Necrophiliacs of the written word

So what is poetry anyway? A rather perplexing question put about more than strictly necessary at the Sabad World Poetry Festival, which I have been attending in Delhi. On the first day, after a long haul from the airport through the dense traffic, noise, onslaught of colour and intense odour that is India, I arrived at the festival site, hosted by Sahitya Akademi and the Indian Ministry of Culture, and sat in the festival hall listening to a man sing. After he had sung his poem, or his song, they gave him a lovely bunch of yellow flowers. In fact, as I discovered, they give everyone a nice bunch of flowers (mine, on Sunday, were peach roses, which almost went with my shirt). Everyone was in a jolly good mood, what with the abundance of flowers and all. There were poets from all over the world, and especially from the subcontinent. I met up with George Szirtes from the UK, and Moya Cannon and Lorna Shaughnessy from Ireland, both of whom I have met before, and various other poets I have encountered over the past few years at festivals of this kind, including Sudeep Sen and (for the first time) the fine Indian poet Ranjit Hoskoté. There is a dancer on the second night and a sublime group of musicians from Rajasthan on the third. But I am perplexed throughout by the recurring question of ‘what is poetry?’ I mean, who really cares? One rather cool suggestion in the opening speeches (which I missed, en route from the airport) was “witnessing, wandering and wonder”. Another, which I prefer, offered to me by Moya Cannon, in a slightly different context (but which still rings true) was the opportunity to indulge our negative capability. Someone raised the point that a recent article in the Washington Post – which cites a poet who shares Blanco’s name – had pronounced poetry dead, for once and for all. Bravo, I say. That makes us so-called poets the ghouls of literature. Don’t you love that idea? Or am I merely misquoting Don DeLillo, writing of the novel, another allegedly ‘dead’ form? Either way, poet or novelist, we are obviously the necrophiliacs of the written word.

Facts about Things

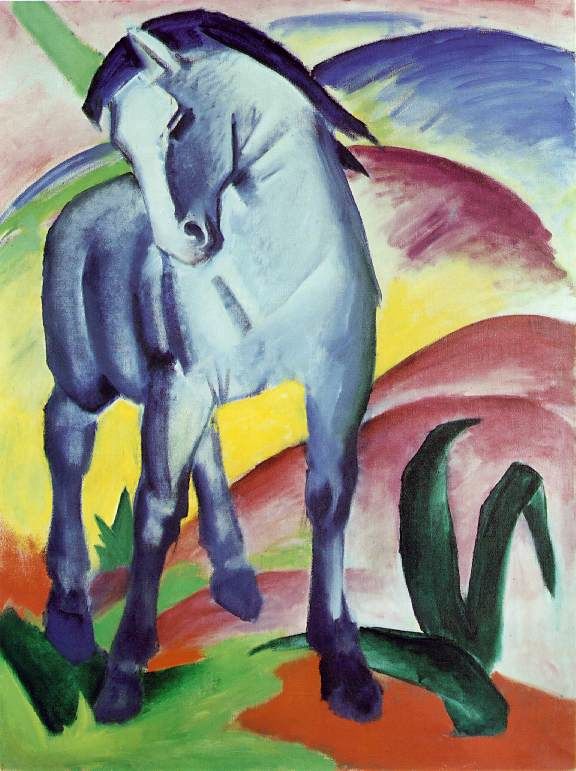

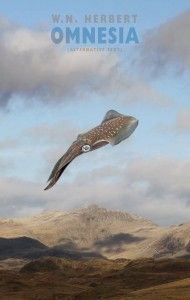

Omnesia, W.N. Herbert’s new collection of poetry, comes in two volumes, subversively titled Alternative Text and Remix, so as to disabuse the reader of any notion of an ‘original’. The word ‘omnesia’ is a conflation of omniscience and amnesia, the latter quality bringing into question the actuality of everything we know – especially, perhaps, our omniscience.

Omnesia, W.N. Herbert’s new collection of poetry, comes in two volumes, subversively titled Alternative Text and Remix, so as to disabuse the reader of any notion of an ‘original’. The word ‘omnesia’ is a conflation of omniscience and amnesia, the latter quality bringing into question the actuality of everything we know – especially, perhaps, our omniscience.

