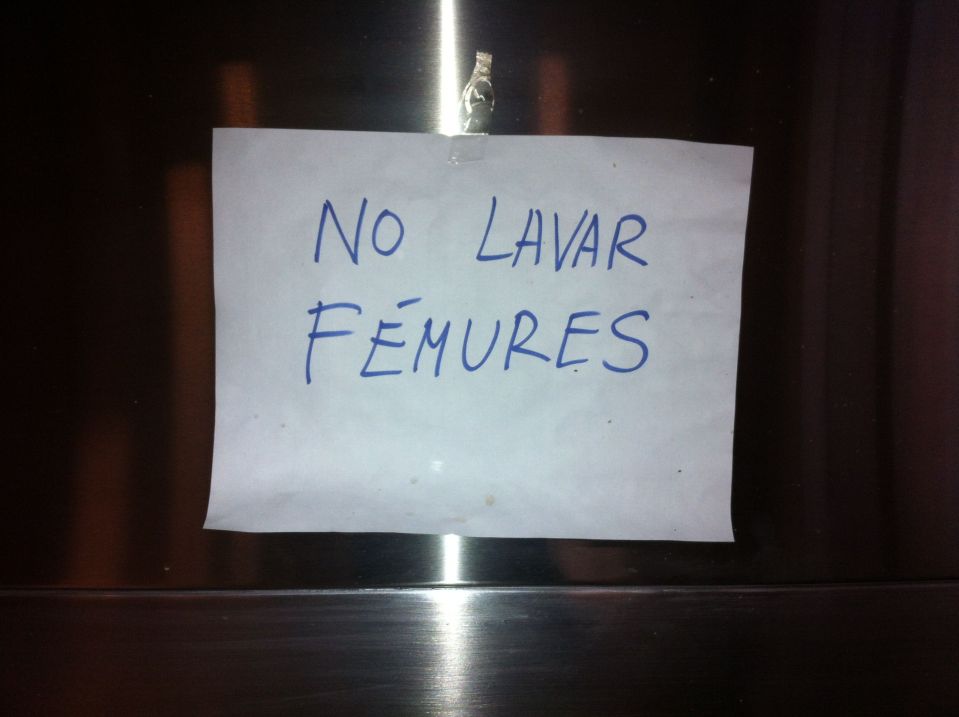

Don’t wash your femurs here

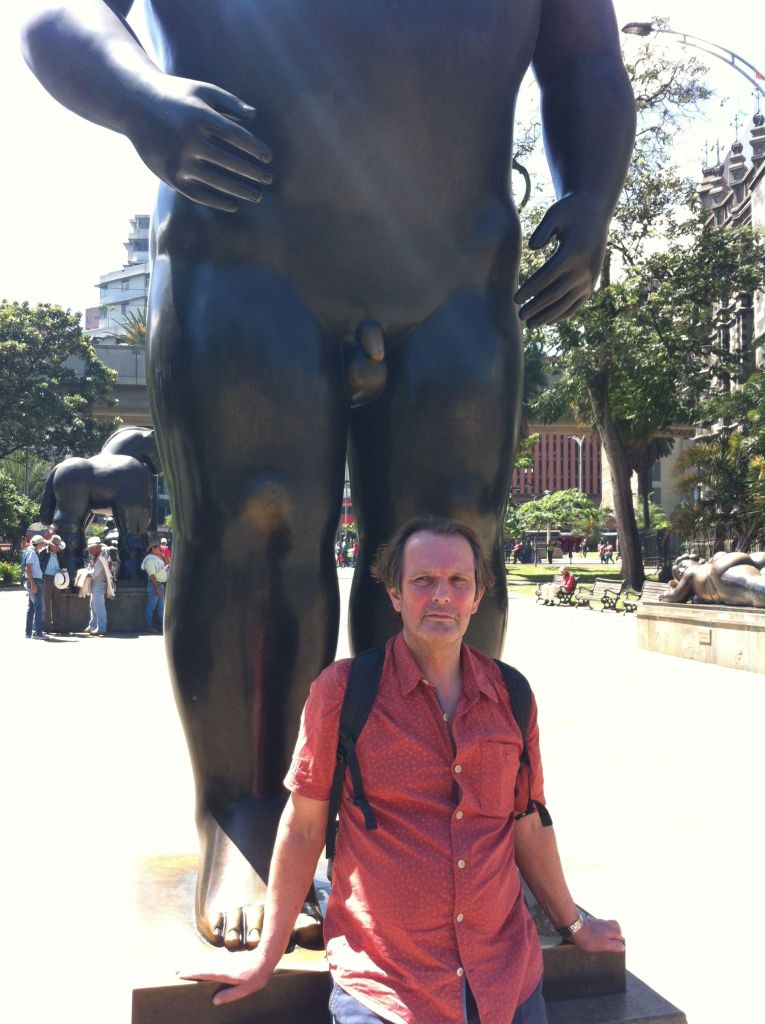

Why would anyone leaving a sign above a sink with a warning that femurs should not be washed? Probably only in an archaeology laboratory at the University of the Andes in Bogotá. I was visiting the labs with two archaeologists at the university, Elizabeth and Luis, who showed me some of the work they are undertaking with human remains from the pre-Columbian period: burial chambers, sarcophagi and what not. They also showed us around the Museo de Oro, a fabulous museum containing more gold than anyone