana’s room, talking in Norwegian.

Callum (tall, Scottish, a slacker) gazes after the newcomer, admiringly. She looks as if she has emerged from an illustrated edition of Oliver Twist, a saucer-eyed urchin, small and slim, with a mess of short, wheat-coloured hair.

Goril is nineteen, perhaps the most accomplished hustler I have met, and over the next few days, due to her friendship with Ana – they knew each other back in Oslo – I get to see her in action. With her sweet, innocent face, few would suspect that her mere presence in a public place constitutes an immediate threat to any carelessly guarded wallet or handbag, which items, in her company, are likely to vanish without trace. Unlike the other vagrants here in Andalucia, she never begs, nor does conjuring tricks, nor plays a musical instrument, yet she manages to extract money and goods from people with amazing facility; tourists, bar-owners, even, alarmingly, drug-dealers – to the extent that within a week of turning up, she comes to the house one morning with a thick wad of bank notes and offers to take everyone to the seaside. She says she has been given the money by the Norwegian consulate, in order to procure a ticket home before the Guardia Civil incarcerate her for the greater good of the citizenry. I don’t know if she is telling the truth, I don’t even know if there is a Norwegian consulate in Granada, nor do I care. In the idle way that associations are formed and dissolved among vagabonds, she has become a member of our gang, although Goril is most certainly not a joiner.

The place to which we are headed is an abandoned village on a remote and undeveloped outcrop of land jutting out into the Med, east of Almeria. It is called Las Perdidas, which means The Lost Women, and I should have known better than to go there in the first place, but am intrigued by the possibilities. Among which, of course, I include Ana, who looks like a young Björk, and whose feelings towards me are a mystery, due to her apparent reluctance to engage in conversation. There are rumours of natural hot springs and healing mud baths. It sounds like paradise, and as such might provide the ambience for our relationship to blossom.

We take the morning bus to Almeria and have a two-hour wait before our connection. Antonio, along with his friend Pedro, the local boys in our little band, has the idea of buying a yearling lamb, which he acquires off some guy in the nearby market, ready-skinned. Antonio has it wrapped in preserving herbs and sacking for the bus journey to the coast. We have to carry the thing with us, but it’s going to be worth it, Antonio says: this is real food. Goril pays for the bus, the meat, everything.

Las Perdidas, it transpires, is way off the beaten track. The bus stops at a nearby town and we walk along an unsurfaced road for an hour before descending a narrow mule-path down the cliff face towards a jumble of stone cottages near the beach. Some of the buildings look as if they were deserted a century ago and are beyond repair, but others even have roofs, and a semi-permanent settlement of hippies or friquis live in the more robust houses, which are perched at a slight elevation, overlooking the sea. These inhabitants have become accustomed to a drifting population occupying the lower, more ruinous houses, or sleeping rough on the beach, and pay us no attention as we file by, the six of us, carrying our possessions, sleeping bags or blankets, and several plastic containers filled with wine.

When we arrive on the beach, we immediately set about collecting driftwood and scrub for a fire. I make up a search party with Ana, Callum and Goril, and after assembling a small mountain of fuel, we strip off and go for a swim, and although it’s April, the water is not as cold as I expect it to be; perhaps the shape of the cove protects Las Perdidas from cooler currents. Afterwards, Goril stands naked at the water’s edge, vigorously drying herself with a scrap of towel. She suggests we return to the small town where the bus dropped us off, to ‘score some beers and tapas.’ That’s how she talks. Her English, like Ana’s, is fluent, but sprinkled with a gratuitous sampling of time-warped hippy jargon. Perhaps it amuses her to talk this way. The treat will be on her, she says, or rather, on the king of Norway. Long live the King, chimes Callum. Ana, in an unprecedented demonstration of affection, links arms with me. She hasn’t honoured me with one of her rare and random excursions into conversation yet today, but this, at least, is progress. The four of us move up the beach to explain our plan to our Spanish friends.

The beach fire is going strong but will need to burn down before Antonio can start cooking the lamb on his improvised spit, and it’ll be a few hours before the meat is cooked. He and Pedro have a bag of grass and are happy to stay and tend the fire. We have a smoke with them before leaving. By now it’s late afternoon.