Herbert’s oeuvre is already varied and profuse, and this new collection is expansive in every way. The two volumes mirror and reflect upon each other, so that the airborne squid on the cover of ‘Alternative Text’ is flying towards the reader while the one on ‘Remix’ travels laterally – just as the author in the photo gazes amusedly to the right on the one book, and bemusedly to the left on the other. As an epigraph from Juan Calzadilla, tells us: ‘I have transformed myself into another / and the role is going well for me’. The concept of non-identical twin texts embodies, as the poet reminds us in his Preface, a rejection of ‘or’ in favour of ‘and’. A core of poems appears in both volumes, and the title poem opens ‘Alternative Text’ and closes ‘Remix’. But this sequencing does not signify a preferred reading order. Instead, we are warned off any kind of systemic coherence in the poem’s opening lines: ‘I left my bunnet on a train / Glenmorangie upon the plane, / I dropped my notebook down a drain; /I failed to try or to explain, / I lost my gang but kept your chain – / say, shall these summers come again, / Omnesia?’

Almost anything is a cue to Herbert, setting him off on one of his preferred riffs, especially our inescapable doubleness, exemplified by the two books – themselves containing other books which scurry off at tangents – and the frequent collusion of the narrative ‘I’ with other selves. In ‘Paskha’, the narrator sees a dead scorpion ‘in silhouetted crux’ and is ‘troubled by the brain’s chimeric quoins / its both-at-onceness, how the memory’s / assembled with our present self for parts . . .’ And it is this very both-at-onceness that has me riffling through the pages of ‘Alternative Text’ while reading ‘Remix’, following the demands of a connectivity which the poet’s Preface planted at the outset.

The poems take place in and meditate upon the poet’s journeys from Crete to the north of Britain, from Mongolia to Albania, from Finland to Israel, from Venezuela to Siberia, and among the poet’s several antecedents I was pleased to meet the shadow of Byron, especially in the ‘Pilgrim’ sequence. There is also a fine selection of poems in Scots.

The choice of epigraph usually serves as a pointer towards the poet’s intended direction. We are warned, in a quotation from Patricia Storace, that ‘In Greece, when you hear a story, you must expect to hear its shadow, the simultaneous counterstory.’ And not just in Greece. In ‘News from Hargeisa’, for instance, the counterstory of Somalia’s troubled history lies beneath every line, evoking local parable in the story of a lion, a hyena and a fox (animal imagery predominates in many of Herbert’s poems), as well as in the poet’s mourning of his friend Maxamed Xaasi Dhamac, known as ‘Gaarriye’, the late great Somali poet to whom both volumes are dedicated.

I am sure I missed subtle allusions and even whole thematic directions, and yet still enjoyed the poems I didn’t get. I did wonder how many people – outside of those who have lived on Crete – would ‘get’ ‘The Palikari Scale of Cretan Driving Scales’, a poem in which the driver’s recklessness is measured in direct relation to the magnificence of his moustache.

One might complain that there is simply too much in these books: not in the sense that they are lacking in editorial discretion, but that they demand a readerly imagination as febrile as Herbert’s in order to keep up. Is W.N. Herbert one person? I suspect not: and in any case he seems quite comfortable swapping costumes with his multiple others. I suspect also that Omnesia is a work one needs to live with for a while before appreciating all the shifts and mirrorings, puns and doublings, but even on a first acquaintance it offers richly rewarding reading.

Review published in Poetry Wales, Summer 2013 49 vol 1.

And nearly a year having passed since writing the above review, I can assure you that Omnesia repays revisiting. In so many ways.

Facts about Things

Things are tired.

Things like to lie down.

Things are happiest when,

for no reason, they collapse.

That French plastic bottle, still half-full,

that soft-back book, just leaning on

another book, drowsily:

soon they will want to go outside,

soon you will find them in the grass

with the empty bleaching cans and that part

of an estate agent’s sign

that’s covered in a fine grime like mascara.

