Notes on (mis)translation (1)

It has been said that the most interesting aspect of translation is mistranslation — or, to put it another way, translation only gets noticed when it goes wrong. Everyone has their mistranslation stories, and there are now new ways in which AI-assisted translations can generate a laugh.

I thought I would collect a few favourites, and do a little series. Since I am currently in Spain, I’ll offer a couple from last week’s trip across the north of that country.

The first comes from a packet of potato crisps (called ‘chips’, with a long ‘ee’ sound in Spanish).

The packet informs us in Spanish that they were ‘fritas en sarten’ — which suggests that the crisps (or chips) were fried in a pan (‘sartén’ is a frying pan or skillet). This is unlikely to be true, since hand-cooking millions of potato slices in an individual frying pan could not be a cost-effective way of producing hundreds of thousands of packets of crisps. Surely they would have been cooked in a single, industrial-sized container?

But the translation is ‘chips in frying pan’ which suggests not so much that the things were cooked in a particular way, but that they are to be purchased along with the item in which they were allegedly fried. Confusing.

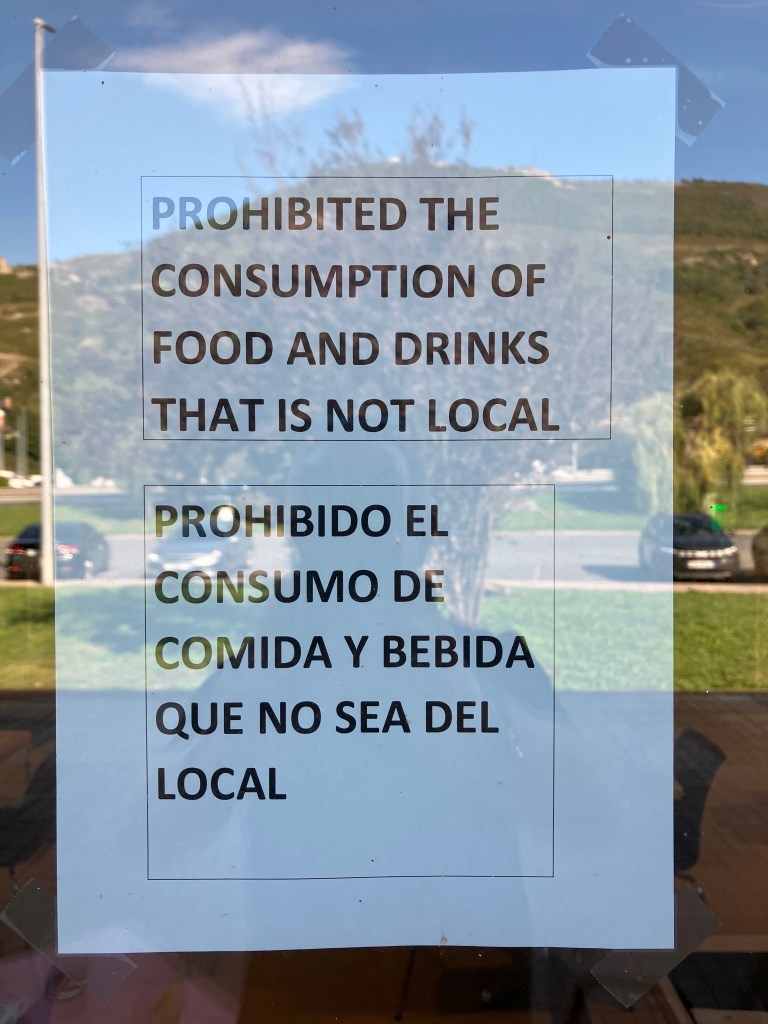

The second of today’s examples of mistranslation was taped to the window of a service station diner on the motorway between Bilbao and San Sebastian. ‘Local’ in this context might be translated as ‘the premises’, i.e. the shop or restaurant outside of which Mrs Blanco and I were seated. It might have read read, ‘Food not purchased from these premises should not be consumed here’ or some such, but certainly not the following, which suggests the promotion of locally-produced foodstuffs:

Gaudí’s Folly

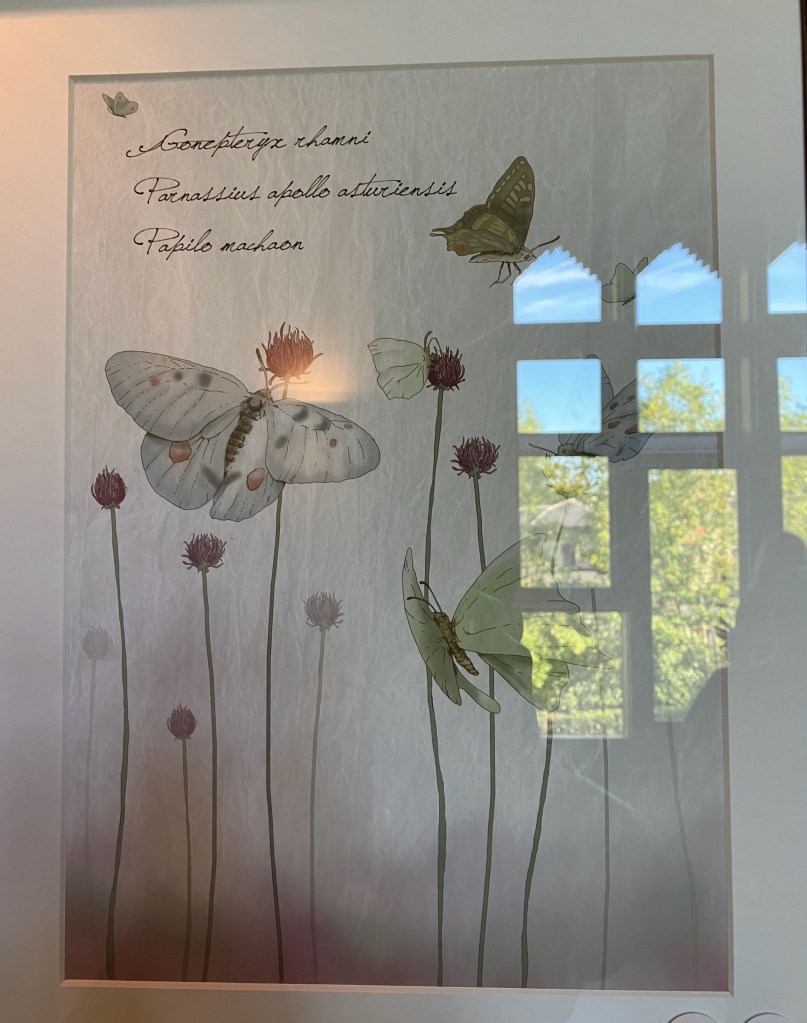

Comillas, on the Cantabrian coast, was for centuries a small fishing port of no great importance — whaling was the main industry — until in the mid nineteenth century, Antonio López y López, born into an upper class family fallen on hard times, decided to reverse the family fortunes and become a millionaire. Like so many before him, he set off to the Americas — in his case to Cuba — and returned a very rich man, while still relatively young. He made important friends, among them the king of Spain, Alfonso XII, who bestowed on him the title of Marquis of Comillas, and he built a palace on the hill in his home town. Because of his many shady dealings, he wanted his trusted lawyer near to hand, so on a vacant plot near to his palace, he installed Máximo Díaz de Quijano; and the young Antoni Gaudí — whom the Marquis had met through his Catalan connections (he was married to a Catalan) was commissioned to design the house. Máximo’s passions were nature and music, and these twin themes formed the basis for Gaudí’s architectural plan. As such, the house contains fastidious detail with regard to these two interests, including musical weights attached to the sash windows and representations of flora and fauna throughout the building — from sunflower tiles to butterflies and birds on the stained glass. Unfortunately the house was never completed. Máximo died a week after moving in, from cirrhosis — contracted, no doubt, by a love of rum acquired over long tropical nights in Cuba.

We visited the house, known as El Capricho de Gaudí — or Gaudí’s Folly — on a sunny afternoon, and were shown around by our excellent guide, Andrea, whose explanations of the social and political background, as well as the exquisite detail of Gaudí’s design, were filled with insight and humour.

The next morning we set off into Asturias, along a winding mountain road. In search of a picnic spot midway, we happened upon a medieval bridge called Puente La Vidre, which spans the diaphanous waters of the Río Cares. There was no one around and I took an icy swim. Next stop: the Picos de Europa and Covadonga.