will ever need. I am not big on gold, but some of the craftsmanship of the work was extraordinary. I was more struck by the section on shamanism, the images of animal transformation and artefacts associated with the use of hallucinogenic plants, with which many of the indigenous people of the region have been closely associated.

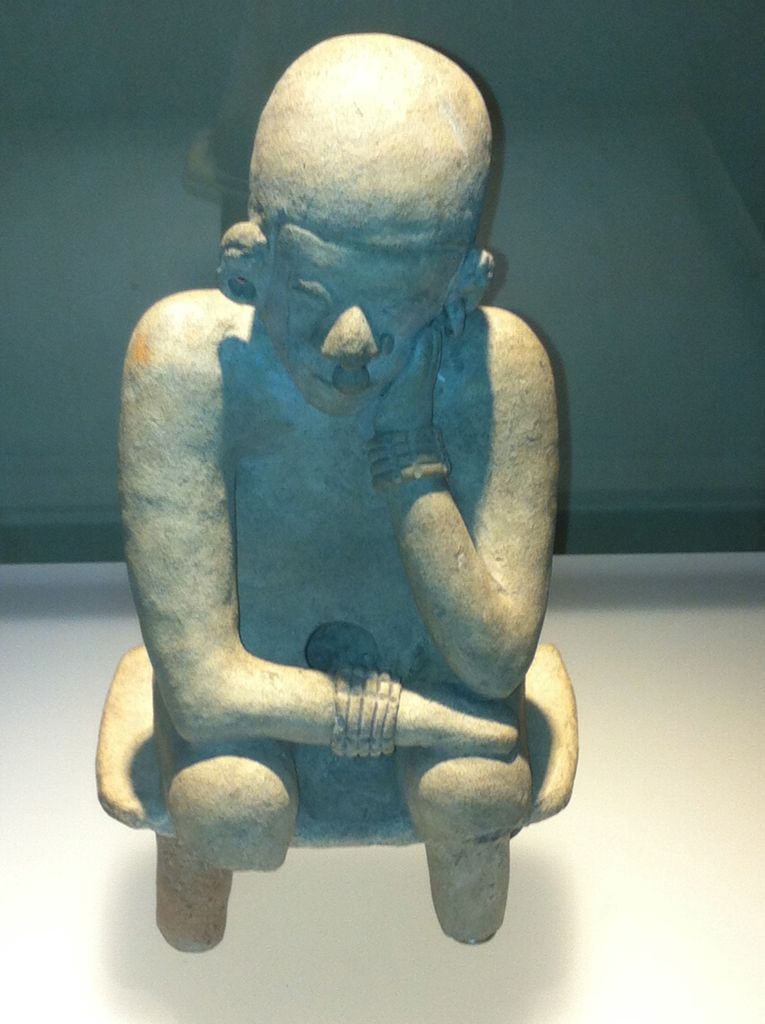

The figure below, a pre-Columbian anticipation of Rodin’s Thinker – the elongated head apparently indicates status, but could equally well be the result of ingesting too many of the aforementioned hallucinogens – was particularly striking.