That plastic bag you’ve folded up

feels constrained by you and wants

to hang from bushes, looking like a spirit,

sprawled and thumbing a lift.

Things are bums, tramps, transitories:

they prefer it when it’s raining.

Lightbulbs like to lie in that same

long, uncut, casual grass

and watch the funnel effect: the way

on looking up the rain all seems

to bend towards you,

the way the rain seems to like you.

Things which do not decay

like it best in shrubbery, they like

to be partly buried.

They like the coolness of the grass.

Most of all, they like it

when it rains.

Cities and Memories

Variations on a theme by Calvino

When a man drives a long time through wild regions, his imagination begins to wander. No, that’s not right. Try again. When a man drives across the last continent at night, from south to north, he must pass the mountain plateau of Omalos. Oh please, not that. Once more? When a man drives a long time across the dry plains of Thrace, he begins to wonder at the migrations that have marked this wretched zone. Turks, Bulgarians and Greeks, with varieties of cruelty and facial hair, wielding curved swords at one another’s throats for centuries. Forced expulsions, exterminations, and the underlying terror that who you are, or who they say you are, is all a terrible mistake, merely circumstantial. And why, for that matter, are you not someone else? If only – you conjecture – I were someone else, and belonged to a different tribe, had a different shaped moustache or nose, the smallest detail of appearance and accent that matters beyond the value of a life. The Levant’s legacy, never yet resolved: Greek, Turk, Arab, Jew. I want to be friends with everyone, and yet know I must have enemies too, if only in order to maintain my friendships. What kind of crazy thinking is that? Salonika, Smyrna, Alexandria, Beirut. We edge into new territories, in which boundaries are differently conceived and yet still intact. How do we progress from here, to the next point, the next dubious epiphany? I feel at once as though we have been witness to a slow disembowelling, over many centuries.

First published in Poetry Review, Summer 2013.

© Richard Gwyn

Epic poetry and canine aficionados

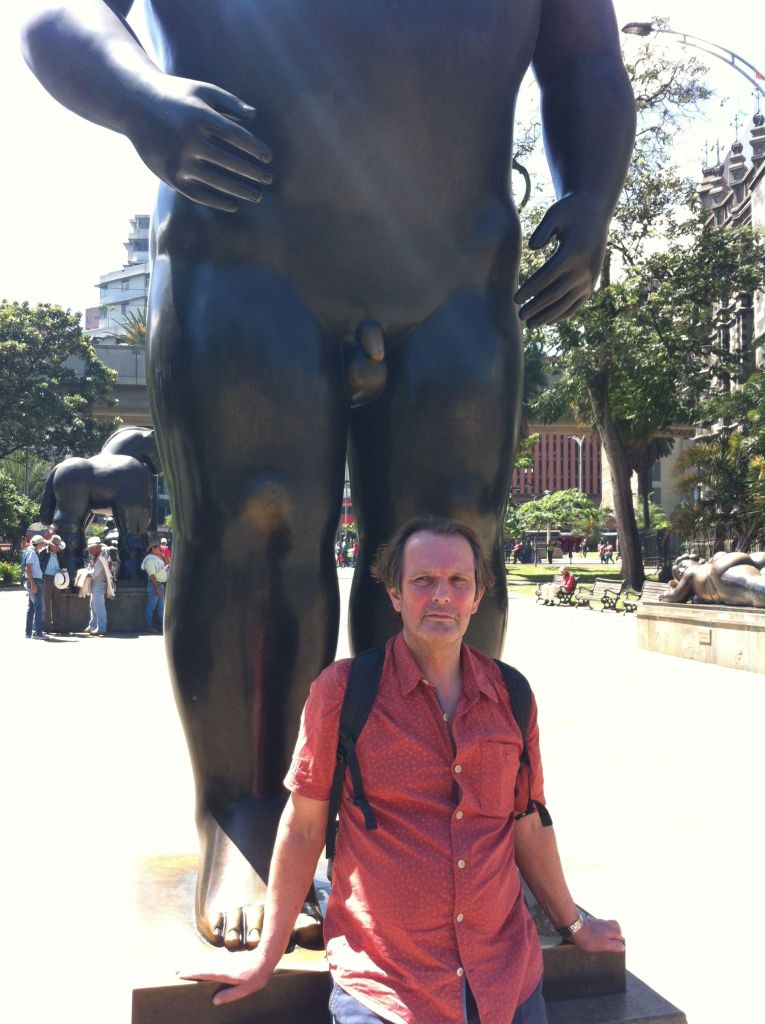

Posting a few pictures as a last offering from my trip to Colombia:

