The Lady Macbeth Stain Remover

The Guadalajara Book Fair closes today and Blanco is back in Wales. A friend emails from Mexico that they (meaning the assassins referred to in Friday’s post) ‘have still not shot any writers yet, even the bad ones.’ I am relieved, as I would certainly like to go back to the feria del libro, if I am invited. Now that The Vagabond’s Breakfast has been accepted by Argentinian publisher Bajo la Luna, there is a possibility that I might be. For those who read Spanish, an account of Blanco’s performance (and a suitably haggard representation of the author) entitled ‘La mirada del vagabundo/The gaze of the vagabond’, which was hosted quite delightfully by Jorge F. Hernández last Tuesday can be found here.

Although I claimed last during the week that I would not be reading any novels for a year, I cheated, since I was already reading David Enrique Spellman’s Far South when I started the immense The Kindly Ones, and finished it off in Atlanta airport while waiting for my change of plane. Far South is an intriguing experiment in genre writing by a novelist (Spellman is a nom de plume and it is not for me to reveal his identity) who has changed style and theme with each of his four novels. This latest offering is pacey and political, with a fairly representative hard-boiled private dick narrator, subverting the detective novel genre at the same time as subscribing (mostly) to its format. This subversion of a particular mode of telling (or of reading) extends far beyond the book itself: it presumes an invented world – like all fiction – but one which leads into labyrinthine tunnels of consequence, if one takes up the challenge. Spellman is, essentially, questioning the way we invent and receive stories, and his several narrators are all dependent on each other to secure a sequential unreliability. And there is more: as I mentioned in my post from Montevideo, ‘Far South’ is itself a larger project – or collective – consisting of videos and audio clips and installations, to which punters can subscribe and add comments. It might well be a direction that narrative fiction will follow in the near future, particularly well-adapted to e-readers/online reading, as one can switch from written text to videoclip to audio as and when one wishes. I am fascinated to see what ‘Spellman’ comes up with next.

As I still had the onward flight to London to look forward to, I read 24 for 3 by Jennie Walker (another alias, this time for poet and publisher Charles Boyle), which doesn’t really break my commitment as, at 138 sparsely populated pages, it is a short novella or long story, therefore not falling within the prohibited zone. I thoroughly enjoyed 24 for 3, which I finished on the train from Gatwick to Cardiff. It is a delicious story, told with classical economy and a real delight in its subject matter – cricket, sex, parenthood, love – which teases the pleasure points and inspires the reader to drift into secondary or tertiary digression. Surely one of the more neglected benefits of reading, this, the capacity of a piece of writing to inspire creative daydreaming. A gorgeous, elevating read.

I heard the Mexican poet Luis Felipe Fabre read the poem below at an open-air reading in Rosario, Argentina at the end of September. Later that night I went out with him and a few other poets from the festival to a rather poor transvestite show. I never quite got the idea of men dressing up as women. I mean, I don’t get what’s supposed to be funny about it. It seems to particularly affect Latin cultures, which traditionally have a strong macho streak. Perhaps I’m missing something, but if so cannot imagine what it might be. Luis didn’t seem particularly interested either, and we went along because our friends – Los Gays – were going and we were a part of their gang so went along too.

I heard the Mexican poet Luis Felipe Fabre read the poem below at an open-air reading in Rosario, Argentina at the end of September. Later that night I went out with him and a few other poets from the festival to a rather poor transvestite show. I never quite got the idea of men dressing up as women. I mean, I don’t get what’s supposed to be funny about it. It seems to particularly affect Latin cultures, which traditionally have a strong macho streak. Perhaps I’m missing something, but if so cannot imagine what it might be. Luis didn’t seem particularly interested either, and we went along because our friends – Los Gays – were going and we were a part of their gang so went along too.

Luis’ poetry engages with social and political issues of the everyday while drawing back from the more overt banalities of social realism. His poetry collections are Vida quieta (2000), Una temporada en el Mictlán (2003) and Cabaret Provenza (2007). Anyway, here is my translation of the poem he read that midday in Rosario, which gives a flavour of the quotidian presence of violence in Mexico, in which a TV commercial is imagined that reflects the irrepressible logic of consumer culture, flogging a cosmetic product that can wipe away even the most corrosive traces of everyday murder.

Infommercial Luis Felipe Fabre

Señora Housewife: are you sick and tired

of scrubbing night and day

clots of impossible-to-remove blood

from the clothes of all your family?

Do the entrails spattered on the walls of your house

prevent you from sleeping?

Have you found yourself exclaiming like a sleepwalker:

“Out, damned spot, out I say!”?

Now you can buy

Lady Macbeth Stain Remover

and put an end to those viscous nightmares!

Lady Macbeth Stain Remover

is made up from a base of scavenger micro-organisms

that will do your dirty work for you

eliminating

cadaverous remains

without damaging the surfaces to which they are stuck:

scientifically proven!

Señora, you know it: killing

is easy. The difficult part comes later.

But now

Lady Macbeth Stain Remover offers you

an incredible solution that will revolutionize domestic hygiene:

Say goodbye to the trace of brains from your favourite armchair!

Say goodbye to those bloodied rugs!

Take a note now of the number that appears on your screen

or call 01800 666

and receive along with your purchase

a multifunctional applicator and a packet of body bags

absolutely free!