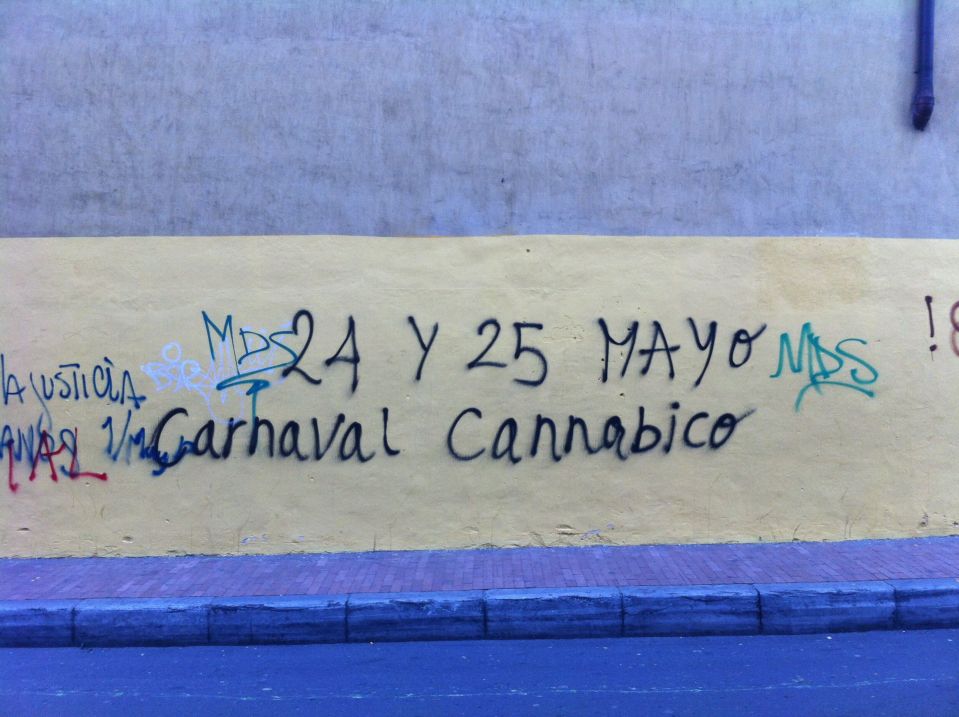

Finally, on a not unrelated theme, a nice piece of street graffiti from Bogotá advertising a ‘Carnaval Cannabico’, in which we might safely guess that very little got done.

The cities within yourself

This has been Turkish week, but also – and with a synchronicity that pleases me very much – Greek week. The London Book Fair had Turkey as its ‘Market Focus’ and two expeditionary groups of Turkish writers descended on the city of Cardiff (whose football team, it will be noted, are playing in the Premier League next season). Meanwhile, I have been immersed in the work of the Greek poet, C.P Cavafy, whose 150th anniversary we celebrate this year.

The first group of visitors were poets, three of whom I have been involved in translating. They are Gökçenur Ç, Efe Duyan, Adnan Özer and Gonca Özmen (the illustration above shows the cover of a booklet of their work, produced by Literature Across Frontiers, The Scottish Poetry Library and Delta Publishing). After an unforgettable lunch (which deserves a post of its own), the poets were joined by fellow-translator Zoë Skoulding and Literature Across Frontiers director Alexandra Büchler for an evening of poetry and conversation at Coffee a Gogo, just across from the national museum of Wales.

Then on Thursday, we were visited by the Turkish novelists Ayfer Tunç and Hakan Günday for a reading and discussion of their work, under the heading ‘Alone in a crowd’. The idea was to discuss the theme of cities – our citizenship, I guess – or experience as city dwellers. When preparing for my own contribution, I was immediately reminded of a line by one of the Turkish poets I hosted last weekend:

The more you travel the more cities you will find inside yourself

Which had led me to ask its author, Adnan Özer, how well he knew the work of Cavafy, a writer of whom I have been a fan, no, a devotee, since my mid-teens. Adnan told me that he admired Cavafy’s work, but that he was not a major influence, apart from in that particular poem.

The poem behind the poem, if you like, is this one:

THE CITY

You said: “I’ll go to another country, go to another shore,

find another city better than this one.

Whatever I try to do is fated to turn out wrong

and my heart lies buried as though it were something dead.

How long can I let my mind moulder in this place?

Wherever I turn, wherever I happen to look,

I see the black ruins of my life, here,

where I’ve spent so many years, wasted them, destroyed them totally.”

You won’t find a new country, won’t find another shore.

This city will always pursue you. You will walk

the same streets, grow old in the same neighborhoods,

will turn gray in these same houses.

You will always end up in this city. Don’t hope for things elsewhere:

there is no ship for you, there is no road.

As you’ve wasted your life here, in this small corner,

you’ve destroyed it everywhere else in the world.

(translated by Edmund Keeley and Philip Sherrard)

And it seems here, as in Adnan’s paraphrase, that the city is a cypher for the self, reflecting our fragmented or multiple selves. We know that Cavafy is speaking of his own beloved Alexandria, but we also know that the city here is a state of mind, one’s personal predicament – and the human predicament also – from which one can never shake free.

At the same time as being surrounded by a crowd, we are all ultimately alone (in the city, as elsewhere), despite the onslaught of synthetic familiarisation on offer from substitute communities such as Facebook and Twitter. On which theme, I was interested to read, in Russell Brand’s Guardian piece that he singles out one La Thatcher’s most devastating legacies in precisely this area. In the quest for personal advancement at all costs, in the elevation of blind greed as the most praiseworthy and rewarding of human qualities, we are almost duty bound to ignore the needs of those we share the world with. As her loathsome sidekick Norman Tebbit said, in reference to the defeat of the mineworkers’ union:“We didn’t just break the strike, we broke the spell.” The spell he was referring to (writes Brand) is the unseen bond that connects us all and prevents us from being subjugated by tyranny. The spell of community.

