Good Things about Being Welsh: No.1

Walking out yesterday with the brother, daughter and dog, this sign might have taken us by surprise, had we not been Welsh, and therefore accustomed to such wonders. Whether or not Being Welsh is perceived as a blessing in the general run of things, when it comes to going out of a Saturday and walking a country mile, coming across a sign such as the one in my photo – and I assure you it is not a set-up – only serves to remind us of our inordinate good fortune. Consider the topography: a field dotted with sheep; an unmarked road – little more than a lane – overgrown hedgerow and fern; a sky not threatening rain. And a home-made sign pointing up the road, indicating that in this direction the traveller will find a restorative musical experience. In Wales we too are suffering the crisis effected by the bastard bankers, but here, at least, we have fresh duck eggs, border collie pups, a few bags of spuds and a MALE VOICE CHOIR.

Blogging and the Myth of the ‘Real Me’

When you start doing something new, it makes sense to question why you are doing it. I started this blog two and a half weeks ago, a decision made on the spur of the moment, because I had hit a roadblock in a novel I am writing and wanted to create a diversion, or some form of prevarication or distraction – to see if any new ideas else came along, as they usually do. And to keep myself writing, rather than sink into the familiar mire of the pointlessness of everything that even a minor incident of self-doubt is likely to incite.

As if by magical coincidence, today’s news about Google+ insisting on its account holders using their real names coincides with a line of thought I was pursuing even as the news broke.

Thinking about blogging, specifically, and reflecting in more general terms on what we do and why we do it, I was leafing through old diaries, a useful resource for the blogger, and I found notes that I must have scribbled on a long plane trip three years ago. I was reading an article by Michael Greenberg, discussing his friend Lee Siegel, who writes about the Internet (there is another concern here, on the dangers of writing reviews of one’s friends’ books, which I will return to in another post). I discovered that Siegel has made the study of the internet his principal concern, and (as I later found out) for good reason. What he writes is largely dire and depressing: “You’re alone but you’re not alone, projecting yourself onto this screen with all these invisible people there, who, like you, aren’t who they say they are. When you change your identity, your language becomes corrupted. It becomes easier to tell lies. You think you’re chatting with someone, but who is it? As often as not you’re consorting with your own demons.” And there’s more: “it’s a triumph of capitalism . . . people learn to package themselves. They perform their privacy. We want to believe we’re expressing our individuality, but to stand out in cyberspace, to become viral” (he means popular, I guess) “you must be able to sound more like everyone else than anyone else.” Siegel’s book is called Against the machine: being human in the age of the Electronic Mob. The book appears to be out of print already.

Among other useful observations, Siegel is doubtless right in saying that “the Internet is possibly the most radical transformation of private and public life in the history of humankind.” It has caused a thorough reassessment of what it means to be an individual in contemporary culture. However while it is one thing for American or European critics to swing out against the internet and bloggers – and what Siegel sensationally calls ‘blogofascism’ (this tiresome use of ‘fascism’ as a suffix actually distracts us from the truth that genuine fascism – pace Mussolini – is alive and kicking, as recent events in Norway have so tragically illustrated) and the truly significant developments in the Arab world and Iran, in particular, would suggest there are many ways in which the Internet, and blogging, in particular, have provided a crucial link to the wider world when oppressive governments murder and abuse their people, and as a lifeline for individuals facing persecution and discrimination.

Siegel also writes nonsense in relation to TV programmes like American Idol or the X Factor. “Popular culture,” he argues, “used to draw people to what they liked. Internet culture draws people to what everyone else likes.” I would argue that the forces of capitalism that direct and control ‘popular culture’ have always worked on the principle that people are drawn towards ‘what everyone else likes’. My brief stint in the world of advertising would have taught me that, over three decades ago, if it hadn’t been bloody obvious anyway.

Siegel’s comments on the internet and blogging take on a different cast when one reflects that he was suspended from his job as correspondent for The New Republic when it was discovered that while working for the magazine he was posting commentaries – in the name of his alter ego, called ‘sprezzatura” – referring to his own (Siegel’s) brilliance. Does the phrase ‘consorting with your own demons’ ring a bell here? He specifically denied being Siegel when challenged by an anonymous detractor in the magazine’s feedback section. And (here I am relying on his Wikipedia entry) in response to readers who had criticized his negative comments about a well-known American chat-show host, Jon Stewart, ‘sprezzatura’ wrote, “Siegel is brave, brilliant, and wittier than Stewart will ever be. Take that, you bunch of immature, abusive sheep”.

