Narrative Horror

A conversation with an old friend, while driving to Bristol airport earlier this month, led me back along the wild mountain tracks of memory, and an introduction to what psychologist Martin Conway refers to as the self-memory system (SMS) model of autobiographical memory.

In an article published in 2005 titled ‘Memory and the Self’, Conway argues that two of the central concerns of memory are correspondence and coherence. Correspondence refers to the essential accuracy of what we recall, and how we remember (or at least recount) our experience. Coherence, on the other hand, is the requirement to make our memories consistent with our current goals, beliefs and self-image. Conway’s insight lies in reminding us how personal memory is as often as not a trade-off between the distinct but competing demands of coherence and correspondence, between adhering to our contrived self-image at the same time as (supposedly) telling the truth about our past. This can often be an uncomfortable compromise. If the self-image is threatened by the inconvenient fact of contradiction, what is a person to do? It is easy to see how the serial fantasist simply invents new stories in order to bridge the gap between who they think they are and what actually happened.

Thinking about all of this, I am reminded of what Javier Marías terms El horror narrativo (narrative horror), the way in which one’s status, as well as one’s accomplishments and merits, can be tainted or destroyed by a single misfortune or a single moment of disgrace — when we have committed some deed for which we will never be forgiven, and for which we might not even be responsible, but which has been imposed or inflicted on us by others. Either way, every aspect of our life story’s, carefully nurtured up till then, can be overturned, thrown into question, or brutally exposed and ridiculed, all in an instant. The most obvious example of this, according to Marías, might be the way that a public figure, overly self-conscious of being such a big shot, might worry about events in their past lives and the way they might appear to others, if discovered — to such an extent that they live in terror that a moment of narrative horror might descend upon them and reveal to the world just what an abject individual they really are, how ill-suited they are to public office, and of how their lovingly tended self-portrait will be forever tainted by some indiscretion that ends their career. Sometimes, Marías reminds us, this can happen posthumously, for example when secrets are discovered that were kept safe during the individual’s lifetime. But as much as anything else, narrative horror overcomes us when the factors of correspondence and coherence do not meet up, and we are left with our narrative torn apart and shown to be an utter fiction after all.

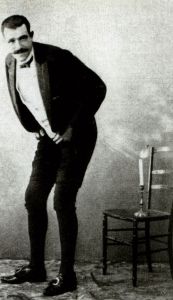

Javier Marías (1951-2022)

For me, narrative horror can extend into other areas, specifically the constant narrating done to ‘tell and tell’ something (of which, like most writers, I have no doubt been culpable myself). My awareness of this notion was probably brought about by a passage from Marías’ early novel The Dark Back of Time, which he begins with the words: “I believe I’ve still never mistaken fiction for reality, though I have mixed them together more than once, as everyone does, not only novelists or writers but everyone who has recounted anything since the time we know began, and no one in that known time has done anything but tell and tell, or prepare and ponder a tale, or plot one.” This passage inspired the rant that follows its citation in my memoir, The Vagabond’s Breakfast, when I wrote:

“This eternal recounting, this need to tell and tell, is there not something appalling about it – and not only in the sense of whether or not we consciously or intentionally mix reality and fiction? Are there not times when we wish the whole cycle of telling and recounting and explaining and narrating would simply stop – if only for a week, or a day; if only for an hour? The incessant recapitulation and summary and anecdotage and repetition of things said by oneself, by others, to others, in the name of others; the chatter and the news-bearing and the imparting of knowledge and misinformation and the banter and explication and the never ending, all-consuming barrage of blithering fatuity that pounds us from the radio, from the television, from the internet, the unceasing need to tell and make known? And whenever we recount, we inevitably embroider, invent, cast aspersion, throw doubt upon, question, examine, offer for consideration, include or discard motive, analyze, assert, make reference to, exonerate, implicate, align with, dissociate from, deconstruct, reconfigure, tell tales on, accuse, slander or lie.”

We are forever subject — or victim — of the stories we tell about ourselves. All the more reason to remain silent, keep schtum, never breathing a word to anyone about it, that thing that happened and which no one else knows about, but which keeps returning to you in the dead of night . . .

