Carnival photos

Here are a few pictures from Wednesday’s carnival in Granada, Nicaragua, where The Tears of Disenchantment (or broken-heartedness) were buried, allegedly.

Brief from Nicaragua

At four in the morning there is a noise of riotous celebration from the nearby square, but I cannot be bothered to make it to the balcony to discover its source. Then there is an hour or so of quiet before the deafening screech of birdsong that signals both the beginning and the end of daylight in the tropics. From the trees circling the park hundreds of birds dance, joust, leap and dive in a frenzied avian fiesta.

Yesterday began with an excursion to the cloud forest volcano of Mombacho – in which we saw howler monkeys

and many birds, including the black headed trogon (trogón cabecinegro, in Spanish) pictured here,

after visiting two coffee plantations, sampling their delicious brews, and witnessing a possum asleep in a bucket

– and concluded with an interminable poetry reading, extremely mixed in quality, but beginning with a single (new) poem by Ernesto Cardenal on the sacking of the museum of Baghdad, and ending with Derek Walcott, again reading a single poem, Sea Grapes. Between these two octogenarian maestros – and with one or two exceptions – a number of distinctly indifferent poets went on for far too long, though I will refrain from mentioning the worst offenders.

Granada is an extraordinary festival, which is growing in importance and recognition, but which needs reining in and the exertion of greater balance in the selection of invited poets. This year, like last, I have met some wonderful individuals, made new friends, and learned a lot, but have also had to listen to far too much bad poetry. Fortunately, Walcott’s Sea Grapes does not fall into this category.

Sea Grapes

That sail which leans on light,

tired of islands,

a schooner beating up the Caribbean

for home, could be Odysseus,

home-bound on the Aegean;

that father and husband’s

longing, under gnarled sour grapes, is

like the adulterer hearing Nausicaa’s name

in every gull’s outcry.

This brings nobody peace. The ancient war

between obsession and responsibility

will never finish and has been the same

for the sea-wanderer or the one on shore

now wriggling on his sandals to walk home,

since Troy sighed its last flame,

and the blind giant’s boulder heaved the trough

from whose groundswell the great hexameters come

to the conclusions of exhausted surf.

The classics can console. But not enough.

Or you can listen to Walcott reading it here.

Briefing from Nicaragua

At four in the morning there is a noise of riotous celebration from the nearby square, but I cannot be bothered to make it to the balcony to discover its source. Then there is an hour or so of quiet before the deafening screech of birdsong that signals both the beginning and the end of daylight in the tropics. From the trees circling the park hundreds of birds dance, joust, leap and dive in a frenzied avian fiesta.

Yesterday began with an excursion to the cloud forest volcano of Mombacho – in which we saw howler monkeys

and many birds, including the black headed trogon (trogón cabecinegro, in Spanish) pictured here,

after visiting two coffee plantations, sampling their delicious brews, and witnessing a possum asleep in a bucket

– and concluded with an interminable poetry reading, extremely mixed in quality, but beginning with a single (new) poem by Ernesto Cardenal on the sacking of the museum of Baghdad, and ending with Derek Walcott, again reading a single poem, Sea Grapes. Between these two octogenarian maestros – and with one or two exceptions – a number of distinctly indifferent poets went on for far too long, though I will refrain from mentioning the worst offenders.

Granada is an extraordinary festival, which is growing in importance and recognition, but which needs reining in and the exertion of greater balance in the selection of invited poets. This year, like last, I have met some wonderful individuals, made new friends, and learned a lot, but have also had to listen to far too much bad poetry. Fortunately, Walcott’s Sea Grapes does not fall into this category.

Sea Grapes

That sail which leans on light,

tired of islands,

a schooner beating up the Caribbean

for home, could be Odysseus,

home-bound on the Aegean;

that father and husband’s

longing, under gnarled sour grapes, is

like the adulterer hearing Nausicaa’s name

in every gull’s outcry.

This brings nobody peace. The ancient war

between obsession and responsibility

will never finish and has been the same

for the sea-wanderer or the one on shore

now wriggling on his sandals to walk home,

since Troy sighed its last flame,

and the blind giant’s boulder heaved the trough

from whose groundswell the great hexameters come

to the conclusions of exhausted surf.

The classics can console. But not enough.

Or you can listen to Walcott reading it here.