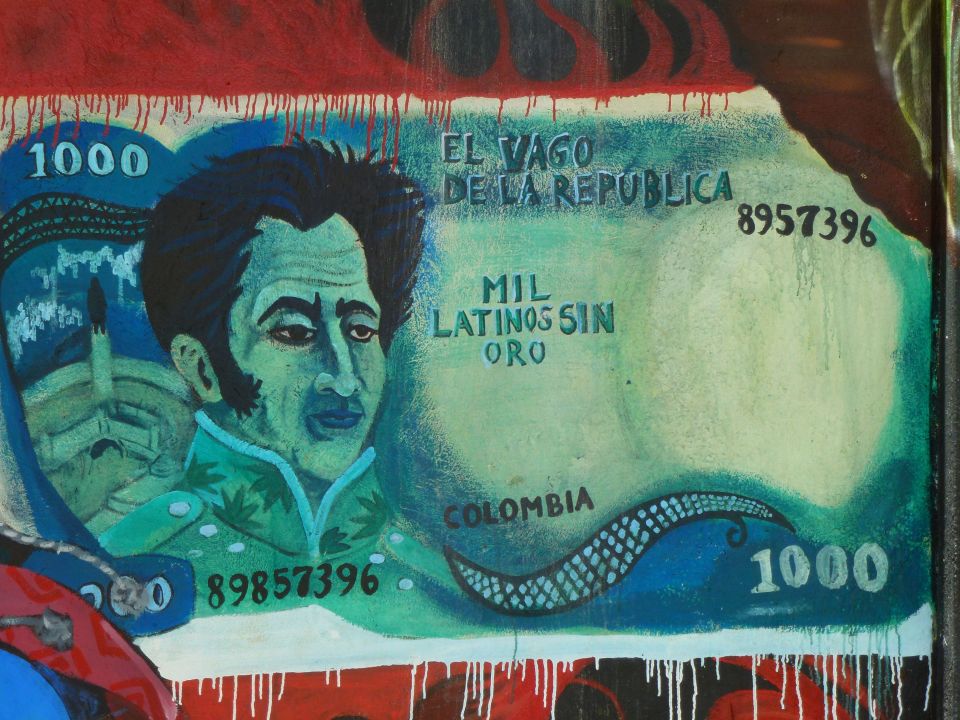

The lettering on the banknote displayed in the wall graffiti suggests that a thousand poor die for each 1000 peso banknote in the idle republic – well, that is one interpretation – and it was displayed in Santo Domingo, once a zone of Medellín riven by incessant gang warfare. Now it is home to a stylish library, designed by the architect Giancarlo Mazzanti and built in 2006-7 with Spanish money (just in time, I guess: there won’t be any more of that coming for a while), which I visited with Jorge and Moya. The people in the library were very friendly and showed us the new theatre. There are lots of places for kids to play intelligent games and read books, but there weren’t actually many kids around, apart from a couple who tried tapping us for money in a playground on the way in.

Below, a solitary canine fan awaits the start of our reading last Saturday morning in the hot and lazy town of Tarso, three hours’ drive from Medellín.

And finally, a photo of the amphitheatre where the main poetry readings took place later the same day. This shot is from the closing recital, where the packed auditorium was composed of over 2,000 listeners of all ages. They sat there in the heat (the readings began at 4 pm) while the poets lurched their way through the marihuana fumes emanating from the audience to read their pomes (sic). I don’t know why, but the applause became louder and louder as the six-hour performance wore on. I’m certain this response had little or no bearing on the quality of the poetry, but it filled my heart with warmth and genuine respect for the Colombian people. After all they’ve been through over the past thirty years, withstanding a poetry recital of such epic proportions surely demands astonishing powers of endurance. I salute them.

