Knowing how not to swim

I have just picked up (and put down) a fat novel by a leading British novelist. It doesn’t matter which one. It was shortlisted for the Man Booker a few years ago. It’s meant to be a cracker. But I can’t be bothered to read it. I know it’s supposed to be oh so very good and all that: ‘well-written’, ‘unputdownable’; ‘a masterpiece’ even, but can I be arsed to invest the amount of time needed to complete it, when essentially, I know what is going to happen from Page One, and also how it will be told, by glancing over the first few pages? Probably not.

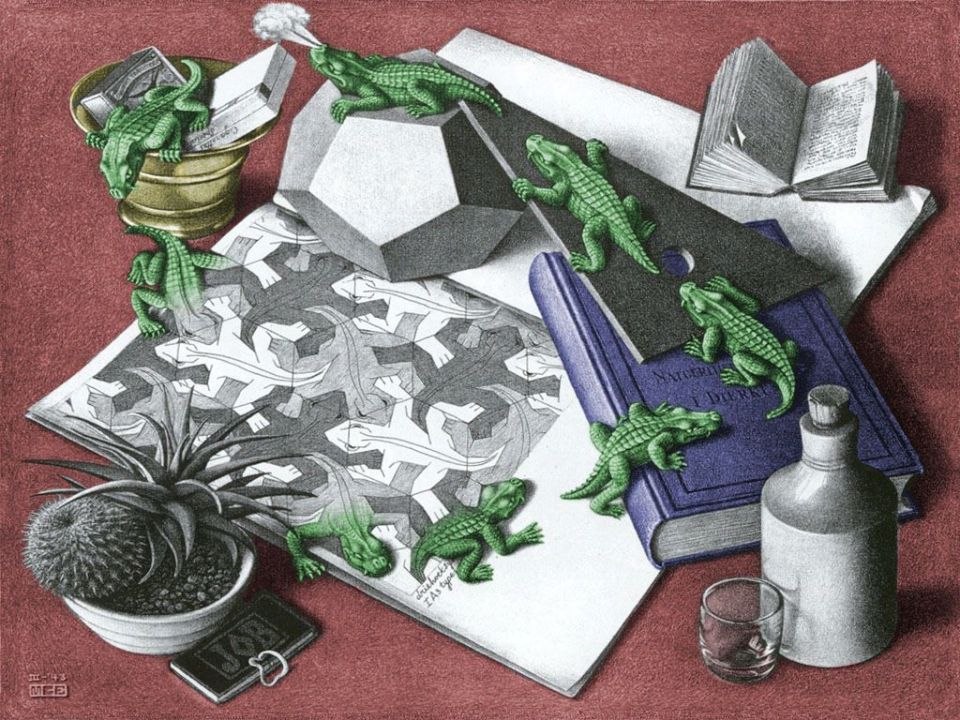

There are two ways of looking at the world, and they lie behind two ways of doing literature. The first way, to quote Roberto Bolaño, consists of stories that are “easy to understand”. They imply a linear narrative, a degree of suspense, a beginning, a middle and an end – preferably in that order. As Bolaño wrote, these books “sell and are popular with the readers because their stories can be understood. I mean” – he goes on to say – “because the readers, as consumers . . . understand perfectly (these writers’) novels or their stories.”

Which brings me to an article I read over the summer in a newspaper by the novelist Enrique Vila-Matas. For those who read Spanish, it’s available here.

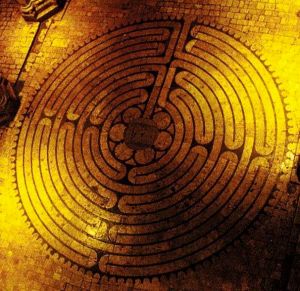

There are two groups of people, writes Vila-Matas – more or less, as I am paraphrasing. One lot insists that things are the way they are, that life is simply thus, and it’s not worth worrying your socks off about it. The other group, of whom V-M is perhaps a particular offender, believe that they don’t quite belong on this planet, that they are restlessly in pursuit of another place, which might be called death, but quite possibly has some other definition entirely . . . V-M likens the distinction between these two types of person to those whose literary predilections lie in the direction of a simple story, well told – the kind disparaged by Bolaño – and those others who are enthralled “by complexity and by the labyrinth”, and who will always find ways of constructing stories in a different and more complex manner, and will always try to see more. (In ordinary life, this latter group are often compulsive liars, or fantasists, or are confined to institutions of one kind or another.)