Burying poverty and misery

The banner photograph at the top of Blanco’s Blog was taken last year in Granada, Nicaragua at the VII International Festival of Poetry, towards the end of a rather hectic afternoon, on which misery and poverty were cast into Lake Nicaragua, encased in a coffin. Whether or not it worked I am yet to see, but am returning to Granada this weekend, with Mrs Blanco, so may find out. I doubt very much whether Daniel Ortega’s re-election as president will have secured the objectives aimed for by the coffin-carrying devils of last year, pictured here by the Scottish poet Brian Johnstone, but next Wednesday, apparently, Las Lágrimas del desamor or the ‘tears of indifference’ will be done away with and buried. We’ll see how that goes.

But to return to the photo on the blog’s banner, a couple of people have pointed out how the black-masked demon pops up behind the three amigos: he is easy to miss, as he seems an integral part of the background. This picture has haunted me for a long time, and I have practically no memory of taking it; everything was happening very quickly, and I certainly didn’t notice the reaper coming up on the left.

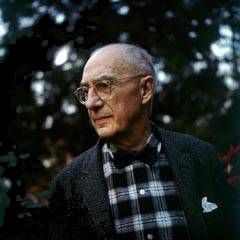

The Festival is held every February in the ancient city of Granada, supposedly the first to be built by the Spanish on the American mainland. Poets are invited from around the world: last year over fifty countries were represented by around a hundred poets. My main interest is concerned with a project I have been working on for the past eighteen months: I am putting together an anthology of contemporary Latin American poetry. This year, apart from the many poets from Latin America who will be attending, there are big names from the English-speaking world: Derek Walcott and Robert Pinsky (as well, of course, as my other Scottish compadre, Tom Pow).

More will follow.

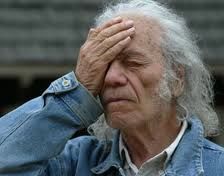

The resentment and insecurity of the poet

Pedro Serrano points me towards an article in the current New York Review of Books, about William Carlos Williams. In it, Adam Kirsch mentions Williams’ sense – whether it was true or not – of having been scorned by Pound, and other acquaintances, writing: “I ground my teeth out of resentment, though I acknowledge their privilege to step on my face if they could.” T.S. Eliot comes in for some particularly harsh judgement: “Maybe I’m wrong”, he wrote to Pound, “but I distrust that bastard more than any writer I know in the world today.”

And yet, Kirsch, reminds us, “If you look at the lingua franca of American poetry today – a colloquial free verse focused on visual description and meaningful anecdote – it seems clear that Williams is the twentieth-century poet who has done most to influence our very conception of what poetry should do, and how much it does not need to do.” It might be added that D.H. Lawrence carried out a very similar seminal role in British poetics.

There is much else that is good to think with in this article, some of it coming from Randall Jarrell, an acute reader of Williams, whom he considered “an intellectual in neither the good nor the bad sense of the word.” I think I know what that means, but maybe not . . .

In his autobiography Williams claims that what drove him to write was anger – somewhat like Cervantes – and his anger was clearly kept warm by his self-doubt and insecurity, his dislike or loathing of certain contemporaries (especially Eliot, of whom he claimed, late in life, to be “insanely jealous”) and his fear that he was not considered an ‘important’ poet.

How terrible the tribulations – real or imagined – of the poet, how fragile the music.

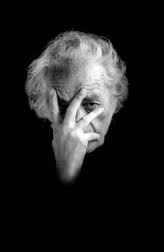

Old Ideas by Leonard Cohen

A new collection of Leonard Cohen songs is a rare event, and Old Ideas, which recycles some familiar themes from the archive, does not disappoint. Throughout Cohen speaks or intones, in his trademark gravelese, not really venturing to follow a tune anymore. Not surprisingly there is a weariness here at times – the guy is 77, after all – reflected in a handwritten scribble in the liner notes: ‘coming to the end of the book / but not quite yet / maybe when we reach the bottom.’ Whether or not this is the last recording by the Magus of Montreal, it has certainly been worth the wait.