With the Lady Macbeth Stain Remover

you will be able to sleep

like a true queen.

Books and guns in Guadalajara

One of the great pleasures of the Guadalajara Feria del Libro is the spirit of festivity and celebration. Being a Latin affair, the partying is intense and persistent. Fortunately for his readers, Blanco is a restrained sort of chap these days, and since time is limited, would prefer to have a quiet meal with friends rather than to go off on reckless jaunts into the rosy-fingered dawn. However on Tuesday night there was a big do at the house of the Book Fair President, Raúl Padilla, and I went along, easing past the ranks of some very frightening bodyguards into the fabulously well-furnished salón, to enjoy a buffet of epic proportions, and to eavesdrop on the spirited banter of the guests. There is a bit of a bun fight as to who will be invited to be the host country (this year it is Germany’s turn, and next year Chile). There has never been an English-speaking nation, but Ireland are working on a bid for 2013, which might be fun.

Blanco was also able to meet up, quite fortuitously, with two of his favourite Spanish-language writers, both of whom he recently translated for Poetry Wales, the enchanting Cuban Wendy Guerra (who has just brought out a fictionalised account of Anaïs Nin’s time in Cuba called Posar desnuda en La Habana) and the no less gorgeous – and brilliant – Andrés Neuman, whose prize-winning novel Traveller of the Century will be available in English translation in February (published simultaneously by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in the USA and Pushkin Press in the UK).

While talking of favourite writers, I must confess to having met two of my literary heroes, neither of them well enough known in the Anglo-Saxon world, but giants in Latin America. I was introduced to Juan Gelman, the finest Argentinian poet of his generation and a strong contender for the Nobel Prize. Gelman’s is a complicated and tragic story, the essentials of which can be read here, but if you have not read him, please try the excellent translations by Katherine Hedeen and Victor Rodríguez Nuñez in The Poems of Sidney West, published by Salt.

The novelist Sergio Ramírez – who was vice-president of Nicaragua after the Sandinista revolution of 1979, but has since seriously fallen out with the corrupt regime of his onetime-comrade, Daniel Ortega – is perhaps best known for his own powerful and moving account of the revolution, Adiós muchachos but his short stories and a couple of his novels are available in English also. The two of them were enjoying a few tequilas, so I didn’t hang around, but Gelman was very genial, and seemed genuinely pleased when my friend told him I was working on a selected poems of Joaquín Giannuzzi into English (forthcoming with CB Editions).

Strangely enough, I didn’t find out Wednesday night, but the week before the Book Fair there was a mass execution carried out in the city, and the bodies of 26 men, bound and gagged, were found in three trucks only a mile from the Expo Centre where the Book Fair was held (read more here).

Since the Book Fair was celebrating its 25th anniversary the joke was going around that they had chosen to murder 25 and one for luck. Or something. Just to give a signal. It illustrates perfectly the precarious balance of daily life in Mexico today; the contrast between the genuine warmth and hospitality of the Mexican people and the horrific and appalling violence that erupts with such regularity, and which so profoundly colours the outside world’s perception of this fascinating, dangerous and beautiful country.

Dog-throwing in Zapotlanejo and other rare feats

Blanco is renowned for his benevolent nature and willingness to engage in Good Works, especially the healthful encouragement of youth (or what employers insist on calling ‘community engagement’, or even worse, in the university sector ‘impact factors’ – I can barely believe I am saying this) so it will come as no surprise to learn that my visit to the Zapotlanejo High School was a resounding success.

Despite admitting to a certain nervousness in my last post, once the nettle was grasped – or the cactus, more appropriately – everything went swimmingly. First I had to meet the mayor of this small provincial town for handshakes and the obligatory photo session, and received a gift of a history book detailing the beginnings of the Mexican revolution – the war of independence against the Spanish – which was fomented in this region, we set off for the school, where, escorted by two stunningly elegant pupils garbed in regional costume, and to a deafening fanfare of trumpets, such as greets the toreador entering the bullring (I kid you not dear reader) I was introduced to my audience of 16-17 years olds..

The reality was far more pleasant than a corrida, and less bloody. After the usual embarrassing introduction, from the headmaster, I managed to blather on fitfully in Spanish for twenty minutes on the theme of ‘being a writer’ or ‘how I became a writer’, and read a couple of poems, which the English teacher, Carlos, delivered in translation. By which time I felt I’d said enough and opened it up to the floor, rather a dangerous move considering the reluctance of teenagers to be seen to respond positively under these strenuous circumstances. But they reacted marvellously, humouring me – or perhaps even taking pity – by bombarding me with civil, intelligent and even (from one gangster youth near the back) with considerable wit. The most astute question came from a young fellow in a hoodie who asked, more or less, ‘how do you know, when you get to the end of a page, that the words you have chosen are the right ones?’ Most of the kids laughed at him, but I thought it was rather perceptive, and said dammit, that’s what bothers me all the time, jolly good question my lad. So all the kids who had laughed were then booed by the kids who liked the hoodie kid. And so on. We all had a grand time. They had even made a Welsh flag especially for the occasion and some of my new fans posed with me for a picture afterwards.