Put another way, in the lounges of those conservative writers who adhere to some kiss-and-tell narrative linearity based on the novels (and to an extent, the ideology) of the nineteenth century, the world is described as ‘given’. Whereas in the slums and squats occupied by these more complicated types, a kind of negativity is evoked which, suggests V-M, might find an allegory in this quotation from Kafka:

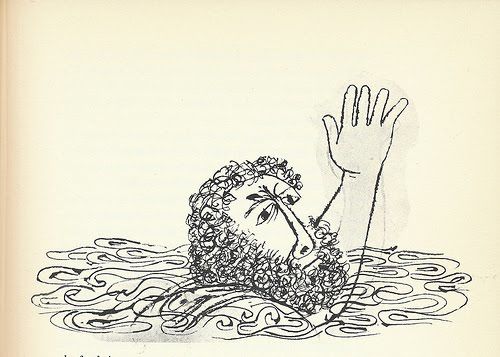

I know how to swim like the others, but I have a better memory than they do and I have not forgotten my old inability to swim. And as I have not forgotten it, the ‘knowing how to swim’ part isn’t of much use to me, and so, in consequence, I don’t know how to swim.

Perhaps then, some of us, although we have learned to swim, sometimes practise drowning, just to remember what it feels like.

So it is, too, that some writers, even though they know how to write in a certain linear way, to write a certain kind of story, that ‘can be understood’, elect not to, and opt instead for the labyrinth, or head for the deep forest. Perhaps they find it more of a challenge that way, more fun.

Writing in bed

I suppose it’s inevitable that we return to the same themes again and again in the course of a writing career, particularly – as is inevitably the case – the same damn things keep cropping up.

Take illness, for example. From an early age, I linked illness with storytelling. My father was a GP, my mother had been a nurse throughout World War Two, both in London during the Blitz and in what was then called ‘The East’. I grew up listening to medical stories. In the village I would hear people talking about their illnesses. Sometimes I would hear their views (when they didn’t notice I was there) on my father, of what a fine gentleman and doctor he undoubtedly was, but of how they ‘wished sometimes he would take a firmer hand with people and tell them what was what’. I, as his son, had evolved a somewhat contrary impression, but that, of course, is to be expected.

Walter Benjamin speculates somewhere about the possible relationship that exists between the art of storytelling and the healing of illness. I know what he means, and have been circling around it, on and off, all my life, much of the second half of which, thus far, I have spend as a chronic, or recidivist patient.

Many, or most of my favourite writers, have been consistently and wretchedly ill, or bed-ridden, or rather, have spent long tracts of time in bed. Coleridge, De Quincey, Stevenson, Proust . . . I am well aware that, like myself, this list (which could be greatly extended) includes those who are termed to have ‘self-inflicted’ illnesses brought on by their vices or addictions. But until last week I had never read Virginia Woolf’s wonderful little essay ‘On Being Ill’. If indeed it can be called an essay, rather than a series of digressions on a theme. I found a very attractive edition, published on nice paper, by The Paris Press in 2002, with an Introduction by Hermione Lee, which I can recommend.

The essay was first published by TS Eliot in his New Criterion magazine in January 1926, despite his unenthusiastic response to it. The essay was, we learn from Woolf’s later correspondence, written in bed, never a bad place to write, I find personally. But Woolf was concerned: “I was afraid that, writing in bed, and forced to write quickly by the inexorable Tom Eliot I had used too many words.”

The essay was first published by TS Eliot in his New Criterion magazine in January 1926, despite his unenthusiastic response to it. The essay was, we learn from Woolf’s later correspondence, written in bed, never a bad place to write, I find personally. But Woolf was concerned: “I was afraid that, writing in bed, and forced to write quickly by the inexorable Tom Eliot I had used too many words.”

“Writing in bed” continues Hermione Lee in her Intro, “has produced an idiosyncratic, prolix, recumbent literature – the opposite of “inexorable” – at once romantic and modern, with a point of view derived from gazing up at the clouds and looking sideways on to the world” – and here I am reminded of E.M. Forster’s memory of Cavafy, as of a man ‘standing [or lying] absolutely motionless, at a slight angle to the universe.’ “Illness and writing are netted together from the very start of the essay.”

But is writing in bed for everyone? How about novelists, the novelists of Big Books? Can you imagine Balzac, for instance, writing in bed? Certainly not: he would rather be charging apoplectic up and down the drawing room, tearing down the curtains and writhing on the floor chewing the carpet.

No, Virginia, has strong views on the ill-wisdom of composing entire novels in bed:

“Indeed it is to the poets that we turn. Illness makes us disinclined for the long campaigns that prose extracts. We cannot command all our faculties and keep our reason and our judgment and our memory at attention while chapter swings on top of chapter, and, as one settles into place, we must be on the watch for the coming of the next, until the whole structure – arches, towers, and battlements – stands firm on its foundation.”