I will leave the last words on narrative horror to Marías, from Fever and Spear, the first book in his trilogy, Your Face Tomorrow, superbly translated by Margaret Jull Costa.

“Narrative horror, disgust. That’s what drives him mad, I’m sure of it, what obsesses him. I’ve known other people with the same aversion, or awareness, and they weren’t even famous, fame is not a deciding factor, there are many individuals who experience their life as if it were the material of some detailed report, and they inhabit that life pending its hypothetical or future plot. They don’t give it much thought, it’s just a way of experiencing things, companionable, in a way, as if there were always spectators or permanent witnesses, even of their most trivial goings-on and in the dullest of times. Perhaps it’s a substitute for the old idea of the omnipresence of God, who saw every second of each of our lives, it was very flattering in a way, very comforting despite the implicit threat and punishment, and three or four generations aren’t enough for Man to accept that his gruelling existence goes on without anyone ever observing or watching it, without anyone judging it or disapproving of it. And in truth there is always someone: a listener, a reader, a spectator, a witness, who can also double up as simultaneous narrator and actor: the individuals tell their stories to themselves, to each his own, they are the ones who peer in and look at and notice things on a daily basis, from the outside in a way; or, rather, from a false outside, from a generalised narcissism, sometimes known as “consciousness”. That’s why so few people can withstand mockery, humiliation, ridicule, the rush of blood to the face, a snub, that least of all … I’ve known men like that, men who were nobody yet who had that same immense fear of their own history, of what might be told and what, therefore, they might tell too. Of their blotted, ugly history. But, I insist, the determining factor always comes from outside, from something external: all this has little to do with shame, regret, remorse, self-hatred although these might make a fleeting appearance at some point. These individuals only feel obliged to give a true account of their acts or omissions, good or bad, brave, contemptible, cowardly or generous, if other people (the majority, that is) know about them, and those acts or omissions are thus encorporated into what is known about them, that is, into their official portraits. It isn’t really a matter of conscience, but of performance, of mirrors. One can easily cast doubt on what is reflected in mirrors, and believe that it was all illusory, wrap it up in a mist of diffuse or faulty memory and decide finally that it didn’t happen and that there is no memory of it, because there is no memory of what did not take place. Then it will no longer torment them: some people have an extraordinary ability to convince themselves that what happened didn’t happen and what didn’t exist did.”

How long can you stay focused on anything at all . . .

I have been wondering about the capacity of the mind to focus on anything for more than a few seconds at a time. A lot has been published on this topic in recent years, especially relating to children’s use of the internet and social media. An article I read somewhere suggested that the maximum attention span is around eleven minutes, but that seems optimistic: when engaged in mindfulness meditation, for example, it can be difficult to maintain focus on one’s breath for more than eleven seconds.

Nevertheless, and despite all evidence to the contrary, I decided one day to try and focus only on my breathing and on taking one step after another, over the course of a twelve mile walk. I would impersonate a being with no mental baggage, with ‘nothing extra’, as Shunryu Suzuki puts it. Despite the fact that I have tried this before, and failed, I want to see whether I can maintain a sustained awareness of myself as only a walking, breathing entity — or at least a being with this intention, which may or may not be the same thing — over the course of the entire walk. I know that I am setting myself up to fail again, but I will do it anyway, just to see . . .