My hosts insisted on taking me to a nearby Place of Historical Importance, where the first major battle of the war of independence took place, at Puente de Calderón. There, beneath the blazing Jalisco sun, I found out about the details of the conflict, explained to me by Carlos, and when I clambered through the scrub to take a picture of the bridge wondered if there were rattlesnakes – I was assured there were – and wondered yet again at the indefatigable capacity of our species to slaughter one another without respite. I also discovered a new addition to my collection of weird signs, which reads ‘Se prohibe tirar perros’, literally, ‘it is forbidden to throw dogs’, or less literally, to take them to the park and leave them there, a horribly cruel thing to do in any case, but one which encourages the formation of packs of feral dogs who then start to become a menace, as well as shitting everywhere, as Carlos explained. While there, we bumped into the local captain of police, a short but very well-built gentleman with many gold teeth. We fell into conversation and he explained to my hosts about a recent raid that he had led, and which had featured in the news. It involved an organised assault on a drug manufacturing laboratory and resulted in many arrests and a number of deaths. When they had finished, he told us, without any sense of false modesty or exaggeration, the ground outside the laboratory was carpeted with thousands of empty cartridges. He actually seemed a mellow-mannered, thoughtful fellow, but I wouldn’t want to get into a gunfight with him. ‘Mexico is a country of many faces’, said the history teacher, as we walked back to the car.

So, my respects to local culture completed, we set out to eat at a fabulous restaurant where great slabs of meat and half sheep were skewered and cooked around a blazing fire of oak. We ate and drank to the tuneful accompaniment of a mariachi band. Then it was all over and I had to return to Guadalajara to conduct Literary Affairs and to star in an event called La Mirada del Vagabundo or ‘The Gaze of the Vagabond’. It was only when the event had ended and people started to queue up to buy signed copies of said book that I realised I ought to have brought some with me. Oops.

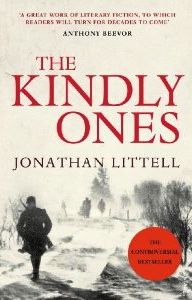

The Kindly Ones

Well, I finished The Kindly Ones on the way here, actually at a little eatery called One Flew South in Atlanta airport, the only place that wasn’t a McDonalds or a Dunkin’ Donuts. The ending was a bit of a let down: I won’t spoil it for you, but it is set in the Berlin zoo as the Russians finally take the city centre. The zoo has taken direct hits from Soviet artillery, all the animals are either wounded and bellowing or else roaming free, and Max, our narrator, gets himself into a bit of a pickle with the two rather odd Thompson and Thomson-style detectives who have been tracking him for half the book, on and off, for the alleged murder of his mother and step-father. Max conducts himself particularly badly, even by SS standards, but then he is a Lieutenant-Colonel by now, as well as quite barking. In fact his last memorable act – and this I must reveal, so stop here if you intend to read the book – is at a medal-giving ceremony in Hitler’s bunker, no doubt the last such ceremony the Führer officiated at. Max has been awarded other medals (he already has an iron cross first class for being bravely shot through the head at Stalingrad) but since he is one of the few senior officers not to have fled Berlin, they think he deserves another one:

Well, I finished The Kindly Ones on the way here, actually at a little eatery called One Flew South in Atlanta airport, the only place that wasn’t a McDonalds or a Dunkin’ Donuts. The ending was a bit of a let down: I won’t spoil it for you, but it is set in the Berlin zoo as the Russians finally take the city centre. The zoo has taken direct hits from Soviet artillery, all the animals are either wounded and bellowing or else roaming free, and Max, our narrator, gets himself into a bit of a pickle with the two rather odd Thompson and Thomson-style detectives who have been tracking him for half the book, on and off, for the alleged murder of his mother and step-father. Max conducts himself particularly badly, even by SS standards, but then he is a Lieutenant-Colonel by now, as well as quite barking. In fact his last memorable act – and this I must reveal, so stop here if you intend to read the book – is at a medal-giving ceremony in Hitler’s bunker, no doubt the last such ceremony the Führer officiated at. Max has been awarded other medals (he already has an iron cross first class for being bravely shot through the head at Stalingrad) but since he is one of the few senior officers not to have fled Berlin, they think he deserves another one:

As the Führer approached me – I was almost at the end of the line – my attention was caught by his nose. I had never noticed how broad and ill-proportioned this nose was. In profile, the little moustache was less distracting and the nose could be seen more clearly: it had a wide base and flat bridges, a little break in the bridge emphasised the tip; it was clearly a Slavonic or Bohemian nose, nearly Mongolo-Ostic. I don’t know why this detail fascinated me, but I found it almost scandalous. The Führer approached and I kept observing him. Then he was in front of me. I saw with surprise that his cap scarcely reached my eyes; and yet I am not tall. He muttered his compliment and groped for the medal. His foul, fetid breath overwhelmed me: it was too much to take. So I leaned forward and bit into his bulbous nose, drawing blood. Even today I would be unable to tell you why I did this: I just couldn’t restrain myself. The Führer let out a shrill cry and leaped back into Bormann’s arms. There was an instant when no one moved. Then several men lay into me.