Monsieur Proust, however, might have been inclined to disagree.

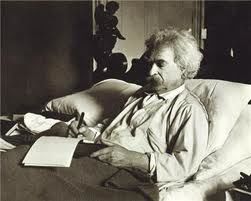

If you google ‘writing in bed’ a surprising number of articles appear, including one from a blog by Chris Bell (from whom I borrowed the image of Mark Twain) and by Robert McCrum, about whom I have many reservations, but am open-minded enough to leave this link.

Good things about being Welsh: No. 6 – beating Germany at football, meeting Ian Rush (and becoming a father).

Ian Rush and Blanco

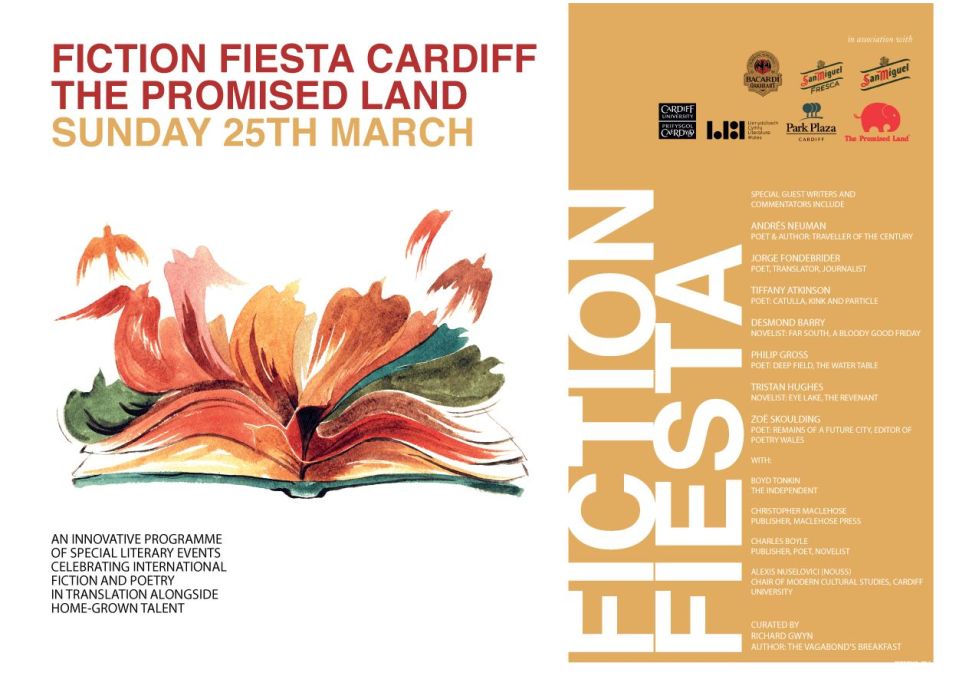

Blanco, not renowned as a great footballing fan, more of a rugby man, must confess to having had a little thrill last night meeting and having a drink with Ian Rush, Liverpool and Wales footballing legend. We were introduced by mutual friend, owner of The Promised Land and general good chap Nick Davidson at the Park Plaza Hotel in Cardiff. (Rushy’s hand is actually on my left shoulder, which means we are kind of mates, no?)

Among his many achievements, Rushy scored the winner in Wales’ 1991 defeat of reigning World Champions Germany in a European Championship qualifying match played at Cardiff Arms Park on the evening of 5 June, the only occasion, as far as I know, on which Wales have beaten Germany at anything. I happen to remember the date particularly well as it was the night our first child, Sioned Maria, was born. In fact – as I let Mr Rush know last night – it was because of his goal that the obstetrician was late arriving on the ward, coming into the room in which Mrs Blanco was at the closing stages of a difficult 10-hour labour. The doctor burst in proclaiming ‘Rush has scored’. ‘What’s he on about? mumbled Mrs Blanco, in a slightly medicated drawl, ‘and who the hell is Rush?’ Well, his spectacular goal, shown below, provides the answer to that one.

We won, Sioned was borned (yes, borned) and Cardiff went bonkers. Dazed, I wandered into the hospital car park at 2.00 a.m. and could not remember where I’d put the car. A security guard approached me, and when I said I couldn’t remember where the car was, for some reason assumed I was inebriated, and asked whether I was sure I should be driving. I wasn’t drunk, but driving through the city centre – very carefully, due to the inconsiderate presence of so many citizens – to get back home, most of the rest of the city was in a state of great exuberance. Truly, amigos, a night to remember, and one to bore the grandchildren with when I start repeating myself incessantly. When I start repeating myself, incessantly.

