Midday: story of a kidnapping

Bogotá is the kind of place designed to make you feel conspicuous if you are toting a camera around. I have heard and read too many bad things, even if the place is considerably safer than it has been for many years. So I pootle down the main drag with my Argentinian bodyguard, drop into the national museum and see a few relics of pre-Columbian society (the Muisca, who lived in this region before the Spanish conquest, had a great love of gold, thereby giving rise not only the emergence of the myth of El Dorado, but also to their own extermination). In my conversations with Colombian writers and taxi drivers, I encounter a state of general uncertainty, of not knowing what exactly constitutes the New Colombia, or which way the wind will blow. With respect to the taxi drivers, this uncertainty seems to extend to their knowledge of the city, because they never seem to know their way around, and are obliged to ask directions of their customers, or else stop and ask one of the many patrolling police and military. This, in fact, is the most noticeable feature of the city at night: the fantastic quantity of military and police personnel on the streets. Like living in a city under occupation. But for many Colombians this actually comes as a relief, after so many years of lawlessness. Colombia has lost its pole position as the murder, kidnap and extortion capital of the world, but like other south and central American states lives with its legacy of such crimes, carried out on a massive scale. The balance of terror in this part of the world seems to be shifting elsewhere: Mexico we know about already, and yesterday I listened to a long account of the emergence of horrific acts being carried out by juvenile crime gangs in El Salvador.

All this brings me in a roundabout way to the story of a kidnap, or abduction. The latter term in generally used to describe a politically motivated sequestration, while a kidnapping suggests a demand for ransom. But in English ‘kidnap’ still retains the general flavour of being taken against one’s will whether for political reasons or for financial gain. So we’ll stick with kidnap.

I reproduce the story that follows with the kind permission of its Guatemalan author, Eduardo Halfon. It is taken from the collection Elocuencias de un tartamudo published in Spain by Pre-Textos in 2012.

MIDDAY

We were lying beneath the branches of a fig tree, watching a group of sailing boats as they crossed the shining, almost breezeless lake, when he told me that the only time that he had wanted to do drugs was after his kidnapping.

– Mushrooms, in particular.

He slapped himself on the neck, inspecting his fingers to see if he had got the mosquito.

– I couldn’t remember the details of the kidnapping. Imagine that! And I reckoned that maybe a psychotropic drug like mushrooms might help me to remember something.

Voices and laughter drifted towards us from the house and from the Jacuzzi, which was fed by volcanic waters.

– I could remember, for example, that they had taken me one morning as I was arriving at my clinic. I could remember that a woman helped me out at night, loosening the ropes and shackles so that I was able to sleep better. But not much more.

He was lying in a deckchair, dressed only in his navy blue Speedo. His skin glistened with oil.

– Then I went to see a psychoanalyst in Alabama, and I told him I wanted him to prescribe me some drug, in order to remember.

A swallow skimmed the pea soup coloured water. It seemed to be hunting something.

– And the psychoanalyst told me no, that he wouldn’t do that, but was I willing to allow him to hypnotize me.

A cheerful shout from someone in the Jacuzzi interrupted him.

– Once I was hypnotized the first thing I remembered was waking up naked on the floor of a darkened room, and not recognising myself. Do you understand? I didn’t recognise myself. An atrocious thing. Everything was so alien to me I had even lost all notion of my self.

A motor launch was pulling a lone water-skier.

– I didn’t know who I was.

He paused, as though wanting to remember something else. On the other side of the lake, between misty green mountains: a burning purple jacaranda.

– And then I recognized my Kickers.

He had said this in a relaxed tone, almost a sweet tone, and I laid off looking at his bare feet, his tanned and grey-haired chest, his opaque gaze, his immaculate, old hands trying to shoo away another mosquito.

– I didn’t know anything. I didn’t even know who I was. But all of a sudden I recognised my Kickers in a corner and then I recognised myself as well, on account of or thanks to my Kickers.

We heard the splashing of wet people as they left the jaccuzzi.