The effect of this passage is shocking to the reader, in part because up to this point (we are on page 960) everything that has happened has been feasible, if not historically authenticated; Max’s experience of the massacre at Babi Yar, the battle of Stalingrad, the shenanigans among the leadership, the ostracism of Speer by elements of the SS because he wanted to deploy concentration camp inmates as armaments factory workers rather than killing the lot – most everything is the book, other than the character of Max himself, is historically based: and then this marvellous touch, with Max biting Hitler’s nose. I was so surprised I nearly fell off my chair – Demay (or was it Demaine or Deraine?) who was ‘looking after me today’ in One Flew South, was discreet enough not to ask why it took me two hours to eat a portion of sushi – and I truly thought this was an audacious move on the novelist’s part, to have his character bite Hitler’s nose. After all this tension, the massive build up of suffering and terror and slaughter, to have the whole thing brought into close-up: the suggestion that Hitler was far from a perfect example of the Aryan race he sought to perpetuate; that indeed his proboscis indicated Slavic, possibly even more degenerate racial roots, was to Max, ‘scandalous’, serves to explode the tension in a surprisingly effective way. “Trevor-Roper, I know, never breathed a word about this episode, nor has Bullock, nor any of the historians who have studied the Führer’s last days. Yet it did take place, I assure you.” I will not reveal how Max manages to get himself out of this final indiscretion, but it is quite reasonable that he does: and by this point anyway, you just want to get to the end.

Reading Jonathan Littell’s book, however, knowing how slow a reader I am, and the amount of time it has taken me while I might usefully have been employed reading other things has helped bring me to a decision: that for the next year I will only be reading short fiction and poetry. I don’t know if I can stick to it but we’ll see. If nothing else, I will acquire a new acquaintanceship with the short story, which will be fun, and certainly less exhausting.

But right now I must prepare some notes to deliver a talk to a hundred or so Mexican High School kids, on the theme of ‘How I became a writer’. Gulp. Why did I agree to this? I had the choice and could have said no. The truth is, I said it to accommodate the person who asked, at the time a distant and unknown Book Fair official. But what does it take to back out now? In future I think I will cultivate a Beckettian or Pynchonesque silence on matters of self-disclosure – not easy if one is the author of a ‘memoir’. Truly, why put oneself through this kind of thing? But then again, after The Kindly Ones, it’s bound to be a doddle.

Down Mexico Way

Over the next few days, the International Book Fair of Guadalajara will be taking place in Mexico.

Guadalajara is noteworthy for actually inviting numbers of that marginal group in the production of the book, the writer – rather than just the important figures, the publishers and literary agents, for whom these affairs are generally designed. Blanco’s previous visits to Book Fairs (London, twice, and Istanbul, once) apart from being immensely tedious, impressed on him the fact that writers merely represented the messy, grubby end of the publishing process, and if it were at all possible, the agents and publishers would prefer to dispose with them altogether.

Anyhow, the rather novel idea of inviting writers as a major feature of the thing has, contrary to expectations, meant that Guadalajara has gained the reputation of being far and away the most interesting of the world’s book fairs, so that is where Blanco is headed after receiving an invitation from the kind festival administrators back in September. It will involve giving a couple of readings, talking about The Vagabond’s Breakfast (if anyone is interested) and making a visit to a local High School where the students will be waltzed around Blanco’s eerily vacant warehouse of wisdom on literary matters.

Blanco was also told, by an informant who would prefer to remain anonymous, that on arrival at the Book Fair, participants are directed towards a discrete figure who will sell them peyote, the fiercely hallucinogenic recreational drug favoured by Carlos Castaneda’s guru Don Juan, and, with a markedly less spiritual dimension, the late lamented Hunter S. Thompson. This is in order to prevent the punters at the festival from getting hold of the wrong stuff, which I am assured can be very bad for the head. But before anyone starts to fret, or worries that Blanco’s posts from Mexico might become a little, shall we say, confused over the next few days, let me assure you that he is in Guadalajara strictly for professional duties. Indeed, he will leave the recreational side of things to agents and other ne’er-do-wells.

But before packing my toothbrush, just take a look at Mr Scott Pack’s review of Holly Howitt’s unjustly neglected short novel The Schoolboy – better still, buy it yourself. It is, quite simply one of the most impressive first novels (written when the author was 22) that I have read in a long and grizzled career.

But before packing my toothbrush, just take a look at Mr Scott Pack’s review of Holly Howitt’s unjustly neglected short novel The Schoolboy – better still, buy it yourself. It is, quite simply one of the most impressive first novels (written when the author was 22) that I have read in a long and grizzled career.

Radio Bards and an Homuncular Misfit

Few things are quite so guaranteed to make me come out in a rash as a BBC Radio 4 poet blathering on in rhyming couplets while I’m attempting to stir the porridge. This morning I almost fell over the cat as I hurled myself across the kitchen to switch off some dementedly cheerful bard on Saturday Morning Live. I don’t think it was Wendy Cope or Pam Ayres (though I really have no way of discriminating between these people, they are all equally awful). In fact Roger McGough is not much better, or (yawn) Andrew Motion or any of the other so-called interesting poets who jolly along in a British sort of way. I can’t say I enjoy listening to poetry on the radio at all, it’s something about the terribly twee way the BBC goes about presenting the stuff, and the awfully selfconscious way that poets go about reading their work, as though they were reciting from the Bible – or worse, were super-selfconsciously reading from the Bible when pretending NOT to read from the Bible, with all those awful Eliotesque or Churchillian High Rising Tones at the end of lines that actually make me want to barf, make me want to have nothing to do with the stuff. Toxic, it is.