The many uses of freedom

Listening to Zadie Smith on the radio the last week I discovered the existence of an app called Freedom, which enables one to disconnect from the internet for a set period, say, two hours, and to write, without (in my case) trundling down, and then up, two flights of stairs to disconnect the modem or router, thereby pissing off anyone else in the house who wants to use the internet.

But how interesting that the app Freedom should be so called, when the internet prides itself on, and became the phenomenon that it is, by providing the ‘freedom’ to travel in cyberpace, that is, the freedom to access, within a split second, information on a scale and of a variety never before imaginable.

How interesting that now ‘freedom’ can also be sold, for ten dollars, as the ability to evade that other, all-engrossing, all-pervasive freedom, the one that takes away our own integral freedom to sit in solitude and write.

But it works. Simply knowing that I cannot access the internet on my laptop paradoxically saves me from having to wonder whether or not to consult it; saves me, in those lacunae of imaginative activity, from checking to see whether anyone has sent me a crucial email – one that clearly cannot wait 120 minutes to answer (120 minutes is my preferred setting: any longer and I might be tempted to dawdle, any less and I won’t get enough done. I have also calculated that when I am focused, I can manage just over 1000 words in two hours, and that is enough for first-draft fiction-writing. Much more and I am in danger of overstretching my resources and will have less in the tank for the next day).

So, thanks for the tip, Zadie. It really works. Of course, I could just throw out the computer, and write with pen and paper. But I fear it’s too late for that. So utterly have I been enslaved by writing directly onto a keyboard that it is only with difficulty that I can read my own handwriting.

The Arabian Nights and Franz Kafka

I would hate to give the impression that I do not enjoy reading novels. It is just that in the normal course of my work I read an awful lot of fiction and sometimes I like to take a break, and prefer to read other things. Last month, for instance – and this is not unusual – I read a good deal of poetry, and especially enjoyed re-acquainting myself with the wonder that is Federico García Lorca.

Also, as some followers of this blog might recall, I entered the weird realm of Stranger Magic, Marina Warner’s absorbing study, subtitled ‘Charmed States and the Arabian Nights’. The many handwritten footnotes, exclamation marks and marginalia in my copy will no doubt draw me back to the book over and again during the years ahead. Borges comes up for special attention in Ms Warner’s book, not least for his essay ‘The Translators of The Thousand and One Nights’, in which he argues, according to Warner, that “every reader can be, and should be, creative; that you can make up the stories as you please. In the process, the translator is being translated.” What a wonderfully liberating notion! One of those ideas that makes you realise that yes, that is how reading goes, when it is going at its best, which is what makes it more of a pleasure than writing (a view, incidentally, expressed by Zadie Smith on a Radio Four interview yesterday afternoon, causing me to nod my head sagely while juicing a vile concoction of raw beetroot and spinach).

But it is the huge scope and influence of the stories that Shahrazad (or Scheherazade) weaves for the murderous Sultan to stave off her own (and her sister Dunyazad’s) execution that most preoccupy Marina Warner; that and the labyrinthine cultural mythologies that attach to tales with which almost everyone feels familiar, either – at the posh end of the market – through the exhaustive and archaic translation of the Victorian explorer, swordsman, linguist and pornographer Sir Richard Burton, or else, more likely, via the mock-heroic exertions of Aladdin, either in the town hall pantomime or Walt Disney Productions. Take your pick. Personally I would dearly love to own a leather-bound first edition set of Burton’s Nights.

What most interests me, however, are the ways in which, at a profound level, the feats described in The Thousand and One Nights – all those jinns (or genies) and magic carpets and animal transmutations – together create a pervasive magical sensibility that has cast its influence on many aspects of world literature, from early science fiction, through Victorian Gothic fantasy to Latin American and eastern European so-called magic realism. Warner also spends some time with Kafka, claiming that his:

“style, its careful accountancy of detail and its measured verisimilitude, performs a sleight-of-hand to obscure the symbolic, allegorical and fairytale character of his tales. Gregor’s metamorphosis is presented as an event that has taken place, and it involves a complete hypostatic change: species and substance into the real presence of a monstrous bug. No agents of the change are invoked, unlike the mythological tales by Ovid which Kafka echoes in the his story’s title, or the jinn who change men into beasts in the Nights, because this new, modernist supernatural does not presuppose a hierarchy of beings, higher and lower, divine or diabolical: the daimon occupies a here and now, curled up in the word that brings the thing – the bug – into being on the page for us, the readers.”