If you come to this album expecting all the songs to be of the very highest quality you will be disappointed: they are uneven and the overriding effect is of mood music, Cohen-style, but there are three or four beauties. My favourites are tracks two and three, Amen and Show me the place, in which the singer enacts the role of slave in some religio-sexual psychodrama of the kind we have come to associate almost uniquely with the work of Leonard Cohen. There are also some wonderful, ironic self-references, beginning with the opening lines of the opening song: ‘I love to speak with Leonard / he’s a sportsman and a shepherd’.

‘Amen’ has a familiarity to it, one of those songs you feel you’ve heard before, a song that has always been around . . . I can’t make out whether it is because it bears an uncanny resemblance to a previous Cohen song, and therefore the circling melody and the slow-riding rhythm are so familiar, or simply, as so often with this writer, there is something archetypal in the song itself, as though Cohen were singing from the very bowels of the Judaeo-Christian tradition, brimming over with guilt or nostalgia for things that may or may not have happened. The lyrics alone barely do justice to the slowly churning melody, but I will copy them anyway, and follow it with a clip (unfortunately not from a live performance):

Tell me again

When I’ve been to the river

And I’ve taken the edge off my thirst

Tell me again

When we’re alone and I’m listening

I’m listening so hard that it hurts

Tell me again

When I’m clean and I’m sober

Tell me again

When I’ve seen through the horror

Tell me again

Tell me over and over

Tell me that you want me then

Amen

Poets are liars

So says Björk, in this fascinating interview from 1988, which kind of suggests they – poets – wouldn’t be much good at robbing banks together.

Bank-robber poets

I am currently enjoying the pleasures of the essay and the short ‘occasional piece’, browsing through Roberto Bolaño’s Between Parentheses.What delights await you, gentle reader, between the covers of this excellent collection, if you are unfamiliar with the prose style of this fine writer. But be warned: here you will find speculation of the most dubious kind:

I am currently enjoying the pleasures of the essay and the short ‘occasional piece’, browsing through Roberto Bolaño’s Between Parentheses.What delights await you, gentle reader, between the covers of this excellent collection, if you are unfamiliar with the prose style of this fine writer. But be warned: here you will find speculation of the most dubious kind:

If I had to hold up the most heavily fortified bank in America, I’d take a gang of poets. The attempt would probably end in disaster, but it would be beautiful. (Bolaño, ‘The best gang’).

If I were to rob a bank the last people on earth I would recruit would be poets. They are generally indecisive, opinionated, and almost universally passive aggressive in relation to other poets, and they would therefore certainly take issue with some aspect of poetic discourse (meter, rhyme, assonance, metaphor, what have you) that took precedence over the planning and execution of the job in hand: indeed, once these theoretical differences gained a foothold, there would be no stopping some of them. They would move from poetics to defamatory statements of the most brutal kind, and from there to physical violence. I can assure you, dear reader, that the fiercest disputes occur between individuals when the stakes are really low: academics and poets are prone to the most vitriolic and bloodthirsty of vendettas precisely because the outcome is of practically no interest to anyone else.

This is true, I have hung around with poets and academics for years now, and I’m not sure which group is more inflated in their sense of self-importance, but it’s a close-run thing.

I’m not talking about all poets, of course, or even all academics, and I do hate generalising; but generalisations, like stereotypes, would not exist if there were not a ‘kernel of truth’ to the person, creature or object being generalised or stereotyped. Even if you disagree with the kernel of truth hypothesis on an intellectual level, you almost certainly – if unwittingly – subscribe to it in some aspect of your opinion-forming and decision-making.

But the type of poet or academic I am excusing from this general rule is actually a very small minority. Most of us, whatever we do, and however much we resist the idea, are a part of the herd. And although no one willingly considers himself or herself as part of the herd, the fact is that seen in retrospect, seen from the perspective of a hundred years hence, great swathes of poets (and other writers and artists) will be banded together indiscriminately and one or two exceptions, probably people who are lesser known now, will be isolated as exceptions and therefore bestowed with genius. The typical thinking goes like this: no one wants to think of him or herself as just one of the herd, and everyone thinks that is how it is going to be for everyone else.

We are certain of our uniqueness and individuality, and this would be the first and insuperable problem for Bolaño’s gang of poet-bank robbers, or bank-robber poets: lack of organisational discipline. I may be wrong, but don’t suppose there are many poets in the ranks of the SAS, nor, for that matter have I read any poems by any bank-robber poets. In fact, with all due respect to Roberto, I feel that poets are better suited to working a bank job solo, and probably not planning the job at all, but leaving it all down to fluke and happenstance. In other words, the only way a poet might successfully rob a bank would be alone, and by mistake.

