Poems for staying at home (Day 7)

Today’s house is a childhood home in Santiago de Chile, revisited by the poet Verónica Zondek after years in exile, following the Pinochet dictatorship. The poem burrows and weaves its way through the dusty enclaves of the past, trying to make sense of ‘progreso’, which as well as meaning ‘progress’, is an area of Zondek’s native city.

You can listen to Verónica Zondek reading ‘Progreso’ on video below.

Progress

I know it without betrayal or evidence.

This is my house and yet it’s not.

Memories boil and bubble from step to step

and towering up to the 15th floor, get lost in the nothingness of sky

grey now and not the blue of No, I remember.

Three stairs with footprints and mud in the entrance

a cranky horseshoe on a nail in the door

and an aura that protects the family’s breath.

Yes, a chequered floor in the kitchen

a spruce chess board and Clorinda for thorough hygiene

bread that is promptly kneaded in memory

an oven that bakes the cake of childhood’s clay.

Yes, I remember the shifting shade of the shutters

and the eternal counting of lines in sleeplessness

and the voices from heaven

and also the others

those

those that reprimand

those that invade my head in supposed sleep

and make me read by the light of a torch

so that God willing panic doesn’t spread.

Yes, a grumbling staircase absorbs my school shoes

and reveals and flaunts that strident independence.

Yes, once loud and swaggering,

swelling with laughter and tears and the nerves of a beginner,

hooked, like everyone, in the eye of their own time.

So many days wandering in the desert of the home

concentrating on the alien talk of adults

filling the emptiness that occasionally swells

to later stitch together a story, only intelligible,

of course, in one formerly so sane,

and that wardrobe of surprises in the corridor

nothing less than an ancient sea in full surge

buried beneath one and seven keys of Cerberus

silence and secret seldom ajar

pirates’ chest and cave of cursed elf

wishing for illness so as to break the seal

and the shining white walls of adobe

naked and without a skin when the earth shakes

and the books that collapse on your head

and the invasion of master bonesetters

and the dust and the mess and the cornered silence

and the tremendous bother of hustle and bustle.

Vanity.

Vanity of the matter that shelters memory

like a silent treasure box surrendered to the digger.

Progress

cold and beautiful like the blue ice of glaciers

that barely able and with the road’s consent

neither knows nor asks

and takes control and buries beneath the thunder of doing

the loveliest thought and chained to the fire

that already once was snatched from us.

(Translated by Richard Gwyn)

Progreso

Lo sé sin traición ni documento.

Esta es mi casa y ya no es.

Hierven y suben los recuerdos de escalón en escalón

y altísimos hasta el piso 15 se pierden en la nada del cielo

gris ahora y no azul del no, ya recuerdo.

Tres peldaños con pisadas y barro en la entrada

una herradura quejumbrosa en un clavo de la puerta

y un aura que defiende el hálito familiar.

Sí, un piso cuadriculado en la cocina

Un pulcro tablero y una Clorinda para el buen aseo

Un pan que presto se amasa en la memoria

Un horno que cuece la torta del barro infantil.

Sí, recuerdo la sombre alternada de los postigos

y el eterno recuento de líneas en desvelo

y las voces celestiales

y también las otras

esas

las que amonestan

las que invaden mi cabeza en reposo pretendido

y obligan la lectura a la luz de una linterna

para que Dios mediante no cunda el pánico.

Sí, una quejumbrosa escalera recibe mis zapatos colegiales

y destapa y ondea esa independencia de pelo en pecho.

Sí, una entonces bravucona y vociferante

una hinchada en llanto y risa nervios de principiante

una colgada como todos en el ojo del tiempo propio.

Tantos y tantos días errantes en el desierto del hogar

concentrada en el decir aparte de los mayores

llenando el vacío que a ratos hincha

para luego hilvanar una historia en demasía propia

inteligible, por supuesto, en un otrora tan cuerdo

y ese armario con sorpresas en el pasillo

no otra cosa que un mar antañoso con su completo oleaje

encerrado bajo una y siete llaves de cancerbero

silencio y secreto pocas veces entreabierto

baúl de piratas y cueva de duende maldito

deseando la dolencia para violarle el sello

y las albas paredes de adobe

desnudas y sin cáscara en medio de las tembladeras

y los libros que derrumban sobre la cabeza

y la invasión de maestros componedore

y el polvo y el desorden y el silencio arrinconado

y la tremenda molestia del ajetreo.

Vanidad.

Vanidad de la materia que acoge el recuerdo

cual cofre silente entregado a la retroexcavadora.

Progreso

frío y bello como el hielo azul de los glaciares

que pudiendo apenas y con la venia de dónde la carretera

tampoco sabe ni pregunta

y toma la sartén por la mango y entierra bajo el trueno del hacer

el bellísimo pensar y encadenado al fuego

que una vez ya nos fue arrebatado.

Verónica Zondek was born in Santiago de Chile in 1953. She has a History of Art degree from The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and has published a dozen poetry collections and an anthology of Chilean poetry, Cartas al azar (1989). She is a writer of diverse interests, having compiled a major study of the Chilean poet, Gabriela Mistral, and a children’s book: La mission de Katalia (2002). She is a member of the editorial committee for the independent publishing house LOM Ediciones in Santiago, and has translated many poets from English – most recently, Anne Carson.

Poems for staying at home (Day 6)

Laura Wittner

Today we have one of my favourite lockdown poems, ‘Plastic Moon’ by the Argentine poet Laura Wittner. As a special bonus we have a guest reader, the American poet and translator Curtis Bauer, who performs from the garden of his home in Lubbock, Texas, undeterred by either the abundant birdsong or his own wild hair. Thank you, Curtis! The poem appears in The Other Tiger: Recent Poetry from Latin America.

Click for the video poem: https://videopress.com/v/rzV1gNFW

Plastic moon

We are in a dark living room

where I want everything except what I have.

Without shoes, on the floor, drinking wine

from crystal glasses, they put on loud music

and I ask myself: why do we

never play this music?

The possibility of pleasure is lifting me off the ground

and the impossibility of pleasure is making me dizzy.

I lean out of the window to take in some air,

but there’s no more here, only the tight alignment

of back patios and fire escapes,

the absence of sound sarcastically shaken

by the magical music, a darkness of the city’s suburbs

barely known. That’s why I need to go out on the street.

I put on my shoes, leave,

under the muddy light that the chequered floor sucks in like a sponge,

and in the meantime I think, I think.

Why do we never play this music?

I stop on the frozen pavement. There are no smells.

I can’t make out the window

from which I have come. A group of men in the shadows

makes me afraid again. Oh, but thanks.

(Translated by Richard Gwyn)

Luna de plástico

Estamos en un living oscuro

donde quiero todo menos lo que tengo.

Sin zapatos, en el piso, tomando vino

en vasos de cristal, ponen música fuerte

y me pregunto: ¿por qué nosotros nunca

ponemos esta música?