– But look, it’s midday already – he said, checking the time on his digital watch –, and the bar opens at midday.

I watched him get up calmly. At four foot nine, he seemed like a giant.

– Martini?

© original text: Eduardo Halfon 2012 © translation: Richard Gwyn 2013

A story always tells two stories

‘A story always tells two stories . . . the visible narrative always hides a secret tale’. Attempting an overhaul of my laptop’s photo collection, I come across a picture of Eduardo Halfon, standing across the road from Coffee a Gogo in Cardiff, in front of a makeshift sign that (miraculously) cites the opening lines of his book, The Polish Boxer. No one is sure how the signs got there, but we have our suspicions. Tellingly, the word ‘tells’ is missing. It reappeared by the evening of that day. I wonder where it went in the meantime, and what it told.

Meanwhile, from Bogotá, a photo from my hotel bedroom on the 13th floor, overlooking Avenida Septima. This distorted image – taken through a rather dirty window framed by outside bars – captured for me the fuzziness of arrival, and waking to a morning in the capital of a country whose catastrophic history tells so many secret tales that the visible narrative has almost disappeared entirely.

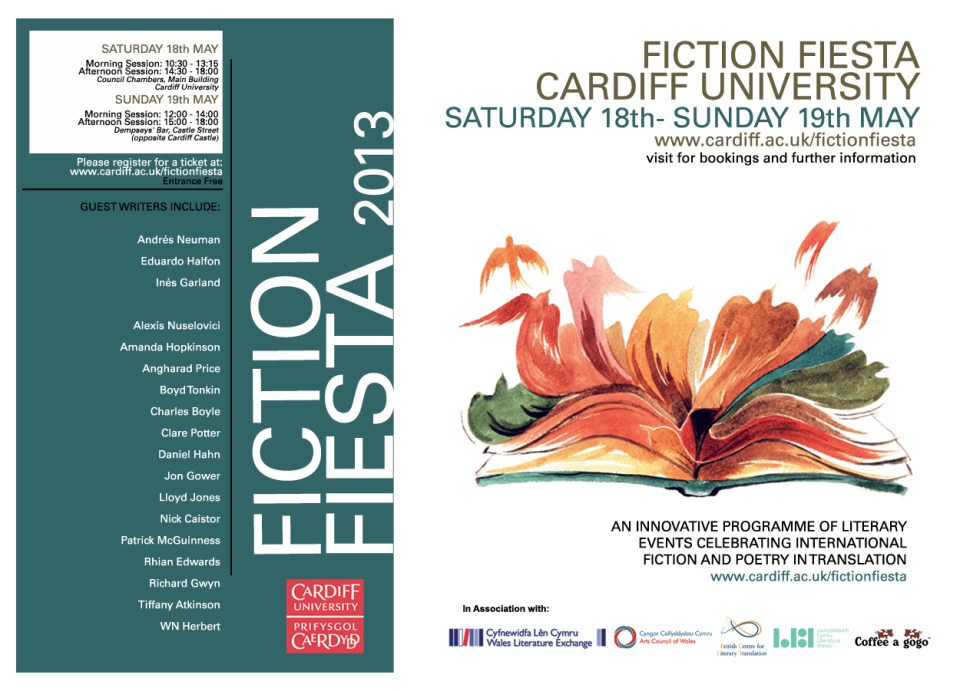

Fiction Fiesta 2013

The poster for the second Fiction Fiesta is ready.

Fiction Fiesta is an intimate but international festival, specializing in fiction and poetry in translation. The plan is to team novelists and poets from Latin America with writers from Wales and the rest of Great Britain and Ireland: the writers will read and discuss their work and answer questions from the public.

Fiction Fiesta will provide a forum for all people with an interest in international literature, from professional translators to the merely curious. Fiction Fiesta is a festival with a difference, involving readings and discussion that will bring the public into contact with some of the best writers from around the world, in a friendly and informal setting. The event is free, but each year we will be inviting guests to donate to our chosen charity: this year we will be supporting the work of Education for the Children in Guatemala.