Nicanor Parra at ninety-seven

Two weeks ago the Cervantes prize, Spain’s loftiest literary honour, was bestowed on the Chilean poet Nicanor Parra.

Parra, at ninety-seven years of age, is without doubt the most influential of living South American poets. His career as an eminent physicist (he has been a visiting professor at Oxford and Yale) provided him with a livelihood and immunised him to some extent from the worst abuses of the Pinochet regime. A near-contemporary of Neruda, he considered his more famous compatriot’s poetry to be too flowery, too close for comfort to romantic egotism, and his own ‘antipoetry’ – a term that requires some unpacking – presents a “bleaker vision, prosier rhythms, and starker, surrealist deadpan humor”. By the 1930s Parra was already asserting that what was needed was a vernacular poetry that related to ordinary life and which was accessible to the general public. These ideas, as manifested in Poesia y antipoesia (1954) had a huge impact on poets of a younger generation, especially those who were caught up in the politics of resistance. Parra began writing ‘antipoetry’ because, in his words “poetry wasn’t really working”; there was “a distance between poetry and life”. In a gracious twist, Neruda himself confessed to Parra’s influence on his own later work. It has been claimed, not unreasonably, that Parra’s method derived from his mathematical, relativist background, where he used minimal language and avoided metaphors and tropes in order to address his readers directly. However such assertions almost always sound reductive or cockeyed to me.

Parra’s later work is often a mesh of word association games, intentional cliché and spectacularly straightforward rants about the environment, inequality and corporate corruption. He is a ludic poet, while remaining a poet of intense seriousness. It may well be that his influence will be more lasting than either Neruda or his fellow Nobel laureate, the Mexican Octavio Paz.

Here are a few translations of his work:

OUR FATHER

Our father who art in heaven

Laden with problems of every kind

Your brow knotted

Like any common ordinary man

Don’t worry about us any more.

We understand that you suffer

Because you cannot set your house in order.

We know the Evil One doesn’t leave you in peace

Unmaking everything you make.

He laughs at you

But we weep with you:

Don’t be troubled by his diabolical laughter.

Our father who art where thou art

Surrounded by treacherous angels

Truly: do not suffer any more on our account

You must recognize

That the gods are not infallible.

And that we forgive everything.

(From ‘Bío Bío’)

XXII

CAPITALISM AND SOCIALISM

Nineteenth-century economicrapology

Years before the Principle of Finitude

Neither capitalist nor socialist

But quite the contrary Mr Director:

Intransigent ecologist

We understand by ecology

A socioeconomic movement

Based on the idea of harmony

Of the human species with its environment

Which fights for a ludic life

Creative

egalitarian

pluralist

free of exploitation

And based on communication

And collaboration

Between the big guys & the little guys

MEMORIES OF YOUTH

What’s certain is that I kept going to and fro,

Sometimes bumping into trees,

Bumping into beggars,

I found my way through a forest of chairs and tables,

With my soul on a thread I watched big leaves fall.

But it was all in vain,

I gradually sank deeper into a kind of jelly;

People laughed at my rages,

They started in their armchairs like seaweed carried by the waves

And women looked at me with loathing

Dragging me up, dragging me down,

Making me cry and laugh against my will.

All this provoked in me a feeling of disgust,

Provoked a tempest of incoherent sentences,

Threats, insults, inconsequential curses,

Provoked some exhausting hip movements,

Those funereal dances

That left me breathless

And unable to raise my head for days

For nights.

I was going to and fro, it’s true,

My soul drifted through the streets

Begging for help, begging for a little tenderness;

With a sheet of paper and a pencil I went into cemeteries

Determined not to be tricked.

I kept on at the same matter, around and around

I observed everything close up

Or in an attack of fury I tore out my hair.

In this fashion I began my career as a teacher.

Like a man with a bullet wound I dragged myself around literary events.

I crossed the threshold of private houses,

With my razor tongue I tried to communicate with the audience;

They went on reading their newspapers

Or disappeared behind a taxi.

Where was I to go?

At that hour the shops were shut;

I thought of a slice of onion I had seen during dinner

And of the abyss that separates us from the other abysses.