La posibilidad del placer me está haciendo levitar

y la imposibilidad del placer me marea.

Voy a asomarme a la ventana a tomar aire,

pero no hay más, aquí, que la estrecha confluencia

de patios traseros y escaleras para incendio,

la ausencia de sonido mordazmente agitada

por la música mágica, una oscuridad de afueras de la ciudad

apenas conocida. Así que necesito ir a la calle.

Me pongo los zapatos, salgo,

bajo la luz marrón que el piso a cuadros se chupa como esponja,

y mientras tanto pienso, pienso.

¿Por qué nosotros nunca ponemos esta música?

Me paro en la vereda congelada. No hay olores.

No puedo distinguir la ventana

de donde vengo. Un grupo de hombres en la sombra

me vuelven al temor. Ay, pero, gracias.

Laura Wittner was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina, in 1967. She has published several poetry collections, most recently La Altura (Bajolaluna, 2016). She is also a translator from English, and has published work by Leonard Cohen, David Markson, Anne Tyler and James Schuyler. She coordinates poetry and translation workshops and runs a poetry blog in Spanish at http://selodicononlofaccio.blogspot.com/ and she can also be found (in English) at https://intranslation.brooklynrail.org/spanish/inside-the-house/.

Poems for staying at home (Day 5)

Our house today is ‘The House in Tigre’, by Daniel Samoilovich. Tigre is a small town on the Paraná river, which, on its passage towards the ocean, is broken up by hundreds of small, wooded islands, many of them inhabited. The whole, vast area is a web of small estuaries, and the graveyard of three centuries’ worth of shipwrecks and abandoned dreams. As late as the 1870s the delta was the haunt of pirates, some of them women, including the famous Marica Rivera, who, with her band of bloodthirsty followers robbed and murdered travellers, although she also acquired the status of a kind of Robin Hood figure, occasionally distributing her booty among the needy. The people who live on these islands have a reputation for a kind of wistful lethargy, a condition known locally as ‘mal del sauce’ or ‘weeping willow sickness.’ I imagine it as the sort of listless melancholy that afflicts a person who spends too many hours gazing at the slow passage of water.

The House in Tigre

We have a house in South America.

Here are the dogs with no owner,

the river, palm trees, summer,

the little tangled bush

of wild roses,

slanting light in autumn.

Here’s where old clothes end up,

silence, non-matching glasses,

the most long-lived members

of different races, made siblings

by chance, by an oversight of death.

(Translated by Richard Gwyn)

La Casa del Tigre

Tenemos una casa en Sudamérica.

Aquí están los perros sin dueño,

el río, las palmeras, el verano,

el arbolito enmarañado

de las rosas silvestres,

las luces diagonales en otoño.

Acá vino a parar la ropa vieja, el silencio,

los vasos desparejos,

los miembros más longevos

de razas diferentes, hermanados

por el azar, por un descuido de la muerte.

Daniel Samoilovich was born in Buenos Aires in 1949. He has published a dozen collections of poetry since his first, Párpado, in 1973. A bilingual collection of his poetry has appeared in English, translated by Andrew Graham Yooll (Nottingham: Shoestring Press, 2007) and his Collected Poems, Rusia es el tema was published by Bajolaluna in 2014. He is a translator from Latin, Italian, English and French. He has translated, amongst others, the Latin poet Horace and Shakespeare’s Henry IV. Between 1986 and 2012 he directed the Buenos Aires cultural newspaper Diario de Poesía. Three of Samoilovich’s poems can be found in The Other Tiger.

Poems for staying at home (Day 4)

Today’s poem on the ‘house’ theme comes from Rómulo Bustos Aguirre, whose inventive and gently humorous poetry is among my favourite of any being written today. I think of Rómulo as an exponent of ‘slow’ poetry, his characters moving with hallucinogenic grace against the backdrop of his native Caribbean, drinking the ‘red plum wine that stretches memories’, observed by guardian creatures who ‘send passers-by to sleep just by looking at them’. Four of his poems appear in English translation in The Other Tiger, and will shortly appear in PN Review.

Ballad of the House

You will find a house with a strange name

that you will attempt in vain to decipher

and walls the colour of good dreams

but you will not see that colour

nor will you drink the red plum wine

that stretches memories

On the gate

sits a child with a half-open book

Ask him the way to the big trees

whose fruits are guarded by an animal

that sends passers-by to sleep just by looking at them

And he will answer while conversing

with a green-winged angel

(as if it were another child playing at being an angel

with wide banana leaves stuck to his back)

barely moving his lips in a gentle spell

“The cockerel’s song isn’t blue but a sleepy pink

like the first light of day”

And you will not understand. Nevertheless

you will find an immense hallway

where hangs the portrait of a lord,

shimmering slightly, his heart in his hand

and at the back, right at the back

the soul of the house seated in a rocking chair, singing

but you will not heed her

Because in that instant

a distant sound shall crease the horizon

and the child will have finished the last page

(Translated by Richard Gwyn)

Balada de la casa

Hallarás una casa con un nombre extraño

que intentarás descifrar en vano

y muros del color de los buenos sueños

pero tú no verás ese color

tampoco beberás el vino rojo de los ciruelos

que ensancha los recuerdos

En la verja

un niño con un libro entreabierto

Pregúntale por el camino de los grandes árboles

cuyos frutos guarda un animal

que adormece a los andantes con sólo mirarlos

Y él contestará mientras conversa

con un ángel de alas verdes

(como si fuera otro niño que juega al ángel

y se hubiera colocado anchas hojas de plátano a la espalda)

moviendo apenas los labios en un leve conjuro

“El canto del gallo no es azul sino de un rosa dormido

como el primer claro del día”

Y tú no entenderás. Y sin embargo

hallarás un zaguán que yo recorrí inmenso

donde cuelga el retrato de un señor que resplandece

levemente, con el corazón en la mano

y al fondo, muy al fondo

el alma de la casa sentada en una mecedora, cantando

pero tú no la escucharás

Pues, en ese instante

un sonido lejano ajará el horizonte

y el niño habrá pasado la última de las páginas

Rómulo Bustos Aguirre was born in 1954 in Santa Catalina de Alejandría, Colombia. His poetry is inspired by the landscape and characters of his native Caribbean. A professor of literature at the University of Cartagena, he won the Blas de Otero Prize from the Universidad Complutense de Madrid in 2010 and was awarded Colombia’s National Poetry Prize in 2019.

Poems for staying at home (Day 3)

Today’s poem for staying at home is ‘Time of Crisis’, by the Mexican poet Fabio Morábito. Morabito’s poetry, infused with a wry and occasionally coruscating humour, is especially suited to the weird times we live in. This translation, along with the Spanish original, can be found in The Other Tiger: Recent Poetry from Latin America.

If your device allows you access to Instagram, you can listen to Idoia Elola reading the poem in Spanish and English by following the link below:

https://www.instagram.com/tv/B_fuimWB5f2/?igshid=hvvb3bbjlvgb

Time of Crisis

This building

has hollow bricks,

you get to know everything

about the others,

learn to distinguish

the voices and the couplings.