Although four stories by Franz Kafka are referenced in Stranger Magic, one that seems to have slipped through Warner’s fastidious net is ‘The Bucket Rider’, a short piece written when Kafka had escaped Prague, to spend a terrible, freezing winter in Berlin with Dora Diamant. The story begins:

Coal all spent; the bucket empty; the shovel useless; the stove breathing our cold; the room freezing; the trees outside the window rigid, covered with rime; the sky a silver shield against anyone who looks for help from it. I must have coal; I cannot freeze to death; behind me is the pitiless stove, before me the pitiless sky, so I must ride out between them and on my journey seek aid from the coal dealer . . .

. . . My mode of arrival must decide the matter; so I ride off on the [coal] bucket. Seated on the bucket, my hands on the handle, the simplest kind of bridle, I propel myself with difficulty down the stairs, but once downstairs my bucket ascends, superbly, superbly; camels humbly squatting on the ground do not rise with more dignity, shaking themselves under the sticks of their drivers . . .

Needless to say, the story ends badly, with the coal dealer and his wicked wife refusing to give even a shovelful of coal on credit, and the bucket-rider flying off into oblivion: “And with that I ascend into the regions of the ice mountains and am lost forever.”

I mention the story only in passing, having been reminded of it in this week’s TLS, in an article about Kafka by Gabriel Josipovici, titled ‘It must end in the inexplicable’ (TLS, 7 September 2012). The main point of the reference in the article is to dismantle an interpretation of the story by another critic, June Leavitt. But for me the central trope of the story is sufficient to link it to The Thousand and One Nights, whatever the interpretative differences we may entertain about Kafka’s intentions – which in any case is not a discussion that much interests me.

How else, we may wonder – other than through the universalism of the Arabian Nights stories – did the damned camels get into a story set in the icy Berlin winter?

The chattering mind

The modern novel obsesses about itself. For many writers of novels, and of short stories, the act of narration itself becomes the topic of storytelling. I was culpable of this myself in my first foray into novel-writing, The Colour of a Dog Running Away, which is (and which always set out to be) a study in the art of storytelling, and in which the nature of the story being told is itself always and forever under scrutiny. I was, in those days – and in many ways remain – a disciple of Italo Calvino in this respect.

But how much of this reflexivity can we all take? I am currently reading Marina Warner’s ‘Stranger Magic: Charmed States and The Arabian Nights’ and am again struck, as I was in my childhood, by the sheer joy of storytelling in these archetypal and magical tales. I am reminded of Borges’ comment that all great literature becomes children’s literature, about which Warner comments: “he was thinking of The Odyssey, Don Quixote, Gulliver’s Travels and Robinson Crusoe as well as Tales of A Thousand and One Nights, but his paradox depends on the deep universal pleasures of storytelling for young and old: stories like those in the Arabian Nights place the audience in the position of a child, at the mercy of the future, of life and its plots, just as the protagonists of the Nights are subject to unknown fates, both terrible and marvellous.”

How far, then, is this mode of ‘simple’ storytelling from the convoluted twistings of what Tim Parks, in a recent article in The New York Review of Books, calls ‘the chattering mind’. Parks identifies this state of terminal parodic self-observation as the status quo of contemporary literary fiction (and presumably includes himself as an exemplar within this category). ‘Mental chatter’ (which several critics appeared to dislike about my Dog) can be seen as the single defining characteristic of this mindset:

Butor, Sarraute, Robbe-Grillet, Thomas Bernhard, Phillip Roth, Updike, David Foster Wallace, James Kelman, Alison Kennedy, Will Self, Sandro Veronesi, and scores upon scores of others all find new ways of exasperating and savouring this mental chatter: minds crawling through mud in the dark, minds trapped in lattices of light and shade, minds dividing into many voices, minds talking to themselves in second person, minds enthralled in sexual obsession, minds inflaming themselves with every kind of intoxicant, minds searching for oblivion, but not finding it, fearing they may not find it even in death.

Perhaps the challenge for novelists now is to find simplicity without being simplistic, to tap into the root of an intuitively convincing, spellbinding narrative that engages the reader at different levels (but without seeming pretentious on this score) and which, while allowing the chattering mind its share of the spoils, does not allow this bullying King Baby total dominance of the reading experience.

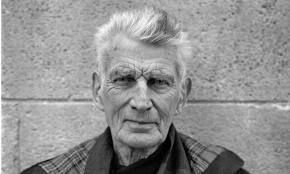

Otherwise we keep treading the endless spiral explored by Beckett, curator of the chattering mind school of literature, which, absorbing as it is, leads only to where one began, in endless repetition.