The 2013 festival takes place over two locations: the Council Chamber in Cardiff University’s Main Building on Saturday 18th and Dempseys’ Bar, opposite Cardiff Castle on Sunday 19th May. Our guest writers and translators are listed in the poster above (squint or zoom) and include our Latin American guest Andrés Neuman (author of Traveller of the Century – shortlisted for The Independent foreign fiction prize this year), Eduardo Halfon (author of The Polish Boxer) and Inés Garland (author of Una Reina Perfecta). Both Andrés and Inés are featured in the forthcoming 100th issue of New Welsh Review, while Eduardo’s Polish Boxer is my favourite new fiction collection of the past twelve months.

You can find out more on the Fiction Fiesta Facebook page.

More to follow.

The cities within yourself

This has been Turkish week, but also – and with a synchronicity that pleases me very much – Greek week. The London Book Fair had Turkey as its ‘Market Focus’ and two expeditionary groups of Turkish writers descended on the city of Cardiff (whose football team, it will be noted, are playing in the Premier League next season). Meanwhile, I have been immersed in the work of the Greek poet, C.P Cavafy, whose 150th anniversary we celebrate this year.

The first group of visitors were poets, three of whom I have been involved in translating. They are Gökçenur Ç, Efe Duyan, Adnan Özer and Gonca Özmen (the illustration above shows the cover of a booklet of their work, produced by Literature Across Frontiers, The Scottish Poetry Library and Delta Publishing). After an unforgettable lunch (which deserves a post of its own), the poets were joined by fellow-translator Zoë Skoulding and Literature Across Frontiers director Alexandra Büchler for an evening of poetry and conversation at Coffee a Gogo, just across from the national museum of Wales.

Then on Thursday, we were visited by the Turkish novelists Ayfer Tunç and Hakan Günday for a reading and discussion of their work, under the heading ‘Alone in a crowd’. The idea was to discuss the theme of cities – our citizenship, I guess – or experience as city dwellers. When preparing for my own contribution, I was immediately reminded of a line by one of the Turkish poets I hosted last weekend:

The more you travel the more cities you will find inside yourself

Which had led me to ask its author, Adnan Özer, how well he knew the work of Cavafy, a writer of whom I have been a fan, no, a devotee, since my mid-teens. Adnan told me that he admired Cavafy’s work, but that he was not a major influence, apart from in that particular poem.

The poem behind the poem, if you like, is this one:

THE CITY

You said: “I’ll go to another country, go to another shore,

find another city better than this one.

Whatever I try to do is fated to turn out wrong

and my heart lies buried as though it were something dead.

How long can I let my mind moulder in this place?

Wherever I turn, wherever I happen to look,

I see the black ruins of my life, here,

where I’ve spent so many years, wasted them, destroyed them totally.”

You won’t find a new country, won’t find another shore.

This city will always pursue you. You will walk

the same streets, grow old in the same neighborhoods,

will turn gray in these same houses.

You will always end up in this city. Don’t hope for things elsewhere:

there is no ship for you, there is no road.

As you’ve wasted your life here, in this small corner,

you’ve destroyed it everywhere else in the world.

(translated by Edmund Keeley and Philip Sherrard)

And it seems here, as in Adnan’s paraphrase, that the city is a cypher for the self, reflecting our fragmented or multiple selves. We know that Cavafy is speaking of his own beloved Alexandria, but we also know that the city here is a state of mind, one’s personal predicament – and the human predicament also – from which one can never shake free.