And if that all seems a bit random, Turkish week at LBF>Cardiff City Football Club>Turkish poets>Famous Greek Poet>living in the city>Thatcherism and its legacy – then please forgive me. It does connect, I promise. And if it doesn’t, well, like I said once before . . . blogging is a way of thinking out loud.

Tales of the Alhambra (or thereabouts)

Strange that in one’s memory a house takes on a different shape, a different context, becomes a dream house.

When I was living rough, a quarter of a century ago, I spent a couple of months in Granada. Along with some other homeless travellers we squatted a house on a sidestreet off Carerra del Darro, across from the Alhambra. It was a miserable building, known among those of us unfortunate to live there as ‘the house of a thousand turds’, for reasons that do not require too much explanation. But it provided some protection from the rain, and from the cold nights.

The point in this digression into my personal past is that I have often wondered about the house – or palace, as it became in my retrospective imagination: I have even wondered whether indeed it actually existed. I described its location in the vaguest of terms to Andrés, who has lived in Granada for over twenty years, and he could not think where such a palace might be. Surely it would be well-known, a palace on a hillside facing the Alhambra? It was bound, he said, to be somewhere on the Albaicín. He even mentioned consulting a local historian, who would be able to identify the mighty house from my description of it. I nodded assent, not really caring: the palace of my imagination would suffice.

It was just as well no one investigated my claim. I would have been heartily embarrassed. Last Wednesday, while walking up the hill from the Carrera del Darro (a river – actually a stream – celebrated in Lorca’s Baladilla de los tres ríos de Granada), I came face to face with a boarded-up building that immediately took me back through the years to 1988, and an appalling period of penury, sloth, craziness and some profound melancholy, living from hand to mouth – more often from bottle to mouth – through one Andalucian winter. I knew at once it was the building where I had slept. When I had stayed there, the building was already in a parlous state. It would seem that its role of providing a sleeping place for the homeless continued long after I had left the city. As one of my daughters pointed out however, the plans for restoration are well overdue. The sign apparently says the renovations are due for completion in the year 2008.

I stood back from the house and wondered at the capacity of the human brain to convert such a building into a palace. I find no answer. I have dreamed about the house, although it keeps shape-shifting. I have written about it, or versions of it. It is the opening setting for my short story ‘The Handless Maiden’, and provided the inspiration for a prose poem, which I reproduce below. But a palace it is not.

Dogshit Alley

It was my first and only visit to the artist’s apartment. He lived on the top floor. His studio offered a sensational view of the Alhambra. But first, he said, we had to negotiate dogshit alley. The artist spoke of it like one describing a secret shame. There was nothing he could do. On the third floor lived a resident who kept a wolfhound. She never exercised the dog, and let him use the landing as a toilet, which he did, prolifically. Formerly, the top flat had been empty, and no one came to visit the woman and her gawking beast. Now the artist was installed above her, and the woman had adopted the stance of long-term resident with rights. The dog, she said, harmed nobody. She seemed oblivious to the smell. The artist could not confront her. Each time he passed the landing he felt like vomiting. He tried speaking with the woman. She would stand in the doorway, the hound slavering and growling at her side. ‘Look’ she said, smiling meekly: ‘he wouldn’t hurt a fly. He’s an old softie’. She ruffled the grey fur on his head, and an incredibly long tongue flicked out and caressed the underside of her wrist. The woman smelled of gin, had white hair, parchment skin, and the smile of a ten year old. ‘He hates going out, see. He gets so scared’. The artist was lost for words. He told me: ‘I don’t know what to say to her’. When we climbed the stairs to the third floor the stench suddenly hit me. I held a handkerchief to my nose. We navigated the landing, stepping over mountainous turds. I didn’t breathe until we reached the attic studio, and walked out into the clean December air. The Alhambra stood magnificent against the backdrop of the Sierra Nevada: an impeccable statement that made me realise that it is the reproduction of a cliched image that renders a cliche, and not the original. ‘You see’, said the artist, ‘I just don’t know how to deal with her at all.’ He lived in the house of a thousand turds with a dying woman and an agoraphobic wolfhound for neighbours. This was the artist’s quandary and he could not resolve it.

(from Walking on Bones, Parthian, 2000)

Finally, on a trip to the coast, we have a modest lunch at Almuñecar, in the Manila bar-restaurant. On the way back to the car, we pass a vending machine, selling worms. That’s right: worms. Fisherman apparently puts money in the slot and a bag of live bait comes out. Who the hell thought this one up? These worms, they live inside the machine, possible for months on end. What do they do? What on earth can they do? What would you do, packed in plastic inside a vending machine? Have you ever heard of anything so extreme? Who would be a worm?