Some learn to pretend

that they are happy,

others that they are deep.

At times a kiss

from the upper floors

gets lost in the lower

apartments,

you have to go down and fetch it:

“My kiss please,

if you would be so kind.”

“I kept it wrapped in a newspaper.”

A building has

its golden age,

the years and fatigue

wear it thin,

so that it resembles

the life that passes by.

The architecture loses weight

and habit gains ground,

propriety gains ground.

The hierarchy of the walls

dissolves,

the roof, the floor, everything

turns concave,

this is when the young people flee,

travel the world.

They want to live

in virgin buildings,

they want a roof for a roof

and walls for walls,

they don’t want

another kind of space.

This building doesn’t satisfy

anyone,

it is in its time of crisis,

to knock it down you’d have

to knock it down right now,

later it’s going to be difficult.

Translated by Richard Gwyn

Época de Crisis

Este edificio tiene

los ladrillos huecos,

se llega a saber todo

de los otros,

se aprende a distinguir

las voces y los coitos.

Unos aprenden a fingir

que son felices,

otros que son profundos.

A veces algún beso

de los pisos altos

se pierde en los departamentos

inferiores,

hay que bajar a recogerlo:

“Mi beso, por favor,

si es tan amable.”

“Se lo guardé en papel periódico.”

Un edificio tiene

su época de oro,

los años y el desgaste

lo adelgazan,

le dan un parecido

con la vida que transcurre.

La arquitectura pierde peso

y gana la costumbre,

gana el decoro.

La jerarquía de las paredes

se disuelve,

el techo, el piso, todo

se hace cóncavo,

es cuando huyen los jóvenes,

le dan vuelta al mundo.

Quieren vivir en edificios

vírgenes,

quieren por techo el techo

y por paredes las paredes,

no quieren otra índole

de espacio.

Este edificio no contenta

a nadie,

está en su época de crisis,

de derrumbarlo habría

que derrumbarlo ahora,

después va a ser difícil.

From De lunes todo el año, 1992

Fabio Morábito was born in Alexandria in 1955 and has lived in Mexico City since the age of fifteen. His award-winning poetry, short stories and essays have established him as one of Mexico’s best-known writers over the past 25 years. He is also a translator from Italian. Much of his work has appeared in translation, to growing international acclaim.

Poems for staying at home (Day 2)

Jorge Teillier (1935-1996)

Today’s house poem, by the Chilean Jorge Teillier, concerns a boy looking out of the window of his parent’s home at a winter landscape. It is the melancholy lyricism of this poem that first attracted me; a mix of myth and the mundane, centring on the boy whose imaginative world is allowed free rein while, in the house, his parents hold a party. The poem concludes in an almost mystical tone, suggesting that a defining experience of childhood will mark the boy forever, and that he is, in a sense, predestined on account of it.

Winter Poem

Winter brings white horses that slide on ice.

Fires have been lighted to protect the gardens

from the frost’s white witch.

Inside a white cloud of smoke, the caretaker stirs.

From his kennel, the freezing dog threatens the drifting ice-floe

of the moon.

Tonight the boy will be forgiven for staying up late.

In the house his parents are holding a party.

But he opens the windows

to see the masked horsemen

who await him in the forest

and he knows his destiny

will be to love the modest scent of night’s pathways.

Winter brings hard liquor for machinist and for stoker.

A lost star flickers like a beacon.

Songs of drunken soldiers

returning late to barracks.

In the house the celebrations have begun.

But the boy knows the party is somewhere else

and through the window seeks out the strangers

he’ll spend his whole life trying to find.

(Translated by Richard Gwyn)

Poema del invierno

El invierno trae caballos blancos que resbalan en la helada.

Han encendido fuego para defender los huertos

de la bruja blanca de la helada.

Entre la blanca humareda se agita el cuidador.

El perro entumecido amenaza desde su caseta al témpano flotante

de la luna.

Esta noche al niño se le perdonará que duerma tarde.

En la casa los padres están de fiesta.

Pero él abre las ventanas

para ver a los enmascarados jinetes

que lo esperan en el bosque

y sabe que su destino

será amar el olor humilde de los senderos nocturnos.

El invierno trae aguardiente para el maquinista y el fogonero.

Una estrella perdida tambalea como baliza.

Cantos de soldados ebrios

Que vuelven tarde a sus cuarteles.

En la casa ha empezado la fiesta.

Pero el niño sabe que la fiesta está en otra parte,

y mira por la ventana buscando a los desconocidos

que pasará toda la vida tratando de encontrar.

Jorge Teillier (1935-96) was a Chilean poet, a key figure in the later 20th century literature of a country dominated by great poets such as Mistral, Neruda, Parra, Huidobro, de Rokha and Lihn. Teillier offers a unique, gentle voice, with a profound sense of the lyrical, often associated with simple, everyday – and usually rural – concerns.

Poems for staying at home (Day 1)

As most of us are staying at home far more than we usually do, I thought I might post a series of poems — or rather, translations of poems — regarding houses. Most of these will be from my anthology The Other Tiger (Seren, 2016), but — who knows? — some might be from other places.

Today’s poem is by the Ecuadorian poet Siomara España, and is titled ‘The Empty House’. The translation is followed by the original Spanish.

The Empty House

Invite no one

into our house,

for they will notice

the doors, walls, staircase

and windows,

they will see the moths

in the corners,

the rusty locks,

the blind, ruined lamps.

Don’t bring anyone to our house

for they will only be distressed

by your table,

your bed, the tablecloth,

the furniture, laugh pityingly

at the cups, pretend to

be nostalgic for my name,

make fun, what is more, of our hammock.

Don’t bring anyone to our house any more

for they will write you songs,

excite your soul,

whisper mischievously,

plant a flower at your window.

That’s why – I beg you – you must

not bring people to our house,

for they will turn pink,

greenish, reddish, bluish,

on discovering broken walls

and withered plants.

They will want to sweep out the corners

they will want to open our blinds

and find, tucked away among my books

the depraved excuses they were searching for.

Don’t bring anyone to our house any more,

for they will discover our absurdities,

will carry you off to faraway beaches

tell you tales of shipwrecks,

drag you from our house.

(Translated by Richard Gwyn)

La casa vacía

No invites a nadie

a nuestra casa,

pues repararán en

puertas, paredes, escaleras

y ventanas,

mirarán la polilla en

los rincones,

los cerrojos oxidados,

las lámparas ciegas, arruinadas.

No traigas a nadie a nuestra casa

pues no tendrán más

que angustia de tu mesa,

de tu cama, del mantel,

del mobiliario se reirán

de pena por las tazas, fingirán

nostalgia de mi nombre,

y reirán también de nuestra hamaca.

No traigas más gente a nuestra casa

pues te escribirán canciones,

te entusiasmarán el alma,

te susurrarán traviesos,

sembrarán una flor en tu ventana.