I realize now, in my middle fifties, what a huge, and in many ways, destructive influence Beckett wielded on so many of us growing up in the Godot generation (it was first performed three years before I was born); as much, say, as the influence that Joyce held over Beckett, and which he spent so long attempting to shed.

Tim Parks again:

Beckett exposes the spiral whereby the more the mind circles around its impasse, taking pride in its resources of observation, so the deeper the impasse becomes, the sharper the pain, the greater the need to find a shred of self-respect in the ability at least to describe one’s downfall. And so on. But understanding the trap, and the perversity of the consolation that confirms the trap, doesn’t mean you’ve found a way out of it; to have seen through literary consolation is just another source of consolation: at least I’ve understood and brilliantly dramatized the futility of my brilliant exploration of my utter impotence.

I will, however – no, therefore – continue in my quest to find the hidden passageways that connect A Thousand and One Nights with Endgame.

Rommel’s tailor and my father

If ever you are trapped in a hotel or hospital room and feel too ill-disposed or lethargic to read or write or engage in profound conversation with visitors (if anyone is foolish enough to visit you), you may wish to tune into one of several channels available to TV viewers that dish up potted histories of the twentieth century and are aimed, no doubt, at pensioners, or those of us who are infirm or bedridden or terminally idle, and who grew up in the shadow, even the distant shadow, of World War Two. Given that the Brits in general are morbidly obsessed with their performance in said war (I don’t think the Russians, for example, are so confused about their actual contribution), and given that it was the last occasion in which the citizens of these islands ‘pulled together’ as my mother was fond of reminding us, I personally have no difficulty in enduring hour upon hour of such documentary, especially those that delve deeply within the dark underworld of the Nazi party and its extraordinarily mediocre and sinister leadership. Perhaps this paradox is what most intrigues us. A favourite topic of these programmes seems to be ‘the plot to assassinate Hitler’, and the various theories about the involvement in such activities of the Desert Fox, General Erwin Rommel, who was ‘urged’ to commit suicide by Adolf Hitler, in order to avoid the negative publicity that would doubtless have redounded on the leadership if it were known that a war hero of Rommel’s stature were involved in the assassination attempt.

The other day, watching a programme about German POWs in England at the end of the war, I was reminded of an anecdote of my father’s. He was, for a while, medical officer at the POW camp based in Dover Castle. One morning, during surgery, a German soldier asked, through the interpreter, whether my father thought the state of his uniform befitted an officer of His Britannic Majesty’s Forces. My father, for whom sartorial matters were never of paramount importance, was rather taken aback by the audacity of the question, and asked the soldier why he thought it appropriate to comment on his state of dress. The soldier replied that he was simply trying to be of service, that he had served as personal tailor to Field Marshal Rommel, and was willing to make the Herr Doktor the most presentable officer in the British army, for the price of only two packs of cigarettes. My father, who didn’t smoke, reckoned this was a good deal, and handed over his uniform to the man, who duly returned it, immaculately re-tailored. He was so pleased with the result that he remained, for the duration of his stay at Dover, in the care of Rommel’s tailor for all matters of couture.

Eternal Return

What, if some day or night a demon were to steal after you into your loneliest loneliness and say to you: ‘This life as you now live it and have lived it, you will have to live once more and innumerable times more’ … Would you not throw yourself down and gnash your teeth and curse the demon who spoke thus? Or have you once experienced a tremendous moment when you would have answered him: ‘You are a god and never have I heard anything more divine.’

Nietzsche, The Gay Science.

What is it about Nietzsche and his infatuation with eternal return, an infatuation I seem to have acquired also?

I began this blog last July, having written myself into a hole with the novel I was working on. Writing the blog occupied the space I had dedicated to the writing of the novel, but with very different results. Thus it was that Blanco’s blog began as a displacement behaviour and quickly developed into a daily ritual. During the first few months I kept up a good pace, posting most days, and then in the new year the number of posts began to decline, although, reassuringly, the number of visitors did not drop in any substantial way.

Now almost a year has passed and I need to return to the novel that I abandoned when I started blogging. It is a case of the eternal return. Not a simple case (these things are never that simple), but definitely we have been here before. I need to pick up my tools and begin again the task I left off, as in a fairy tale.

Not that I intend breaking off from the blog altogether: no, I will continue to post, but perhaps at a less frenetic pace than when I first started out.