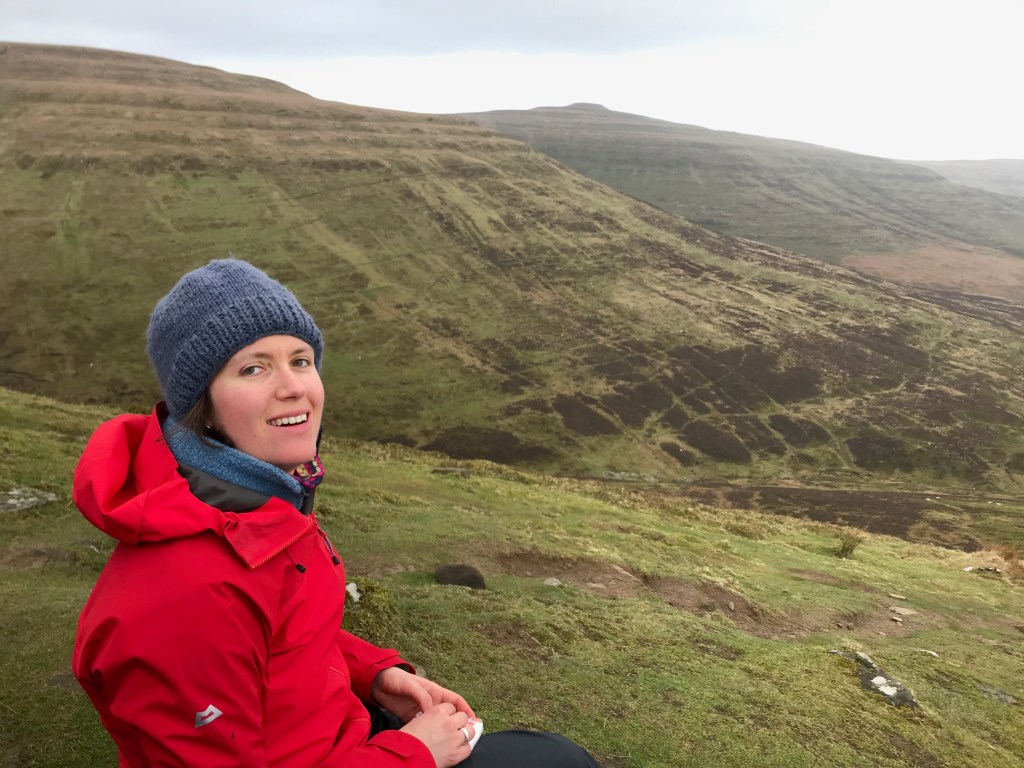

The hill of wild horses and the nature of risk

Sometimes things fall into place in a way that suggests an omniscient narrator is writing the script, and you are merely a pawn in the plot. On a hill named Pen Gwyllt Meirch — the hill of wild horses (or stallions) — you stop beside a string of them as they graze, just as this pair — who have been nuzzling at each other’s necks as you approach, embark on a silent dance, with only the wind as accompaniment. After their exuberant pas de deux, they return to the group, as the others look on.

You have to find a way toward the ridge, but the path has petered out, and the ridge is an ever-receding goal. This is common enough, in life as well as hill-walking. Here, the soft contours are deceptive, and each rise conceals the next, offering a continuous retreat from view, a problem you give little thought to nowadays.

As a child, walking in these hills, you often felt as though the longed-for ridge would never arrive, and you would nurture a deepening sense that however many times the hillside flattened out to reveal yet another ascent — even as you scurried over gorse and heather — there would always be another rise ahead, and you would never reach the top.

You might say this was an elementary lesson in philosophy. False horizons are always going to mislead you; there will always be another peak and another plateau, just as, in any kind of excavation —downwards, into the heart of the matter, whatever the matter might be — another layer always seems to accrue in the process of discovery, even as you dig. The problems of descent are no less fraught than those of ascent.

But on this mid-May day of uninterrupted sunshine, after months of overcast and wet weather — which nonetheless leaves our reservoirs depleted, because the spring downpours have not compensated for the lack of rain over the past twelve months — there is a spring to your step. You are climbing towards the ridge, and those horses have you thinking of something the French philosopher Anne Dufourmantelle wrote, in her essay, Power of Gentleness: Meditations on the Risk of Living.

‘What the animal disarms in advance, even in its cruelty (outside the range of human barbarity), is our duplicity. The human subject is divided, exilic. If the animal’s gentleness affects us this way, it is undoubtedly because it comes to us from a being that coincides with itself almost entirely.’

And what does it mean, to coincide with oneself almost entirely?

Anne Dufourmantelle might herself provide the answer. She dedicated much of her working life to an examination of risk, of the importance of taking risks, and the need to accept that exposure to any number of possible threats is a part of everyday life, from which we cannot be protected by the false and pernicious security manias of the powers that be. She wrote, regarding risk, that ‘being completely alive is a task, it’s not at all a given thing. It’s not just about being present to the world, it’s being present to yourself, reaching an intensity that is in itself a way of being reborn.’ Her best known work, In Praise of Risk, extols the virtues of risk-taking in words that leave little doubt as to her intention:

‘“To risk one’s life” is among the most beautiful expressions in our language. Does it necessarily mean to confront death — and to survive? Or rather, is there, in life itself, a secret mechanism, a music that is uniquely capable of displacing existence onto the front line we called desire.’

Dufourmantelle drowned in 2017 in the Mediterranean after attempting to save two children, unknown to her, at a beach on the French Riviera, but she did not survive. She swam after them when they got into difficulty in strong winds at Pampelonne beach, near St Tropez, but was herself carried away by the strong current. The children were later rescued by lifeguards and were unharmed, but attempts to resuscitate her were unsuccessful.

Of all the risks we might take, she believed that risking belief was perhaps the most crucial:

‘To risk believing is to surrender to the incredible . . . to surrender oneself not to reason but to the part of the night that lives in us . . . and obliges us to look towards the top.’

Looking towards the top and believing in the summit, even though it is invisible and receding, always on the retreat, is much like staring down into a fathomless pit in which the accretion of nothingness appears impenetrable: is this what you needed to learn as a child? And did you learn your lesson?

Returning to animism in the Anthropocene

Sometimes a book comes along that enhances your way of being in the world: for two such books to fall into your hands, in serendipitous collusion, is a thing to marvel at, and perhaps even to write about. Whatever their differences, and they are legion, the two books under review, both written by young women — one a memoir by an anthropologist, the other a piece of fiction that reads like a fable — together provide a thorough dismantling of the notion of genre. But more importantly, both books open a window onto systems of belief in which humans and other animals, plants, fungi and diverse organisms survive and thrive in interconnected and interdependent ways, consciously or otherwise, reflecting an unexpected harmony at the heart of lived experience.

The first story begins with its author lying wounded on a mountainside in a remote corner of eastern Siberia. It is here that the French anthropologist Nastassja Martin is living, among the Even people of Kamchatka, a community of nomadic hunters and erstwhile reindeer herders. She has just had a confrontation with a bear that has left her close to death. She hears the bear’s teeth closing, the sound of her jaw and skull cracking, feels the darkness inside the bear’s mouth, the moist heat of his breath. In a split-second decision that saves her life, she has the presence of mind to swing an ice axe through the bear’s leg, and he flees, stumbling away across the high steppe.

After eight hours of waiting out in the open, and with the help of a friend who raises the alarm, a Russian helicopter appears and takes Nastassja (or Nastinka/Nastya, as she is known to the locals) to the nearby village of Klyuchi. Here, an old woman begins stitching up her head, which by some miracle has not been entirely crushed. But just then, a ‘fat, sweaty man’ bursts into the room, and in a gesture that foreshadows much that Nastinka will have to endure in the months to follow, attempts to photograph her, so that her ruined face can be saved for posterity. She is enraged, and wants to hurl herself at the man, ‘tear his paunch open, rip out his guts, and nail his damn phone to his hand’. Fortunately for both of them, she is too weak to move. Taking matters in hand, the old woman pushes the man out of the room and locks the door. After a second helicopter ride, Nastinka emerges from unconsciousness to find herself stripped naked and strapped to a bed in a vast and decrepit room, a tube running from her nose to her throat, a tracheotomy stuck to her neck. She is in the intensive care unit of the military hospital at Petropavlovsk, a crumbling Soviet era building, where she undergoes the first of several operations. Here she is attended by a malevolent teenage nurse who injects mashed food through a tube into her stomach, wanting revenge, as Nastinka imagines, for everything that is wrong with her life. Nastinka feels as though she is at the very limits of human endurance, and despite pleading with her carer-captors, she remains strapped to the bed (‘to protect you from yourself,’ she is told). Meanwhile, the head doctor, dripping with gold jewellery, seduces the female nursing staff, nightly, one by one, in a room adjoining the ward; the moans of their lovemaking reverberate through the ward, empty apart from Nastinka. It feels as though she is in Bluebeard’s castle, and the story unfolds like a warped fairytale, or a David Lynch screenplay transplanted to deepest Siberia. When Nastinka demonstrates good behaviour and is eventually released from her bonds, she is rewarded by Bluebeard, who wheels in a small television, which is set up at the foot of her bed. As though steered by some perverse law of symmetry, a film is showing that tells the story of a young woman called Nastinka who is desperately searching for her lover in the forest: he has been transformed into a bear and Nastinka does not recognise him. Unable to make her see him for who he is, her lover dies of grief. This is all too much for the real Nastinka, who cannot help but compare this tale with her own, given the fact that among the Even community with whom she lives, she has already — before the attack — been given the name of matukha, or ‘she-bear’. It feels as if she has entered a world of mirrors, or else an endless spiral in which she is forever to be confronted by her ursine other. She bursts into tears and the television is taken away.

As Nastassja Martin, she is interrogated by a Russian FSB (secret services) agent, on the basis that she has spent most of her time in a militarised zone occupied only by Even hunters, who live in a state of almost complete self-sufficiency. She spends three hours with the agent, who is the first, but not the last person to intimate that to be an anthropologist is to be a spy. Her two families turn up; Nastassja’s birth family from France, and Nastinka’s adopted Even family from the forests of Kamchatka. The two groups of her loved ones look nothing like one another, speak different languages, and come from different worlds; the two worlds between which she is riven. One of the nurses looking after her tells her: ‘Nastya, you might almost say there are two different women occupying this room.’ An astute observation, but perhaps more accurately there are three of her, if you include the bear.

Arriving in Paris for further treatment, Nastassja finds herself at the centre of a Franco-Russian medical cold war. The surgeons at the Salpêtrière hospital want to take the ex-Soviet metal plate from her jaw and replace it with a shiny new French one. Meanwhile, she receives a visit from the hospital psychotherapist who asks her how she is feeling, ‘because, you know, the face is our identity.’ Nastassja looks at the therapist, aghast. She asks her if this is the kind of information she offers all the patients at the hospital’s maxillofacial clinic. She wants to tell the therapist that she has ‘spent years collecting accounts of the multiple presences that can co-exist within a single body, precisely in order to subvert this concept of singular, uniform, unidimensional identity,’ but in the end relents and replies simply: ‘I think it’s a bit more complicated.’ She replays the encounter with the bear every evening, before falling asleep, and she dreams terrible dreams, in which she meets bears that ‘loom tall, brown and menacing’. She is adrift between worlds again, between sleep and waking, between ‘here’ and ‘there’. While appreciating the narcotic release of sleep she wants to return to the Arctic night, to be without sun or electricity. She wants to stare into the darkness, to go underground, to speak to her bear.