Por eso no debes, te lo ruego,

traer más gente a nuestra casa

pues se pondrán rosados,

verdosos, rojizos o azulados,

al descubrir paredes rotas

las plantas marchitadas.

Querrán barrer en los rincones

querrán abrir nuestras persianas

y encontrarán seguro entre mis libros

las excusas perversas que buscaban.

No traigas más nadie a nuestra casa,

así descubrirán nuestros absurdos

te llevarán lejos a otras playas

te contarán historias de naufragios

te sacarán a rastras de esta casa.

Siomara España was born in Manabí, Ecuador, in 1976. She is a poet and professor at Guayaquil University; cultural editor of the newspaper El Emigrante and departmental editor of the Casa de la Cultura, Guayaquil. Her publications include: Concupiscencia, Alivio demente, De cara al fuego, Contraluz and Jardines en el aire. She has been included in several international anthologies, including Tapestry of the Sun: an anthology of Ecuadorian poetry (San Francisco: Coimbra, 2010).

Ernesto Cardenal (1925-2020): two poems in translation

Ernesto Cardenal died on Sunday, March 1st, Saint David’s Day. Born into a privileged Nicaraguan family, Cardenal resisted tyrants and dictatorships throughout his life. He died bitterly opposed to the Ortega government in Nicaragua, that betrayal of the revolution which he had once fought for, acting as Minister of Culture in the first Sandinista government (1979-87).

The last time Cardenal crossed my thoughts was after reading an interview of sorts in the Spanish Newspaper El País, in April last year, in which he claimed that he was unable even to comment on Nicaraguan politics: ‘No hay libertad para que yo diga algo, estamos en una dictadura.’ ‘I don’t have the liberty to say anything, we are in a dictatorship’.

The interviewer then asks Cardenal: What, for you, in the current state of affairs, is a revolution? To which he replies, unobligingly: ‘Why are you asking me? Go look in a dictionary. I’ve already written about it in The Lost Revolution. Why repeat things, I have nothing to say, I don’t want to . . ‘

I met Cardenal a couple of times, in Nicaragua, and translated a few of his poems for the magazine Poetry Wales. He was a man who didn’t seem to much care for all the attention he received. He was mentored by the English mystic Thomas Merton as a young man, in the Trappist Abbey of Gethsemani, Kentucky, and he might well have preferred the quiet life of the literary monk to that of the famous revolutionary priest that he became.

One of the poems I translated for Poetry Wales is available on Ricardo Blanco’s Blog here. I translated the following two poems a decade ago, but haven’t published them before now.

LIKE EMPTY BEER CANS

My days have been like empty beer cans

and stubbed-out cigarette ends.

My life has passed me by like the figures who appear

and disappear on a television screen.

Like cars passing by at speed along the roads

with girls laughing and music from the radio . . .

And beauty was as transient as the models of those cars

and the fleeting hits that blasted from the radios

and were forgotten.

And nothing is left of those days,

nothing, besides the empty cans and stubbed-out dog-ends,

smiles on washed-out photos, torn coupons,

and the sawdust with which, at dawn,

they swept out the bars.

OUR POEMS

Our poems still cannot

be published

they circulate from hand to hand

as manuscripts

or photocopies for a day

the name of the dictator

against whom they were written

will be forgotten

and they will continue to be read.

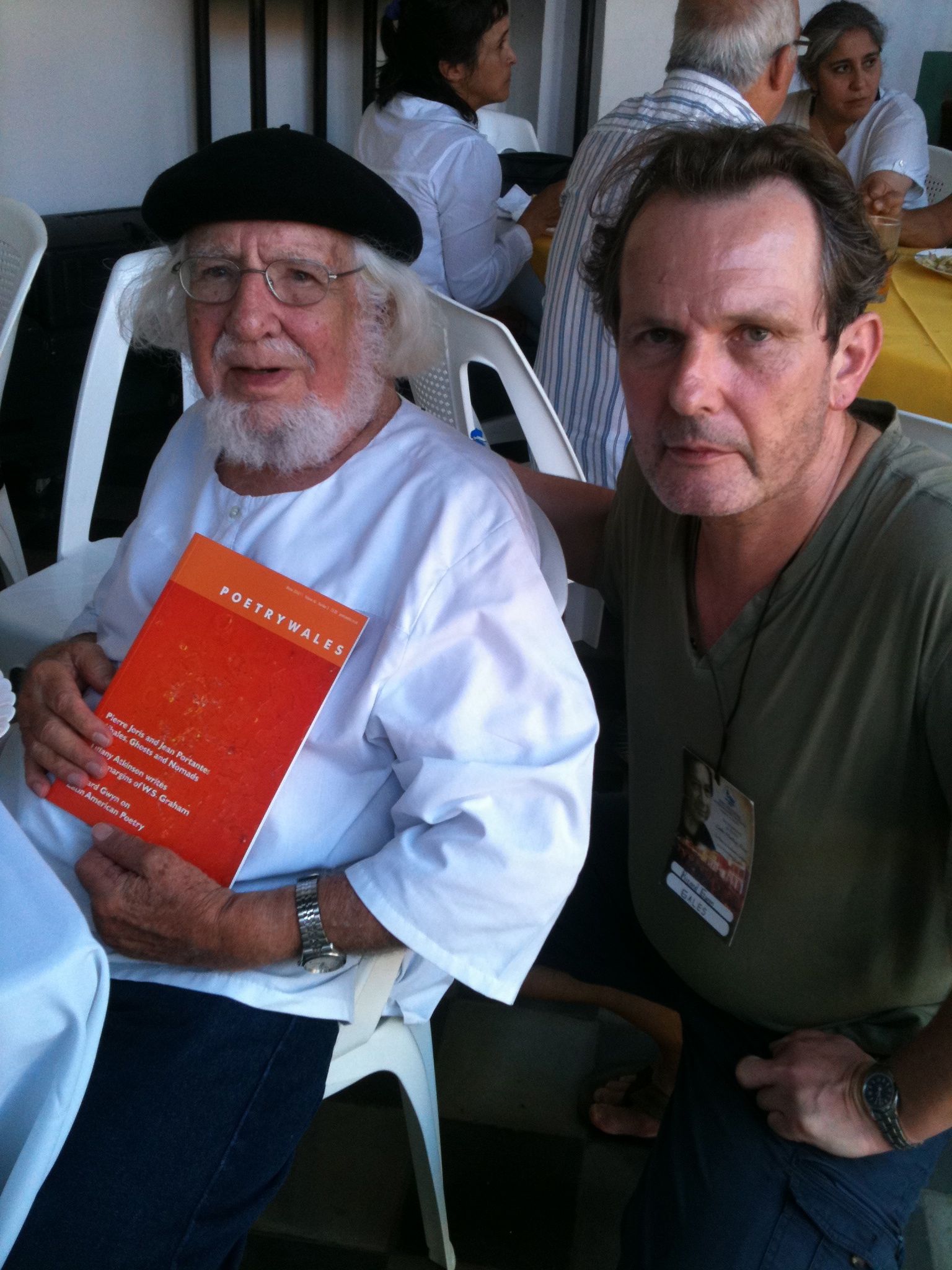

Ernesto Cardenal with Blanco. Granada, Nicaragua, February 2012.