Finally, on a trip to the coast, we have a modest lunch at Almuñecar, in the Manila bar-restaurant. On the way back to the car, we pass a vending machine, selling worms. That’s right: worms. Fisherman apparently puts money in the slot and a bag of live bait comes out. Who the hell thought this one up? These worms, they live inside the machine, possible for months on end. What do they do? What on earth can they do? What would you do, packed in plastic inside a vending machine? Have you ever heard of anything so extreme? Who would be a worm?

The Accidental Tourist

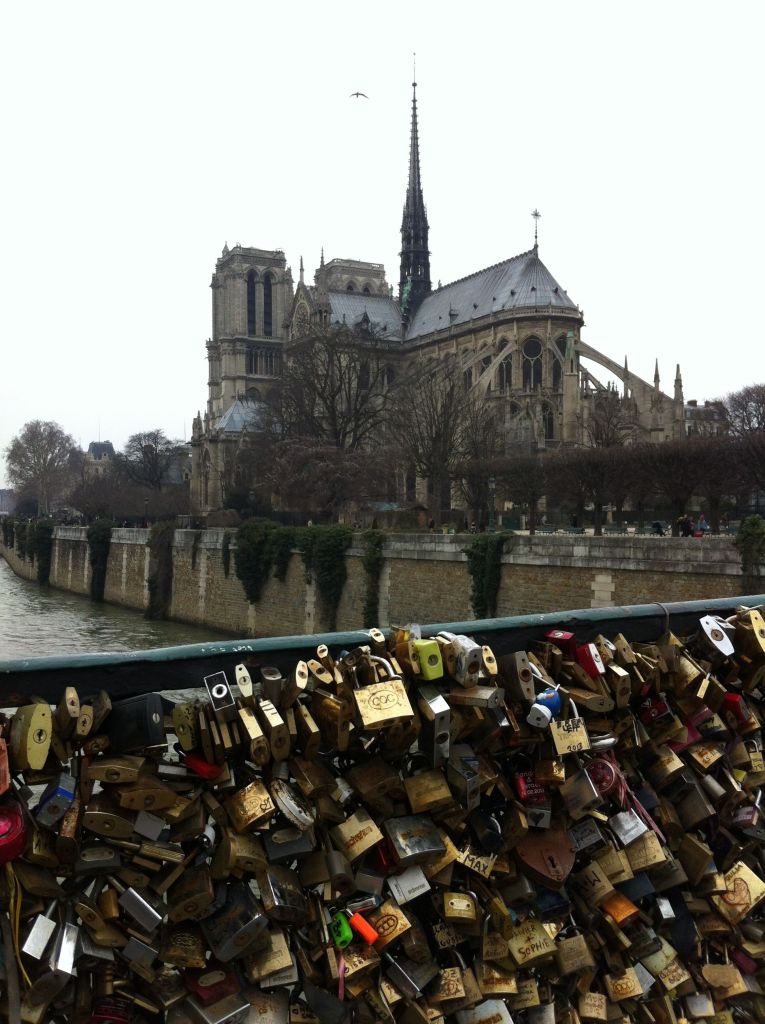

So I’m crossing a bridge, to get from A to B, and suddenly I’m on a film set. No, let’s correct that: I’m on a rolling series of film sets. This is what happens on a brisk stroll around central Paris. First, a polka through the old Jewish quarter, Le Marais, then across the river via the Pont des Arts (Le Fabuleux Destin d’Amélie Poulain, The Bourne Identity) as shown here in my artfully contrived photo, where lovers place padlocks, cadenas d’amour, in order to imprison the object of their desire for perpetuity. Then to lunch at Le Polidor, made famous by Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris.

I am pleased to report that our waitress lived up to my wildest expectations, embodying the French talent for what foreigners erroneously believe to be rudeness (a kind of exaggerated politeness, dressed with venom) which is actually something quite different: it is, as I discovered – and it took me years to work this out – a direct challenge to the interlocutor. It says: how are going to take this? Lying down like un wimp, or joining in with a bit of callous and vituperative banter of your own? If you opt for the latter, you cannot lose. If you succumb to the former – the classic anglo-american mistake – you inevitably feel maltreated and offended. So join in, dammit! Throw back a few witty and sophisticated remarks of your own, not forgetting to smile charmingly as you do so. It cannot fail.

Later in the afternoon, after strolling past the houses once occupied by Joyce (a British writer of Irish Origin?) and Hemingway (but also, and perhaps more significantly, Pound) what could be merrier than a crêpe, in a crêperie which my Argentinian companion, Jorge, assures me is the only place in Paris that serves dulce de leche – which I must admit I find hard to believe – in Rue Mouffetard.

Also recognizable from Amélie in Rue Mouffetard is the seafood stall at the bottom of that street, which nagged at my memory from I knew not where, but now I do.

