Post-canícula promenade

The howling of the village dogs has calmed down over the past week, due to the passing of the canícula (named for the dog star, Sirius, and its associated theme of mad dogs/midday sun, hence also ‘dog days of summer’) – that period of extreme heat that peaks here at some point between late July and mid August; and while it is now still hot, it is not unbearably hot. With this in mind I suggest to my friend and neighbour Joan Castelló that we might profitably do a hike from the monastery of Sant Quirze, near the village, across the mountains to Portbou. It seems a reasonable proposition, given an early start. We reckon we might even get to Portbou by lunchtime.

So, Joan, my daughter Sioned and I set off at 6.30, deposited at the monastery by Mrs Blanco, who has decided to sit this one out (on the beach, and somewhat later than 6.30), and we begin the calf-wrenching ascent to the first pass, Coll de Pallerols. Despite the mist, we arrive at the pass an hour later drenched in sweat, and I already feel as though I have spent an uninterrupted week in a Turkish bath, but having got this far there is no option but to press on. I keep wanting the mist to clear, as there are magnificent views across the peaks, and although the Alberas are small mountains compared with the Pyrenees of the interior, they are still dramatic in juxtaposition with the sea.

So, Joan, my daughter Sioned and I set off at 6.30, deposited at the monastery by Mrs Blanco, who has decided to sit this one out (on the beach, and somewhat later than 6.30), and we begin the calf-wrenching ascent to the first pass, Coll de Pallerols. Despite the mist, we arrive at the pass an hour later drenched in sweat, and I already feel as though I have spent an uninterrupted week in a Turkish bath, but having got this far there is no option but to press on. I keep wanting the mist to clear, as there are magnificent views across the peaks, and although the Alberas are small mountains compared with the Pyrenees of the interior, they are still dramatic in juxtaposition with the sea.

We pass small circular shepherds’ huts, a variation on a theme found all around the Mediterranean as well as in the British Isles, and just over half way, as the sun finally breaks through the cloud, we find ourselves in an enchanted deciduous woods, remarkable for those of us who live on the south-facing flanks of the Pyrenees, but common enough on the north-facing French side.

We pass small circular shepherds’ huts, a variation on a theme found all around the Mediterranean as well as in the British Isles, and just over half way, as the sun finally breaks through the cloud, we find ourselves in an enchanted deciduous woods, remarkable for those of us who live on the south-facing flanks of the Pyrenees, but common enough on the north-facing French side.

Following the border between the two countries for much of our walk, we start descending towards a point where the sea spreads ahead of us, spearheaded by a final mountain ridge, with Cerbère on the French side, and Portbou on the Spanish. The landscape provides a natural frontier, supposedly, (but not to the Catalans, who feel that both sides belong to them, rather than to either nation state).

It is at this point that a new feature has been added to the landscape: a large placard informing walkers in four languages that the renowned German philosopher and critic Walter Benjamin passed this same way on his flight from the Nazis in 1940 (see post for 7 August). The route has been renamed ‘Passage of Liberty’. Fine words, but confusing too – since the passage to liberty was traversed in the opposite direction often enough during and after the Spanish Civil War. They must mean a flexible passage of liberty, bi-directional, depending on your fancy or the pressures of historical necessity.

I applaud the honours due to Walter Benjamin, but cannot help feeling the Portbou civic administration might be milking this one, perhaps in pursuit of a new strain of intellectual tourism, no doubt attracting Euro-funding at the same time as raising the little town’s profile considerably, especially compared with the cultural paucity of the resorts further down the Costa Brava. In fact ‘Literary Landmarks of the Costa Brava’ might have considerable market potential: already there is a new statue to the Catalan poet Josep Palau i Fabre at nearby Grifeu beach. How long before Blanes starts selling itself as the home of Roberto Bolaño, and turning the Botanical Gardens there into a Santa Teresa theme park with 2666-themed dodgem rides and a Savage Detectives Treasure Hunt?

Our walk ended, as we might have predicted, far later than we wanted it to, in far too much heat. Seven hours after setting out we staggered onto the beach at Portbou and fell into the sea.

What is a Classic?

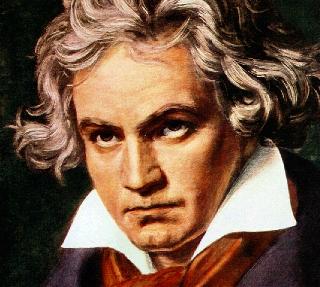

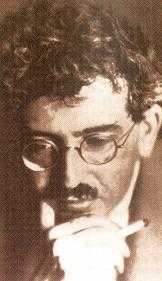

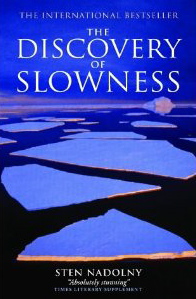

A couple of days ago I blogged about John Franklin’s moment of clarity while listening to a late Beethoven sonata in 1845, less than twenty years after it was composed. The music had – according to Sten Narodny’s account in The Discovery of Slowness – an epiphanic effect on the explorer, and in the novel he is made to endure a sublime moment of self-realisation.