THE CHRIST OF ELQUI RANTS AT SHAMELESS BOSSES

The bosses don’t have a clue

they want us all to work for nothing

they never put themselves in the shoes of a worker

chop me some wood kiddo

when are you going to kill those rats?

last night I couldn’t sleep again

make water gush from that rock for me

the wife has to go to the gala dance

go find me a handful of pearls

from the bottom of the sea

if you please

then there are others who are

even bigger wankers

iron me this shirt shitface

go find me a tree from the forest fuckwit

on your knees asshole

. . . go check those fuses

and what if I get electrocuted?

and what if a stone lands on my head?

and what if I meet a lion in the forest?

aw hell!

that is of no concern to us

that doesn’t matter in the least

the really important thing

is that the gentleman can read his newspaper in peace

can yawn just when he pleases

can listen to his classical music to his heart’s content

who gives a shit if the worker cracks his skull

if he takes a tumble

while soldering a steel girder

nothing to get worked up about

these half-breeds are a waste of space

let him go fuck himself

and afterwards it’s

I don’t know what happened

you can’t imagine how bad I feel Señora

give her a couple of pats on the back

and the life of a widow and her seven chicks ruined

FROM ‘NEW SERMONS AND TEACHINGS OF THE CHRIST OF ELQUI’

XXXII

Those who are my friends

the sick

the weak

the dispirited

those who don’t have a place to lie down and die

the old

the children

the single mothers

– the students, not because they are troublemakers –

the peasants because they are humble

the fishermen

because they remind me

of the holy apostles of Christ

those who did not know their father

those who, like me, lost their mother

those condemned to a perpetual queue

in so-called public offices

those humiliated by their own children

those abused by their own spouses

the Araucanian Indians

those who have been overlooked at some time or other

those who can’t even sign their names

the bakers

the gravediggers

my friends are

the dreamers, the idealists who

like Him

surrendered their lives

to the holocaust

for a better world

ROLLER COASTER

For half a century

Poetry was the paradise

Of the solemn fool.

Until I came along

And set up my roller coaster.

Go on up, if you want.

It’s not my fault if you come down

Bleeding from your mouth and nose.

Translations by Richard Gwyn, first published in Poetry Wales, Vol 46, No 3 Winter 2010-11.

Radio Bards and an Homuncular Misfit

Few things are quite so guaranteed to make me come out in a rash as a BBC Radio 4 poet blathering on in rhyming couplets while I’m attempting to stir the porridge. This morning I almost fell over the cat as I hurled myself across the kitchen to switch off some dementedly cheerful bard on Saturday Morning Live. I don’t think it was Wendy Cope or Pam Ayres (though I really have no way of discriminating between these people, they are all equally awful). In fact Roger McGough is not much better, or (yawn) Andrew Motion or any of the other so-called interesting poets who jolly along in a British sort of way. I can’t say I enjoy listening to poetry on the radio at all, it’s something about the terribly twee way the BBC goes about presenting the stuff, and the awfully selfconscious way that poets go about reading their work, as though they were reciting from the Bible – or worse, were super-selfconsciously reading from the Bible when pretending NOT to read from the Bible, with all those awful Eliotesque or Churchillian High Rising Tones at the end of lines that actually make me want to barf, make me want to have nothing to do with the stuff. Toxic, it is.

Which might strike you as kind of odd coming from a poet, or one who writes and performs poetry, like myself.

The problem is, I don’t really enjoy poetry readings either. Maybe one in a hundred, and then I absolutely love them. But they are incredibly rare events and I can never predict when it is going to happen. I managed to truly enjoy a joint reading by Derek Walcott and Joseph Brodsky in Cardiff County Hall back at the beginning of the 1990s. I heard an amazing reading by Sharon Olds in Stirling in 2004. I listened to a hugely powerful reading by the revolutionary poet priest Ernesto Cardenal in Nicaragua last year. But granted these were practitioners of excellence (and I have heard Walcott read on other occasions when he has not been that clever). And occasionally I enjoy cosy, informal readings by people who understand that poetry does not have to be a form of display behaviour, such as my friends Patrick McGuinness and Tiffany Atkinson, who both read very well. And a handful of others. But even the ones I like I can only abide in small doses, and even then am not certain I would be able to sit out a full-length radio performance without beginning to fidget.