It’s quite possible that a short walk around the fifth arrondissement satisfies the needs of all five senses more rapidly than anywhere else on earth. But who knows, perhaps I’m just biased.

The Losers’ Club

Following a comment made about my last post; namely Tom Gething’s remark that not getting it is essentially another way of getting it, I am reminded of the pragmatic consequences of not getting it, in relation to The Loser’s (sic) Club, an association of persons – I am not quite sure whether or not ‘membership’ is a valid descriptor here for one who has been randomly recruited – but you can read about it on Bill Herbert’s blog, Dubious Saints. The story concerns a very wet night in Istanbul in which Bill, Zoe and myself decided, at Bill’s insistence, that we find the place, the real place, rather than allowing it to remain where it clearly belongs, in the realm of the imagination. We even had a general direction, if not a precise map location. This urge to conjure the subliminal or the rumoured into actual existence is precisely the kind of ‘getting it’ that most handsomely illustrates Phillips’ thesis. Getting it, (in this instance, locating and identifying a place called The Loser’s Club) becomes a sort of insanity, and is most definitely to be avoided.

And yet . . . one can see the allure. The club – or rather our desire for it – beckoned us on under the persistent downpour, through street after street of not getting it.

You will notice that on the sign, (photo courtesy of Nia Davies, a ‘member’ of the club) that the apostrophe is placed before the s, indicating that there is only one loser in the loser’s club. This shatters all concepts of a club. A club of one is something of a paradox, if not simply a contradiction. It also means that if the eponymous loser is not at home, then no one will be there to open the door.

I must ask myself: did not getting it, I mean, not getting, or finding, the losers’ club (in his post Bill opts for a more felicitous use of the apostrophe) enhance or enrich my life? I don’t know, because I never got there. We went somewhere else instead, and that was OK, but you never know what you’ve missed when you don’t get it, you only know what you get, which isn’t what you originally sought, and therefore isn’t it.

On Not Getting It

Curiosity can sometimes be more satisfying, more enhancing, than the mere consolation of achievement.

A while ago I wrote here on Kafka’s claim that in spite of knowing how to swim, he had not forgotten what it feels like to not know how to swim – and consequently the achievement, or consolation of ‘being able to swim’ was only of any value when weighed against the state of curiosity and mystery of not knowing how to swim.

Or something like that.

Adam Phillips, in his excellent book Missing Out, says something very close to this. In the chapter ‘On Not Getting It’ he writes that sometimes ‘not getting it’ (whatever ‘it’ might be – knowing how to swim, or winning some straightforward or else obscure object of desire) is more interesting than ‘getting it’. He imagines a life ‘in which not getting it is the point and not the problem; in which the project is to learn how not to ride the bicycle, how not to understand the poem. Or to put it the other way round, this would be a life in which getting it – the will to get it, the ambition to get it – was the problem; in which wanting to be an accomplice didn’t take precedence over making up one’s mind.’

There is something very appealing about this notion of ‘not getting it.’ Here’s more:

‘What I want to promote here is the alternative or complementary consideration; that getting it, as a project or a supposed achievement, can itself sometimes be an avoidance; an avoidance, say, of our solitariness or our singularity or our unhostile interest and uninterest in other people. From this point of view, we are, in Wittgenstein’s bewitching term, ‘bewitched’ by getting it; and that means by a picture of ourselves as conspirators or accomplices or know-alls.’

For now, I am surprisingly happy to be bewitched by the notion of not getting it; to remain enhanced if occasionally bewildered by my inability or disinclination to get it.

The other side of the other

In my last post I mentioned that perennial companion and source of consternation, the other, the doppelganger, the one who walks beside us, both ourselves and not ourselves.

I cited the introduction from Orhan Pamuk’s memoir of Istanbul, but cut the quotation short. I did this on purpose, because Pamuk leads off into the dark side of the other, to the fear of replication that beset him when he once came to grips with the awfulness of one’s own doubling:

On winter evenings, walking through the streets of the city, I would gaze into other people’s houses through the pale orange light of home and dream of happy, peaceful families living comfortable lives. Then I would shudder, thinking that the other Orhan might be living in one of these houses. As I grew older, the ghost became a fantasy and the fantasy a recurrent nightmare. In some dreams I would greet this Orhan – always in another house – with shrieks of horror; in others the two of us would stare each other down in eerie, merciless silence.

‘As I grew older’. There’s the rub. Just as all literature leads us back to children’s stories, as Borges notes, so, in an inverse sense, stories that begin as childhood diversions, of daydreaming and harmless fantasy, with time become the stuff of nightmares. The prospect of possessing (or being in the possession of, possessed by) a double, a version of oneself both intimate and foreign, both known and unknowable, intrudes into consciousness with the stealth of a thief, come to steal our bones, come to steal our soul.