During her long recovery from ‘the bear’s kiss’, as she fondly calls it, she interrogates the events that will lead her towards an understanding of what has happened to her; and to this end unspools an attentive and passionate account of the people and animals amongst whom she has lived. Ultimately, too, she shares her confusion, her inability to decipher the timeless puzzle with which she is confronted. She finds herself at the very limits of interpretation.

Central to the cosmology of Siberian hunting peoples such as the Even, and to hunter-gatherers in general, is a belief in the interconnectedness of relations between humans, animals and the landscape they share. (It should be pointed out that Martin’s book was titled Croire aux fauves — ‘To believe in wild beasts’ — in the original French, which gives a far better idea of what it is about than the rather anodyne or ambivalent In the Eye of the Wild.) Martin studied under the French anthropologist Philippe Descola, and her chosen area of study, like her mentor’s, is animism, which presupposes that all material phenomena have agency, and that there exists no categorical distinction between the invisible (including the so-called ‘spiritual’) and the material world, any more than there is between the world of humans, animals, and their shared environment. In an influential essay, the British anthropologist Tim Ingold, one of the foremost authorities on animism, has suggested that among hunters and gatherers there is little or no conceptual distance between ‘humanity’ and ‘nature’. ‘And indeed’, he goes on to say, ‘we find nothing corresponding to the Western concept of nature in hunter-gatherer representations, for they see no essential difference between the ways one relates to human and to non-human constituents of the environment.’ Needless to say, such a concept plays havoc with the established dichotomy between ‘humanity’, on the one hand, and ‘nature’ on the other. The very fact that we have a word for ‘nature’ suggests that we do not consider ourselves, as humans, to be fully a part of it; and this disengagement lies at the very root of our current ecological crisis.

In another reading of her story, Nastassja Martin has paid a visit to the underworld, and like Persephone, she has been forced to find her way back. She compares herself with ‘all the creatures that have plunged into the dark and uncharted realms of alterity and have returned metamorphosed.’ This mythical substratum is evident throughout her story, and even in the book’s dedication, which reads: ‘To all creatures of metamorphosis, both here and there, the ‘here’ and ‘there’ standing for the worlds inhabited, respectively, by Martin’s Western readers and the indigenous inhabitants of those circumpolar regions where she has carried out her fieldwork, in Alaska and eastern Siberia. The notion of metamorphosis lies at the heart of her account, and at once invites a radical understanding of animism. As noted, Nastinka has already been named matukha (she-bear) by her Even hosts, before she has her fight with the bear. Afterwards she is medka, ‘marked by the bear’ and therefore half-woman, half-bear. This also means, she is told, that from now on she dreams the bear’s dreams as well as her own. How to accommodate such a belief within a ‘rational’, ‘objective’ or ‘scientific’ Western epistemology? How to do so without placing these very descriptors within quotation marks? Or without taking into consideration Nastinka’s almost inevitable sense of approbation, or even pride, in the acknowledgment by the indigenous community that she is endowed with such qualities?

Her Even friend Vasya tells Nastinka that the bear attacked her because she looked at it, because ‘bears cannot stand to look in the eyes of a human, because they see their own soul there.’ And that moment — in which her eyes locked with the bear’s —keeps returning to her. None of us, at any time, can rule out the possibility, proposed by Martin, that the gaze that passes between two creatures — human or non-human — saves them from themselves ‘by projecting them into the alterity of the being who looks back’, or even that in the instant there might occur a co-mingling or entanglement of souls. In Martin’s words, when she and the bear lock eyes, something is confirmed that the attentive reader might have suspected all along: ‘I know that this encounter was planned. I had marked out the path that would lead me into the bear’s mouth, to his kiss, long ago.’ Why else would she have ‘plunged into battle with the bear . . . like a Fury’? Why else would she have bared her teeth at him? And I wonder why the author leaves it to the third or fourth recap of her encounter with the bear before revealing such a significant detail: ‘He shows me his teeth; he must be afraid. I am frightened too, but as I can’t run away, I imitate him. I show him my teeth. And everything moves into fast-forward. We slam into each other, he knocks me off balance my hands are in his fur he bites my face then my head I can feel my bones cracking I think I am dying but I’m not.’

In reviewing In the Eye of the Wild for the New York Review, Leslie Jamison argues that among other things the book is concerned with translation: ’the desire to translate trauma into meaning, or animal consciousness into legible interior life’, and this latter point lies at the heart of Martin’s project, as I understand it. She translates herself through a painful process of self-interrogation, and in her escape from the madness that lies at the heart of the post-industrial Western world. She mentions it first when quoting Artaud: ‘We have to get out of the insanity our civilisation is creating. But drugs, alcohol, depression and in fine madness and/or death are no solution; we must find something else. This is what I sought in the forests of the Far North, and only partially found it, and it is what I’m still chasing now.’ Martin concedes that her decision to become an anthropologist was, effectively, a form of escape from that insanity, but one which could not so easily be resolved: ‘I learned one thing: no matter how it appears, the world is collapsing simultaneously everywhere. The only difference is that in Tvayan, they live knowingly amid the wreckage.’ I wonder to what extent that is true of other hunter-gatherer communities throughout the world? Reading Joseph Zárate’s harrowing account of the ordeals of the Asháninka and Awajún peoples of Amazonia in their recent fight against oil companies, illegal loggers and gold prospectors, it is hard to think how one might not ‘live knowingly among the wreckage’ when one’s very world is being torn apart before one’s eyes.

During her hospital sojourns and later recuperation, staying first with her mother and then at her own home in the French Alps, Martin realises, four months after her fight with the bear, that she has to return to Tyavan, to her second family, because being ‘here’ will not provide her with the answers she is seeking back ‘there’. She believes in kairos — the exact and appropriate moment for something to occur — and she will claim that her encounter with the bear, too, was a matter of kairos: It happened, as we have seen, because it had to happen, because of who she was, or rather, what she had become. She has to return, because the world ‘there’ has changed her, and she has to uncover her own tracks, to make sense of it all. But her quest is more than intellectual enquiry; it is a headlong plunge into the animism she has set out to both describe and inhabit. Anthropology is not simply something she ‘does’, it constitutes the very essence of who and what she is: and herein lies the paradox, as well as the sadness and beauty of Nastinka’s story. Because she is medka she had to go back to the forest, but she cannot be a part of the Even world any more than she can be a part of her own. And while she can’t stop ‘doing anthropology’ in either place, neither can she stop being the subject of her own ethnography. As she says, it was anthropology that saved her, provided her with an ‘escape route . . . a place where I could express myself in this world, where I could become myself.’ She is caught in between, caught in precisely the reflexive duality she writes of with regard to the myth of Persephone. Thus ‘anthropology’ offers her a kind of release, and a purpose; but it is never quite enough, and it is not an identity that convinces all — or any — of those she lives amongst. She is brought face to face with this hostility most sharply in an encounter with Valyerka, the family member who openly dislikes her — and who tells her: ‘Anthropologist, spy, same thing. Don’t expect anything from me, you’ll not get a word.’

All of which lends particular pathos to the moment when Daria, her Even host and close companion (and surrogate mother), says to her, somewhat mischievously, ‘And how is it done, the anthropology?’ To which Nastinka can only reply, ‘You’re bothering me with your difficult questions’. Eventually she gives it a go: ‘I don’t know how it’s done, Daria. I know how I do it . . . I go close, I am gripped, I move away again or I escape. I come back, I grasp, I translate. What comes from others, goes through my body, and then goes who knows where.’ So she ends, as she promised she would, in uncertainty: but it is an uncertainty of the deepest and most rewarding kind, and because of it the book sings with a strange and vibrant wisdom of its own.

Elsewhere, in her work as ethnographer, Nastassja Martin has chronicled the lives and beliefs of people amongst whom she has worked in Alaska (which she recorded in her first book Les Ames Sauvages). One of these beliefs is related through the words of Clarence, an ‘old Gwich’in wise man’ from Fort Yukon in Alaska, the author’s friend and interlocutor for all the years she lived in his village. According to Clarence, she tells us, there is ‘a boundless realm that occasionally shows at the surface of the present, a dream time which absorbs every new fragment of history as we go on creating them.’ To my understanding, central to this belief is the idea that the quotidian world we inhabit is underpinned by, or overlaps with, another, adjacent realm, which remains largely unseen, hidden behind a veil or membrane, and into which one might accidentally — or voluntarily, through shamanic induction and/or the use of psychotropic drugs — tip or venture. This underpins the belief systems of many indigenous communities, and is a core tenet of animism (which has correspondences in beliefs such as Pantheism or Paganism). We inhabit this world, but it is only one of many, and underlying all of them is that other, invisible or shadow world into which you might slide or tip from time to time when the separating veil is temporarily pulled aside.

It is this ‘boundless realm’ into which we are invited by Irene Solà, the Catalan author of When I Sing, Mountains Dance. In this gem of a book, Solà reinvents the polyphonic novel, with narrators that include, alongside the human occupants, a roe-buck, a dog, a quartet of dead witches, a batch of chanterelle mushrooms, the clouds, even the massif of the Pyrenees itself. And it’s surprising how easily one gets into the swing of it: ‘We arrived with full bellies. Painfully full. Black bellies, burdened with cold, dark water, lightning bolts, and thunderclaps’, claim the clouds at the outset. And here is the dog, Lluna, reflecting on her owner’s sex life: ‘And their sexes grow and turn red and the smell they give off is even better now and more moist . . . and their hands are everywhere and the sounds are everywhere, and I want the smell to get deep inside my muzzle and stay there forever.’ These occasional non-human interventions serve to illustrate that human life is throughly embedded within an animistic universe, wherein every being has as much significance as the next, mushroom, mosquito or man, all of them are bound within the nurturing — but also sometimes terrifying — environment of the forest and the high Pyrenees.