The truth is, I suppose, that, unfashionably, I prefer to read poetry, in the quiet solitude of my darkened room. I prefer to read it to myself, and imagine its sounds, sometimes out loud, sometimes in my head, but in solitude: just me and the poet. Then, if I don’t like what I’m hearing I can just turn the page, or close the book; something which is not so easily achieved at a poetry reading. Even when the poetry (as at most public Open Mics) is so appallingly bad as to promote immediate self-immolation, it is difficult to leave without drawing attention to oneself. Even propelled by an immediate need to leave the room, to breathe fresh air, if not to commit some terrible violent crime or murder an innocent bystander, one risks the condemnatory glances of audience members (all of whom are aspiring bards themselves). The awful, depressing truth is that every one of the participants at these gloomy affairs believes, at heart, that they are touched by genius. If only others could see it, the world would be a better place. It makes me want to weep, honest: it is such a tragic expression of doomed human endeavour. But still.

David Greenslade is an extraordinary, shamanistic, performer of his work; and a writer of a different order. One of the most startling and memorable readings I can recall was his performance at Hay-on-Wye some years ago, surrounded by an array of glorious vegetables, items of which he would produce from time to time during the course of the event – leek, radish, rhubarb, beetroot, soil-encrusted carrot – in sequential explosions of purposeful poem-making. And his latest book, Homuncular Misfit is, true to form, both bonkers and brilliant. It is, en passant, both an evocation of the alchemical reality of the everyday, as well as a profund, and at times searing account of personal dissolution and nigredo. The sequence of poems relating to the poet/narrator’s adoption by a crow while living at a mysterious Oxfordshire manor house, or indeed a hospice, inhabited by invisible Taoist swordsmen and Chakra cleansers, the kind of place one goes for an ontological enema, is particularly impressive:

David Greenslade is an extraordinary, shamanistic, performer of his work; and a writer of a different order. One of the most startling and memorable readings I can recall was his performance at Hay-on-Wye some years ago, surrounded by an array of glorious vegetables, items of which he would produce from time to time during the course of the event – leek, radish, rhubarb, beetroot, soil-encrusted carrot – in sequential explosions of purposeful poem-making. And his latest book, Homuncular Misfit is, true to form, both bonkers and brilliant. It is, en passant, both an evocation of the alchemical reality of the everyday, as well as a profund, and at times searing account of personal dissolution and nigredo. The sequence of poems relating to the poet/narrator’s adoption by a crow while living at a mysterious Oxfordshire manor house, or indeed a hospice, inhabited by invisible Taoist swordsmen and Chakra cleansers, the kind of place one goes for an ontological enema, is particularly impressive:

. . . For a moment I thought

it might be the same bird that flew

from the glove of Mabon son of Modron

into the mouth of a shepherd

known to Henry Vaughan.

It had appeared as effortlessly as

a piece of clothing I never knew I had

until I bent to pick it up . . . .

. . . Why Crow had come, I couldn’t explain

but it didn’t go away and it did change everything

about that retreat I’d planned, considered

and thought I’d carefully arranged.

As so often occurs in Greenslade’s work, the phenomenal world intercedes in the poet’s life, seeming to take things in hand of its own accord. In his other works vegetables (as we have seen), animals (check out an article of his Zeus Amoeba here), bugs, articles of stationery, random broken things, all break in on the alchemy of the everyday and cast rationality in doubt. This time the crow follows the narrator around whenever he emerges from the house. In one poem, he contacts the RSPB and RSPCA, who both advise to scare the bird off,

But it wouldn’t go. I tried

to be as fierce as a vixen

driving off her cubs.

Defied, the crow would glide into the trees

but return within an hour.

Soon it started waiting near my window.

Unsurprisingly, the bird begins to acquire mythic status in the poet’s mind, taking on the appurtenances of a famous bird from the Mabinogion:

One night, with the hostel

all asleep, I waited mesmerised

beneath the fig tree where

Brân the Blessed perched,

Both as Bendigeidfran

and as Branwen

son and daughter

of their liquid father Llyr,

whose half-speech I now learned.

While soft, slow, pearls of rain

sparkling by kitchen light

fell in glistening strings,

dollops of scintillating guano

puddled freshly opened oysters

on the courtyard’s medieval tiles.