Oaxaca

What does Oaxaca hold in store for me? According to Mesoamerican tradition, which pays homage to Ometeotl, God of Duality, paradise has already been granted to the human race, but to accede to it personal effort is required. Sometimes, one is already predisposed towards duality: this sense of doubleness, or having always had another, an other, a doppelganger of sorts, is described by countless writers; to give just one example, Orhan Pamuk, who wrote in Istanbul of his certainty, while growing up, that another identical Orhan lived behind the closed door of one of the houses that he passed on visits to relatives in another part of the city. Do I share this conviction? I think not. However, I feel a compulsion to discover places like Oaxaca, because I like hearing that paradise has already been granted us, and only a little effort is required in order to dwell in it.

A thousand spiders

It was not that I knew her particularly well, but she knew my wife, and found it opportune to tell me, or wanted to tell someone, which is more or less the same thing, but maybe not. In any case, we were sitting at adjacent tables in the university coffee shop, and it would have been awkward to ignore each other, so she brought her cup and herself over to my table, and told me, almost without introduction, following some fatuous remark of mine concerning recent meteorological developments, that in the warm weather spiders congregate on the balcony of her flat, which was in Cardiff Bay, one of those converted warehouses on the old quays. Every morning, when she went out on this balcony of hers, there would be more spiders, she said, covering all the available surfaces, creeping down the wall, across the white table that she used to sit at for her morning coffee (here she taps her coffee cup with the teaspoon, as though reminding me what coffee is). And why, she wonders, do they pick her flat, her balcony? She speaks with the neighbours on both sides, and neither of them has any trouble with spiders, let alone mass invasions over the summer months. She leans closer: I can sense a revelation coming. My husband, she confides, is arachnophobic. Terrified of them, he is. Bring him out in a cold sweat. Spiders, she repeats, in case I’ve missed something. He’s phobic, like. And they know. The little bastards know. That’s why they come; word gets round, it’s like with cats, she says, you must have noticed how they pay more attention to someone who doesn’t like them; any sign of aversion to cats and they’re all over you. Well, she says, it’s the same thing with spiders and my husband. They can sense his fear. It brings them running from all over. They want to get in. They want to show him a thing or two about fear. A thousand spiders, crawling everywhere. What wouldn’t I do, she says, leaning close again, her voice raspy, fingers clenching the teaspoon, what wouldn’t I do to let them in?

Originally published in Wales Arts Review, 29.06.2016.

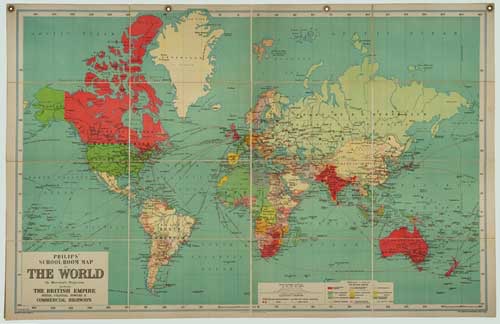

A Greek taverna filled with maps

What is a map, other than the unfolding and laying out of the territory — more accurately, a representation of the territory — through which a person may wish to travel? Rather than indicating merely a physical space or geography, maps always seemed to me to offer a way of thinking, a blueprint for what might happen. Maps spoke of the unknown regions of the mind, of alterity and doomed voyages, of treasure that lay hidden away in creased parchment. Robert Louis Stevenson, in writing of the origins of his Treasure Island, encourages the reader to ‘admire the finger of predestination’ and, after offering that curious directive, continues:

I made the map of an island; it was elaborately and (I thought) beautifully coloured; the shape of it took my fancy beyond expression; it contained harbours that pleased me like sonnets; and with the unconsciousness of the predestined, I ticketed my performance “Treasure Island.” I am told there are people who do not care for maps, and find it hard to believe . . . [A]s I pored upon my map of “Treasure Island,” the future characters of the book began to appear there visibly among imaginary woods; and their brown faces and bright weapons peeped out upon me from unexpected quarters, as they passed to and fro, fighting, and hunting treasure, on these few square inches of a flat projection. The next thing I knew, I had some paper before me and was writing out a list of chapters.

If such potential can be released through the making and contemplation of a simple map, hand-drawn and painted with ‘a shilling box of water colours’, how much unresolved wanderlust might be encompassed by an entire room, hall, or Greek taverna, filled with maps?

In Crete, the Lyrakia bar, which lay toward the eastern end of Hania’s old harbour, near the Venetian boat yards, was owned by Giorgos, who wore dark glasses because – as I was told – he had once accidentally or inadvertently caused someone’s death with his evil eye, and never wanted to be held responsible for such a thing again. The Lyrakia, now long gone, was large and square in shape, and the acoustics were, by chance rather than design, exceptionally good. Across the room, facing the long bar, the musicians would sit and play, usually just two of them, a Cretan lyra and an accompanying lauto or lute, often strummed by Giorgos himself, and in between lay a space for dancing which, as the evening progressed, would turn into a long, straggling affair, as drinkers pitched in and dancers snaked around the floor, the more accomplished taking turns to leap, often with astonishing grace, suspended — or so it seemed to me, though in reality it could barely have been for a second – in another dimension, during which their leaping was freeze-framed for eternity, returning as the explicit record, the recurring image, that my memory now associates with the name lyrakia, from the name of that instrument, the lyre; hence lyric, lyrical, etc., but not its homonym, liar, which is a pity, bearing in mind the logical paradox attributed to Epimenides the Cretan, who said that all Cretans were liars, but being a Cretan himself could not reliably be believed.

When temperatures and emotions were raised, fights occasionally erupted in the Lyrakia with the chaotic zeal of a saloon brawl in an old Western. Chairs became weapons and fists flew, and anyone unfortunate enough to be in the way was forced either to participate, or flee. But whatever the outcome of an evening spent drinking at the Lyrakia, whether it ended in dance or a free-for-all, I often felt as though I had entered a kind of dream warehouse, an emporium of almost infinite possibility, and for one reason in particular: the walls, stained, where visible, by decades of cigarette smoke, were plastered with maps, ancient and modern; maps left by bona fide tourists who had lost their way and ended up unaccountably at the Lyrakia (what could they have made of such a place?); stray hippies, equally adrift, navigating their way back from Afghanistan or India in a hashish stupor; Greek naval ratings (this was back in the day of mandatory three-year military service) readying themselves with ouzo before swaggering to the red-light district of the Splanzia, where I also lived. There were naval maps, charting sea channels (one, I recall, of the entrance to the River Plate) and German army maps from World War Two, decorated in Gothic script, and wholly ridiculous Greek maps, possibly designed to mislead the German occupiers, who, however, were seldom misled; maps in Latin script, Cyrillic script, Chinese, Arabic and Persian. Reproductions of the Catalan maps of Abraham and Jehuda Cresques, the Genoese World Map of 1457; Maps of Empire and of the end of Empire, Soviet maps and even, I noted, maps of the moon and of Mars. I once peered at a map of Europe designed for children, a different colour assigned to every country, and I traced with a finger the name for my own country: OYAΛIA. The unfamiliar lettering lent an alien aspect to the place, transforming it into somewhere foreign, which is strangely appropriate, since ‘Wales’ derives from the Anglo-Saxon word for foreigner. I am a foreigner by default.