Slowly, the story unfolds, each chapter like a small symphony. The clouds carry a storm, and within the storm a lightning bolt that strikes a man dead. The man, Domènec, has been collecting chanterelle mushrooms and attempting to rescue a calf that was tangled in wire. He leaves behind a widow, Sió, and two small children; daughter Mia, and son Hilari, the latter only two months old. After the villagers take away Domènec’s burnt body and plant a cross in the place the lightning drilled into him, the witches drop by from time to time and piss on the cross. Such is their role; to sully and enliven, to corrupt and to enhance.

The family undergoes another tragedy when, at the age of twenty, Hilari is shot dead by his best friend Jaume, ‘the Giants’ son, all shoulders, small, dark, round head.’ Jaume is also Mia’s lover, and the two of them share naked trysts deep in the forest. Although the shooting is an accident, under the Franco regime Jaume the Giants’ son is deemed a murderer, and goes to prison for five years (had he walked the other way down the mountain into France, he would have faced no such charges). He is so shattered with guilt and shame that he refuses Mia’s prison visits and cannot bring himself to face her on his release from jail, settling into life as an itinerant grill-house chef, a brawler and a drinker; a man on a short fuse. The tale spins on its axis, bringing in a cast of characters and creatures, and the ghosts of men and women who dwell in the forest, among them poor deceased Hilari himself, who now composes poems of solemn and irreverent beauty from beyond the grave. There are other dead roaming the forest too, such as little Palomita whose leg was blown off by a bomb in the civil war — an actual event that took place in January, 1939, when Italian war planes bombed the small town of Garriga, near Barcelona. In the homes around here memories of civil war are never as distant as the years that separate them might suggest, nor are the relics of that war, whether old grenades discovered in a field, or the memories of a son kidnapped by retreating Republicans, and executed ‘just in case’, or of a daughter whose throat is slit as a punishment for emptying a pot of boiling soup onto the heads of some Fascist recruits.

In the original text, Palomita’s account is written in Spanish, which marks it out from the rest of the book, which is in Catalan. She is taken into France but dies in hospital and her ghost returns to the mountains — because it is ‘her place’ — and haunts the mountain forest through which her family fled, and which she has grown to love. Here she occasionally sees the four witches, with whom she frolics, and other lost souls who passed by on the same route into France, like so many of the many thousands of refugees fleeing from the war, and she sees Domènec, Hilari’s father, with his long dirty hair; he says nothing, but eats dirt and digs with his twisted fingernails for roots and worms. Other residents of the forest are more vocal: the chanterelle mushrooms, for example, which ‘have been here always and will be here always . . . Because the spores of one are the spores of all of us. The story of one is the story of us all. Because the woods belong to those who cannot die.’ Eternity, here, is ‘a thing worn lightly’, and the mushrooms proclaim themselves as part of the eternal cycle shared between men and women and beasts and plants.

There is a striking consistency of tone in this short novel, even more apparent on a second reading. I was struck also by what a fine translation it is, as not only does Mara Faye Lethem have to tackle the inventive language Solà uses to represent the forces of nature, and the challenges this gives rise to, but also to ensure that the English version replicates, to some extent, the closely-woven and intimate texture of the Catalan, and to ensure that all the elements — animal, vegetable and mineral — fall into place within the bigger scheme of things. In one chapter we are treated to an outsider’s perspective on the little world ‘up above’ when a hiker from Barcelona turns up, with an idealised picture of the lives led by the locals. How phony and trite he sounds, exclaiming in wonderment: ‘Man, I love walking through these mountains! I just love it so much . . . and the town is lovely as a postcard . . . the butcher’s shop is so authentic. Truly frozen in time.’ Unfortunately we can likely hear our own tourist voices ventriloquised through this character, who has to concentrate if he is to understand the accents of the locals. He is rudely turned away when he asks for food, and cannot understand why he is treated like a stranger, an outsider. But then he is one, and so are we. ‘Life up here is really tragic’, he muses. And he is right.

These mountains and valleys of the Pyrenees lend themselves to strange tales, and at times it is hard to distinguish between what happens and what merely might have happened, as Joan Didion once wrote. Walking not far from the territory of this novel with my daughter a few years ago, on a hot summer’s morning, we came upon a French nun, in full black habit and hiking boots: ‘I have lost my way’, she told us, an utterance that seemed especially poignant, given her calling. Since we were going the same way as her, and knew the path, we accompanied her down the mountain, and she told us the story of how, ten years before, having just turned thirty, she had suddenly found God, had left her high-powered job in PR at a multinational in Paris, had joined the order of the Little Sisters of Jesus and gone to work with the poor and destitute in Palestine. She was on a two-week release, staying at her order’s convent in the Pyrenees. She went out walking every day, she said, whatever the weather. When we parted ways, she had another twenty kilometres to cover before returning to her convent, and when she had gone, it was as if the encounter had been a dream. As it does now, retelling it.

What does Solà’s many-voiced story succeed in telling us, with its lunatics, loafers and wise women, such as Neus, the exorcist, who calls on Mia to get whatever it is out of her house. ‘You no longer belong here,’ she tells the unwanted presence. ‘You have to go. You have to find the path.’ But it is not only the house that is occupied territory: the mountain and the forest also harbour spirits, ghosts, and wild beasts that crave company and understanding, if not something darker. For this is not only a disappearing world in the most obvious sense, where the old traditions and ways of life are dying out, but a world on the brink of cataclysm for all the other reasons with which we are all too familiar.

In Solà’s world too, coincidentally, bears have a role to play, and even though the Pyrenean bear came close to extinction towards the end of the last century, its remaining stock was enhanced by the introduction of the genetically similar Slovenian bear in the 1990s and numbers are now up to around seventy, though they are not to be found as far east as the part of Catalonia where the novel is set, near the town of Camprodon. One of the chapters in Solà’s novel recounts the festival of the bear, that continues to this day in Prats de Molló, just over the French border, and in which the one chosen to dress up as the bear has to leap and shout and make as if to carry off a man like a sheep: ‘Beneath the weight of my immense, stinking body, savage and dirty, he flails . . . A bear has to be ferocious. A bear has to be feared and he must do his job well. Crazed with so much fear and so much rage and so much loneliness and so much humanity. The bear has to forget what he was before and what he will be after and just be a beast, become just the bear and the bear forever.’

So it plays out, this ancient ancestral rite, to celebrate the time of the bear, when the land was shared out between bears and wolves and people, each trepidatious on the other’s patch. The bear in this drama grabs a man’s body, ‘drinks his fear’, grabs a woman, ‘drinks in her panic.’ The bears, we are told, will reconquer the village just as one day they will reconquer the mountain, when the time comes. All of this enacted by the villagers, roaring drunk, their bodies smeared in soot and oil.

When we finally catch up with Jaume, he is working as a cook in a roadhouse bar, and reluctantly tells his story to his boss, Núria. His nickname here, unsurprisingly is ‘the bear’. He tells Núria he’s from the Pyrenees (‘like the bears’), and he’s done time for killing his best friend. He tells the story of how his gun went off by accident when they were hunting, and how his friend died in his arms and it took him hours to carry him down the mountain. How he was sent to prison, how his father died during his second year inside. ‘It’s like a goddamn well. You shouldn’t open the door to memories, because there’s nothing good inside there.’ Which brings to mind a passage from Martin’s book, when she quotes Pascal Quignard approvingly: ‘Freeing ourselves not of the existence of the past but from its ties.’

And, echoing passages from When I Sing, Martin writes: ‘There are other beings lying in wait in my memory; maybe there are also some under my skin, in my bones. This thought is terrifying, because I do not want to be an occupied territory’; and again, after her meeting with the bear, wondering what the ‘next phase might be,’ she writes: ‘Four months and the forest there waiting. The beauty of this thing that happened — happened to me — is that I know everything without knowing anything anymore.’ Thus her experience of the attack and all that follows has also turned into something beautiful, albeit ineffable.

Towards the end of When I Sing, we are swept up in the ineluctable sadness of all that cannot be undone and of an accompanying sense of release, as Mia asserts that being sorry for something and forgiving somebody might happen at the same time, might be two sides of the same coin, and one’s sorrow might co-exist with one’s love, however far that sorrow or that love has had to travel.

‘The story of one is the story of us all’, chant the mushrooms. And as if to seal the uncanny bond that links them, these lines from the final page of Martin’s book could even serve as a summary of Solà’s: ‘There will be one single story, speaking with many voices, the one we are weaving together, they and I, about all that moves through us and that makes us what we are.’

(The text cited by Tim Ingold appears in the essay ‘From trust to domination: an alternative history of human-animal relations’, in Ingold’s book The Perception of the Environment, London: Routledge, 2000.)

In the Eye of the Wild by Nastassja Martin, translated from the French by Sophie R. Lewis, NY: New York Review of Books, 2021.

When I Sing, Mountains Dance by Irene Solà, translated from the Catalan by Mara Faye Lethem, London: Granta, 2022.

This article was first published in Wales Arts Review, on 11 January, 2023.

The untimely departure of Javier Marías

Sad news this week of the death of Javier Marías, for me the most complete novelist of his generation. His trilogy of novels, Your Face Tomorrow, is one of the finest things I’ve ever read. Astonishing that he never won the Nobel. He must have pissed someone off: but then he spent a lifetime doing just that. It was almost a second career, which he perfected over many years in a weekly column for the Spanish newspaper El País, exposing hypocrisy and venality wherever he found them (and he found plenty). He died of pneumonia following on from a bout of COVID. A lifelong smoker, he was often photographed with cigarette in hand, as here.