The blog goes on, and like everything else in nature, returns again and again to its starting place. Like Ariadne leaving her thread in the Cretan adventure, I follow the trail to the exit, finding only a sign that says ‘EXIT TO THE LABYRINTH’ (which is also the entrance to the labyrinth). The novel, the blog, the story, the labyrinth: it is all the same thing, and we keep returning here. If you wish to keep reading Blanco’s blog, you will find that this is all true.

The ‘very special place of love’: Roberto Bolaño, V.S. Naipaul, and sodomy.

A new addition to the mass of Bolaño miscellanea being published in English appears on the New York Review of Books blog. In an entertaining essay, Scholars of Sodom, Bolaño takes a delightful swipe at V.S. Naipaul’s absurd and arrogant attack on Argentina, in which the choleric Trinidadian decided that Argentina’s woes, political and cultural, stem from a typically macho predilection for buggery.

Luckily, the NYRB blog allows the reader to link to Naipaul’s original essay, Argentina: The Brothels Behind the Graveyard, as well as two others; The Corpse at the Iron Gate and Comprehending Borges. Best to focus on the first of these, as this is where he first lays down his extraordinary theory. Naipaul starts from the premise that Argentina is a land founded on the principle of plunder – of the Indians, of the land itself – a theme which he establishes early on and which he develops, after a tortuous route, towards a startling conclusion. Considering the macho attitudes that dominate Argentinian society at the time of writing (the essay was published in 1974), and the prevalence of bordellos, Naipaul warns that “Every schoolgirl knows the brothels; from an early age she understands that she might have to go there one day to find love, among the colored lights and mirrors.” And then, his coup de grace:

The act of straight sex, easily bought, is of no great moment to the macho. His conquest of a woman is complete only when he has buggered her. This is what the woman has it in her power to deny; this is what the brothel game is about, the passionless Latin adventure that begins with talk of amor. La tuve en el culo, I’ve had her in the arse: this is how the macho reports victory to his circle, or dismisses a desertion. Contemporary sexologists give a general dispensation to buggery. But the buggering of women is of special significance in Argentina and other Latin American countries. The Church considers it a heavy sin, and prostitutes hold it in horror. By imposing on her what prostitutes reject, and what he knows to be a kind of sexual black mass, the Argentine macho, in the main of Spanish or Italian peasant ancestry, consciously dishonors his victim. So diminished men, turning to machismo, diminish themselves further, replacing even sex by a parody.

Armed with this knowledge, Naipaul feels he has finally understood the Argentinians, with “their violence, their peasant cruelty, their belief in magic, and their fascination with death, celebrated every day in the newspapers with pictures of murdered people, often guerrilla victims, lying in their coffins.”

No holds barred here then. As Bolaño put it, in his imaginative response to the article, “Naipaul’s vision of Argentina could hardly have been less flattering. As the days went by, he came to find not only the city [Buenos Aires] but the country as a whole insufferably aggravating. His uneasy feeling about the place seemed to be intensified by every visit, every new acquaintance he made.”

Bolaño takes up the thread of Naipaul’s argument, and extemporises on the theme:

I remember, he writes, that when I read the paragraph in which Naipaul explains what he takes to be the origin of the Argentinean habit of sodomy, I was somewhat taken aback. As well as being logically flawed, the explanation has no basis in historical or social facts. What did Naipaul know about the sexual customs of Spanish and Italian rural laborers from 1850 to 1925? Maybe, while touring the bars on Corrientes late one night, he heard a sportswriter recounting the sexual exploits of his grandfather or great-grandfather, who, when night fell over Sicily or Asturias, used to go fuck the sheep. Maybe. In my story, Naipaul closes his eyes and imagines a Mediterranean shepherd boy fucking a sheep or a goat. Then the shepherd boy caresses the goat and falls asleep. The shepherd boy dreams in the moonlight: he sees himself many years later, many pounds heavier, many inches taller, in possession of a large mustache, married, with numerous children, the boys working on the farm, tending the flock that has multiplied (or dwindled), the girls busy in the house or the garden, subjected to his molestations or to those of their brothers, and finally his wife, queen and slave, sodomized nightly, taken up the ass—a picturesque vignette that owes more to the erotico-bucolic desires of a nineteenth-century French pornographer than to harsh reality, which has the face of a castrated dog. I’m not saying that the good peasant couples of Sicily and Valencia never practiced sodomy, but surely not with the regularity of a custom destined to flourish beyond the seas.

The danger in theorising outward from a single sexual act (one which seems to fill Naipaul with unspeakable horror) is that it creates a rather lopsided (and ultimately hilarious) simplification of Argentinian culture. It is a long time since I read Naipaul, and reading this quite demented essay, and Bolaño’s intelligent and witty response to it, reminded me why.