At the same time as being surrounded by a crowd, we are all ultimately alone (in the city, as elsewhere), despite the onslaught of synthetic familiarisation on offer from substitute communities such as Facebook and Twitter. On which theme, I was interested to read, in Russell Brand’s Guardian piece that he singles out one La Thatcher’s most devastating legacies in precisely this area. In the quest for personal advancement at all costs, in the elevation of blind greed as the most praiseworthy and rewarding of human qualities, we are almost duty bound to ignore the needs of those we share the world with. As her loathsome sidekick Norman Tebbit said, in reference to the defeat of the mineworkers’ union:“We didn’t just break the strike, we broke the spell.” The spell he was referring to (writes Brand) is the unseen bond that connects us all and prevents us from being subjugated by tyranny. The spell of community.

And if that all seems a bit random, Turkish week at LBF>Cardiff City Football Club>Turkish poets>Famous Greek Poet>living in the city>Thatcherism and its legacy – then please forgive me. It does connect, I promise. And if it doesn’t, well, like I said once before . . . blogging is a way of thinking out loud.

On Not Getting It

Curiosity can sometimes be more satisfying, more enhancing, than the mere consolation of achievement.

A while ago I wrote here on Kafka’s claim that in spite of knowing how to swim, he had not forgotten what it feels like to not know how to swim – and consequently the achievement, or consolation of ‘being able to swim’ was only of any value when weighed against the state of curiosity and mystery of not knowing how to swim.

Or something like that.

Adam Phillips, in his excellent book Missing Out, says something very close to this. In the chapter ‘On Not Getting It’ he writes that sometimes ‘not getting it’ (whatever ‘it’ might be – knowing how to swim, or winning some straightforward or else obscure object of desire) is more interesting than ‘getting it’. He imagines a life ‘in which not getting it is the point and not the problem; in which the project is to learn how not to ride the bicycle, how not to understand the poem. Or to put it the other way round, this would be a life in which getting it – the will to get it, the ambition to get it – was the problem; in which wanting to be an accomplice didn’t take precedence over making up one’s mind.’

There is something very appealing about this notion of ‘not getting it.’ Here’s more:

‘What I want to promote here is the alternative or complementary consideration; that getting it, as a project or a supposed achievement, can itself sometimes be an avoidance; an avoidance, say, of our solitariness or our singularity or our unhostile interest and uninterest in other people. From this point of view, we are, in Wittgenstein’s bewitching term, ‘bewitched’ by getting it; and that means by a picture of ourselves as conspirators or accomplices or know-alls.’

For now, I am surprisingly happy to be bewitched by the notion of not getting it; to remain enhanced if occasionally bewildered by my inability or disinclination to get it.

Poets who translate

It is our last day in Istanbul, and the rain continues, as it has done since Friday evening, shrouding the Bosphorous in grey mist. Before catching a taxi to the airport we snatch a visit to Aghia Sophia, that magnificent evocation of the implausible. The days of translation, of this particular kind of translation, have drawn to an end. Yesterday evening WN (‘Bill’) Herbert, Zoë Skoulding and a certain Richard Gywn, along with our respective translators, Gökçenur Ç, Gonca Özmen and Efe Duyan read our work at the Nazim Hikmet Centre in Kadikö on the Asian side. We went by ferry through the soft rain, a rain almost as comforting as the sahlep we slurped, that peculiar sweet beverage of orchid root, milk and cinnamon, the liquid polyfilla of the Levant, as Bill calls it.

We had an early dinner at Çiya, one of Istanbul’s most successful new restaurants, whose owners have set out to collect recipes from lost corners of Turkey and recreate them in a modest but harmonious three-storey building. I should really say they have translated recipes found on research trips, dug up from family notebooks, dictated by aunts and grandmothers, and have brought them to an Istanbul all too well known for its predictable variations on ratatouille and lamb combinations as a reminder of the glorious culinary past of Anatolia. These recipes have been translated from a time and place distinct from our own, rejecting the universalist culture in which the staple has become ever more dull and tasteless.

It is easy to forget that translation is something we are engaged in, without option and at all times, from the very start of life. It is an activity that is by no means confined to those who term themselves ‘translators’.