In an essay from 1995 called ‘What does and doesn’t happen’, Marías wrote:

‘We all have at bottom the same tendency … to go on seeing the different stages of our life as the result and compendium of what has happened to us and what we have achieved and what we’ve realised, as if it were only this that made up our existence. And we almost always forget that … every path also consists of our losses and farewells, of our omissions and unachieved desires, of what we one day set aside or didn’t choose or didn’t finish, of numerous possibilities most of which – all but one in the end – weren’t realised, of our vacillations and our daydreams, of our frustrated projects and false or lukewarm longings, of the fears that paralysed us, of what we left behind or what we were left behind by. We perhaps consist, in sum, as much of what we have not been as of what we are, as much of the uncertain, indecisive or diffuse as of the shareable and quantifiable and memorable; perhaps we are made in equal measure of what could have been and what is.’

The genre of the novel, Marías goes on to say, is able to show, ‘that what was is also of a piece with what was not’. It goes without saying that what never happened is available only to reflection, not to observation. This singular insight has been of invaluable help in my own writing.

On a similar theme, Javier Marías begins Dark Back of Time, his ‘false novel’, with the words: ‘I believe I’ve still never mistaken fiction for reality, though I have mixed them together more than once, as everyone does, not only novelists or writers but everyone who has recounted anything since the time we know began, and no one in that known time has done anything but tell and tell, or prepare and ponder a tale, or plot one.’

Which led me once to ponder: this eternal recounting, this need to tell and tell, is there not something appalling about it – and not only in the sense of whether or not we consciously or intentionally mix reality and fiction? Are there not times when we wish the whole cycle of telling and recounting and explaining and narrating would simply stop – if only for a week, or a day; if only for an hour? The incessant recapitulation and summary and anecdotage and repetition of things said by oneself, by others, to others, in the name of others; the chatter and the news-bearing and the imparting of knowledge and misinformation and the banter and explication and the never ending, all-consuming barrage of blithering fatuity that pounds us from the radio, from the television, from the internet, the unceasing need to tell and make known? And whenever we recount, we inevitably embroider, invent, cast aspersion, throw doubt upon, question, examine, offer for consideration, include or discard motive, analyse, assert, make reference to, exonerate, implicate, align with, dissociate from, deconstruct, reconfigure, tell tales on, accuse, slander or lie.

But nevertheless, if we are anything like Javier Marías, we carry on writing, carry on with the dance, because there is no other. What else could we do? Perhaps for him, at three score years and ten, the time had come to hang up his Olympia Carrera de Luxe (he continued, to the end, to work at an electric typewriter, as though in denial of the digital age). In a similar vein, he once commented that he found it impossible to write fiction set more recently than the 1990s, as though the strictly contemporary world, the world of the new millennium, were simply beyond his remit. The present, with its impossible torrents of information overload, social networking and accompanying identity politics was best left to those born into it.

Marías, whose family background was, like that of so many of his compatriots, overshadowed by the Spanish Civil War and the dictatorship that followed (his father, a respected philosopher, was informed upon by someone he believed to be a friend). As a child, young Javier spent some years in the United States, where he learned to speak perfect English. He published his first novel, Los dominios del lobo (The Domains of the Wolf), aged only nineteen, and later went on to teach for two years at Oxford, where he set his coruscating and brilliant satire of university life, Todos las almas (All Souls). He was also a prodigiously gifted translator from English, with works by Robert Louis Stevenson, Joseph Conrad, Thomas Hardy, W.H. Auden and others – perhaps most notably Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy – among his many translations.

The novel many believe to be his masterpiece, Un corazón tan blanco (A Heart So White), appeared in 1992. Its opening is one that sends shudders through me still:

‘I did not want to know but I have since come to know that one of the girls, when she wasn’t a girl anymore and hadn’t long been back from her honeymoon, went into the bathroom, stood in front of the mirror, unbuttoned her blouse, took off her bra and aimed her own father’s gun at her heart, her father at the time was in the dining room with other members of the family and three guests. When they heard the shot, some five minutes after the girl had left the table, her father didn’t get up at once, but stayed there for a few seconds, paralysed, his mouth still full of food, not daring to chew or swallow, far less to spit the food out on to his plate; and when he finally did get up and run to the bathroom, those who followed him noticed that when he discovered the blood-spattered body of his daughter and clutched his head in his hands, he kept passing the mouthful of meat from one cheek to the other, still not knowing what to do with it. He was carrying his napkin in one hand and he didn’t let go of it until, after a few moments, he noticed the bra that had been flung into the bidet and he covered it with the one piece of cloth that he had to hand or rather in his hand and which his lips had sullied, as if he were more ashamed of the sight of her underwear than of her fallen, half-naked body with which, until only a short time before, the article of underwear had been in contact: the same body that had been sitting at the table, that had walked down the corridor, that had stood there. Before that, with an automatic gesture, the father had turned off the tap in the basin, the cold tap, which had been turned full on.’

I never met Javier Marías, and never felt the desire to, since his novels and essays are so marvellous that the man himself might conceivably have proved a disappointment. But I do recall a story, told me by a friend, that reveals – with dreadful acuity given the way he met his end – something of his character. Marías had been invited to a prestigious international fellowship at a world famous university, which involved lodging in one of the university’s colleges for a couple of months and presenting a series of six lectures. Marías was inclined to accept, but there was one proviso: would he be allowed to smoke in his college room? Unfortunately, he would not: a smoking ban applied to all the university buildings and grounds, without exception. Marías declined the invitation.

He will be much missed, including by those, like me, who only knew him through his works.

A Perambulation with Providence

For some time now, I have been wondering about the idea of Providence. It all started with a quotation from Goethe, about the importance of fully committing oneself when setting out on a new project:

‘The moment one definitely commits oneself, then Providence moves too. All sorts of things occur to help one that would never otherwise have occurred. A whole stream of events issue forth from the original decision which you never dreamed of before.’

While this might sound like a kind of magical thinking to some readers, I do not think it is. I find it quite feasible to believe that once you have decided on a course of action things fall into place around you, so long as the commitment is there. Nonetheless, the notion that something called ‘Providence’ moves with me is the bit I have always wondered about. I have checked it out, of course (I do my prep) and uncovered the definition of Providence, courtesy of Lexico.com as ‘the protective care of God or of nature as a spiritual power’. Meanwhile the OED provides ‘the foreknowing and protective care of a spiritual power, specifically (a) that of God (more fully Providence of God, Divine Providence etc), and (b) that of nature. ‘Nature’ will do, after a fashion, though I honestly can’t think of ‘nature’ as something discrete, extraneous, ‘out there’. It’s the process or dynamic through which we exist. Neither am I crazy about the word ‘spiritual’. It is vague and has too many associations with practices that I find either suspect or presumptuous. But I’m inclined to keep things simple, and will equate ‘God’ with ‘Nature’ here. Providence as the protective care of nature.

I do not pretend to be a philosopher, nor do I have any training in that discipline or dark art, nor am I what might be strictly termed ‘religious’, but I am curious, and as it happens I drop in from time to time on a podcast called The Secret History of Western Esotericism (SHWEP) presented by a man who goes by the name of Earl Fontainelle.

While I am driving up to the Black Mountains from Cardiff early this August Monday morning I listen to an episode, fortuitously titled Providence, Fate, and Dualism in Antiquity. I had not planned this: it was the episode that was next in line.

Given the episode’s title, I am listening out for a definition of Providence, and sure enough, up one pops, or rather up pop several, courtesy of Earl’s interviewee, Dylan Burns, author of Did God Care?: Providence, Dualism, and Will in Later Greek and Early Christian Philosophy.

It would seem, according to Dr Burns, that Providence began its linguistic journey as the prónoia of the Greeks, meaning forethought, and became known in Rome, by Cicero’s day, as providencia. The concept comes up in ancient esoteric texts constantly, I learn, and well into the Middle Ages, where it came to mean the way that God determines Fate, something we would regard as deterministic. This suggests that free will was not a given; we are all subject to some ulterior force that is in a strong sense antithetical to free will, and that is Providence. However, as Dr Burns explains, just because certain things, such as universal laws, are determined by the gods (or God), it doesn’t mean that we are relieved of the responsibility to make the right choices. So, as I understand it, some things are up to chance, others are predetermined by the gods, and yet others can be brought about by the choices made by men and women: that which is up to us. We have free will but should never forget that there are certain things over which we have no control: shit happens.

There’s more, but that’s about as much as I can take in for now. I need to think a little.

Leaving the car at the roadside in Capel y Ffin, I set off up the road towards Gospel Pass, but after 300 metres take a left over a stile, up across a field past a cottage called Pen-y-maes; then follow the path that hugs the hillside below Darren Llwyd, before descending to the covered road just below Blaen-bwch farmhouse.

A quarter of a century ago, when Blaen-bwch was a working farm, I was once nipped on the shin by an over-enthusiastic sheepdog while coming down this lane. I have never forgotten, because it is the only time I have been bitten by a dog. This time there are no dogs, but outside, on the little patch of grass before the house, sit three humans in the lotus posture; two men and a woman. They are wearing loose robes and one of them, the woman, has a wooden bowl in her lap. What is that? Surely not a begging bowl; there’s only a slim chance anyone else will pass this way. Especially on a Monday. Perhaps it’s a gong of some kind. Perhaps it wasn’t made of wood, but bronze. I walked past too quickly to take it in. The meditators are silent, with eyes closed. I feel a wave of slight weirdness as I pass, emanating from one of the meditators, a long, haggard white man, the eldest of the three, who has the look of a self-proclaimed guru. Not hostile weirdness exactly, but a definite vibe of something, and not entirely to do with loving kindness, something more like propriety. It says something like: this is our patch. I can’t help making these evaluations, and am probably wrong, but there you are. When I am thirty metres past the house I stop to tie my bootlace, but really I just want to have another look. The third one, an Asian guy, has his eyes wide open and is watching me; until, that is, he sees that I am watching him, and closes his eyes in the prescribed manner, presumably to continue meditating. I wonder what these people would make of the Providence and free will debate.