In his book, Maps of the Imagination, Peter Turchi claims that ‘The first lie of a map—also the first lie of fiction—is that it is the truth.’ He goes on to consider the Mercator projection, through which the world was represented for four hundred years, and which most of us above a certain age instantly recognise, as it was the standard representation of the world used in classrooms across the world it depicted. ‘Despite its being used for centuries to teach schoolchildren geography,’ writes Turchi, ‘it is a particularly misleading projection for that purpose.’

Gerardus Mercator, a German globemaker, devised his map in 1569, as a New and Improved Description of the Lands of the World, Adapted and Intended for the Use of Navigators. ’On Mercator’s map’, Turchi writes, ‘distortion increases as one moves farther from the equator (and the most important sailing routes of the sixteenth century) so that Greenland appears to be the size of South America—though in fact South America is nine times larger.’ Thus our view of the world changes according to the design or projection of the map we are looking at. There are, apparently, well over a hundred distinct cartographic projections in use today and each of them tells a slightly different story. In his radical deconstruction of the map, J.B. Harley questions the very basis of progress in the cartographer’s craft, as though, through the application of science, reality might be reproduced ever more effectively. Quite apart from the redundancy of progress as a guiding principle (in map making, as elsewhere) is that any representation of territory is somehow neutral: ‘Much of the power of the map’, Harley writes, ‘ . . . is that it operates behind a mask of a seemingly neutral science. It hides and denies its social dimensions at the same time as it legitimates.’ How strange that the representation of ‘reality’ — the earth we walk upon — should be subject to so many interpretations, so many versions; that ‘accuracy’ should be such a slippery concern.

The island of Crete, which has been mapped, with varying degrees of accuracy, since antiquity, is instantly recognizable, being long and thin, its span from east to west far exceeding its width from north to south. However, one of the earliest extant maps from the time of Venetian rule, by Cristoforo Buondelmonti (1420) displays the island standing on its head, as it were, which, since we are accustomed to representations of the island viewed horizontally from east to west – is at once disarming and strange, bringing to mind the form of Corsica, rather than Crete.

We might reasonably assume that a map is a means to an end, the end being an actual place we need to go. But another scholarly cartographer, Denis Wood, in his seminal study, The Power of Maps, writes that maps offer ‘a reality that exceeds our vision, our reach, the span of our days, a reality we achieve no other way. We are always mapping the invisible or the unattainable . . . the future or the past.’ Here, it would seem, the reader of maps is moving beyond the normal terrain of cartography, into the realm of the imagination and of dreams; in other words, into the realm of the writer. And that is precisely what the mapped walls (or the walls covered in maps) of the Lyrakia offered me: stuff to dream with, the raw materials of the writer.

It was in Crete that I first read Borges, another lover of maps, whose story ‘On Exactitude in Science’ I reproduce here in its entirety:

In that Empire, the Art of Cartography attained such Perfection that the map of a single Province occupied the entirety of a City, and the map of the Empire, the entirety of a Province. In time, those Unconscionable Maps no longer satisfied, and the Cartographers Guilds struck a Map of the Empire whose size was that of the Empire, and which coincided point for point with it. The following Generations, who were not so fond of the Study of Cartography as their Forebears had been, saw that that vast Map was Useless, and not without some Pitilessness was it, that they delivered it up to the Inclemencies of Sun and Winters. In the Deserts of the West, still today, there are Tattered Ruins of that Map, inhabited by Animals and Beggars; in all the Land there is no other Relic of the Disciplines of Geography.

Borges attributes these words to one Suárez Miranda, in his ‘Viajes de varones prudentes. The idea that those ‘Tattered Ruins’ of the map, ‘inhabited by Animals and Beggars’ are, indeed, the very fabric of the world we live in, and that the map has become the thing it was designed to represent, is a variation on the theme that obsessed Borges throughout his life, that of the other, the double, most famously expressed in his story ‘Borges and I’. In that piece – again a single paragraph – Borges reflects upon his dual identity as both a first person ‘I’ and as another, his own doppelgänger, a ‘name on a list of professors or in some biographical dictionary’, and acknowledges that little by little, he is giving over everything to this ever-present other. This pervasive sense of doubleness, of wandering through a labyrinth of mirrors, seems curiously apt in relation both to maps (which replicate a version of the world) and translation (which replicates a version of the word).