There seems to be some justification, then, for his asking: “You think you’re chatting with someone, but who is it?” and to pose that tired old cliché about ‘our real identity’. Besides, what is this ‘real me’ that American cultural critics and self-help writers throughout the world are so hell-bent on revealing – and which the Internet is attributed such terrible powers in concealing? Actually there will always be a minority (predatory paedophiles, racists etc) who will abuse any system where greater freedoms of movement and communication are taken as a right: it is one of the defects of living in a modern democratic society (viz. recent events in Norway, again). But would we be prepared to sacrifice those freedoms for the sake of a few sick individuals?

Returning to Siegel and his attack on blogging, hasn’t he got all this about our ‘real identity’ a bit wrong? Having had his own mask pulled off, he wants no one else to have one, like a spoiled brat whose party prank went adrift. What is wrong with the wearing of masks? All of us do it all of the time, constantly removing and replacing masks at social events, in different relationships, even within the course of a single conversation. Not one of us remains intrinsically the same organism for very long, and besides, every cell in our body is routinely replaced, so that within a periodic span you are actually composed of distinct molecular matter. It is not necessary, as Western culture dictates (particularly in its insistence through religion and, subsequently, through psychotherapy) to be constantly striving to discover who is the ‘real me’ behind the mask: sufficient that we live a shifting, amorphous sequence of roles, one often leading into another, one more appropriate to a particular setting than another, but none of them in place merely to obscure something else, none of them out to prevent the ‘real me’ from struggling free in some kind of monotheistic melodrama in which the individual is God, and in which truth is absolute and inviolable. So I am happy to be Ricardo Blanco, even if at times he merges with the person known as Richard Gwyn. But Blanco also reserves the right within that broad persona (the Latin for mask) to give expression to his love of play and of carnival, to reveal from time to time his countless others, to give them free rein upon the earth, to send them forth to multiply merrily in the vaunted and limitless pastures of cyberspace.

How to talk about books you haven’t read (and how to write like Kafka)

I wake up early, make tea, return to bed, and start reflecting on the many, many books that I have not read, that I will in all probability never read. In an attempt to console myself (not that I am really all that bothered), I recall Pierre Bayard’s highly entertaining How to talk about books you haven’t read, which I always recommend to students at the university. It was a significantly more rewarding read than the title might suggest. And as for the techniques of reading a huge amount at speed: why bother? Unless, of course you are judging some competition and are required to read ninety novels in a month, in which case I have heard it is a good idea to read the first two chapters and the last, and if they are promising, to read the bits in between. In fact that might be a good attitude to apply to all fiction reading: It is horrible being caught up in a novel that you don’t want to be reading – in fact there are a thousand things you would rather be doing – but you somehow feel obliged to finish. The last time I had that experience was with Martin Amis’ The Pregnant Widow, which I thought quite dreadful, but out of some obscure sense of obligation, perhaps for once having enjoyed Money – I plodded on like an earnest foot-soldier to the bitter end. And then I decided: no more. No longer will I make myself finish the long book that is boring me to tears. So Bayard’s advice is well heeded. If you want to find out more, read his book. Besides – returning to my original line of thought – no one has read everything, not even Borges. But that needn’t stop you talking as if you had, according to Bayard, at least.

That there are so many books in the world would indicate that there is a lot to write about, but this does not always seem to be the case for the aspiring writer. Undergraduate students at the university where I teach often complain of not having anything to write about, by which they mean that their resources are limited by age and experience (a bit like applying for your first job). One way around this is to heed the advice given by Kafka, that “you don’t sit in your room and set out to write a story; if you just wait for it to happen, it will”. This might have been the way it was for Kafka: it certainly doesn’t always work with my students. But hang on (I hear you say) – where and when did Kafka say this? I have just lifted it from my notebook, because on 18th June, following my appearance with the delightful and hilarious Sandi Toksvig on Excess Baggage, I pootled along to the British Museum, where the London Review of Books was hosting a series of talks on World Literature. I walked in on a session with the Galician novelist Manuel Rivas, and the scribble in my notebook can be attributed to him. What he was attempting to summarize, from Kafka’s notebooks, was this: “You need not leave your room. Remain sitting at your table and listen. You need not even listen, simply wait, just learn to become quiet, and still, and solitary. The world will freely offer itself to you to be unmasked. It has no choice; it will roll in ecstasy at your feet.” Which is rather different, but probably still of not much help to my students, who would willingly beg, borrow, or steal their £9k a year fees to have anything rolling in ecstasy at their feet. What student writers regularly misunderstand is that they have to actually start writing before the ideas happen: they will arrive at the ideas through the practice of writing. Ideas don’t necessarily always ignite the writing: the writing can ignite the ideas. That’s why I always recommend them to just start writing, anything, freewriting or even nonsense, just to get into the swing of it, and then, with luck, the ideas will come.