Which might strike you as kind of odd coming from a poet, or one who writes and performs poetry, like myself.

The problem is, I don’t really enjoy poetry readings either. Maybe one in a hundred, and then I absolutely love them. But they are incredibly rare events and I can never predict when it is going to happen. I managed to truly enjoy a joint reading by Derek Walcott and Joseph Brodsky in Cardiff County Hall back at the beginning of the 1990s. I heard an amazing reading by Sharon Olds in Stirling in 2004. I listened to a hugely powerful reading by the revolutionary poet priest Ernesto Cardenal in Nicaragua last year. But granted these were practitioners of excellence (and I have heard Walcott read on other occasions when he has not been that clever). And occasionally I enjoy cosy, informal readings by people who understand that poetry does not have to be a form of display behaviour, such as my friends Patrick McGuinness and Tiffany Atkinson, who both read very well. And a handful of others. But even the ones I like I can only abide in small doses, and even then am not certain I would be able to sit out a full-length radio performance without beginning to fidget.

The truth is, I suppose, that, unfashionably, I prefer to read poetry, in the quiet solitude of my darkened room. I prefer to read it to myself, and imagine its sounds, sometimes out loud, sometimes in my head, but in solitude: just me and the poet. Then, if I don’t like what I’m hearing I can just turn the page, or close the book; something which is not so easily achieved at a poetry reading. Even when the poetry (as at most public Open Mics) is so appallingly bad as to promote immediate self-immolation, it is difficult to leave without drawing attention to oneself. Even propelled by an immediate need to leave the room, to breathe fresh air, if not to commit some terrible violent crime or murder an innocent bystander, one risks the condemnatory glances of audience members (all of whom are aspiring bards themselves). The awful, depressing truth is that every one of the participants at these gloomy affairs believes, at heart, that they are touched by genius. If only others could see it, the world would be a better place. It makes me want to weep, honest: it is such a tragic expression of doomed human endeavour. But still.

David Greenslade is an extraordinary, shamanistic, performer of his work; and a writer of a different order. One of the most startling and memorable readings I can recall was his performance at Hay-on-Wye some years ago, surrounded by an array of glorious vegetables, items of which he would produce from time to time during the course of the event – leek, radish, rhubarb, beetroot, soil-encrusted carrot – in sequential explosions of purposeful poem-making. And his latest book, Homuncular Misfit is, true to form, both bonkers and brilliant. It is, en passant, both an evocation of the alchemical reality of the everyday, as well as a profund, and at times searing account of personal dissolution and nigredo. The sequence of poems relating to the poet/narrator’s adoption by a crow while living at a mysterious Oxfordshire manor house, or indeed a hospice, inhabited by invisible Taoist swordsmen and Chakra cleansers, the kind of place one goes for an ontological enema, is particularly impressive:

David Greenslade is an extraordinary, shamanistic, performer of his work; and a writer of a different order. One of the most startling and memorable readings I can recall was his performance at Hay-on-Wye some years ago, surrounded by an array of glorious vegetables, items of which he would produce from time to time during the course of the event – leek, radish, rhubarb, beetroot, soil-encrusted carrot – in sequential explosions of purposeful poem-making. And his latest book, Homuncular Misfit is, true to form, both bonkers and brilliant. It is, en passant, both an evocation of the alchemical reality of the everyday, as well as a profund, and at times searing account of personal dissolution and nigredo. The sequence of poems relating to the poet/narrator’s adoption by a crow while living at a mysterious Oxfordshire manor house, or indeed a hospice, inhabited by invisible Taoist swordsmen and Chakra cleansers, the kind of place one goes for an ontological enema, is particularly impressive:

. . . For a moment I thought

it might be the same bird that flew

from the glove of Mabon son of Modron

into the mouth of a shepherd

known to Henry Vaughan.

It had appeared as effortlessly as

a piece of clothing I never knew I had

until I bent to pick it up . . . .

. . . Why Crow had come, I couldn’t explain

but it didn’t go away and it did change everything

about that retreat I’d planned, considered

and thought I’d carefully arranged.

As so often occurs in Greenslade’s work, the phenomenal world intercedes in the poet’s life, seeming to take things in hand of its own accord. In his other works vegetables (as we have seen), animals (check out an article of his Zeus Amoeba here), bugs, articles of stationery, random broken things, all break in on the alchemy of the everyday and cast rationality in doubt. This time the crow follows the narrator around whenever he emerges from the house. In one poem, he contacts the RSPB and RSPCA, who both advise to scare the bird off,

But it wouldn’t go. I tried

to be as fierce as a vixen

driving off her cubs.

Defied, the crow would glide into the trees

but return within an hour.

Soon it started waiting near my window.

Unsurprisingly, the bird begins to acquire mythic status in the poet’s mind, taking on the appurtenances of a famous bird from the Mabinogion:

One night, with the hostel

all asleep, I waited mesmerised

beneath the fig tree where

Brân the Blessed perched,

Both as Bendigeidfran

and as Branwen

son and daughter

of their liquid father Llyr,

whose half-speech I now learned.