I set out on a journey

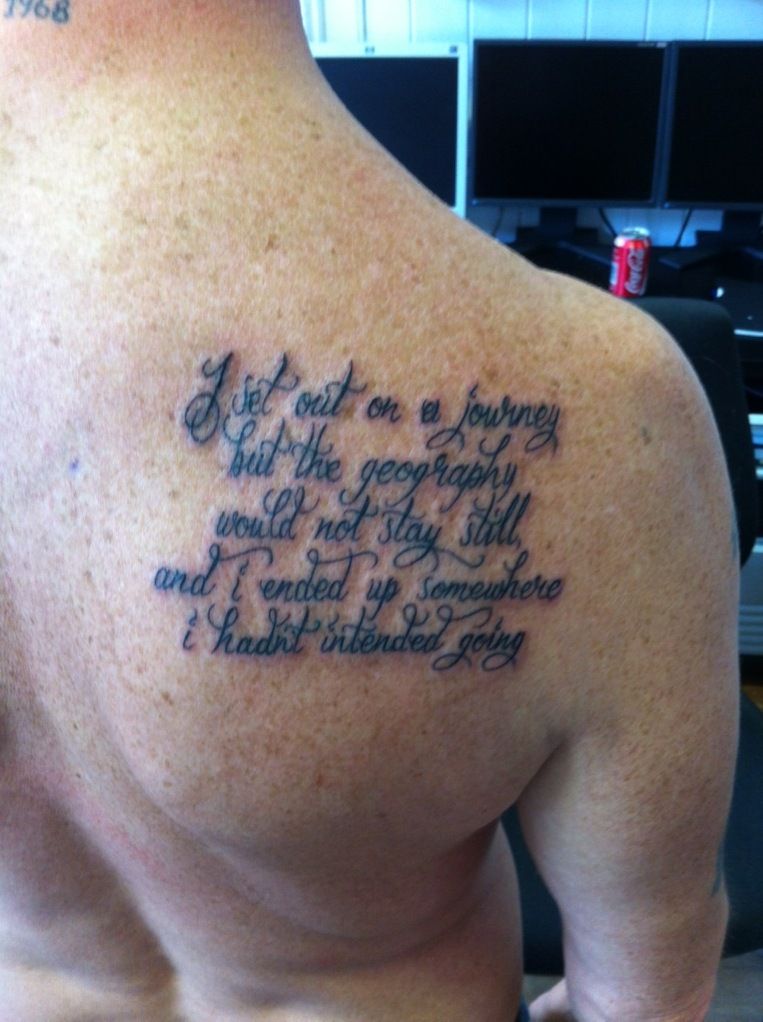

Imagine my surprise (horror/fascination/wonder) on receiving a photo on my iphone a couple of months ago, displaying the shoulder of a regular at The Promised Land (a charming fellow and good acquaintance: I do not know him well enough to claim him as a friend) who had had tattooed upon himself a short poem of mine, in its entirety. The poem is called ‘Restless Geography’, and, in case it is difficult to make out the words in the picture, it goes like this:

I set out on a journey, but the geography would not

stay still, and I ended up somewhere I hadn’t intended

going.

I wanted to use this as the title of a collection of prose poems, but the publishers said it was too long, and I would have to cut it down, which I didn’t want to do. So we called the book Sad Giraffe Café instead.