Then yesterday, reading J.M. Coetzee’s essays, I come across an autobiographical anecdote of how Coetzee, at fifteen years of age, heard harpsichord music drifting across the garden fence from a neighbour’s open window in his Cape Town suburb, and the effect this had on his life. The music was from Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier and, writes Coetzee: “As long as the music lasted, I was frozen, I dared not breathe. I was being spoken to as music had never spoken to me before.” This despite the fact that his family home was bereft of music, that he received no instruction in music, that classical music above all was “sissy” and regarded by Coetzee in a “somewhat suspicious and hostile teenage manner”.

But somehow Bach’s music breaks through to the boy, “speaks to” him, as Coetzee puts it. And in his essay ‘What is a Classic’ the adult author wonders whether his adolescent response to the music back in 1955 was “truly a response to some inherent quality in the music rather than a symbolic election on my part of European high culture as a way out of a social and historical dead end.” Since the essay’s title marks it out as a response to T.S. Eliot, and Coetzee is concerned about the emergence of the term Bach as a touchstone, and a classic as being, in at least one sense, ‘that which survives’, we end up depending (argues Coetzee) on criticism to define and sustain notions of the classical.

Which is all true, but by resorting to an argument about the nature of the classic (and for perfectly valid reasons) Coetzee rather avoids answering the question that he originally posed, about whether Bach ‘spoke to him across the ages’ or whether he, Coetzee, was (unwittingly perhaps) choosing high European culture and the codes of that culture in order to escape his class position in white South African society, and the historical dead-end represented by his immediate environment.

But despite the excellence of Coetzee’s writing and argumentation, I remain puzzled.

Somewhere in his writings, possibly The Curtain – I am away from my library right now and cannot check – Milan Kundera speculates on the kind of reception that would be given to a work of Beethoven’s were it written by a contemporary composer and performed as though it were a new composition. Kundera asserts that such a piece of music would be subject to ridicule. No one would take the music or its composer seriously. Since all cultural artefacts are a product of their historical and cultural moment, a ‘contemporary’ writing of the opus 111 piano sonata by a modern composer would fail to have the effect on a latter-day John Franklin, or by extension, on you or me.

How does this play out in relation to Coetzee’s adolescent experience? What if The Well-Tempered Clavier was the work of a brilliant but geeky composer of the 1950s who despised the tendencies of Romanticism and Modernism and elected to write ‘like’ J.S. Bach? The sequence of sounds would be identical, but would the effect be the same? Does this mean that young Coetzee’s response to Bach’s quintessentially classical music had its profound effect– even though he did not know what he was listening to?

How can this come about? Are our responses to music entirely subject to cultural and historic provenance? Is a particular arrangement of sounds only a cipher, a means by which a listener measures him or herself as a participant-observer in cultural experience?

This raises many other questions, including obvious ones such as the way we ditch and discard some music – even find it unlistenable – over the course of years, while other music we can listen to almost any time. But for the moment, Kundera’s question and Coetzee’s musical awakening in 1955 present a paradox that I am struggling to reconcile.

Any comments welcome.

Restless Geography

The blog is founded on the idea that Blanco never spends too much time writing a post, unless it is an article, review or poem that has already been prepared or published elsewhere (i.e. recycled work, of which there is an irregular smattering). In other words the motivating principle is of spontaneity, of always allowing myself, in my writing, to move where the mood takes me, so I do not necessarily end up in a place where I thought I was going: I would go so far as to say that was the whole point of the blog – to begin a thought process and see where it takes me. This will sometimes mean that the title of the piece only makes sense in terms of something that appears towards the end, or is a fleeting thought that arises as a consequence of something in the blog that is not fully explored.

So what we have is a kind of diary, alongside a series of reflections – precisely as the subtitle proclaims – on the mutable universe. Like most things concerning the genesis of the blog, the words came without conscious forethought: but ‘mutable’ is key here: I want the blog to act as an archive – very much in the spirit of the work of my friend, the painter Lluís Peñaranda – of mutability, of fleetingness, of transience. The transience of those things that we explore, and the transience of ourselves.

Actually, the most apt description of what we have is labyrinth. A labyrinth is not only a metaphor for the questing self, and a means of self-transcendence: it is also a way of getting purposefully lost, of going up blind alleys, of plunging deeper into one’s own lack of knowledge and coming back with something unknown, of finding surprising routes to places we never intended going. Of noting that the exit to the labyrinth is sometimes marked Entrance to the Labyrinth.

And of observing what goes on inside the labyrinth when the geography will not stay still.

To be continued.

I set out on a journey, but the geography would not stay still, and I ended up somewhere I hadn’t intended going.

‘Restless Geography’ from Sad Giraffe Café (2010)

A State of Wonder

In Sten Nadolny’s fine novel The Discovery of Slowness, the polar explorer John Franklin attends a recital of Beethoven sonatas on 9th May 1845. During the performance of the opus 111 sonata, “John felt he was actually meeting the fine skeleton of all thought, the elements, and the ephemeral nature of all structures, the duration and slippage of all ideas. He was imbued with insight and optimism. A few moments after the final note sounded he suddenly knew, There is no victory and no defeat. These are arbitrary notions that float about in concepts of time invented by man.”