While soft, slow, pearls of rain

sparkling by kitchen light

fell in glistening strings,

dollops of scintillating guano

puddled freshly opened oysters

on the courtyard’s medieval tiles.

The crow persists, of course, and acquires an increasingly menacing aspect. But we never know how much is in the narrator’s head or how much is (ever) verifiable, because this is the borderland, the zone, the place where weird stuff happens, as Greenslade’s not inconsiderable pack of avid readers have by now learned. Elsewhere the poetry invites favourable comparison with the very best of British poetry currently being published, with a hybrid strain of influence from North American and classical Japanese poets (Greenslade lived in Japan in his twenties and is an ordained Zen monk) as well, of course, as that recurrent dipping into Welsh language and mythology. It might, gentle reader, serve as a fitting stocking-filler for an erudite beloved homunculus of your acquaintance, and is available here.

The first hundred days

WordPress stats informs me that visitor number 10,000 clocked in to the blog on the day of post number 100. Not a bad start. Thanks to you, dear reader, for your support. Tell your friends about the multifarious pleasures of Blanco’s Blog!

Blistering Blue Barnacles!

Buckwheat pancakes with maple syrup and bacon (the latter a rare commodity in the Blanco kitchen these days) all washed down with lashings of coffee made with real beans: what a way to start a Sunday. Not only that, but today’s is the ONE HUNDREDTH (100th) POST SINCE BLANCO BEGAN BLOGGING ON SUNDAY 10TH JULY THIS YEAR. HUZZAH!

Last night we went to see the Spielberg/Jackson production of Tintin (The Adventures of). Mrs Blanco and I were agreed that Captain Haddock (played by Andy Serkis with a magnificent quasi-Scots drawl) and Snowy (aka Milou) the dog stole the show. Tintin is always so damned earnest, but more alarmingly for me, bore an uncanny resemblance to a young Welsh novelist of my acquaintance, and he returned in a more complex hybrid form later, to haunt my dreams, a sort of Tintinesque literary prodigy ploughing the astral plains in search of Ultimate Literary Truth. God help us.

The Tintin stories, for all their being imperialist and racist (charges which no one in their right minds would dispute) created in young readers of my generation – long before the advent of gap years hanging loose on Thai beaches or trekking in the Andes – an ambition to see the world, to become an explorer of worlds. And this is what excited me from an early age. A Dutch student of mine once told me that her grandmother said that children who love the Tintin books will become travellers as adults, and those that don’t won’t. I have a suspicion that something of the kind might be true.

In the meantime I must refrain from embarrassing myself and my dear ones by coming out with exclamations like ‘Great Snakes!’ or ‘Blistering Blue Barnacles!’.

On a quite unrelated theme, I see the film of Owen Sheers’ novel Resistance will be out shortly, with an introductory talk by the author/scriptwriter at Chapter Arts Centre in Cardiff on Saturday 26th November, which I will miss as I am off to Mexico that weekend. In fact I was invited to Mexico along with the same Mr Sheers, who is clearly otherwise engaged – but I share with Owen a childhood fantasy – we grew up a few miles (but two decades) away from each other in the Black Mountains – both playing games that involved charging around in the bracken and ferns evading Nazis, something which I discovered quite by accident while chatting to Owen when we were doing a series of readings together in New York (and where Resistance – the novel – was getting its U.S. launch). What a perennial occupation this Nazi obsession must have been for boys growing up in the decades following World War 2: is it still? I have no idea. But how profoundly the mythology of Nazism has infiltrated our psychological as well as our historical agenda.

And this leads me to the third topic of the day, or the fourth if we include breakfast: the front cover of the Vintage paperback edition of The Kindly Ones by Jonathan Littell.

The picture shows a solitary German soldier walking down a country road in what I imagine is some part of the Soviet Union. If, as the acknowledgement claims, the photo was taken in 1943, the soldier is probably in retreat. In the background and to his side, across a field, are other soldiers, themselves walking alone. There is snow on the ground, and it is either still snowing or else there is a mist. The soldier is walking purposefully, and carrying a rifle over his soldier, so is not in a state of combat. I am fascinated by the photograph, and am trying to work out why. Is it to do with the solitary status of the soldier, knowing as we do the vast numbers of troops involved in the invasion of Russia and in its defence, the huge tallies of the dead that Littell’s protagonist Dr Max Aue recites ad absurdum in the introduction to his story? From what source does the poignancy of this image derive, and why does it affect me so?

The picture shows a solitary German soldier walking down a country road in what I imagine is some part of the Soviet Union. If, as the acknowledgement claims, the photo was taken in 1943, the soldier is probably in retreat. In the background and to his side, across a field, are other soldiers, themselves walking alone. There is snow on the ground, and it is either still snowing or else there is a mist. The soldier is walking purposefully, and carrying a rifle over his soldier, so is not in a state of combat. I am fascinated by the photograph, and am trying to work out why. Is it to do with the solitary status of the soldier, knowing as we do the vast numbers of troops involved in the invasion of Russia and in its defence, the huge tallies of the dead that Littell’s protagonist Dr Max Aue recites ad absurdum in the introduction to his story? From what source does the poignancy of this image derive, and why does it affect me so?

I think the focus on the individual soldier is meant to reinforce Max Aue’s refrain that yes, he is responsible, he did the things which he recites, but that he was an individual in a chain of command, an infinitesimal cog in a massive destructive machine, and his question is, simply, what would you have done?