Rivas came up with another quotation that I have no means of verifying, from Claude Lévi-Strauss, whom I last studied in any detail as a student at the LSE many years ago. According to Rivas, L-S said that in Greek times people and animals shared the same earth. Which I liked enough to jot down in my notebook also (they are the only two jottings from the Rivas talk). I love the idea of people and animals sharing the earth in respectful harmony, and for that reason have chosen a picture by Franz Marc to head this entry, Marc had a keen sensibility to the animal world, and was famous for going everywhere with his large white dog.

As a postscript, Mrs Blanco was a little concerned that I may have given the impression in my blog of 24th July that she did not think I was passionate. To set the record straight, this is neither the impression I meant to give, nor is it the opinion that she holds, and would add that a love of books is by no means incompatible with a passionate nature.

And finally, living proof that, as Goethe said, by simply making the effort to do something, the forces of providence will begin to move with you (or something like that) I find – while on my search for the correct wording of the one about sitting in your room and waiting, another quote from Kafka’s diaries for all aspiring bloggers (who are the diarists of our era), from February 25, 1912: “Hold fast to the diary from today on! Write regularly! Don’t surrender! Even if no salvation should come, I want to be worthy of it at every moment.” Huzzah!

Who do we think we are?

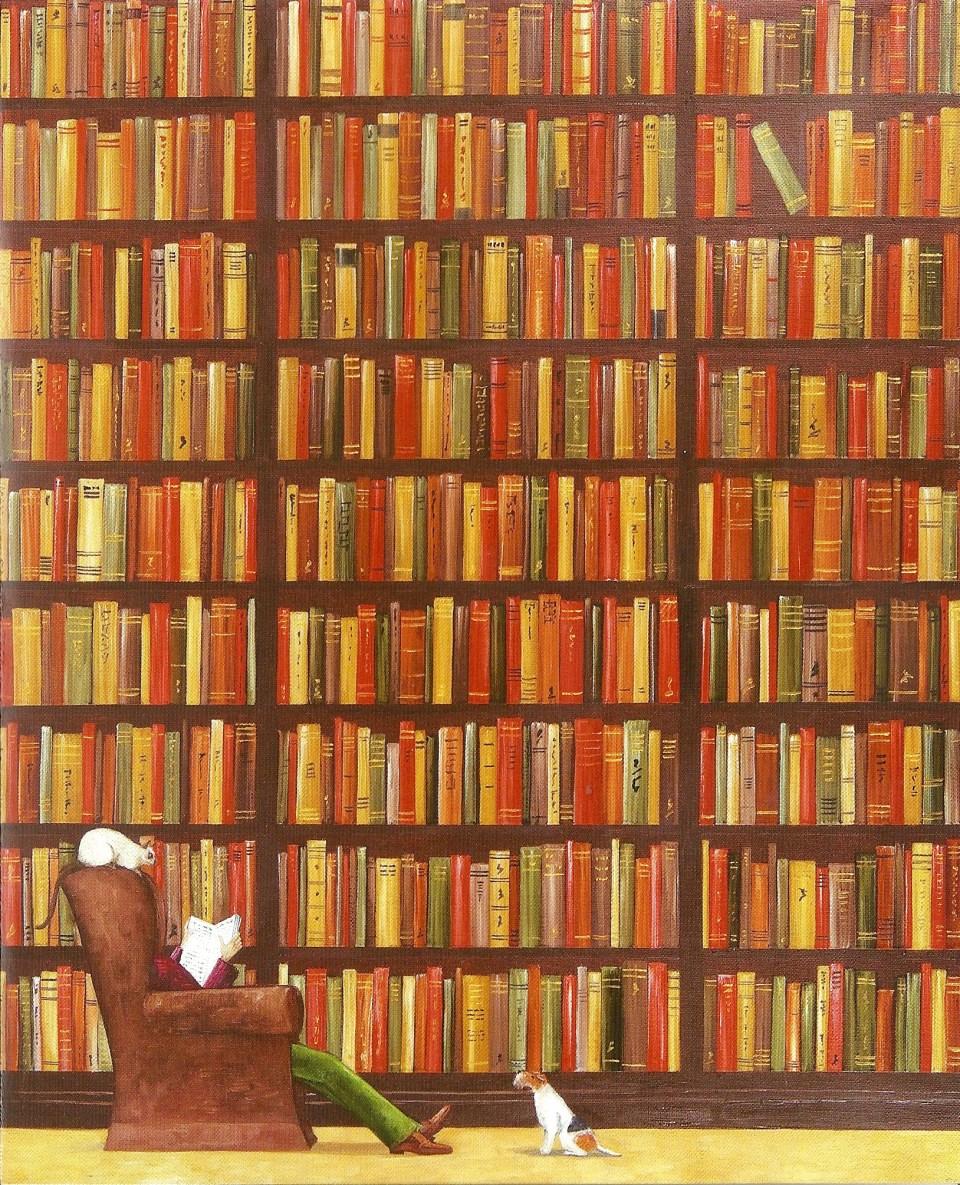

The birthday card I received from Mrs Blanco this year shows a partly hidden figure reclining in an armchair, cats in attendance, dwarfed by an enormous bookcase that, it is suggested, continues into the vastness of infinity.

She tells me this is how she sees me, which is interesting, and although I would not mind turning into the gentleman on the card at some point in the future, I still have a vague notion of myself as a passionate man of action, albeit with literary leanings. The fact that I have never, in actual fact, ever been a passionate man of action seems to make no impression on the part of me that decides on who I think I am. Like most people, who I think I am does not necessarily coincide with the way others see me.

Pursuing the theme of who we think we might become I have for some years now nurtured an image for my retirement – should such an event ever arise – that I once encountered in a poem (see below) by Jaime Gil de Biedma. I quoted this to a friend, the Scottish poet Tom Pow, a few months ago. He burst out laughing, and told me “But you’ve already lived like a derelict nobleman among the ruins of your intelligence. You did that in your twenties. You might be thinking of doing something differently in your retirement.” He is probably right. Nevertheless, I still like Gil’s poem, caught somewhere between irreparable nostalgia and a melancholy pleasure in the present, as reflecting an ideal way to finish one’s days on earth.