After reading my last post, The one who walks alongside us, a friend commented that in Freud’s essay ‘The Uncanny’, he refers to the terror implicit in the concept of the double, the creeping horror of replicating something long known to us, once very familiar, but which has now become terrifying. What could be more familiar to us – and therefore possess the greatest potential for horror – than ourselves?

In literature, notably in the works of Edgar Allen Poe, Guy de Maupassant, Alfred de Musset, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Joseph Conrad, Jorge Luis Borges and Thomas Bernhard, we frequently encounter something approaching a paranoid state revolving around the persecution of the ego by its double. Otto Rank, Freud’s precursor in the study of the double, compares these imaginary creations to their authors’ symptoms, through which the theme of the double reveals a psychopathological dimension. Well . . . you might see it that way, you might even, as Freud suggests, see the expression of the double as a symptom of the ego’s inability to outgrow the narcissistic phase of early childhood, but that would be to pathologize a great number of writers, and I don’t for one moment believe in the notion that you have to be mentally ill to be intrigued by the notion of a double, or to write effectively on this theme, or to be encouraged to think there may be some profound connection between an awareness of one’s own otherness (expressed in many ‘traditional’ cultures as an animistic belief in immortality) – or to believe that after a certain age it should be regarded as an unhealthy or pathological condition.

We all possess the ability to imagine ourselves as other, and this imagining, or daydreaming, is the beginning of all literature. How appropriate then, that when a writer sets out to put down an account of his or her own life, they seem best able to do this by imaging their story as one that happened to someone else. It seems to be the core paradox that confronts anyone who writes a memoir, and has certainly been my own experience.

Pamuk too, apparently: “I’d have liked to write my entire story this way – as if my life were something that happened to someone else, as if it were a dream in which I felt my voice fading and my will succumbing to enchantment.”

More to follow. Written either by me, or the other bloke.

The other who walks alongside us

On the radio this morning the Turkish writer Elif Shafak prepares me for a journey. I am listening to Istanbul, she says, and we share the sounds of the city, which dissolve, eventually into water. ‘Everything in Istanbul,’ she says, ‘is fluid.’ And there are two different kinds of fluidity, the elements of oil and water. It is a liquid city, a city that never stops becoming.

Istanbul’s fluidity, its sense of becoming, of becoming another, even at the same time as becoming itself, reminds me of the opening of another work by a contemporary Turkish writer. Orhan Pamuk begins his love poem to his home city: Istanbul: Memories and the City, as follows:

From a very young age, I suspected there was more to my world than I could see: somewhere in the streets of Istanbul, in a house resembling ours, there lived another Orhan so much like me that he could pass for my twin, even my double. I can’t remember where I got this idea or how it came to me. It must have emerged from a web of rumours, misunderstandings, illusions and fears . . . But the ghost of the other Orhan in another house somewhere in Istanbul never left me.

How many of us must share this notion of a double, breathing our air, thinking our thoughts, eating our food, dreaming our dreams; but also at a remove, always elsewhere, always and inevitably engaged in being someone other than ourselves.

How to write a novel

What to do when you are writing a book and one of your characters won’t behave, won’t toe the line, won’t stay on the page?

You go for a little lie down in the afternoon sun. Sleep a while. It’s 25 degrees centigrade in January, for heaven’s sake. You can always write later. On waking you will hear the murmur of a sea so placid, so translucent, that you can just make out the octopi telling jokes. (They spend most of their time telling jokes and playing eight handed cribbage).

Octopi (or octopuses) are gravely misunderstood creatures, as any watcher of nature programmes can attest. Here is a short video of a BBC diver getting snogged by a very big octopus.

How to remain creative when the shitstorm strikes

First of all I would like to wish a Happy New Year to all readers of Blanco’s Blog, albeit a day late. Secondly, I’d like to thank all of you for the more than 30,000 visits to the blog made during 2012.

Third of all, I was wondering today: How do people manage to be creative, when they are assailed on all sides by the mad onslaught of the day-to-day? The hurricanes of shit that come flying at us from all directions via our jobs, from a permanent state of information overload, from our family commitments, financial responsibilities, and from trying to cope with the humiliating nightmare of still having our lives run by the very bankers who stuffed us in the first place – all, in other words, of the aforementioned shitstorm, and still, still, to reserve some time of the day in which to carry out so-called creative work. I say so-called because I am of the belief that everything one does can be creative, but am here talking strictly about those of us who have a commitment to a specific artistic medium, be it writing, painting, sculpture, music, mosaic, dance or theatre, photography or whatever . . . even baking. But not banking. No. Banking might well involve creativity too, but it is all the wrong kind, most definitely.