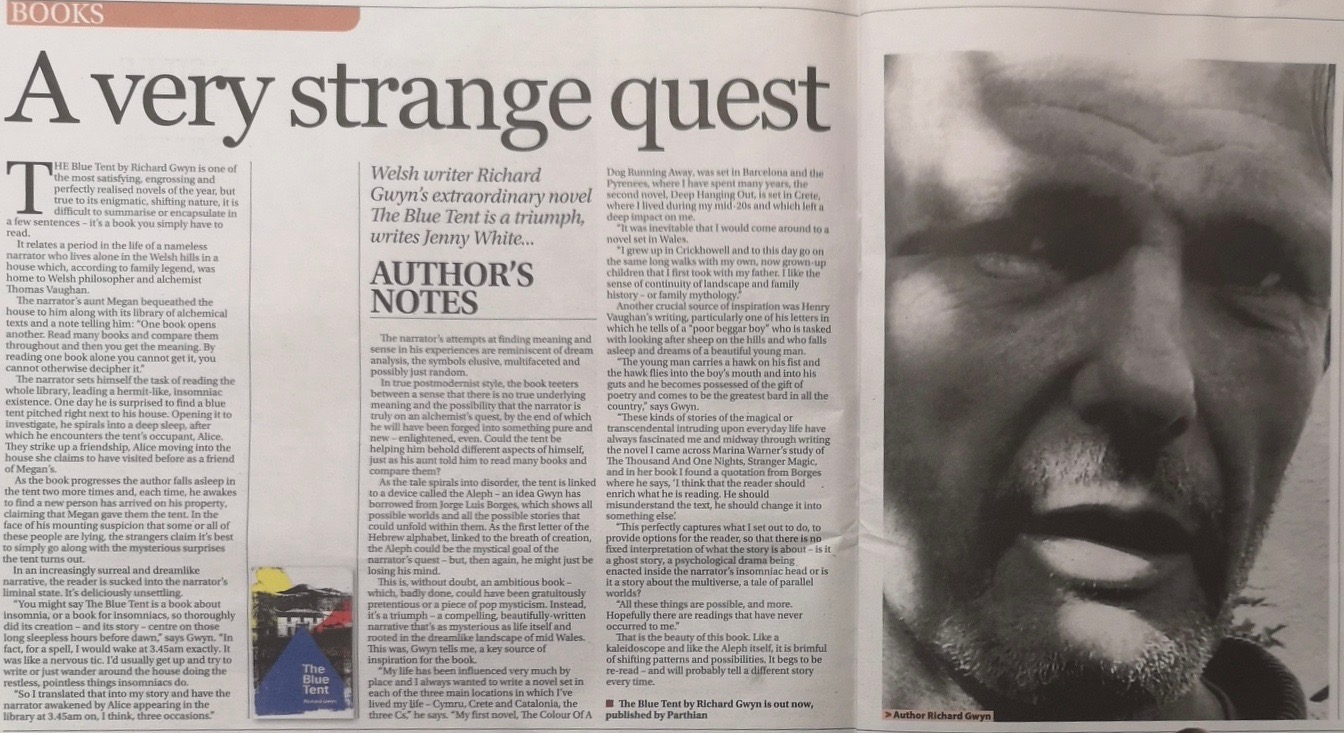

Alchemy, alephs and insomnia: origins of The Blue Tent

The Blue Tent is released by Parthian as an e-book next Tuesday (20th August). Since the novel has provoked quite a few questions from readers, I thought it might be helpful to publish the text of an email interview given to Jenny White, who incorporated some of my rather lengthy responses into her review article in the Western Mail on 13 July.

Reviews of the novel are also available at Nation Cymru and Wales Arts Review.

JW: What inspired this book?

RG: I grew up in Crickhowell and to this day go on the same long walks with my own, now grown-up children that I first took with my father. I like the sense of continuity of landscape and family history – or family mythology. So the landscape of the Black Mountains was an inspiration, but reading Henry Vaughan was crucial. In one of Vaughan’s letters he tells of a lad, a ‘poor beggar boy’ who is tasked with looking after sheep on the hills, and who falls asleep and dreams of a beautiful young man. The young man carries a hawk on his fist, and the hawk flies into the boy’s mouth and into his guts, and he becomes possessed of the gift of poetry and comes to be the greatest bard in all the country. These kinds of stories of the magical or transcendental intruding upon everyday life have always fascinated me, and mid-way through writing the novel I came across Marina Warner’s study of The Thousand and One Nights, Stranger Magic, and in her book I found a quotation from Borges where he says “I think that the reader should enrich what he is reading. He should misunderstand the text; he should change it into something else.” This perfectly captures what I set out to do, to provide options for the reader, so that there is no fixed interpretation of what the story is about: is it a ghost story, a psychological drama being enacted inside the narrator’s insomniac head, or is it a story about the multiverse, a tale of parallel worlds? All these things are possible, and more; hopefully there are readings that have never occurred to me.

I knew that Henry Vaughan’s twin brother Thomas was one of the leading alchemists of his day. He was a priest at the little church in Llansantffraed near Talybont-on -Usk, only a few miles from Crickhowell, between about 1644 and 1650, before losing his parish because he was on the wrong side during the English Civil War. He died in mysterious circumstances in 1666, probably by setting fire to mercury and inhaling the fumes, but there were rumours that he hadn’t died, that he had in fact been a spy for the Royalist cause, and even that he faked his own death and reappeared in Amsterdam, where he continued to produce alchemical texts, but in Latin, rather than English. However, his brother, Henry, records in a letter to one John Aubrey that Thomas died “upon an employment for His Majesty.” Whatever happened, there is no record of Thomas Vaughan’s death and burial in Aylesbury, where he lived during those last years. Then, in one of those twists you couldn’t make up, I discovered that the people who ran the local chemist’s shop in Crickhowell when I was growing up, and had known all my life only by the husband’s surname, were Vaughans on the maternal side, descended from the same historical family as Henry and Thomas, and again I got that sense of connection and continuity, of the past haunting the present, which is another of those threads embedded in the story.

Finally, of course there is Borges: in his short story ‘The Aleph’, the narrator comes across a portal, or small magical device, on which he can ‘read’ not only the world around him, but all possible worlds, across time and space. The aleph is the final piece of the puzzle. Or the first, perhaps, Aleph being the first letter of the alphabet in Hebrew, Arabic, Aramaic and other ancient languages; as such it is a portal to language, and therefore to self-expression. I borrowed the concept of the aleph directly from Borges, but strangely, as one reader pointed out, having downloaded my book onto the kindle app on his phone, it occurred to him that he was reading a story about an aleph, on an aleph. The mobile phone is a kind of aleph for the 21st century, in which one can access information on just about anything that has ever happened – up to a point.

The idea of the tent as a vehicle for bringing my characters into play came to me out of the blue, as it were, and prompted me to start with that image, of the blue tent appearing unannounced at the end of the narrator’s garden.

JW: Tell me a bit about the alchemical/mystical texts mentioned in it – how did you choose which ones to include, what sparked your interest in them and how did they drive the plot and undercurrents in the book?

RG: I was reading Jung and Marie-Louise von Franz as background research for the book, and becoming increasingly intrigued by the idea of alchemy as a route towards self-knowledge, which was its original intended goal, not only for Jung and his followers, but also for the ancient and the renaissance alchemists such as Thomas Vaughan and his contemporaries. Renaissance and seventeenth century Britain was abuzz with cranks and visionaries of this kind, John Dee – another Welshman, and astrologer to Queen Elizabeth I – being the most famous. The titles of the obscure alchemical treatises my narrator reads were mostly taken from von Franz, although it might have been tempting to invent one or two of them. The truth is that a lot of those alchemical texts are completely unreadable, and I certainly wasn’t interested in writing pages of exposition about the alchemical process, which in any case I barely understand. And, not unrelatedly, the underlying quest for the Holy Grail, which pervades the Arthurian legends and, especially, the story of Parsifal, or Perceval – yet another Welshman – was certainly present in the background of my own creative process. Interestingly enough, Chrétien de Troyes, the first chronicler of the Arthurian tales, mentions that Parsifal ‘came out of Wales’, and Wales, of course, was seen as a backwater (and many still regard it as one). The implication is: ‘what good could ever come out of Wales?’ And yet Parsifal, as we know, found the Grail, or, in the language of alchemy, the philosopher’s stone, simply by asking the right questions. This is the aspect of alchemy that most intrigues me; to continually be asking questions, and never to accept facile or received explanations.

JW: How would you define or describe the process that the narrator goes through in this book? Is it alchemical? How is he changed by the experience?