The night before last, the house having being borrowed by daughters, who were entertaining friends, I put down the book of poems I was reading, and Mrs Blanco and I set off under Scary Bridge, and across the road into the Vue cinema and fitness complex. The long haul up the escalators presented a panorama of the huge gym on the first floor. The place was almost empty, just a few Wednesday night loners pumping iron and a solitary immobile cyclist. All three of them were young men. There was something tragic in this display of righteous pumping and pedalling in the perennial pursuit for a well-toned physique and bulging biceps under the blinding glare of strip-lighting. All I could see, as we glided past them on our upward journey, was a dreadful torpor. All I could see – as Beckett might have said, actually did say – was ashes. This set the tone for the rest of the evening. The chatty girl in the empty ticket hall (a dozen cinemas, no visible customers) told us we were the only people to have bought tickets for Seven Psychopaths, the new film by Martin McDonagh, and starring Colin Farrell, Woody Harrelson, Sam Rockwell, Christopher Walken and Tom Waits (pictured, here, in an empty cinema).

So Mrs Blanco and I chose our seats, two thirds of the way back, next to the aisle, and had the place to ourselves. This is a strange sensation. A private viewing in a full-size cinema. The seats are very comfortable at Vue, and there is plenty of space, but even so it is a luxury to lounge in abandoned fashion, and lounge we did. It is a pleasure to be able to loudly curse the fools who populate the ads and the trailers, as practically every film that Hollywood chucks at places like the Vue franchise are complete tripe. Trivial meaningless drivel circling around a half dozen well-worn and clichéd themes, all of them dire and depressing.

But the empty cinema inspires melancholy, rather than depression. The film is entertaining, even if it adheres to many of the post-modern meta-fictional tropes made fashionable by Tarantino. Nevertheless it made me laugh like a loon, which is never a bad thing. Laughed myself almost into a stupor at various points in the movie, in fact.

We came home around midnight, and the party was breaking up. The young were setting off for Clwb Ifor Bach or some other Cardiff nightspot.

Earlier in the evening, when I had been reading through the Selected Poems of Roger Garfitt, two short lines from his poem ‘The Journey’ had stood out:

I had to go on

without me

And I realised these lines evoked the precise emotion that had (paradoxically) accompanied me earlier that evening, as I passed the young men pumping iron in the empty gym, on our way up the escalator to the empty cinema. I realised also that if I had not been accompanied by Mrs Blanco, my evening would have been unutterably desolate and solitary (in a bad way). Company helps divert us, temporarily, from our essential and terrifying aloneness, allows us to go on, even if ‘without oneself’, who is unaccountably absent, then at least sharing the emptiness with a warm and sentient human partner.

Afterwards, I lay awake, and the words of Garfitt’s poem stayed with me long into the night.

According to . . .

According to

Tiffany Atkinson.

Once, about the time you start to notice trees

and he found out his wife was not his wife

in any sense but name, Elijah took the dog,

two apples from the sideboard, and went out.

Not long afterwards, he came upon an old friend

bent beneath the bonnet of his car, cursing

every sprocket of combustion engines. What

do you suppose the point is? asked Elijah.

And the friend replied, I have to be there.

Throw your spanners down and come with me,

Elijah said. And so the friend did. And his name

was Tomos, after whom he never thought to ask.

And Elijah was amazed. Next there was a daughter

which, close up, they didn’t know. But Tomos said

she looked a lot like his girl would’ve had she lived.

He split one apple threeways, and the girl laughed.

And her laugh was as a pocketful of loose change,

as the moment when you down your pint and dance.

Her name was Manon. She was heading to the clinic.

Then she got her mobile phone out. Mam? she said.

So from there they went north, telling stories. Till

they came upon a farmer, bitter drunk, for all his fields

had failed. They listened, picking fruit seeds from their teeth,

and where those fell sprang cider-presses, booming.

Soon a crowd came out to see what had been happening.

I killed a man, said one man, looking thin. Shit happens,

said Elijah. Sell your house, give all the money to his folks

and walk with us. The man did. He gave nobody his name.

Meanwhile the crowds grew till there wasn’t room

to slide a slice of toast between them. Tomos asked,

what’s this about then? And Elijah said, just as you

left your hurtful car to walk with me, so this lot feel.

Look at the rhododendrons! They don’t give a toss

about the funding cuts, the polar bears. They do

their own thing. Throw your keys into that hedge,

ignore the cameras. Be your own true kicking self.