The sun is getting warmer. It is forecast to be in the high twenties today, but up here the heat will be easily endurable, thanks to the mountain breeze. I have a hat and suncream, lots of water and a big thermos of spiced tea. I follow the course of the stream, Nant Bwch, and pass the little pool where Bruno the Dog once carried out an infamous atrocity. The spot has gone down in family legend as the pool of the duckling massacre.

A little further up, on my right is the promontory known as Twmpa, or Lord Hereford’s Knob, but I am heading left, or west. I pass a group of five cyclists in their sixties, all men who hail me cheerfully in the accents of the Gwent Valleys. They pass me, one after the other, negotiating the uneven track calling out in my direction: alright butt?; wonderful out yer, innit; lovely day; have a good hike, butt, etc. When they have passed out of sight I sit for a while on the rocks at Rhiw y Fan, overlooking the Wye valley, with the hamlet of Felindre beneath me.

I’d like to fall asleep because I only managed two hours last night, the usual struggle with insomnia until I got up and did some writing around 4.00 and never made it back to bed. But I need to get a shift on, and so head towards the trig point at Rhos Dirion, and there I sit down again, my back propped up against my rucksack and am about to drop off, when I see a very young woman in shorts, tanned legs, athletic build, plaits swinging, who approaches the trig point and proceeds to walk around it in rapid circles, as if she were a wind-up toy, or simply cannot stop moving. I wonder what she is doing out here alone, when I hear voices, crane my head around, and see a small mob of youths approach. From their accents I deduce they are the Essex kids from Maes y Lade residential centre. Two boys in the vanguard of the group address the solitary girl: ‘What are you on, Victoria?’ says one, evidently amazed that she has arrived at the meeting place a good few minutes before any of them. ‘Yeah, what’s Victoria’s secret?’ chimes another lad, the class wit. Victoria, pretty, coy, unspeaking, continues to circle the trig point at speed.

More kids are arriving now, throwing themselves on the ground and bringing out picnic packs and my peaceful interlude has been disturbed, so I move on, westward again, until I come to the track that marks the path of the Grwyne Fawr valley, and I turn south and follow the nascent stream.

I know this path well, love the way it descends through the gradually steepening valley above the reservoir, with the hillsides collapsing in on either side. A little way down I pass a family of ponies. They stop stock still when I take a photograph, as if posing. Then, when I move on, they resume their grazing.

I am getting hungry and stop by the stream, which is beginning to run above ground now, take off my boots. The stream bed is covered with sphagnum, which provides a deliciously soft pillow for my aching feet. A few metres downstream a pony is chomping away at the grass on the bank. She looks over her shoulder at me when I sit down, but does not move away. I feel an intense wave of wellbeing, strip down to my underwear and unpack my meal. I don’t much like eating out in the sun, but there is no shade to be had here, or anywhere near.

After eating, I drink hot chai, and then take myself off to a flat patch of ground. The skeleton of a sheep lies nearby — but is it a sheep, I wonder? Everything has become a little unreal, as though I were watching through a lens in which the colours are both bleached out and stunningly vibrant at the same time, and I cannot decide whether the skeleton belongs to a sheep, or . . . . but I am simply too tired to be bothered by such matters. I greet the skeleton anyway, addressing it as Geoffrey — the first name that comes to mind — and tell it I’m sorry for its loss. I lay out my rain jacket on the grass and lie flat on my back, close my eyes.

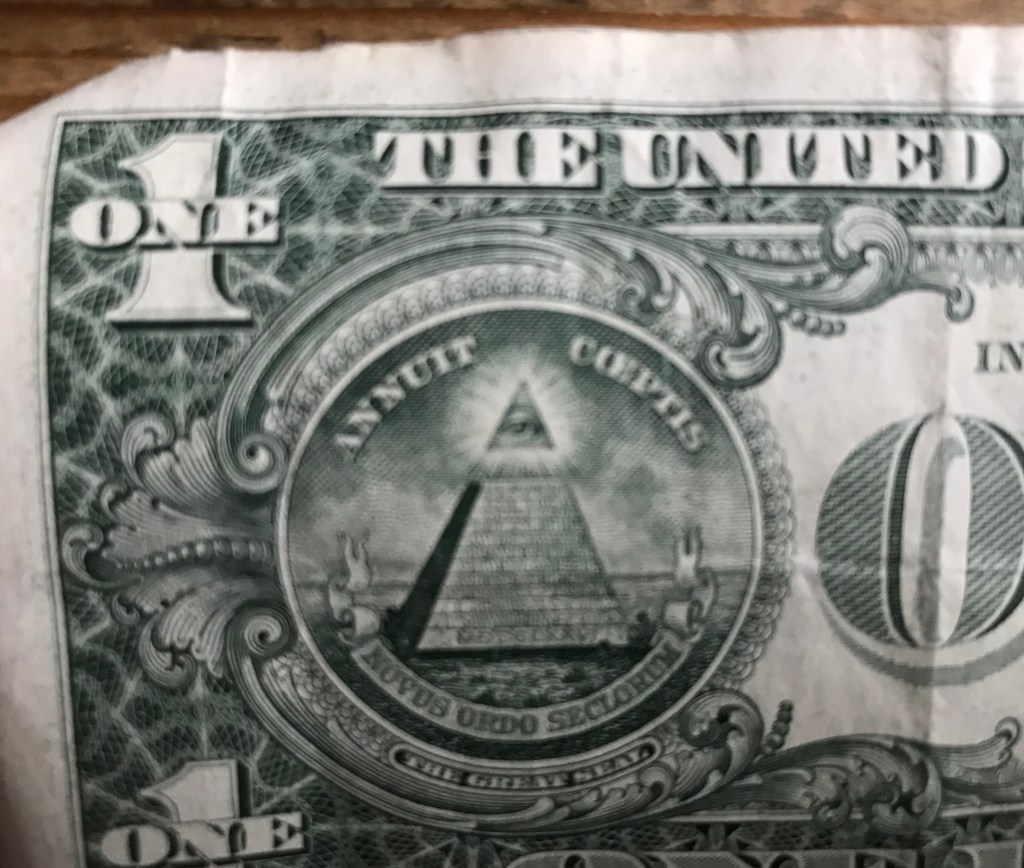

I must have slept for only a few minutes, but I wake with the image imprinted on my consciousness. It is, I know, the Eye of Providence: one of those eyes contained within a triangle that appears universally in religious iconography, from Ancient Egypt onwards. The all-seeing eye of God. The eye is everywhere. It counts every hair on every head and every grain of sand. The eye appeared in late Renaissance art as a symbol of the Holy Trinity. The eye is even printed on the one dollar bill, such is its reach. That eye is monitoring even the most minute financial transactions in the world’s biggest economy.

I am not usually given to conjuring such symbols. I must have invoked it by listening to that podcast. Providence is in the air. And there was its eye, projected onto the inside of my own eyelid when I awoke from the briefest slumber.

I set off down the valley towards the reservoir, passing more ponies on the way. The breeze is a godsend, as it is pretty warm by now. I keep a steady pace and when I reach the dam I veer left at forty-five degrees along a rough track towards the ridge of Tarren yr Esgob, and then take the track south, heading for the blacksmith’s anvil just below Chwarel-y-fan. I am not thinking of anything much at this point, am at that stage of the hike when the mind goes blank, and you simply walk, one foot following the other. And it is then that I notice the flying ants. Hundreds, if not thousands of them, flying in an opaque black cloud just behind my right shoulder. The air is black with them, but none of them are actually bothering me, and I think of them as some kind of diabolical escort — the phrase comes easily to mind after seeing the Eye and all that it entails — as though I were some warrior from an ancient myth come to avenge a terrible murder — perhaps Geoffrey’s? — with a delirious swarm of flying ants at my side. There are none of the insects to my left, the side of the Ewyas Valley; all of them are to the right of me, a dense miasma of evil, or so I suspect. I accelerate, and the cloud accelerates. I stop, and the insect horde hovers closer, a few of them landing on my shoulder and chest, which is no good, that’s not part of the deal, so I brush them away and set off again. I devise a plan to be rid of them. I shall be utterly calm, and rid myself of any trace of stress or inner disquiet. I will be like Don Juan in the Carlos Castaneda books, who was never troubled by flies, not even in Mexico. I don’t know for sure whether that is what does the job, but after another quarter of a mile of serene walking the flying ants drift away, and by the time I arrive at the blacksmith’s anvil, they are gone. I sit on the stone and drink another chai.

The descent leads me down the steep hill below the rocks of Tarren yr Esgob, past the ruins of the monastery of Llanthony Tertia, onto the tarmac lane and back to the car. As I change into trainers for the drive home, a blackbird starts up in the bushes at the roadside. Evening birdsong never was more lovely.

Later, when I am home and getting ready for bed, I pick up the topmost volume of a pile of books that I have to read for a translation competition I am judging. On the cover, to my utmost surprise, and satisfaction, is depicted the Eye of Providence.

A quiet stroll along the ridges

I map out a circular route that begins and ends at the Tabernacl chapel, a third of the way up the Grwyne Fawr valley. I plan a route because I have become more fastidious, as I get older, about leaving clear directions at home, just in case. This notion of following a predetermined route is something quite alien to me, however, and it goes against every fibre of my being to stick to it, not to veer off on subsidiary trails, onto paths that lead nowhere, or else to places I never imagined going. Especially those places, in fact.