Early childhood is the acute phase of translation, and of being translated. Those moments in which every gaze, every enraged instinct on the part of the infant meets with either incomprehension or else with a tentative, and then a more assured translation. Maybe we don’t change that much in this respect, as we continue to translate others, and ourselves, in and throughout the course of a lifetime, with varying degrees of success. The fact that we exist as part of a functioning element within society (family, school, member of this or that group or organisation) consigns us necessarily to different modes of translation.

Literary translation concretizes and makes specific acts of translation that otherwise exist in our everyday lives. Poets who also translate join a community of international poet-translators who are enabled, through a process of collaboration, to sharing their respective poetry with new audiences. Many lasting friendships are made in the process, as well as dialogues being opened between cultures in essential and surprising ways.

This is what the organization Literature across Frontiers – under its indefatigable director Alexandra Büchler – manages to such good effect. In meetings across Europe practitioners use a ‘bridge’ language, so that poets who have different first languages but share another language in common (English, most commonly, but any language will do) can combine forces with a native speaker of the bridge language to make new versions of their work. It sounds complicated but it can be a very stimulating process, and it must be said that a lot depends on the individuals gathered together on these occasions, and whether or not they gel as a team. Working as a small unit has other benefits – there are always at least two perspectives – indeed, as many as four or five– on a single poem, and this multiplexity of approach can lead to small epiphanies in the act of translation. Translation is not only a linear and logical progression of a text from one language to another; it is also a process of revelation, an uncovering, de-layering: a transmutation of materials, an act of linguistic alchemy.

Sometimes, needless to say, translation goes all wrong. I have written about this before, in relation to restaurant menus, a constant source of entertainment for anyone who travels. But in the last few days, Istanbul has coughed a few examples of translation weirdness that are equally diverting. I post a selection below.

The other side of the other

In my last post I mentioned that perennial companion and source of consternation, the other, the doppelganger, the one who walks beside us, both ourselves and not ourselves.

I cited the introduction from Orhan Pamuk’s memoir of Istanbul, but cut the quotation short. I did this on purpose, because Pamuk leads off into the dark side of the other, to the fear of replication that beset him when he once came to grips with the awfulness of one’s own doubling:

On winter evenings, walking through the streets of the city, I would gaze into other people’s houses through the pale orange light of home and dream of happy, peaceful families living comfortable lives. Then I would shudder, thinking that the other Orhan might be living in one of these houses. As I grew older, the ghost became a fantasy and the fantasy a recurrent nightmare. In some dreams I would greet this Orhan – always in another house – with shrieks of horror; in others the two of us would stare each other down in eerie, merciless silence.

‘As I grew older’. There’s the rub. Just as all literature leads us back to children’s stories, as Borges notes, so, in an inverse sense, stories that begin as childhood diversions, of daydreaming and harmless fantasy, with time become the stuff of nightmares. The prospect of possessing (or being in the possession of, possessed by) a double, a version of oneself both intimate and foreign, both known and unknowable, intrudes into consciousness with the stealth of a thief, come to steal our bones, come to steal our soul.

After reading my last post, The one who walks alongside us, a friend commented that in Freud’s essay ‘The Uncanny’, he refers to the terror implicit in the concept of the double, the creeping horror of replicating something long known to us, once very familiar, but which has now become terrifying. What could be more familiar to us – and therefore possess the greatest potential for horror – than ourselves?

In literature, notably in the works of Edgar Allen Poe, Guy de Maupassant, Alfred de Musset, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Joseph Conrad, Jorge Luis Borges and Thomas Bernhard, we frequently encounter something approaching a paranoid state revolving around the persecution of the ego by its double. Otto Rank, Freud’s precursor in the study of the double, compares these imaginary creations to their authors’ symptoms, through which the theme of the double reveals a psychopathological dimension. Well . . . you might see it that way, you might even, as Freud suggests, see the expression of the double as a symptom of the ego’s inability to outgrow the narcissistic phase of early childhood, but that would be to pathologize a great number of writers, and I don’t for one moment believe in the notion that you have to be mentally ill to be intrigued by the notion of a double, or to write effectively on this theme, or to be encouraged to think there may be some profound connection between an awareness of one’s own otherness (expressed in many ‘traditional’ cultures as an animistic belief in immortality) – or to believe that after a certain age it should be regarded as an unhealthy or pathological condition.