So Tomos did. He was a simple man, and able

to draw truth like tears from anyone. Elijah said,

you know the way that pressure-regulating valves

secure the rear-brake lines for heavy braking?

Tomos nodded. Well, Elijah said, you see, that’s you.

At this the grief beat out like crows, and Tomos felt

a hatching, in the space, of light. Elijah felt it too. And

where they left a third, unheard-of apple, grew a hamlet,

grew a village, grew a town, where people started over hope

fuller than all the Born Again Virgins of America.

These are the words of Manon, set down with the baby

on her knee. Elijah Tomos, he’ll be. All this happened.

From Catulla, Bloodaxe, 2011. For a review of this book, click here.

Horses

Blanco is somewhat anaemic these days, as a consequence of drug therapy whose other side effects are listed as lethargy, fatigue, depression, anxiety, and . . . rage. That’s right, Le rage. So, to save the venting of my swollen spleen, allow me to regale you instead with a quite uncharacteristically mellow poem from the collection I am currently translating by Joaquín O. Giannuzzi, an Argentinian poet of wonderfully dark and understated talents, which will be published in the autumn by CB Editions.

HORSES

Horses put up with

the weight of history

until the invention of

the internal combustion engine.

Now, whenever they are born

they stumble and tarry before the light

believing they have burst in

on the wrong world.

The Question

THE QUESTION

by Tom Pow

How do people live?

He was standing two in front of me

in W. H. Smith’s and what

he wanted to know was,

How do people live? He asked

the question as if someone

had given it to him as a gift –

his eyes shone with the wonder of it.

How do people live? He looked around

at us all, knowing the question to be

unanswerable, knowing that no one

had an option but to shake their heads

or to look down at their hands,

holding Heat magazine

or the day’s trivia or greeting cards

which laid claim to the most minor

matters concerning how people live.

Yet he must keep on asking the question –

though a couple of girls giggle,

a boy exhales testily

and a child begins to cry –

for it was never the same question

twice. Each time there was

a subtle difference to it.

How do people live? implied

something substantially different

to How do people live? It was

a question of weighting: one

suggested method, the other

a question of will. Clearly,

to him, it was all a mystery

and a miracle. And who was not

in the queue that morning

who did not feel something stir,

as that man, with the worn trench-coat

and the unkempt grey hair, asked

and asked again, How do people live?

How do people live nowadays?

This new inflection brought the question

close. How could it not, when each day

we saw the world burn, flags on fire,

hatred woven through the air? This question

had a smell. It was acrid –

gunpowder, dying seas, a last

sour gasp. The sound

was of languages falling silent;

children crying, a mother’s despair.

Then, like a ringmaster, he cracked

the whip of that first question again,

as if he had cleared the decks

of the clogging world and we heard

with a new clarity: How do people live?

The question deepened now.

He was rowing us out to the centre

of a loch, where the waters were so dark

as to be impenetrable. But it was the only question

worth asking, though asking it made life

seem chancy. How do people live?

Where was the next breath

coming from? We were climbers

on a cliff of blue ice. We’d slip.

Nothing surer. The space was terrifying.

We watched a lottery ticket float into it,

as worthless as everything, now

that all we wanted was to hold an answer

to us – it was all that could save us.

How do people live? There was no

David Attenborough to tell us

how to make huts, to invent fire,

to carve a hole in the ice. We were far out.

Unreachable. How do people live? What more

could he have done but ask the question –

though asking it gave no relief?

He nodded slightly in his shabby coat, then left us,

to invent fire, to carve a hole for himself in the ice.

From The Poem Goes To Prison – Poems chosen by readers at HMP Barlinnie, edited by Kate Hendry (Scottish Poetry Library 2010).

In Praise of Coffee

Who first thought to pluck the coffee bean from a tree, dry it, do to it the complicated things that need attending to, and brewing a hot cup of the stuff? Like so many other human discoveries, the odds on this ever happening seem so remote as to defy imagining. I mean, why would anyone bother? And how many horrible concoctions did people try out before hitting on the right one? How many were fatal, and how many caused the ardent experimenter to call out ‘O God, why did I try to smoke/drink that?’ But there seems no lack of ingenuity in humans’ attempts to eat, drink, imbibe, smoke or snort just about every leaf, bean, bark or blossom under the sun. And why not.