DE VITA BEATA

In an old and inefficient country,

something like Spain between two civil

wars, in a village next to the sea,

to have a house and a little land

and no memories at all. Not to read,

nor suffer; not to write, nor pay bills,

and to live like a derelict nobleman

among the ruins of my intelligence.

From Jaime Gil de Biedma, Las Personas del Verbo (1982) tr. R. Gwyn

Life in a Day

This is, in its way, a very contemporary film: a kind of visual equivalent of flash fiction. Based on thousands of hours of video recordings from a single day – 24th August 2010 – the editors have created a 90 minute collage of moments, some more extensive than others. Certain of the characters are seen once only, others are revisited several times over the course of the film, among which are a Korean man who has been cycling around the world for seven years (he has been knocked off his bike six times and had surgery five times: some drivers are very careless, he remarks, generously) and a trio of goatherds from somewhere in eastern Europe, who swear at their goats and are troubled by the prospect of wives and of wolves.

It could have been called ‘youtube: the movie’ but the point about all the mini-narratives being set within the frame of a single day gave it more coherence than might otherwise be expected. We do retain a sense of global village life with the weird juxtaposition of footage from a New York coffee shop being followed by African women preparing cassava while singing and a South American shoeshine boy stuffing his pockets with sweets. I left the cinema with the sensation that for so many people, desperately attempting to assert their own experience and their own lives, social networks and new media such as Facebook and youtube might provide a constant if imperfect means to an end. We all do it, especially if we blog, twitter and facebook (is that a verb?). Everyone can be Montaigne in the digital age. In a way, too, the film reflects the fetishization of travel familiar to us from ‘gap year’ philosophy, whether of the youtube variety, or the more polished, but equally nauseating version proposed to its readers every Saturday in the Guardian travel section.

A recent article by Christopher Tyler in The London Review of Books mentions how Colin Thubron, in his Shadow of the Silk Road imagines ‘conversations with a sceptical trader resurrected from antiquity. “I’m afraid of nothing happening,” he tells him, “of experiencing nothing. That is what the modern traveller fears . . . Emptiness.” In the current era, the notion of pseudo-travel has become available to all of us, emerging nervously from our terror of nothing happening.