While it might not be a realistic objective for most of us to achieve this state of immaculate insight very often – supermarket shopping, tax statements, the MOT, and for some of us the basic dignity of finding work, all this stuff gets in the way – we are all gifted these moments of clarity, we all catch the occasional glimpse, and if we are lucky we build up a store of such experiences, an archive of rare encounters with the transcendent. Normally such moments are not instructive to others, nor in fact are they easy to elucidate or express. But cumulatively they create a cluster, form a chain reaction, each epiphany linked mysteriously to all those that have come before, in a steady act of making. I am reminded of the words of the pianist Glenn Gould that I quoted in The Vagabond’s Breakfast: “The purpose of art is not the release of a momentary ejection of adrenalin but rather the gradual, lifelong construction of a state of wonder and serenity.”

Sometimes it swings this way, and sometimes the world has other plans.

The Discovery of Slowness

Met up with this tortoise on a walk in the Albera range yesterday morning. The Alberas are home to the last natural population of the Mediterranean tortoise (Testudo h. hermanni) in the Iberian Peninsula, and they are a protected species.

One of my walking companions, a friend and local farmer with family affiliations to the land around here that go back many generations says that its size indicates it is at least a hundred years old. Its markings suggest it is a male. This means Tortoise was wandering along these paths when our chaps went over the top on the first day of the Somme, when Lenin’s revolutionaries stormed Petersburg. By the time of the Spanish Civil War, when these hills were teeming with refugees and war-wounded, Tortoise would have marked out his territory and become familiar with every ditch and rock and bush on his patch.

He was sunning himself when we approached, and retreated into his shell to avoid the attentions of our dog. But once the dog was kept away he re-emerged to take a look at us. Then, having determined that we didn’t pose a threat, he set off down a bank, at considerable speed – well, relatively speaking – negotiating stones and clumps of bush with clumsy determination. He moved, I would say, with deliberation and with definite purpose, although he was not going to be hurried.

Which brings me neatly to the point. I am reading Sten Nadolny’s The Discovery of Slowness. The book is about the life of John Franklin, the nineteenth century polar explorer. John had issues as a child, and as a young man, concerning his slowness. The novel catalogues his subtle protest at the institutionalised imposition of quickness or speed. He struggles single-handedly to legitimize his own slowness, and in his own fashion, he succeeds. It is a wonderful novel, beautifully translated by Ralph Freedman. To press my recent argument in this blog about literature in translation, I should point out that the novel was published in German in 1983 and had to wait twenty years before appearing in English in 2003. In the meantime two hundred thousand crap novels were published in English, which no one will ever remember.

Some of my favourite lines from The Discovery of Slowness so far:

Some of my favourite lines from The Discovery of Slowness so far:

“A good story doesn’t need a purpose.”

“John was in search of a place where nobody would find him too slow. Such a place could still be far away, however.”

“He wandered through the town and pondered man’s speeds. If it was true that some people were slow by nature, this should remain so. It was probably not given to them to be like others.”

“There are two kinds [of seeing]: an eye for details, which discovers new things, and a fixed look that follows only a ready-made plan and speeds it up for the moment. If you don’t understand me, I can’t say it any other way. Even these sentences gave me a lot of trouble.”

And, of course, Achilles and the tortoise: John’s old schoolmaster, Dr Orme, attempts to explain one of the Paradoxes of Zeno:

“‘Achilles, the fastest runner in the world, was so slow that he couldn’t overtake a tortoise.’ He waited until John had fully grasped the madness of this assertion. ‘Achilles gave the tortoise a head start. They started at the same time. Then he ran to where the tortoise had been, but it had already reached a new point. When he ran to the next point the tortoise had crawled on again. And so it went, innumerable times. The distance between them lessened, but he never caught up with the tortoise.’ John squeezed his eyes shut and considered this. Tortoise? he thought, and looked at the ground. He observed Dr Orme’s shoes. Achilles? That was something made up.”

That was something made up. The whole ‘Achilles and the tortoise’ thing is made up. It’s a nonsense, and I remember thinking the same thing as a boy myself. It is the kind of idiot sophism upon which Western Philosophy seems to be founded. Who believes this stuff anyway? I had the same feeling as John Franklin when I came across Zeno’s Paradox – no doubt via Aesop’s fables – which provides the prototype of the tortoise story.

As Aristotle summarized: “In a race, the quickest runner can never overtake the slowest, since the pursuer must first reach the point whence the pursued started, so that the slower must always hold a lead.”

But who says the pursuer must reach the point whence the pursued started? Why? Why does everyone accept these assertions as though they were a given when they read these ancient texts, whether Greek or Chinese, the kind ‘steeped in ancient wisdom’? Why can’t the pursuer avoid the point at which the pursued started? Why does no one ask these obvious fucking questions? Is it some kind of convention, by which we all suspend our critical faculties and pretend to be idiots so as to have someone’s pet theory proved right, be it Zeno, Aristotle or Christopher Columbus? But I digress.