The crow persists, of course, and acquires an increasingly menacing aspect. But we never know how much is in the narrator’s head or how much is (ever) verifiable, because this is the borderland, the zone, the place where weird stuff happens, as Greenslade’s not inconsiderable pack of avid readers have by now learned. Elsewhere the poetry invites favourable comparison with the very best of British poetry currently being published, with a hybrid strain of influence from North American and classical Japanese poets (Greenslade lived in Japan in his twenties and is an ordained Zen monk) as well, of course, as that recurrent dipping into Welsh language and mythology. It might, gentle reader, serve as a fitting stocking-filler for an erudite beloved homunculus of your acquaintance, and is available here.

Lucifer in Starlight

I was flicking through web pages, looking for nothing in particular, which in ordinary life tends to invoke a receptive and often interesting state of receptivity. Moreover I was tired, and therefore probably susceptible to sentiments that I might normally guard against (but probably do not).

Anyhow, I stumble across a poem by David St. John, not a poet I remember having read before, and fell straight for it: a musical poetry of desire, of neglect, of forgetting – in which nothing sounds quite right: the man at the party is actually saying he prefers Athens to Rome; the woman whose vest “belled below each breast”(?); the disconnect between what he is saying of Rome and what is dancing urgently beneath the text, tugging at memory. What is going on here, as the narrator jumps from place to place, zone to emotional zone? And who is he? Yet I read on, lulled by the easy rhythms as the lines spilled across the page through various absurdities (“it was here I’d chosen / To live when I grew tired of my ancient life / As the Underground Man”) – Velvet Underground?

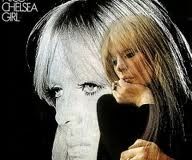

And then the extraordinary fluidity of the lines that follow the arrival in his apartment at 3.00 a.m. of Nico, with her sunken eyes, Marlene Dietrich vowels, not only in her Velvets persona but more specifically as the lowing chanteuse of the Chelsea Girls album, junk-queen heroine of my adolescence, her somber drone exciting me with visions of decadent and lonely immolations in seedy hotel rooms, dark nights of impossible desire, and the soul-barren broken wanderlust which would soon become mordant reality, and who:

Pulled herself close to me, her mouth almost

Touching my mouth, as she sighed, “Look … ,”

And deep within the pupil of her left eye,

Almost like the mirage of a ship’s distant, hanging

Lantern rocking the waves,

I could see, at the most remote end of the receding.

Circular hallway of her eye, there, at its doorway,

At the small aperture of the black telescope of the pupil,

A tiny, dangling crucifix –

Silver, lit by the ragged shards of starlight, reflecting

In her as quietly as pain, as simply as pain …

So, I will copy the poem in full, after all, although I have to keep it in italics, otherwise WordPress will re-align the text. The citation is from the eponymous poem by Meredith (1828-1909) which can be found here, the opening lines of which are: ON a starr’d night Prince Lucifer uprose. / Tired of his dark dominion swung the fiend / Above the rolling ball in cloud part screen’d, / Where sinners hugg’d their spectre of repose.

Lucifer in Starlight

Tired of his dark dominion …

—George Meredith

It was something I’d overheard

One evening at a party; a man I liked enormously

Saying to a mutual friend, a woman

Wearing a vest embroidered with scarlet and violet tulips

That belled below each breast, “Well, I’ve always

Preferred Athens; Greece seems to me a country

Of the day—Rome, I’m afraid, strikes me

As being a city of the night … ”

Of course, I knew instantly just what he meant—

Not simply because I love

Standing on the terrace of my apartment on a clear evening

As the constellations pulse low in the Roman sky,

The whole mind of night that I know so well

Shimmering in its elaborate webs of infinite,

Almost divine irony. No, and it wasn’t only that Rome

Was my city of the night, that it was here I’d chosen

To live when I grew tired of my ancient life

As the Underground Man. And it wasn’t that Rome’s darkness

Was of the kind that consoles so many

Vacancies of the soul; my Rome, with its endless history

Of falls … No, it was that this dark was the deep, sensual dark

Of the dreamer; this dark was like the violet fur

Spread to reveal the illuminated nipples of

The She-Wolf—all the sequins above in sequence,

The white buds lost in those fields of ever-deepening gentians,

A dark like the polished back of a mirror,

The pool of the night scalloped and hanging

Above me, the inverted reflection of a last,

Odd Narcissus …

One night my friend Nico came by

Close to three a.m.—As we drank a little wine, I could see

The black of her pupils blown wide,

The spread ripples of the opiate night … And Nico

Pulled herself close to me, her mouth almost

Touching my mouth, as she sighed, “Look … ,”