Or, more succinctly, in Aue’s words, it is “a fact established by modern history that everyone, or nearly everyone, in a given set of circumstances, does what he is told to do; and pardon me, but there’s not much chance that you’re the exception, any more than I was. If you were born in a country or at a time not only when nobody comes to kill your wife and your children, but also nobody comes to ask you to kill the wives and children of others, then render thanks to God and go in peace. But always keep this thought in mind: you might be luckier than I, but you’re not a better person. Because if you have the arrogance to think you are, that’s just where the danger begins.”

The Kindly Ones, fastidiously researched (Littell spent many years on the project and read over two hundred books on the German occupation of the USSR alone) is without doubt one of the most extraordinary novels of recent times: I would place it, together with Roberto Bolaño’s 2666 as one of the two most significant pieces of literary fiction in the 21st century, at least that I’m aware of. 2666 was written in Spanish, obviously, but Jonathan Littell’s book was first published in French as Les Bienveillantes in 2006 and won the Prix Goncourt. It is marvellously translated by Charlotte Mandell, and maybe I will write about it when I have finished (I am not quite half way through its 960 pages, but will stand by my current appraisal nonetheless), but in the meantime I am fascinated by the cover picture, poorly reproduced here, because I could not find a copy of the original, despite searching online through the Keystone/Getty archive, who apparently hold the original. If any readers know anything at all about this photograph, please let me know.

The forlorn penis of Michel Houellebecq

The publication in English of a new novel by Michel Houellebecq, The Map and the Territory, causes me to reflect for a moment on that author, and it occurs to me that whenever I put down a book by Houellebecq I almost immediately forget all about it, until I pick up the next one, which probably says something about how deeply I engage with him as a writer. So what I am about to recount might come as something as a surprise.

Earlier this year I went to a conference: ‘Myth and Subversion in the Contemporary Novel’. I hardly ever attend academic conferences, mostly because they are very tedious affairs, but I felt compelled to go to this one because the title of the conference was so very appealing: who could resist it? Moreover it took place in Madrid, at the Universidad Complutense, in springtime. My hastily written paper was called ‘Promethean Variations: From Wells to Houellebecq’ but it is worth considering what else I might have called it: ‘Michel Houellebecq and the paradigm of eternal youth’ was an early option, and so was ‘The forlorn penis of Michel Houellebecq’. The latter phrase got wedged in my thoughts (there are worse places it might have become wedged) and I could not remember whether I had truly invented it (or dreamed it, rather an awful thought) or had simply read it somewhere and forgotten where. I tried googling the phrase but without success. And yet this title, whether my own or someone else’s, is perhaps most apt. ‘The forlorn penis of Michel Houellebecq’ allows a vicarious and not altogether unfair insight into Houellbecq’s contribution to the erotics of literature – the tragic denouement of his invariably disappointed, frustrated, put-upon, self-absorbed and eventually flaccid male protagonists. And yet, joking aside, what interested me, at least in part, and what impressed me on first reading Houellebecq’s novels – which I came to only recently – was brought about by one of the most dreadful Reality TV shows I have ever had the misfortune to watch, and which I endured with growing consternation one evening in the summer of 2010 while staying at a hotel in Orléans.

The premise of this particular show was unusually inventive, even by the absurd standards of Reality TV. It involved a man in his mid forties – classical Houellebecq material – being set up to meet two ex-girlfriends; one from 25 years earlier, the other, rather ludicrously, from 35 years before, when the protagonists were only 10 years old. Harry – in spite of his years he had retained boyish good looks and a mane of white hair – was not only looking for love, but looking for someone with whom he could parent a fourth child.

Myrtle, his first true love, who went out with him when they were both 19, now lives in Los Angeles, works as a model and does not want children. Laurence, whom he last saw skiing in Chamonix in 1976, works as a gymnastics instructor at a big tourist resort in Turkey. Both of these middle-aged French women are fitness fanatics, trying to retain their youth, while Harry is actually attempting to re-live his youth. The whole premise of the show is like a televisual encapsulation of a Houellebecq novel, without the sex. Because when Harry finally settles on Myrtle and flies over to stay with her in LA she tells him he has to sleep on the sofa, and that she does not want children, definitively, ever. Harry is distraught. He has blown it with Laurence and cannot turn back. Although she is open to the idea of having a child with Harry, she looks her age, and this seems to put Harry off. By choosing Myrtle, who looks much as she did at 19, thanks to her fitness regime and some choice plastic surgery, he feels he can reclaim his youth, in spite of the fact that he has absolutely nothing in common with her and shares none of the same ambitions. Perpetual youth is the sole objective. As Houellebecq puts it in his most successful novel, Atomised: ‘sexual desire is preoccupied with youth’ and, as Isabelle, Daniel’s first wife in The Possibility of an Island remarks: All we’re trying to do is create an artificial mankind, a frivolous one that will no longer be open to seriousness or to humor, which, until it dies, will engage in an increasingly desperate quest for fun and sex; a generation of definitive kids.