How interesting then, to read Ian Buruma’s review of Naipaul’s authorized biography (by Patrick French), also available on the NYRB website, and to discover that – when not beating her up – sodomising his Anglo-Argentinian mistress was Naipaul’s preferred occupation of an evening, while the cockatoos sang and the sun went down. Here is the passage summarizing their longstanding relationship, and the very special role of sodomy within it:

In Buenos Aires, at the apartment of Borges’s translator, Naipaul met Margaret Murray, a vivacious Anglo-Argentinian:

I wished to possess her as soon as I saw her…. I loved her eyes. I loved her mouth. I loved everything about her and I have never stopped loving her, actually. What a panic it was for me to win her because I had no seducing talent at all. And somehow the need was so great that I did do it.

Margaret left her husband and children, and for the next twenty years would be at the beck and call of her master, who was finally able to do all the things that had horrified and fascinated him before . . .The more Naipaul abused Margaret, the more she came back for more. She wrote him letters, paraphrased by French, about worshiping at the shrine of the master’s penis, about “Vido” as a horrible black man with hideous powers over her. Her letters were often left unopened, and certainly unanswered, adding to her sense of submission. According to Naipaul, he beat her so severely on one occasion that his hand hurt, and her face was so badly disfigured that she couldn’t appear in public (the hurt hand seems to have been of greater concern). But Naipaul said, “She didn’t mind at all. She thought of it in terms of my passion for her.” And then there was the mutual passion for anal sex, or as Margaret put it (paraphrased by French), “visiting the very special place of love.”

Funny the way things come round.

Beckett, Ritsos and stones

I am reading James Knowlson’s Damned to Fame: A Life of Samuel Beckett, which seems to be everything a literary biography should aspire to, and discover two passages that demand to be shared; the first of these is young Sam’s love of stones, which he would collect from the beach and bring home “in order to protect them from the wearing away of the waves or the vagaries of the weather. He would lay them gently into the branches of trees in the garden to keep them safe from harm. Later in life he came to rationalise this concern as the manifestation of an early fascination with the mineral, with things dying and decaying, with petrification. He linked this interest with Sigmund Freud’s view that human beings have a prebirth nostalgia to return to the mineral state.”

But never find Papa Sigmund, I am immediately reminded of the Greek poet Yannis Ritsos’ fascination with stones. Ritsos, who spent many years as a political prisoner, collected and painted stones throughout his life. According to a recent exhibition at the Museum of Cycladic Art:

The poet’s pictorial approach is evident in his solitary preoccupation with the natural contours of objects, such as roots, bones, and above all stones and pebbles, which are found in abundance in the arid islands of Greece, perhaps as a result of the universal “urge of expression against decay and loneliness”. Stones and pebbles: these were the materials that Yannis Ritsos used, the “plentiful raw material on which one could mark or underline by felt tip pen or Indian ink what the stone itself dictated”.

On the stones of Yannis Ritsos are depicted solitary figures or large groups of people, frontal, in conversation, or sensual couples – archaic figures enduring in time. It is as if these figures spring out of his poems in order to meet characters from myth . . . characters incessantly fusing with later ones, never ceasing to exist in collective memory.

Back with Beckett – whose grandparents, I learn, were named Beckett and Robinson, as were mine on my mother’s side – I come across an extract from a letter by the publisher T.M Ragg at Routledge, which strikes me as an example of something you would never hear from a major publisher’s office nowadays.

Beckett’s novel Murphy was rejected by countless publishers on both sides of the Atlantic, Beckett “keeping a list, as reports came in, in his ‘Whoroscope’ notebook of the publishers whom he knew had rejected it. He almost lost count.” Eventually the book was recommended to Routledge by the painter-writer Jack B. Yeats, and one of the editors, Mr Ragg, read it in a single day while ill with gastric flu. All the miseries of his complaint were forgotten in his enthusiasm, he wrote, in his letter to Yeats, and he added:

I want to publish it, and I am seeing Reavey (Beckett’s agent) tomorrow to talk the matter over with him. I am afraid there is no doubt it is far too good to be a big popular or commercial success. On the other hand it, like your own book, will bring great joy to the few. Thank you very much for introducing it to me.

When I read that I had a brief fantasy of ever receiving such a letter from a major publisher in this day and age. Absolutely unthinkable. Imagine Random House or HarperCollins employing the loony criterion of ‘bringing great joy to the few’.

So thank the stars there are still small publishers like CB Editions, who produce lovely books for discerning readers, on precisely the criterion employed by Mr Ragg when he published Beckett’s Murphy. Their list may be small, but the range and quality of the books they produce is never less than excellent.