It’s no longer useful, as a universal principle, to assume that fast is necessarily better than slow. Fast food, fast sex, fast money, faster death. I rest my case. We all know we can do speed, and what is costs.

I believe that in an era where speed is probably a more highly-valued commodity than love, The Discovery of Slowness delivers a salutary message.

An Aleph in my hand

Drove up to the Gers, in France, to visit the brother. It is a four-hour drive in our old Citroën, which starts rattling if required to exceed about 75 mph. It is hot, and the car has no air conditioning, so we leave early. The autoroute up to Toulouse is very dull, but once you get on the B roads west of the city the countryside is fine and lovely, with rolling hills and great fields of sunflower and of maize unravelling to the horizon.

Now maize, or corn, has a special place in Blanco’s heart. For two summers, in 84 and 85, I worked in the maize fields of the Gers on the annual castrage, or castration The picture on the right, incidentally, is of a maize field in Lichtenstein, not the Gers, but one maize field looks pretty much like any other). The odd practice of castration, which was explained to me countless times but which I never fully understood, involves ripping the male part from its socket high on the plant’s stem, and casting it away, which ensures that the next year’s crop will not be contaminated with bâtards, or bastards. Little bastards, or salauds, I used to call them. Back in the day, the work would be done by teams of migrant workers or else down-and-outs like myself eager for a few days work in the fields in convivial company and with good pay. Often the work would come with board and lodging. The Gers is also a wine (and Armagnac) producing region, so there was always plenty to drink. I have very fond memories of those two summers castrating maize, even though the work could be very dull, walking down those interminable rows, ripping out all those male genitals and tossing them away. Of all the most meaningless jobs I have done, the castration is pretty high up on the list. Because of the utter tedium it inspired, I once had a fantasy of discovering an aleph while working on the maize. Of feeling my toes come into contact with something cold and hard and round, stooping to pick it up, and finding I held an aleph in my hand.

Aleph is the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet. An aleph, for those of you who have not read Borges, is a small and miraculous construct that contains within it the entire content of the universe (and all possible universes). Put another way, an Aleph is a point in space that contains all other points. Within it can be seen everything in the universe from every angle simultaneously, apparently without distortion, overlapping or confusion. It is, as you might imagine, incredibly heavy to hold in one’s hand. As you might also imagine, finding an aleph is a pretty rare thing, certainly not an everyday affair. Finding one in a field of maize, then, would have constituted a considerable improvement to the outcome of a day’s work. But it never happened. Maybe, one day, I will have to put it in a book instead. I have however, written a piece about working on the maize, which I reproduce below, with apologies to those who were listening when I said I was not going to use the blog simply to flaunt my own literary creations – Did I say that? Am I imagining it? – but since I am in the Gers this fine Sunday morning, and since Riscle is a real town in this département, I thought I should include it.

Riscle

The maize fields are vast and sad in the wind. The tops of the plants bend unwillingly. I know what happens here. It has always remained a secret until now. But for the sake of friendship I will tell you. In July, the castrators will come. They will rip out the genitals of the male plants, so that the females cannot be impregnated and raise bastards. At least, that is what the locals tell the workers. The real story of the maize is more violent still. Groups of young men and women meet after dark, drink absinthe, and fuck beneath the summer moon. In the morning, tired and spent, they retire to the Café D’Artagnan for coffee with milk and croissants. They are recruited by farmers, who drive them to the maize fields. There they begin the tedious task of le castrage. The young men begin to feel uncomfortable with this de-seeding of the male plants. Their discomfort translates into physical symptoms: aching sides, persistent headaches and vomiting. Later they will complain of spontaneous ejaculation, green sperm, and will participate in outbreaks of frenzied violence towards other males. In early spring the babies are born: little maize-people, with an obsolete immune system inherited from Aztec forebears. The babies all die before July, when the castration begins again.

From Sad Giraffe Café (Arc, 2010)

The Black Lake of Antonio Machado

El ojo que ves no es

ojo porqué tú le veas

es ojo porqué te ve.

The eye you see is not

an eye because you see it

but because it sees you.

This morning, reading some poems by Antonio Machado, I am reminded of a trip we took to the province of Soria one July a few years back. Machado was for many years a schoolmaster in Soria, and wrote many fine poems about the place. I saw the trip as a kind of homage, but a purely literary excursion was out of the question, so we combined it with a visit to Navarra, and made a round trip.

We had driven down from the fiesta at Pamplona, and as we entered Soria after a two hour drive the temperature was registering forty-three degrees. Too hot to stagger around the town, we set out to Vinuesa, the nearest village to Machado’s Laguna Negra (Black Lake). This is walking country, between 1500 and 2000 metres in altitude: woods of dense beech and cedar, streams, waterfalls and lakes, in stunning contrast to the interminable dust-blown expanses of the meseta.