Back home, I eventually retire to bed, to read. I have been reading poetry at night for a few months, but I also read fiction, and am currently with Claire Keegan’s Walk the Blue Fields, stories of profound clarity, steeped in the Irish storytelling tradition. While reading, I drift in and out of sleep. I wake at three in the morning with the book still in my hands, sitting up in bed and wavering in the space between sleep and non-sleep, though not yet wakefulness. This has become familiar territory. I have spent a long time being sleep-deprived, and am acquainted with this place, the zone. Drifting between sleep and not-sleep I am confronted by a person, standing at the foot of my bed. I am accustomed to this kind of intervention. Some call them hallucinations, but I know better.

This time he wears a cowboy hat. I ask him who he is.

“Calvin Bucket,” he says.

A likely story.

“Andy Coulson?” He suggests.

That’s better. I like the way these episodes meld with the fantasy that we call reality.

“Now, here’s how it is, Calvin, Andy, Cyrano, whatever.” I say. “You want to validate your existence? Fuck off and do it somewhere else, with someone who believes in you.”

And pouf. He vanishes.

The only ones validating their existence around here are me and my dog.

Dog on a Blog

What is this? A picture of a dog? But hey, it’s Blanco’s birthday, as well as mine – we share so many things; underwear, shirts, an inability to remember names – and you can do what you want on your birthday.

I never really intended getting a dog. Indeed have always felt quite hostile to the urban dog, and its owners. And as for those groups of dog owners who congregate eagerly in the park discussing the various merits of their canine companions, I give them a wide berth. But like other humans, I have a deep, cave-dwelling canine affinity and in my drinking days was known to befriend and hug many a stray and confide inebriated nothings into their doggy ears, when everyone else had long since stopped listening to me. The dog doesn’t mind, he thinks you’re just being friendly, even if you smell of mustard gas he doesn’t mind, because he probably does as well.

A German Shepherd once saved my life, when I slipped in the snow and started rolling down an Alp. Honestly. It was in Haute Savoie. He bounded down the hill through the snow and lay cross-ways in my path to stop me from rolling over a precipice. He had followed me from my friends’ remote home on a winter’s evening when, already well-oiled, I just had to walk five kilometres to the nearest bar. So on arriving in the village I took him to the Bistro instead and ordered him a raw steak. A group of local firemen eating their dinner were well impressed. That dog was called Flambard.

So, when I was ill, five years ago, and vegetating at home, unable to concentrate for long periods of time, and therefore read or write, because of a nasty condition called encephalopathy, I decided that a dog would be a good thing, and would force me to get more exercise. So I found a puppy, long since grown into a 25 kilo mad rollicking slavering beast, quite incapable of rational thought for even a moment, desperately affectionate, extremely fond of rolling in horse shit and insanely OCD where balls and sticks are concerned. Bruno Blanco, now approaching fifth birthday, pictured above in characteristic pose, quite mental, full-on, full-speed, even features in a literary work, albeit briefly. Still has a set of bollocks, even though Mrs Blanco has more than once suggested he might be better off bereft of them. I am fond of long walks in the hills, and for that reason alone a dog is a good thing. I wonder if I might cite a poem by Jane Kenyon? Let’s see. Thanks to John Freeman for passing it on.

After an Illness, Walking the Dog

Wet things smell stronger,

and I suppose his main regret is that

he can sniff just one at a time.

In a frenzy of delight

he runs way up the sandy road-

scored by freshets after five days

of rain. Every pebble gleams, every leaf.

When I whistle he halts abruptly

and steps in a circle,

swings his extravagant tail.

Then he rolls and rubs his muzzle

in a particular place, while the drizzle

falls without cease, and Queen Anne’s Lace

and goldenrod bend low.

The top of the logging road stands open

and bright. Another day, before

hunting starts, we’ll see how far it goes,

leaving word first at home.

The footing is ambiguous.

Soaked and muddy, the dog drops,

panting, and looks up with what amounts

to a grin. It’s so good to be uphill with him,

nicely winded, and looking down on the pond.

A sound commences in my left ear

like the sound of the sea in a shell;

a downward vertiginous drag comes with it.

Time to head home. I wait

until we’re nearly out to the main road

to put him back on the leash, and he

– the designated optimist –

imagines to the end that he is free.

Jane Kenyon

Otherwise: new and selected poems (Graywolf, 1996)