Unfortunately, the text of my paper disappeared along with the hard drive of my old macbook (see post for 2 September), so I cannot regale you with the intricate arguments I made in support of my (by no means original) notion that Houellebecq’s fictions are guided by the delusional quest for the fount of eternal youth, and therefore, in some respects, embody the myth of continuous self-renewal symbolised by Prometheus. Nor can I review his new book, not having read it, but I am encouraged by reports that it marks a new departure for an author who was in danger of repeating himself interminably (it also won the Prix Goncourt, which must count for something). But here is a clip of the incorrigible Monsieur Houellebecq, being interviewed by poor old Lawrence Pollard of the ‘Culture Show’, which is apparently a TV programme, not a reggae band. My favourite quote from the interview: ‘As soon as I start talking about my life I start lying straightaway. To begin with I lie consciously and very quickly I forget that I’m lying’. How fortunate, gentle reader, that the same cannot be said of Blanco, blogging bloodhound of Ultimate Truth, or la vérité ultime as we say in France.

Tom Waits, Leonard Cohen, Shane MacGowan, Charles Bukowski and all

Can you do a music review before listening to the music? Let’s see.

Yesterday I received through the post the new CD by Tom Waits, though I have not had the nerve to play it yet. I am not sure I even want to. I do not know quite how I feel about Mr Waits. There is an element of the showman about him that I don’t quite trust.

Unlike Mr Dylan, who can get away with the line “Me, I’m just a song and dance man” because he is so evidently much more, with Waits one might be forgiven for suspecting that such a self-diagnosis would be spot on. The talent is undeniable, and so is the musical range, the technical understanding and the skilful use of genre. The intense and earthy songs of heartbreak and loss on the album Heart attack and Vine once provided me with the perfect music to get miserably drunk to, alone and gloriously despairing, and there have been hundreds of versions of the same songs since. He does slow and sad and he does loud and fast. Both are good, though with the latter he does tend to shout.

I am willing to accept, perhaps, that my difficulty with Tom Waits is that I over-identified with his music for too long, and the problem lies with me rather than with him. And of course I cannot forgive the fact that he was never the real down-and-out he sang about (although he did sing about the lifestyle well). He is linked forever with Bukowski in the mythology I spun about myself in the 1980s (when I was in my twenties) and I cannot read a single line of Bukowski these days, I just find it laughable. Quite apart from his having a face like a jam doughnut. Waits and Bukowski, the dream team (though oddly, Bukowski’s favourite singer-songwriter was Randy Newman, who I liked in my teens but afterwards found rather tame). All these blokes, trying to prove how close to the edge they lived. Maybe I never took either Waits or Bukowski that seriously, they just summed up a lifestyle, but failed to go much deeper.

Shane MacGowan of course, he was another. Maybe he still is. Someone props him up every now and then and he stumbles onto a stage and sings a few songs in an increasingly incomprehensible and strangulated voice, but Christ he had a gift, as a songwriter if nothing else. I met him once, in a bar in Camden. I was always bumping into famous people when I was a drunk. He seemed a decent enough bloke, just fed up with the attention, enjoying a bit of quiet time, I could respect that. His songs with The Pogues became the anthems of my treks on foot across Spain towards the end of the eighties, just as Waits and Dylan had provided the lyrics of my hikes earlier in the decade, across Greece and Italy and France. Roberto Bolaño loved The Pogues too.

And what about Lennie? Leonard Cohen, I mean. I listened to him ardently when I was fourteen, fifteen, then went right off him until I rediscovered his music in my forties. I found out that his best songs can survive multiple replays in ways that Waits’ can never stand up to. And his concert at the Cardiff Arena a few years ago was one of the three best concerts (along with Lila Downs at Peralada and Mariza at Palafrugell) that I have seen in well, the last decade (and that includes two concerts by Dylan himself). I might have a Leonard Cohen song playing at my funeral – yes, I’ve thought about that, such is the dreadful urge towards oblivion, guided by Cohen singing, now which was it, ‘Dance me to the end of love’ or ‘Take this waltz’? I can never decide. Not that I’ll be listening.

But Tommo? He seems very together. Something that you could hardly claim for Cohen, whose biography I read a few years ago and who came across as terminally screwed up, for all the Zen stuff. Or maybe not. Maybe that is just an asinine remark, maybe we are all screwed up, and that part of Cohen’s beauty (and his charm) is that his pain has so indelibly marked him that we are touched, as it were, by the fall-out from his own menagerie of perfume, lace and broken violins, and we can sink into a delectable narcotic haze of suffering by proxy. Certainly the teenage girls in bedsits who were deemed to be his early audience were not alone. This teenage boy was spellbound through long nights with Songs from a Room. And, if I am honest, still can be. He offers just that much more: I’ll call it a flake of the ineffable, because it sounds kind of Cohenesque.

But as for Tom, my internal critic just won’t shut up. Blanco likes the songs, enjoys the ironic melancholy, loves the stuff about drunken sailors and jumping ship to Singapore – and, as an aside, in many of the songs from Rain Dogs, Waits’ best album to date, there are strong personal associations with Thomas Pynchon’s fabulous novel V. which, along with Burroughs’ Cities of the Red Night, was another of Blanco’s travelling companions from the 1980s – but he has problems incorporating Waits into the same illustrious hall of greatness at which Dylan and Cohen hold court. Maybe Blanco will stand corrected after a few listens of Bad as Me. I kind of hope so now. Will report back.