Machado´s narrative of the Laguna Negra concerns a local farmer who was murdered by his greedy sons in anticipation of their inheritance, and subsequently thrown into the lake, with weights attached to his body. The parricides themselves suffer an ignominous retribution, losing their way in the mist one night, falling and drowning in the very lake in which their murdered father was dumped. Wolves are said to surround the lake at night, symbollically howling out the bad sons’ shame. Machado’s poetry conjures this desolate and otherworldly landscape to grim perfection.

It was already dusk by the time we reached the lake, and we wandered among the huge boulders that mark its circumference. There were more beech woods and glades that centred on a pair of massive rocks. I thought of native Austrailian beliefs that a person can become incorporated into the landscape on their deaths, and began to consider the parricidical sons in a new way. Scrambling around this silent expanse of black water as the light fails, one could sense the presence of the legend like a virus on the air. Gazing up at the high rim of the volcanic crater the occasional tree juts out at an impossible angle. The stench of murder, the pervasive notion of return to the same deathly reserve of water, unmoving now except for a shimmering of ripples when a long black snake zig-zags between two small promontories. I like the place, but something tells me we should leave. Tripping over exposed tree-roots in the darkness we find the path again and descend to the car.

Machado has a more local significance, here in the borderlands of the Alt Empordá. In 1939, as the Civil War came to a bloody close, Machado, who had been active in support of the Republican cause, made his way to the frontier, very ill, and accompanied by his elderly mother. He tried to cross into France, but was held up because his papers were not in order. His attempted escape to France was echoed, in reverse, a year later by Walter Benjamin, fleeing from the Nazis. I tried to capture this near-synchronous flight in a prose poem once, see below. In actual fact Machado died in Collioure, a few kilometres north from Cerbére, while Benjamin made the seven kilometres south across the mountains to Port Bou (see post for 7 August).

Synchronicity

Here’s what happened. Antonio Machado, celebrated Spanish poet, was fleeing Spain and the advancing Francoist army. After a desperate journey through a defeated Catalunya, he arrived at the French border village of Cerbère. It was raining heavily. The authorities would not let him into France. His papers, they said, were not in order. Drenched by the rain and sick, Machado took refuge in a small hotel. He left the building once only, to watch the fishing boats in the small harbour. Shortly afterwards, he died. It was Ash Wednesday, 1939.

The following year, Walter Benjamin, the noted German polymath and essayist, arrived in the same village, coming from the opposite direction. He was fleeing the Nazis, trying to get to Spain. From Spain he hoped to catch a boat to America. The authorities would not let him leave France. His papers, they said, were not in order. Despairing at the state of the Europe he could not leave, while eluding the holocaust of which he would no doubt have been a victim, Benjamin chose to take his own life, using poison.

Antonio Machado was born on the same day – July 26th 1875 – as Carl Jung, the originator of the theory of synchronicity. Walter Benjamin had a low opinion of Jung, considering him to be a supporter of the Aryan myth, and accusing him of doing ‘the devil’s work’.

From ‘Walking on Bones‘ by Richard Gwyn (Parthian, 2000)

If you would like to read more on Machado, there is a useful article by Derek Walcott in the New Yorker, although you may have to pay, depending, like so many things, on who or where you are.

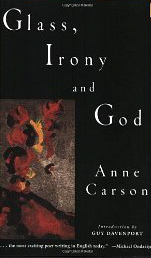

Coetzee’s Foe

‘When I was young there were degrees of certainty’: these words I quoted the other day from Anne Carson evoke a sense of certainty instilled by the repetition of known stories. In childhood, if the world makes sense at all it does so because the stories we hear about it cohere. The ‘storied world’ takes on new meaning when applied to the central character of J.M. Coetzee’s Foe, one Susan Barton, who, having travelled to Brazil to search for her kidnapped daughter, is cast adrift by mutineers, and washed up on an island inhabited by a dull and grumpy ‘Cruso’ (who after briefly becoming her lover, dies on her) and a mute Friday, whose tongue has been cut out, according to Cruso, by slavers.

Coetzee’s book is a story about the making of stories. Susan, on her rescue and return to England, writes an account of her adventure and sends it in instalments to the famous writer Mr Daniel Foe, while living in penury with Friday, first in rented accommodation in London, then on the open road as vagrants. She convinces herself – what a common fantasy – that the telling of her story will make her fortune:

“The Female Castaway. Being a True Account of a Year Spent on a Desert Island. With Many Strange Circumstances Never Hitherto Related.” Then I made a list of all the strange circumstances of the year I could remember: the mutiny and murder on the Portuguese ship, Cruso’s castle, Cruso himself with his lion’s mane and apeskin clothes, his voiceless slave Friday, the vast terraces he had built, all bare of growth, the terrible storm that tore the roof off our house and heaped the beaches with dying fish. Dubiously I thought: Are these enough strange circumstances to make a story of? How long before I am driven to invent new and stranger circumstances: the salvage of tools and muskets from Cruso’s ship; the building of a boat, or at least a skiff, and a venture to the mainland; a landing by cannibals on the island, followed by a skirmish and many bloody deaths; and, at last, the coming of a golden-haired stranger with a sack of corn, and the planting of the terraces? Alas, will the day ever arrive when we can make a story without strange circumstances?