And so it is, quite early one morning in late July, that I park the car opposite the chapel and set off up the hillside. I keep to a rhythm, there is nothing original in that, it’s the only way to go, one step leading to another. But that’s why it feels so good. The rhythm of the breath. I pass the badger-faced sheep, which, on this particular farm, have been known to give me the evil eye. Below the Stone of Revenge, I take the lower path, which, after half a mile or so, follows the eastern flank of the Mynydd Du forest. I turn sharp right onto a rough trail up to Bal Bach, and from there the vista opens up over the Ewyas Valley, with Llanthony Priory directly below.

From here I climb to Bal Mawr, and it is now that the green becomes greener, to my eye, at least; a green, as a poet once said, that is close to pain. In the distance, to the south, the Severn Sea is visible. Only on a clear day, and there aren’t so many of those. I stop to drink water, and am greeted by a solitary hiker, a man of around my age, walking in the opposite direction. He is the only human I have seen since leaving the road, and I will not see another for at least three hours, and then at a distance. Which is odd, even for a Tuesday.

A line comes to mind from a book I recently read, which has been playing on my mind. Augustus John’s biographer, Michael Holroyd, writes that John could never be one person, that he didn’t know who he was, that he kept reformulating himself (as an example he says that John kept changing his handwriting). Solitude on these walks often stirs up lightly dormant threads of thought, and I am at once cast adrift on the shores of an old and bitter dispute, brought on by that ‘could never be one person’; whether, indeed, there is such a thing as core identity, reinforced by the continuous tellings and retellings of a discrete and autonomous self, the narrating ‘I’ of its own life story, or whether, rather, we are episodic beings, as the philosopher Galen Strawson proposes, a sequence or series of fleeting ‘selves’ that dissolve and reassemble in different iterations over the course of a lifetime, but which lacks any central unifying narrative that constitutes what we might reasonably think of as a ‘self’. But does it have to either/or? Can I not be the bearer of (or container for) a more transitory and fleeting self and yet retain an underlying constancy, of the kind once called a soul? These ruminations are brought to a close when I spot what looks like a carved tombstone, a rectangular and large white rock, thirty metres below the ridge. I scramble down to inspect it, only to find it is a natural rock, covered by a strange scabby whiteness, some kind of fungus, nothing more.

As I follow a vague track down from Tarren yr Esgob towards the Grwyne Fawr reservoir, a tiny chick adorned with flecks of fluff, peers up at me from the mat-grass. This baby bird is a meadow pipit, and when I stop to take its portrait, I hear the worried chirruping of a parent bird nearby, and so move on.

At the reservoir, the water level is the lowest I have seen it, and although swimming is not encouraged, it certainly isn’t unheard of — and I have swum here myself. No one, though, would be tempted by the water today.

A hundred years ago, when the reservoir was under construction, some of the workers would commute by foot from Talgarth each morning, and back again at night, a walk of around seven arduous miles each way, following the stream north, and descending down Rhiw Cwnstab. My plan was to head the same way, as far as the stream’s source, and then turn left up toward Pen y Manllwyn and Waun Fach, but at this point, having crossed the bridge at the head of the dam, and noticing tracks straight up the hillside toward Waun Fach, I take a short cut. I want to get home before nightfall. The path is very steep, so I stop off to feast on whimberries (or winberries, or billberries, or whortleberries) — but known locally as whimberries — which grow abundantly here. Unfortunately they do not keep well, and reduce to mush very quickly in warm weather, so I don’t take any home.

The summit and environs of Pen y Gadair Fawr is sacred ground, at least for me. I stop to eat my sandwich and gaze in wonder at the majestic lines that sweep down between Pen Trumau and Mynydd Llysiau, allowing the distant shape of Mynydd Troed to slip perfectly between them, as an elegant foot might slip inside a cosmic slipper.

The Mynydd Du forest lies to the east of the ridge, a vast conifer plantation covering over 1,260 hectares that stretches half the length of the valley. For the past fifty years this forest has been a blot on the local landscape. In its recently published ‘Summary of Objectives’, Cyfoeth Naturiol Cymru/Natural Resources Wales claims that it will aim to ‘diversify the species composition of the forest, with consideration to both current and future site conditions, . . . will enhance the structural diversity of the woodland . . . incorporating areas of well thinned productive conifer with a wide age class diversity, riparian and native woodland, natural reserves, long term retentions, and a mosaic of open habitats.’

That is all well and good, and I only hope it comes to pass, because the argument for the planting of native broadleaves has been around for decades now, and in the meantime expanses of the mountain are stripped bare (the term ‘asset strippers’ comes to mind) leaving an ugly void, as the conifers drain the soil of nutrients. I reflect back on a conversation I had with a farmer in the Grwyne Fechan valley last year, who told me how the forestry companies are supposed to plant a percentage of deciduous trees in among the pines, but the approach is tokenistic at best, or else frankly cynical: profit and exploitation of resources is the only serious motive. The landscape I pass to the south of Pen y Gadair Fawr looks and feels like a deserted battlefield. An arboreal graveyard. Nothing much is alive, apart from the few sheep that nibble listlessly at the edge. I feel the usual useless rage, and continue on my way.

Further on, I come across a flattened patch of grass between the ferns, scattered with wrappings from protein and chocolate bars, empty cans of energy drinks, crisp packets, used tissues. I look around. The rubbish covers quite a small area, and there is a breeze, so the litter louts have not long gone. I gather up all the mess and fill the plastic carrier bag that I use as a damp-proofing cushion, and stuff the lot inside my rucksack. Who on earth would leave their trash behind in a place like this? When I round the next hillock I see, in the distance, a group of half a dozen young people crowded around a map that one of them is holding; Duke of Edinburgh participants perhaps? Who else under the age of fifty would use an actual paper map? They look as if they are descending towards the Grwyne Fechan valley road. I think of going and gently explaining things to them, but they are too far away. As I watch, they seem to work out their route, and move on down the hill. I decide not pursue them, and do a stunt as the crazy old man they met up a mountain. It’s wonderful (I want to think) that these kids have an opportunity to walk in these hills, but could they please do so without trashing them? The next day I will ring around a couple of places that provide accommodation for groups of this kind, at Llanthony and Maes y Lade. Neither of them had excursions up in the hills yesterday, they say. I have quite a long chat with the guy from the Maes y Lade Centre, which is run by Essex Youth Service and provides residential holidays for youngsters from that county. He seems genuinely concerned and insists that the kids who come to the centre are taught to respect the local environment. That’s good, I say, and mean it.

Forms of sphagnum have been around for 400 million years, and the soft, absorbent moss has been used widely for poultices, for nappy (or diaper) material by Native Americans such as the Cree, and as insulation by the Inuit. What strikes me most about this little patch of moss or migwyn, however, is the almost luminescent colour, a blend of orange, white and gold that startles in the light of late afternoon, the moss dotted with strange upright stalks, daubs of white fluff attached, resembling candy floss. I think at first it must be sheep’s wool that has adhered to the stems, but it is lighter, fluffier, and more fragile to the touch. I am flummoxed and make a mental note to research my sphagnums.

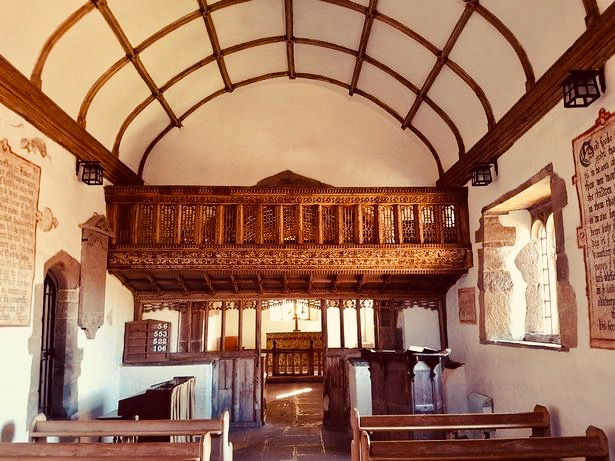

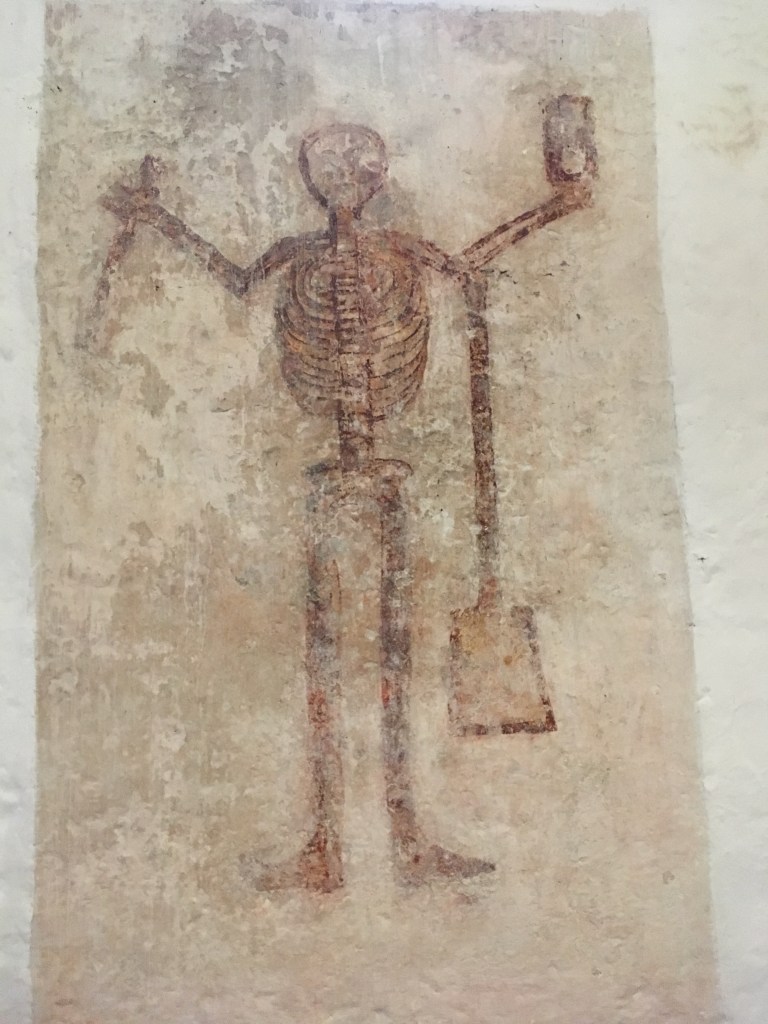

The last stretch of the hike involves a slight ascent up to Crug Mawr, high above Partrishow and its tiny church. Looking west I catch the full contours of the Table Mountain, the iron age fort of Crug Hywel, which lends its name to my native town, Crickhowell, lying beneath it, out of sight. As I sit there in the silence, a red kite appears, glorious in its poise, suspended in impossible stillness high above the trail that forms the Beacons Way, no doubt scanning for any small rodent unwise enough to twitch beneath the ferns. It hangs there for a brief and delicate eternity, barely ruffling a feather, before suddenly swooping, levelling out and gliding at speed a few feet above the ground, then falls upon its prey, which it holds between its vice-like talons and soars away.