RG: The traditional alchemical process involves four stages – allegedly the method for transforming base metals into gold – but this chemical transmutation was only a formula or trope, and the real, secret intention of alchemy was always one of self-discovery. The four stages are called nigredo, or blackening; albedo, or whitening; citrinitas, or yellowing, and rubedo, or reddening. I wanted the narrator to pass through these phases with each visit he makes to the tent, but without being too literal about it. I didn’t want to write a New Age mystical thriller any more than I wanted to get bogged down in the arcane details of alchemy. But I wanted to have some fun along the way, and there are moments when the narrator is well aware of the comic or absurdist potential of his quest, shut away in his aunt’s library with all those unreadable texts. I was, however, keen that the four phases represented by the colours of the process were included on the cover, and the designer, Marc Jennings, did a really fine job, I think.

In order to reflect the alchemical process at work, the narrator has to go through a kind of shift in personality with each phase, but again, I didn’t want to labour this aspect of the story. I don’t know to what extent that was successful. When you live with a book for such a long time, you start going a bit crazy and it’s difficult to get a clear perspective. Which is where the reader comes in. I like very much the idea that different readers will come away from the book with completely distinct responses, a completely different understanding of what they read.

JW: I loved the dream-like, shifting nature of the narrator’s world. What challenges did you face in depicting this? What did you enjoy about depicting this, and about writing the book in general?

RG: The book took me over twelve years to finish, and I abandoned it at least twice, and completed two other books in the meantime. I just couldn’t get the structure right. Originally it was going to be a much bigger novel, with three distinct storylines, one from the point of view of the narrator, another would have been Alice’s story, and a third that comprised extracts from Aunt Megan’s journals. But in the end I cut all the rest away, took away the scaffolding, and was left with only the bare story. It seemed better that way. The dream-like, shifting nature of the story came about naturally enough. Like the narrator, I am a chronic insomniac, and spend much of my life in a similar state of bewilderment at the passage from night to day and back again. I’ve written about this in my book The Vagabond’s Breakfast, where I say that insomniacs dismantle the familiar division of time into identifiable segments, so that night and day form a single seamless trajectory. Since one’s life is a continuum of sleeplessness, snatching rare hours here and there at random times of the day or night, yesterday seeps into tomorrow without allowing today to get a toehold.

And in The Blue Tent I refer to a ‘celebrated insomniac’ – in fact the Romanian-French philosopher E.M. Cioran – who ‘claimed that long periods without sleep amount to a tyranny of consciousness; that normal people, who sleep the prescribed number of hours, awake each day as though starting out on a new life, but that for the insomniac no such renewal can occur. Instead, the sleepless live in a continuum of consciousness, and while everyone else rushes toward the future, we insomniacs remain outside.’

In Marina Benjamin’s recent book, Insomnia, she makes some wonderfully astute observations about the insomniac life, and reflects on the paradox that while the insomniac wants to sleep, craves sleep, would give anything, at times, for some sleep, there is also a resignation – sometimes more than resignation, something approaching acceptance or even desire – to follow the imaginative threads provided by insomnia and use them creatively. This is summarised at the end of her book, when she writes: ‘I want to flip disruption and affliction into opportunity, and punctuate the darkness with stabs of light.’ You might say The Blue Tent is a book about insomnia, or a book for insomniacs, so thoroughly did its creation – and its story – centre on those long sleepless hours before dawn. In fact, for a spell, I would wake at 3.45 exactly. It was like a nervous tick. I’d usually get up and try to write, or just wander around the house doing the restless, pointless things insomniacs do. So I translated that into my story, and have the narrator awakened by Alice appearing in the library at 3.45 on, I think, three occasions.

JW: How does this book compare to previous books you have written? Do you feel you have developed/moved on as a writer in creating this book? If so, tell me a bit about how…

RG: Every book presents a unique challenge, and the motivation behind my three novels to date has been different. I’m talking about fiction here, although my non-fiction shares many of the attributes of the novels and at times it’s difficult for me to discriminate between what actually happened and what I merely imagine having happened.

Nevertheless, my life has been influenced very much by place, and I always wanted to write a novel set in each of the three main locations in which I’ve lived my life: Cymru, Crete and Catalonia. The three C’s. My first novel, The Colour of a Dog Running Away, was set in Barcelona and the Pyrenees, where I have spent many years; the second novel, Deep Hanging Out, is set in Crete, where I lived during my mid-twenties, and which left a deep impact on me. It was inevitable that I would come around to a novel set in Wales. None of my books are concerned with social realism, or what people might consider the concerns of the everyday. In terms of literature and art in general, I don’t like being tied to the literal, or wish to describe people’s marriages or affairs or what it’s like to work in an office or go on holiday to the Maldives. I’m not a big fan of realism, which sometimes seems like the last resort of the desperate; the well-rounded fiction as a celebration of triumphant individualism operating within a neatly decipherable universe. Which doesn’t mean that I don’t care about real, marital, familial, social or political issues; I mean, there’s nothing else, is there? But I’m just not interested in writing about them directly in my fiction.

JW: What writers or other factors have influenced/shaped you as a writer?

RG: Too many to name, but I must mention Jorge Luis Borges, of course, closely followed by Italo Calvino and the Greek poets C.F. Cavafy and Yannis Ritsos. These all helped shape my identity as an aspiring writer, and I wouldn’t be the same person without having read them. I currently read more fiction from places other than the US and the UK, especially from Spain and Latin America, and I read a lot of poetry, in Spanish and French, as well as English. But I am also a translator (from Spanish) – and this is probably the biggest single factor on the way I continue to evolve as a writer. By which I mean my work as a writer and as a translator, although quite separate, are intimately woven together at some subterranean level, and this probably has a huge influence on the way I think about language, and therefore about writing.

Among the English language writers I’ve most enjoyed in recent years – but would not count as influences – are Mavis Gallant, Paul Bowles, Joan Didion, Gay Talese, Geoff Dyer and most recently Rebecca Solnit, Olivia Laing, Maggie Nelson and Sarah Manguso – all, apart from Gallant and Bowles, writers of so-called nonfiction, oddly enough. In recent years almost anything published by Fitzcarraldo. I would say that I’m also influenced by visual artists, notably the German Expressionists and the Surrealists, and film makers like Werner Herzog and David Lynch.

JW: Tell me a bit about yourself, your background, how you became a writer and what drives/motivates you as a writer.

RG: You can read all this in The Vagabond’s Breakfast, which was written at the same time I was working on the first draft of The Blue Tent. I think I’ve probably always been a writer, even during the years when I wasn’t writing. I’m motivated by curiosity, rather than any innate talent or aptitude. I think we become the writers we are by trying to write the books we would like to read. The moment you lose your interior compass, try to be something that you are not, write to follow literary fashion or to gain fame and prestige, you’re probably in trouble as a writer.

JW: What do you hope readers will get out of reading this book?

RG: Like I said when I cited Borges, it would please me if readers were able to enrich my text by intelligently misunderstanding it, and by changing it into something else. That way it would have as many interpretations as there are readers, which is as much as any writer can hope for.