“The Female Castaway. Being a True Account of a Year Spent on a Desert Island. With Many Strange Circumstances Never Hitherto Related.” Then I made a list of all the strange circumstances of the year I could remember: the mutiny and murder on the Portuguese ship, Cruso’s castle, Cruso himself with his lion’s mane and apeskin clothes, his voiceless slave Friday, the vast terraces he had built, all bare of growth, the terrible storm that tore the roof off our house and heaped the beaches with dying fish. Dubiously I thought: Are these enough strange circumstances to make a story of? How long before I am driven to invent new and stranger circumstances: the salvage of tools and muskets from Cruso’s ship; the building of a boat, or at least a skiff, and a venture to the mainland; a landing by cannibals on the island, followed by a skirmish and many bloody deaths; and, at last, the coming of a golden-haired stranger with a sack of corn, and the planting of the terraces? Alas, will the day ever arrive when we can make a story without strange circumstances?

Thus Susan Barton is unwittingly made the mouthpiece for the story Defoe actually wrote (but she cannot). How poor Susan needs to satisfy the need to tell and tell, and yet not to cross that invisible line into mere ‘invention’. How curious that the confection of her story demands such truth-telling; and yet all around her are those whose very lives depend on the invention of fictions.

This is a book rich is allusion, and in stimulating reflection on the writer’s life. Here is Foe speaking to Susan: “You and I know, in our different ways, how rambling an occupation writing is; and conjuring is surely much the same. We sit staring out of the window, and a cloud shaped like a camel passes by, and before we know it our fantasy has whisked us away to the sands of Africa and our hero (who is no one but ourselves in disguise) is clashing scimitars with a Moorish brigand. A new cloud floats past in the form of a sailing-ship, and in a trice we are cast ashore all woebegone on a desert isle. Have we cause to believe that the lives it is given us to live proceed with any more design than these whimsical adventures?”

And here is the crux of it: all our lives are story; much of that story is conjecture, the rest invention. A tale heard in passing between sunrise and sunset. There is room for many more such stories. Or, as Coetzee’s Susan tells the mute servant Friday, after being confronted by a strange girl who insists she is Susan’s long-lost daughter:

“It is nothing, Friday . . . it is only a poor mad girl come to join us. In Mr Foe’s house there are many mansions. We are as yet only a castaway and a dumb slave and now a madwoman. There is place yet for lepers and acrobats and pirates and whores to join our menagerie.”

Even without the lepers and acrobats and pirates and whores, Coetzee has the patience to furnish a story that is both intriguing and beautifully crafted. And my copy now carries the invisible traces of a thousand other stories, and of a hot day in August.

Translation

All your stories are about yourself, she said, even when they seem to be about other people. I was not going to deny this, nor give her the pleasure of being right. So I quoted Proust, who said that writers don’t invent books; they find them within themselves and translate them. This seemed to do the trick, and she fell silent. I dipped my fingers into a bowl of scented water and started on the rice. An aftertaste of clay and leaves and metal took me by surprise. What is in this rice? I asked her. Mushroom stock? Shotgun cartridge? Earthworm? No, she said, peering at me through the candlelight, the stories that you haven’t written yet are in the rice. You must be tasting them.

Reading ‘Translation’ at International Poetry Festival of Granada, Nicaragua, February 2011.

Spanish version by Sadurní Vergès, read by Melisa Machado.

From ‘Sad Giraffe Cafe‘ by Richard Gwyn (Arc, 2010).

The Glass Essay

This morning, with the first light, I read Anne Carson’s long poem The Glass Essay, 38 pages and not a word wasted. Now every line feels engraved in my consciousness. What a rare occurrence this is. I sit up in bed, propped by a few cushions. Bed is a euphemism. We haven’t got around to buying a bed, in seven years. A mattress on the wooden boards, and a view across red rooftops to the bell-tower of the church. Early swallows skimming and diving. From time to time, while reading, I drift off, and occasionally it happens that I dream the words I have been reading, only to waken and find they are not the words on the page at all, but my own. So, reading Carson’s poetic discourse on Emily Brontë I drift into a dream where I am at the northernmost point of the north of a northern territory. Then I wake and continue to read. That way, reading is even more than usually a kind of collaborative experience.

This morning, with the first light, I read Anne Carson’s long poem The Glass Essay, 38 pages and not a word wasted. Now every line feels engraved in my consciousness. What a rare occurrence this is. I sit up in bed, propped by a few cushions. Bed is a euphemism. We haven’t got around to buying a bed, in seven years. A mattress on the wooden boards, and a view across red rooftops to the bell-tower of the church. Early swallows skimming and diving. From time to time, while reading, I drift off, and occasionally it happens that I dream the words I have been reading, only to waken and find they are not the words on the page at all, but my own. So, reading Carson’s poetic discourse on Emily Brontë I drift into a dream where I am at the northernmost point of the north of a northern territory. Then I wake and continue to read. That way, reading is even more than usually a kind of collaborative experience.