The descent towards the valley lane and the chapel is not kind on the knees after these fourteen miles, and I feel the weight of the years. When I get to my car I am joined by an eager young sheepdog, who throws herself into the stream ahead of me, an invitation of sorts. I take off my boots and sit on a rock, my grateful feet soaking in the cold water as the hound frolics briefly in the shallows, gnawing on a stick, before she is called away by a farmer’s whistle. It is evening now, and a cool breeze blows down the valley. I drink the last cup of hot chai from my thermos, smoke a cigarette, and reflect once more on the notion of the self, and core identity, before dismissing the notion entirely, and throwing away the dregs of my tea. My own core identity, if I ever had one, has dissolved into the flickering remnants of the day.

The Open Road

The sun is never so beautiful as on a day when you take to the open road.

For several months, during my travels on foot around southern Europe at the tail end of the 1980s, I carried with me a copy of Jean Giono’s Les Grands Chemins in its French paperback edition, loaned to me by the poet and bouzouki player Hubert Tsarko. Against the odds, my copy shows almost no sign of wear and tear. Sometimes I suspect it is not the book that Hubert loaned me, but I cannot remember buying it again, so have to assume that the same copy has survived the battering of more than thirty years in almost pristine condition. However, that suspicion — that the book is not the same as it was — begins to take on new significance after my pre-ordered copy of The Open Road lands on the doormat with a thump, one day in November, rudely disturbing the slumber of my ancient springer spaniel, Bruno. Re-reading Giono’s novel in another language, thirty years on, it turns out not to be the same book at all, despite the claims of its title.

The book that I remembered was evocative of a lifestyle and a place that I no longer count as mine, but the threads that the story pulls at are lodged deep in memory, and they connect me to some of the wilder places of Europe, as well as to a sense of hearth and home represented in the novel by the fires that the unnamed protagonist keeps burning in his walnut-oil mill on long winter nights, and the climb through the alpine forest towards his final act of sacrifice and betrayal.

A few weeks after drafting the opening paragraphs of this review, Hubert gets in touch with me from Liverpool, in one of his rare and random phone calls, and in answer to my questioning tells me that I returned his copy of Les Grands Chemins in 1989,when he was living in Carrer Sant Just, in the heart of Barcelona’s Gothic Quarter, and that he still has it. In which case, I ask myself, where did my identical copy come from? The truth is that I have no idea.

In case the reader is wondering, this seemingly far-fetched tale is relevant to the writing of this review, as it sets the tone for my relationship with this curious and rather wonderful novel, translated for the first time into English by Paul Eprile and published by New York Review Books, who have been doing a great job in making Giono’s oeuvre available to a new readership, having issued translations of the novels Hill, Melville and A King Alone over the past five years.

I myself attempted a translation of Les Grands Chemins some thirty years ago, but that effort, for better or worse, has disappeared along with so much else. Giono’s narrator is not an educated man; he has apparently served time in prison, and lives from hand to mouth. One of the difficulties of translating the novel lies in finding the right tone and register for the narrator’s constant use of slang and vernacular expressions; and this, more than anything else, was what put paid to my efforts all those years ago. Consequently, my trepidation in waiting for the English version to appear was acute. As the reader will have gathered by now, I have an irrational sense of propriety towards this novel.

Unfortunately, reading the book in translation was a bit like meeting an old and dear friend who has undergone cosmetic plastic surgery, and the result, while by no means a disaster, has left him looking like someone other than himself.

Some novels, perhaps, are more untranslatable than others.

Jean Giono is best known to readers of English as the author of The Man Who Planted Trees, a bittersweet tale written long before there was an environmentalist movement to speak of, and which was made into a popular animated film in 1987. His novel Le Hussard sur le Toit (The Horseman on the Roof ) was also turned into a successful movie, starring Juliette Binoche, but neither of these works really do justice to the deeply felt sense of place and the emotional intelligence of Giono’s work, almost all of which is set in or around the town of Manosque, in the Department of Alpes-de-Haute-Provence, where Giono was born and spent his entire life. Or almost his entire life: in 1914, at the age of nineteen, he was sent off to war, like the vast majority of France’s young men. He trained in the Alpine Infantry and took part in some of the major battles of World War One, including Verdun. Life at the front marked him forever. He was one of the very few survivors of his company to return home, and he became a lifelong pacifist. This was something for which he would be made to suffer after World War Two when he was falsely accused of collaboration with the Nazi occupiers. But that was all later.

Returning to Manosque in 1919, Giono took up the job in a bank which he had held before the war, and began writing. He started with prose poems and moved on to novels. After a few false starts he published Colline (Hill), a strange and intricately patterned tale of rural life, in which the human, animal and vegetable worlds occupying a remote mountain hamlet are seen to be intimately and ineluctably entwined. Colline attracted the attention of some of the big names of Parisian literary life, including André Gide, who paid a visit to find out who this promising young writer was. But Giono was never tempted by life in the metropolis. He bought an old house in an olive grove on the edge of town, and stayed put, dying at home in October 1970 at the age of seventy-five. He thus belongs to a diminishing group of writers who are profoundly and irrevocably associated with a particular place, a defined and circumscribed landscape. ‘Of a piece and of a place’, as Raymond Williams’ protagonist says of his taid, Ellis, in People of the Black Mountains. In fact, re-reading Williams’ last novel immediately after reading Giono has led me to think that this is what Williams would most have liked to be; a writer lodged in a specific locus or habitat, like his namesake Waldo, also a pacifist, who wrote unerringly about a single community in the Preseli hills; or the Italian poet Andrea Zanzotto, like Waldo a village schoolteacher, who spent his entire working life within the region of the Veneto. All three men — Giono, Waldo and Zanotto — spent most of their lives within a small, rural community, and each of them, by focusing on the local and the particular, spoke for the whole of humankind. In The Open Road, Giono’s narrator touches on this very theme when he discusses ‘the things you notice at significant times. For example’, he continues, ‘the footprints of a man who seeks happiness in one spot, with everything taken care of and easy to understand; in a world that following the seasons, seems to follow you; that fulfilling its own destiny, fulfils you . . .’.

Giono has an uncanny skill in evoking the natural world without sentimentalising it: instead he reminds us how our subjective responses, rooted in memory, determine our way of being in the world:

At this time of year, the chestnut sap flows earthward and settles underground. It oozes from all the nicks in the bark that summer has opened wider. It has that hard-to-describe smell of bread dough, of flour mixed with water. A falcon, chased by a cloud of titmice, swoops by low over the trees. The midday warmth spreads like a quilt from my knees to my feet. I’m letting my beard grow, to contend with coldness in general. To live in love or to live in fear: it all comes down to memory.

This seemingly straightforward paragraph can be broken down into four distinct topics, more specifically into three cascading non-sequiturs, which nicely illustrate Giono’s technique. First, the lovely evocation of the sap, oozing from the chestnut tree, and likening the smell of that sap with bread dough. Second, the vision of a bird of prey pursued by a cloud of tiny birds, Third, the weather (warm, but foreshadowing the cold), and finally the curious crowning insight: whether we live in love or in fear, we are constrained by memory. How many novelists would be reckless, or skilled enough to pack so much into a single paragraph?

The extract also serves to show up some of the shortcomings of the translation, because the French says something a little different:

En cette saison, la sève des chatâigniers descend et rentre sous terre. Elle suinte de toutes le égratignures que l’été a élargies dans l’écorce. Elle a cette odeur équivoque de pâte à pain, de farine délayée dans l’eau. Un faucon file en oblique, très bas à travers les arbres, poursuivi par une nuée de mésanges. La chaleur de midi est sur mes pieds et mes genoux comme un édredon. Je laisse pousser ma barbe pour des questions de froid universel. Aimer, vivre ou craindre, c’est un question de mémoire.

First, I would disagree with ‘that hard-to-describe smell of bread dough’, which is a rendering of ‘cette odeur équivoque de pâte a pain’. Unfortunately ‘équivoque’ does not mean ‘hard to describe’, and would more suitably be transcribed as ‘that dubious (or ambivalent, or suspect) smell of bread dough’. And in that puzzling summative sentence, the translator has again changed the meaning of the original: the French is: ‘Aimer, vivre ou craindre, c’est un question de mémoire’, which might be translated as: ‘To love, to live or to be scared, it’s all a question of memory’. These are not terrible misjudgements, more a case of a translator slightly overstepping the mark. If they were isolated incidents, it would matter less, but unfortunately they are not, and this only added to my discomfiture.