We all possess the ability to imagine ourselves as other, and this imagining, or daydreaming, is the beginning of all literature. How appropriate then, that when a writer sets out to put down an account of his or her own life, they seem best able to do this by imaging their story as one that happened to someone else. It seems to be the core paradox that confronts anyone who writes a memoir, and has certainly been my own experience.

Pamuk too, apparently: “I’d have liked to write my entire story this way – as if my life were something that happened to someone else, as if it were a dream in which I felt my voice fading and my will succumbing to enchantment.”

More to follow. Written either by me, or the other bloke.

The other who walks alongside us

On the radio this morning the Turkish writer Elif Shafak prepares me for a journey. I am listening to Istanbul, she says, and we share the sounds of the city, which dissolve, eventually into water. ‘Everything in Istanbul,’ she says, ‘is fluid.’ And there are two different kinds of fluidity, the elements of oil and water. It is a liquid city, a city that never stops becoming.

Istanbul’s fluidity, its sense of becoming, of becoming another, even at the same time as becoming itself, reminds me of the opening of another work by a contemporary Turkish writer. Orhan Pamuk begins his love poem to his home city: Istanbul: Memories and the City, as follows:

From a very young age, I suspected there was more to my world than I could see: somewhere in the streets of Istanbul, in a house resembling ours, there lived another Orhan so much like me that he could pass for my twin, even my double. I can’t remember where I got this idea or how it came to me. It must have emerged from a web of rumours, misunderstandings, illusions and fears . . . But the ghost of the other Orhan in another house somewhere in Istanbul never left me.

How many of us must share this notion of a double, breathing our air, thinking our thoughts, eating our food, dreaming our dreams; but also at a remove, always elsewhere, always and inevitably engaged in being someone other than ourselves.

The itch

Wikipedia’s entry on itching goes as follows:

Itch is a sensation that causes the desire or reflex to scratch. Itch has resisted many attempts to classify it as any one type of sensory experience. Modern science has shown that itch has many similarities to pain, and while both are unpleasant sensory experiences, their behavioral response patterns are different. Pain creates a withdrawal reflex while itch leads to a scratch reflex.

My own scratch reflex has been horribly over-employed these last two nights. I wonder if it has anything to do with a change of climate, being currently in a temperate dry place rather than the cold wet place where I normally reside? I came here to do some work, and while I have managed to do a fair bit of writing, I have probably done just as much scratching, often in the more personal or inaccessible zones of the body. I haven’t scratched like this since having scabies a long time ago.

The doctor back home told me it might be a side-effect of the medication I am on (great, I thought, another side effect to go with the fatigue, loss of appetite, anaemia, depression and rage). He also told me – get this – to try not to scratch.

Well, as you can imagine, I laughed like a cretin, since the very essence of having an itch is – as the Wikipedia entry makes clear – to activate the scratch reflex. You think, I’ll just give it a little scratch, and the next thing you are at it like a monkey. When you use your fingernail to scratch the spot where the irritant is, you not only remove the irritant but you irritate a whole shedload of other nerve endings. This means your itch itches more, hurts more, and you consequently scratch more. So my doctor’s advice was actually very helpful, if only I was able to heed it.

All I could do last night was take a valium and keep my hands clenched together under the pillow, in an attempt to exercise the kind of self-control that would do credit to a monk dedicated to obliterating the demands of the flesh.

There is, I suspect, a literary aspect to this scratching business. In fact the whole thing reeks of metaphor, if only because writing itself at times resembles an act of scratching. Initially one writes in order to relieve an itch. However once the process has begun, the initial itch is replaced by something quite monstrous. Then we find it impossible to stop scratching. I wonder if this has anything to do with being on the seventeenth draft of a novel?