One of the most difficult things for me personally, as a chronic re-drafter of my texts (though not of these posts, which I tend to write straight off, often perhaps to their literary or stylistic detriment) is to gauge exactly how much time I should spend on trying to resolve a problem. A video recording of a talk by John Cleese informs us that Donald MacKinnon, the psychologist and researcher into creativity, found that the most successful creative professionals always played with a problem for much longer than their less successful peers. They tolerated, put up with, the discomfort, the nervous tension and anxiety; all the stuff that we experience when we need to solve a creative problem under pressure. And most of us will take a decision earlier than necessary, not because it is the best one, but because it makes us feel better by having taken it. The most successful creative people tolerate the uncertainty much longer, even thrive in the uncertainty. They are able to defer decision-taking till the time it suits them (the eleventh hour, often) in order to give themselves maximum pondering time.

Maybe this is a bit like breaking through the pain barrier for athletes, but I wouldn’t really know.

Anyhow, I will stick the John Cleese video up here, in case others who are not familiar with his rather useful thoughts on this subject should care to watch.

Surely to goodness

‘Surely to goodness you will not my pub be taking from me’, cried Llewelyn to the foreign gentleman.

As an afterthought to yesterday’s post, I was distressed to hear the foot soldiers in Tietjens’ regiment, the Glamorganshires, speaking a hammy stage Welsh. Their speech abounded with arcane and weird phrases such as ‘surely to goodness’ – indeed one poor fellow could say little else. I have leafed through the Madox Ford novel but have not tracked down the offending passage: could it be Tom Stoppard’s intervention, or does this extraordinary language represent how a certain breed of English person thinks the Welsh peasantry actually speak? ‘Surely to goodness; indeed to goodness; a good man he is; on the table the tea is; it is his beer he’ll be wanting.’ Do these phrases actually exist outside the heads of English writers trying to “do Welsh”?

The problem of transcribing the language of people who are speaking a second language is a recurrent problem for the novelist. It is related to, though not the same as, attempts made at rendering the syntax and word order of another language, but transcribed as though they were speaking English: Hemingway provides some hilarious examples of this in The Sun Also Rises and For Whom the Bell Tolls, with Spanish. For example, opening a page of the latter book at random, we find:

“Fernando,” Pilar said quietly . . . “take this stew please in all formality and fill thy mouth with it and talk no more. We are in possession of thy opinion.”

I am sure we could open this into a fascinating discussion, but I merely intended, in the first instance, to make a note that it would be very weird, in 2012, to hear a ‘typical Welshman’ saying things like ‘Surely to goodness’. The truth is that never, but never, have I heard a Welsh person say any such thing. And while I can speak about the Welsh with some authority, I must also confess that I have never heard a Yorkshireman say ‘Ee bah gum’, or a Irishman say ‘Begorrah’, (although this does not necessarily mean that these things never get said and so leads us into speculation). Representations of the other always have to be accompanied by some linguistic marker of ‘foreignness’. Welsh is a VSO (Verb-Subject-Object) language but this does not appear to have filtered into the English transcription of first language Welsh speakers attempting to communicate in English.

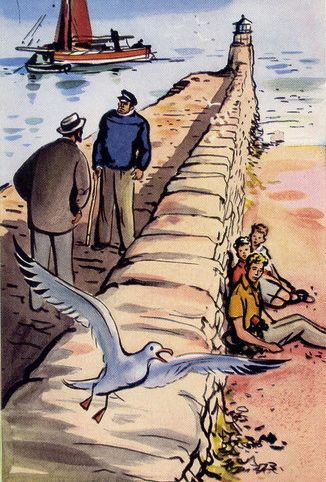

So, to return to Enid Blyton, and the seventeenth adventure of the Famous Five: Five get into a Fix. The kids go off to a place called Magga Glen and stay with a little grey haired old Welsh lady who speaks in the peculiar fashion I have described. She is, in many ways, a replica of another Mrs Jones (all Welsh people are called Jones, after all, and all their children run around barefoot, dressed in rags, stealing cheese). This other Mrs Jones runs the Inn in The Ragamuffin Mystery, another, lesser-known Welsh-set adventure by Blyton. There is an evil ornithologist (ornithologist was Blyton’s favourite long word, and she manages to get it into her stories with improbable frequency), and the lady of the Inn makes pronouncements such as: “He’s not bad is my Llewellyn, not wicked at all. It was those men, with their lies and their promises. They tempted my poor Llewellyn, they lent him money to buy the inn.” Note: in Blyton adventures ‘bad men’ are of two varieties: members of the ‘lower class’ and ‘foreigners’ (of indeterminate breed, but invariably unshaven and speaking ‘with an accent’).

And there’s the moral. Never borrow money from bad men, especially foreigner bad men, in order to buy a pub. Surely to goodness no.