We’re on our fourth round of beers when Goril falls into conversation with a young German who is drinking on his own at the bar. He’s a tourist, rather than a traveller. His name is Kurt. He’s predictably blonde and red-faced, but seems friendly enough and a little lonely. Goril buys him a drink and Kurt buys us all drinks in return; in fact we can’t stop him buying us drinks, even if we were inclined to, he seems so happy to have people to talk with in his faltering English. He is staying at the hotel attached to the bar, and has just driven the length of France and Spain, as he tells us, until the land runs out, in order to get over heartbreak with a woman, pronouncing the absurd phrase with such Teutonic sincerity that Callum splutters into his beer (fortunately he is facing me, and Kurt does not seem to notice the indiscretion, although Ana does: she glares at Callum). Travel, says Callum, trying to make amends, in case he has offended Goril also, is a great healer. Travel, and alcohol. Especially alcohol. You are doing the right thing, my laddie. Drink up and forget your troubles. You’re among friends. When Kurt, bewildered by Callum’s accent, enquires of Callum and myself where we are from, he seems delighted by our reply: Ah, the Celtic peoples, he says, this I like. Myself I am a Wandal. From the Germanic tribe, you know, of Wandals.

He beams at us and we smile obligingly. But Kurt is harmless, and generous with his cash, and is obviously enamoured of our blonde Scandinavian talisman, who might be providing him with a glimpse of redemption after his experience with heartbreak woman. So it comes as no surprise that he offers to drive us back along the track in his smart BMW, parking the car where the road ends, and insists on descending with us to the beach at Las Perdidas. The light is fading but the earth is still warm, and there is the edge of a cool breeze from the sea.

The lamb is cooked to perfection, but before we get stuck in, Pedro, who is a connoisseur of plants and wildlife (as well as narcotics) tells us he has brewed a concoction, as an aperitif, he adds, thoughtfully. He seems reluctant, at first, to explain in any detail what is in the drink, but on being pressed, tells us it is made from the hallucinogenic seeds of a plant which grows abundantly in these parts. He passes around a cup filled with the brew. It tastes vile but everyone drinks some; we are a hardened band of psychotropic adepts. When it comes to Kurt’s turn, he looks questioningly at Goril. Pedro has given his explanation in Spanish, which Kurt neither speaks nor understands. Goril nods her head, saying something to him that I cannot hear; and maybe I am the only one to notice this, but she turns towards Ana, and she winks. Kurt knocks back the drink and passes the cup to Pedro to be re-filled. Everyone is in a fine mood. Antonio cuts slabs of flesh from the legs and shoulders of the lamb, and there is more to eat than the seven of us can possibly manage. A young French couple, who live in the hippy colony, venture down to the beach with their baby and attendant mongrel, following the scent of cooking. We tell them to go and get the other hippies, but they say that most of the residents are vegetarian, and would not wish to participate in this carnivorous feast. More fool them, scoffs Pedro. How could anyone resist the gorgeous smell of lamb roasting on a spit? Kurt, having demanded a translation of this exchange, agrees. He tells a vegetarian joke, very badly. He tells us we are a great bunch of guys. We help ourselves from the platter that Antonio has piled high with meat, and tear at hunks of bread and help ourselves to wine, swigging from plastic bottles or squirting the stuff into our faces from the wineskin that Antonio hands around.

Ana, I am pleased to report, is sitting at my side, and she leans close and speaks quietly.

You know, she says, glancing over at Goril, when she was about thirteen, back in Oslo, her father locked her in a room and fed her on raw meat, raw reindeer meat. For three months. And someone found out, a neighbour, he heard her howling like a dog, and called the police. When she got out, and her dad was taken away, she wouldn’t eat anything else, just raw meat.

Hell, I say, and what happened?

She got sick, says Ana.

Is that it? I ask.

Yup, she says, and smiles, pleased with herself for this little foray into anecdote.

I feel a great affection for Ana, but am startled by her story.

Didn’t she have a mother? I ask, didn’t she have someone to look after her?

Ana shakes her head. Her mum died when she was small. Her dad was a junkie. He was very bad news. She grew up on the streets. My mother, she adds, hesitating, said she was a handless maiden.

She did? I ask, curious: why did she say that?

Well, says Ana, it means her father made a devil’s bargain, like he sold her soul. In the story, the girl’s father is a miller and he makes a deal with the devil, because he is greedy, because he wants more grain from his mill, more gold, and the devil cuts off the daughter’s hands and she is left to wander in the forest. That, according to my mum, was what happened to Goril. That’s why she’s the way she is.

I watch Goril for a minute, sitting cross-legged between her admirers, Callum and Kurt. She is eating ravenously. She consumed several substantial tapas not long ago, but she launches into the meat and bread as if she has not eaten for a week.

Although Callum has the hots for Goril, I am pretty certain he will not make the first move, which is probably wise. Kurt, to her left, is picking at his meat between soulful glances at Goril, then looking around to see if anyone has noticed. While I am musing on this tableau, Goril looks up and stares straight at me, as though her radar has picked up on my surveillance. For a split second her eyes spell out an icy, impassive warning, then her face melts into a smile. She makes a little wave at me, fluttering the fingers of her hand, then turns to the French couple and asks them to show us where the mud baths are, the famous mud baths.

(to be continued)