And deep within the pupil of her left eye,

Almost like the mirage of a ship’s distant, hanging

Lantern rocking with the waves,

I could see, at the most remote end of the receding,

Circular hallway of her eye, there, at its doorway,

At the small aperture of the black telescope of the pupil,

A tiny, dangling crucifix—

Silver, lit by the ragged shards of starlight, reflecting

In her as quietly as pain, as simply as pain …

Some years later, I saw Nico on stage in New York, singing

Inside loosed sheets of shattered light, a fluid

Kaleidoscope washing over her—the way any naked,

Emerging Venus steps up along the scalloped lip

Of her shell, innocent and raw as fate, slowly

Obscured by a florescence that reveals her simple, deadly

Love of sexual sincerity …

I didn’t bother to say hello. I decided to remember

The way in Rome, out driving at night, she’d laugh as she let

Her head fall back against the cracked, red leather

Of my old Lancia’s seats, the soft black wind

Fanning her pale, chalky hair out along its currents,

Ivory waves of starlight breaking above us in the leaves;

The sad, lucent malevolence of the heavens, falling …

Both of us racing silently as light. Nowhere,

Then forever …

Into the mind of the Roman night.

Hunger for Salt

from left to right, Blanco’s stuntman and sometime collaborator Richard Gwyn, Carlos Pardo, Juan Dicent and Niels Frank.

A post from Pablo Makovsky, director of the Rosario International Poetry Festival, and a video of us reading ‘Hunger for Salt’ in English and Spanish (translation by Jorge Fondebrider). Also on the festival website a very good quality recording of our rendition of ‘Dusting’.

Hunger for Salt

Will I remember you in the dull yellow light,

as a fish that enters my mouth, as a virus

that enters my blood, as a fear that enters my belly?

Will I remember you as a catastrophe

tearing between my legs, fine teeth slitting my lip,

tongue touched with salt my tongue was crazy for?

You never confessed to those little thefts:

my mother’s ring, the statue from Knossos,

the locket I kept for the hair of children

we never had. I see you, come to steal my bones,

small teeth so white, a necklace of coloured stones,

clams and mussel shells around your waist,

an ankle chain of emeralds. But now you have gone

back to the sea, I can forgive your cruelty,

your violent moods, your plots of revenge,

remembering instead the brush of your skin

on mine, the way you looked at me that afternoon

in the sea cave, gulls clamouring outside,

a crowd of angry creditors in a world otherwise

gone terribly quiet. And you, nestling in

the white sand, caught in the nets I wove

with a devout sobriety, turned utterly to salt.

Hambre de sal

¿Te recordaré en la luz insulsa y amarilla,

como a un pez que me entra en la boca, como un virus

que me entra en la sangre, como un miedo que me entra en la panza?

¿Te recordaré como una catástrofe

desgarrándome entre las piernas, dientes minúsculos que me hienden el labio,

lengua tocada con sal por la que mi lengua estaba loca?

Nunca reconociste esos pequeños robos:

el anillo de mi madre, la estatua de Knosos,

el medallón que yo guardaba para el cabello de los chicos

que nunca tuvimos. Te veo, ven a robar mis huesos,

dientecillos tan blancos, un collar de piedras coloridas,

valvas de almejas y mejillones alrededor de tu talle,

una cadena de esmeraldas en el tobillo. Pero ahora te has ido

de vuelta al mar. Puedo perdonar tu crueldad,

tus humores violentos, tus tramas de venganza,

recordando en lugar de eso el roce de tu piel

sobre la mía, el modo en que me viste aquella tarde

en la cueva marina, las gaviotas chillando afuera,

una multitud de airados acreedores en un mundo distinto,

vuelto terriblemente silencioso. Y tú, anidando

en la arena blanca, atrapada en las redes que tejí

con devota sobriedad, por completo convertida en sal.

From Being in Water (Parthian, 2001).