I have just opened, and brewed a pot of the sample on the left of the picture, an espresso roast from Las Flores plantation, Nicaragua. It is delicious and strong, but unlike other dark roasts doesn’t leave any nasty metallic aftertaste. I wish I could share a cup with you, although rumour has it that Coffee a Go Go in Cardiff’s St Andrew’s Place have a small allocation, which is their guest bean today.

On my recent trip to VIII International Poetry Festival of Granada in Nicaragua, I retuned with my suitcase laden down (it hit 27 kilos so I had to plant some on Mrs Blanco – has anyone tampered with your luggage madam . . ) not with tomes of poetry (there was some of true value, and I think I got what I needed there) but with a selection of coffee beans. While there, we also enjoyed a tour of one plantation, where we learned, for example, that due to the delicacy of the small sprigs, the coffee beans have to be hand-picked with a gentle downward movement, because if the stems are bent back the wrong way, they will not produce fruit the next year. This is backbreaking and demanding labour, and cannot be carried out recklessly.

I spent several winters in my younger years picking olives, and (depending on the location, and the destination of the olive) this activity can be carried out with varying degrees of vigour, but none of them involve quite such a delicate technique as coffee-picking.

And then there’s the wages paid to the pickers. On most plantations this is minimal – and their living conditions appalling, which is why it is important to try and buy coffee from a responsible source – not easy when half the coffees in the supermarket are labelled under the ambiguous (and almost meaningless) ‘Fair Trade’ label.

A good cup of coffee is a priceless thing, and those beans have made quite a journey. It makes one wonder if there are any decent coffee poems. So I do a search, and am delighted to find there is an entire literature reflecting our love affair with the bean, notably in a site titled, usefully, a history of coffee in literature.

Here is an example, from the little known (early 19th century?) English poet Geoffrey Sephton, extolling the virtues of Kauhee (or coffee) as opposed to those nasty opiates that were all the rage at the time:

To The Mighty Monarch, King Kauhee

Away with opiates! Tantalising snares

To dull the brain with phantoms that are not.

Let no such drugs the subtle senses rot

With visions stealing softly unawares

Into the chambers of the soul. Nightmares

Ride in their wake, the spirits to besot.

Seek surer means to banish haunting cares:

Place on the board the steaming Coffee-pot!

O’er luscious fruit, dessert and sparkling flask,

Let proudly rule as King the Great Kauhee[1],

For he gives joy divine to all that ask,

Together with his spouse, sweet Eau de Vie.

Oh, let us ‘neath his sovran pleasure bask.

Come, raise the fragrant cup and bend the knee!

O great Kauhee, thou democratic Lord,

Born ‘neath the tropic sun and bronzed to

splendour

In lands of Wealth and Wisdom, who can render

Such service to the wandering Human Horde

As thou at every proud or humble board?

Beside the honest workman’s homely fender,

‘Mid dainty dames and damsels sweetly tender.

In china, gold and silver, have we poured

Thy praise and sweetness, Oriental King.

Oh, how we love to hear the kettle sing

In joy at thy approach, embodying

The bitter, sweet and creamy sides of life;

Friend of the People, Enemy of Strife,

Sons of the Earth have born thee labouring.

A modest epiphany

From left: John Galán (Colombia), Iman Mersal (Egypt), Frank Báez (Dominican Republic), Tom Pow (Scotland).

Sometimes a short poem hits the mark, for no particular reason, and without providing any easy way of explaining to others the random pleasure it delivers.

I am looking through Postales, an intriguing book of poems by the young Dominican poet Frank Báez – for me one of the finds of the Granada Poetry Festival – and I notice this little gem, a sweetly ironic homage to Ginsburg:

Miaow

I haven’t seen the best minds

of my generation and nor does it bother me.

In the original:

Maullido

No he visto las mejores mentes

De mi generación y ni me interesa.