I used to write quite a lot of poetry, but these days I find that the effort it takes to ‘make verse’ – as though straining towards a truth more profound or more lasting than the truth of prose – is not necessarily justified, or justifiable. By whom do I mean justified? By what measure justifiable? I do not know, I really don’t. But, mainly, I write prose.

And then how good it feels, and how rare, to sink into and absorb a poem as fine as this one. There are three themes to it: the

aftermath of a love affair between the narrator and a man she calls Law (he has his echo in her therapist, a woman called Dr Haw), a theme which constitutes the near past. Then there is an account of the life of Emily Brontë, author of Wuthering Heights (the distant past). Finally, the poem is cast in a present tense in which the poet (or narrator) is paying an extended visit to her mother, who lives on a moor in ‘the north’. The majesty of the poem is the way in which Carson threads the three narratives in and around one another, guilefully working each one so as best to extract the full flavour of the other two. There is such skill (and yes, it does appear effortless, which means it was hard-earned) in the composition of the poem. I stand in awe of this writing. To give some impression of the quality, here are three short passages from a single page:

‘When I was young

there were degrees of certainty.

I could say, Yes I know that I have two hands.

Then one day I awakened on a planet of people whose hands

occasionally disappear –’

also:

‘It is stunning, it is a moment like no other,

when one’s lover comes in and says I do not love you anymore.

I switch off the lamp and lie on my back.’

also:

‘Emily had a relationship on this level with someone she calls Thou.

She describes Thou as awake like herself all night

and full of strange power.’

Earlier in the poem she writes:

‘I have never liked lying in bed in the morning.

Law did.

My mother does.

But as soon as the morning light hits my eyes I want to be out in it –

moving along the moor

into the first blue currents and cold navigation of everything awake.’

I too like to be awake at first light, but some days it is good to lie in with it, and read poetry as good as Carson’s.

‘The Glass Essay’ appears in Glass, Irony and God, published by New Directions (1995).

Walter Benjamin at Portbou

Yesterday an excursion to Portbou and a picnic on a nearby beach to celebrate the birthday of our dear friend Juliette. As usual our large and straggling international party effectively turned a section of the beach into an ever expanding occupied zone, and a feast of fresh fish, chickens, salads, melon, cake, wine, coffee and cigars unravelled, the younger hooligan element ensuring total isolation from other beachgoers, which, on this particular beach was no problem, as it is not easily accessed except by the more adventurous or robust sun-seeker.

I do not know Portbou all that well, but have always felt drawn to it in a strange way. It is a shy place, giving off a sad, mysterious energy; a border town that, with the cessation of European frontiers, has lost its role as a centre for customs control. All that remains is its vast and cavernous railway station.

We once ate here, late at night, about ten years ago, and Mrs Blanco and I fell into conversation with the young Moroccan waiter, no doubt an illegal, who had got this close to France in search of a better life, and had decided to stay. We left the restaurant as it was closing up, and headed for the car, which was parked a few streets away. We were about to pile in, when the young waiter appeared, panting, with our younger daughter’s jacket, having run down the streets searching for us. That reassuring incident helped formulate my ideas about the place, of a small, neglected border town with heart, where people end up by chance rather than by choice.

The coast road runs down the final miles of France’s ‘côte vermeille’ from Collioure, a charming and now very chic resort, for fifty years the home of the English writer of historical fiction Patrick O’Brien. In my vagabond days I once walked this frontier road on a baking June afternoon, arriving bedraggled and exhausted on the Spanish side, where the friendly guard, who was about to be relieved from his shift, took pity on me and suggested we adjourn to the nearby bar for a beer, which turned into many. He dropped me off in Portbou later that night after a hair-raising 7 km descent in his old Simca, and I slept on the beach. The border post no longer exists and the bar is boarded up.

But Portbou is mostly famous as the final destination of the German philosopher and critic, Walter Benjamin. On 25th September 1940, following seven years exile in France and 28 changes of address, Benjamin, along with two other asylum-seekers and their guide, arrived exhausted at Portbou after a trek across the mountains from Banyuls. Benjamin carried a provisional American passport issued by the US Foreign Service in Marseilles, which was permissible for land travel across Spain to Portugal, where he aimed to catch a ship to the USA. However, he was prevented entry to Spain since he had no French exit visa. Perhaps because of his evident ill-health, perhaps because of a border guard’s Republican sympathies, his return to France was postponed until the next day and he was allowed to spend the night in an hotel, the Hotel de Francia, rather than in police custody. The following day he was found dead in his room.

I didn’t realise that Benjamin killed himself by taking an overdose of morphine (he had a supply with him, for this eventuality): I had read elsewhere that he took poison, surely some kind of euphemism. If you’re going to go, morphine must be preferable to having some hideous acid gnawing through your guts.

The following account is taken from a dedicated website on Walter Benjamin at Portbou, The Last Passage:

‘If they had arrived a day earlier, they would not have been refused entry to Spain: a change of orders had been received that very day. If they had arrived a day later, they would probably have been allowed in. The Gurlands, at any rate, Benjamin’s travelling companions, were permitted to continue their journey, although perhaps this was due in part to the impact made on the local authorities and police by the death of ‘the German gentleman’. A few days later, Henny and her son Joseph boarded a ship for America.

Benjamin left a suitcase with a small amount of money in dollars and francs, which were changed into pesetas to pay for the funeral four days later. In the judge’s documentation the dead man’s possessions are listed as a suitcase leather, a gold watch, a pipe, a passport issued in Marseilles by the American Foreign Service, six passport photos, an X-ray, a pair of spectacles, various magazines, a number of letters, and a few papers, contents unknown, and some money. . .

. . . In Portbou Walter Benjamin put an end to seven years of exile and the possibility of a new future in America. For the local people, the death of the mysterious foreigner became shrouded in legend, but for others it was a freely chosen exit, an authentic rebellion against the Nazi terror by one of the most lucid thinkers of modernity. However, no aspect of Benjamin’s death is definitively closed. One hypothesis holds that Benjamin was killed by Stalinist agents (the full arguments of this hypothesis is collected by Stuart Jeffries in his ‘Observer’ article ‘Did Stalin’s killers liquidate Walter Benjamin’. What is more, his guide across the mountains, Lisa Fittko, who died in 2005, referred on many occasions to the suitcase with a manuscript that Benjamin jealously guarded as a valuable treasure. Did it contain his final manuscript? The suitcase was never found: its fate is unknown, and in the judge’s report of the property of the deceased there is no mention of any manuscript.’

The memorial ‘Passagen’ at Portbou was designed by Israeli Artist Dani Karavan, and an inscription reads that “it is more arduous to honour the memory of the nameless than that of the renowned. Historical construction is devoted to the memory of the nameless.” Puzzling, that last sentence, and possibly meaningless, certainly untrue, since history forgets the nameless masses, definitively. But the memorial itself is spectacular, and a video clip, attached below, gives some idea of the approach and setting, enclosed by the mountain landscape and opening out onto the sea.

In the nearby gated cemetery, on Benjamin’s gravestone, there is a quotation from Thesis VII of his ‘Theses on the Philosophy of History’: ‘There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism‘.

Naked Man with Pit-Bull

Imagine my surprise yesterday, when visiting one of our favourite beaches with friends (where I intended doing a little underwater  fish-gazing with mask and snorkel) I spied a naked man washing his pit-bull in the shallows. Bending over it, lovingly washing its flanks in the plankton-rich waters of the western Med.

fish-gazing with mask and snorkel) I spied a naked man washing his pit-bull in the shallows. Bending over it, lovingly washing its flanks in the plankton-rich waters of the western Med.

This is not a nudist beach, and while I have no objections to nakedness in principle, I do believe it has its proper place in civilized society. I know that many people think differently and they are entitled to set up their own recreational centres where nudism is de rigueur and you can even spend your summer holiday in such places, renting a chalet or a luxury apartment, surrounded by other nude persons. You can go shopping in the site supermarket with nothing on, and sit in the bar bollock-naked sipping your evening cocktail. Michel Houellebecq, once known as the enfant terrible of French Literature (and actually quite a decent poet, as his recent collection ‘The Art of Struggle‘ impressed on me) has written about such places at tedious lengths in his fiction.

But on a regular, costumed beach, it is my belief that bathers should wear a swimming suit. I have no particular objection to bikini tops being removed, but even that is probably only a matter of having become accustomed to it over many years. In the final analysis, I do not mind too much about public nudity either way, and it is really not my business what consulting adults prefer to do. But to have fully grown men parading with all their tackle hanging free, when there are young children roaming the sands around them peering inquisitively at the exposed genitalia, is – while filled with comic potential – not a vision I relish or one in which I wish to share. Nor are beer bellies and sagging tits, and heaving folds of cellulite, but here again I might stand accused of some kind of aesthetic fascism, and should probably stop there.

So, gentle reader, rather than offend your sensibilities by showing the perpetrator of this act of aggressive nudism (who I suspect was French), I have appended a picture of the stretch of beach an hour or so after he had left.

Personally, I like donning mask and flippers and swimming down, peering beneath the surface of the sea, at the underwater flora and rock formations, the hundreds of brightly coloured fish, starfish, octopi and the many other wondrous sights so gloriously described in the films of the late Jacques Cousteau.

PS Mrs Blanco has pointed out that this comes across as a rather pompous and stuffy post. I think, therefore, that I cannot have conveyed my point about the man with the pit-bull very well. To be blunt, there was something fishy about both his ostentatious nudity and the manner in which he washed his dog, as if, not to put too fine a point to it, he were accustomed to more intimate relations with the beast. I find it hard to put concisely: but there was an insalubrious quality to his washing of it that had to be observed in order to be appreciated.

And finally, as Alessandra has pointed out, dogs are not allowed on Catalan beaches in the summer. A fair point.