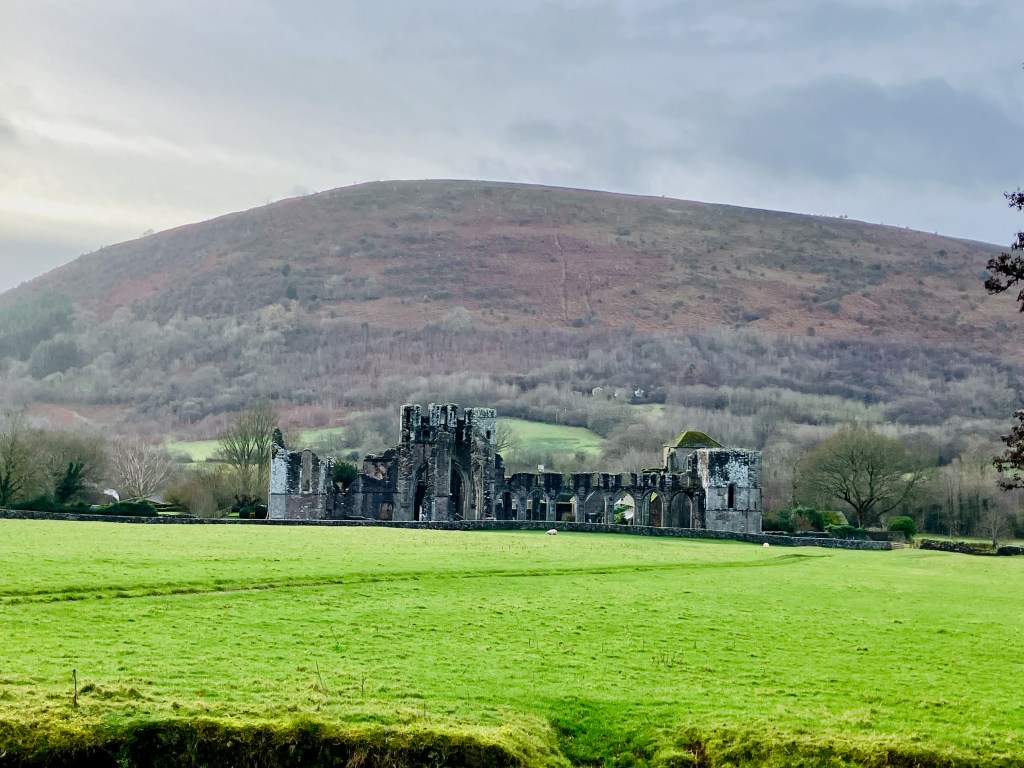

So, on a January morning in 2024 — the first day of the new year on which it is not pelting with rain — I set off on a circular walk from Llanthony Priory. My plan is to climb up to the Offa’s Dyke trail, follow it for a couple of kilometres, turn west down the steep track towards The Vision farm, take a right along the lane to Capel y Ffin, climb to the Ffawyddog (which separates this valley from Cwm Gwyne Fawr) and follow the ridge down to Bal Mawr and thence down Cwm Bwchel, back to Llanthony. Twelve miles, give or take. Six hours including picnic lunch and stops.

Before I get to the first turning, on the relatively flat stretch along the Offa’s Dyke path, I am doing pretty well. I am practising in the same way as I meditate, by breathing and focusing on my breath, step after step. I lose myself from time to time, of course, the monkey mind turns somersaults in the usual way, and I slip into the internal monologue occasionally, but I am doing OK, although, of course, I am not ‘getting anywhere’. Nor do I want to. There is, needless to say, nowhere particular to get to, except one step after another, one breath at a time.

But the fact is, however much I try to convince myself otherwise, I am crap at this. My mind is playing jumping jacks. Within minutes I am all over the place. I have no sense of being a consistent individual, a single thinking feeling entity for more than thirty seconds at a time, maximum. The fundamental thing that distinguishes me from the moorland pony with the swollen belly that I pass along the way is that while the pony is no doubt conscious, I am conscious that I am conscious, and I rather doubt that she is. I am conscious that I am conscious, and that is why I am putting myself through this pointless exercise. I’m not saying that the pony, or the walker’s dog that I see approaching on the far horizon is a lesser being, but I am pretty damn sure that neither of them is spending their time worrying about the permutations of their consciousness, or their failure to keep their attention on one thing at a time.

As I walk, I am getting a sense that there are two distinct ways of regarding the self, or one’s own inner personhood. The first type of consciousness is that I am aware of myself as a physical human being, a human being considered as a whole. This is the human being I encounter in the mirror when brushing my teeth or shaving, the one who looks back at me, and whom I dimly recognise as the same human being I have always been, albeit with obvious differences from the person I was, say, forty years ago, and with minor variations from the person I was yesterday. Let’s call this one the outer self.

The other type of self is, in Galen Strawson’s words, an ‘inner mental presence’, one who has the ability to observe and record the antics of the outer self. This ‘inner mental presence’ is the one I am trying to keep track of as I walk, and finding it incredibly difficult to do so. And, as I have (unthinkingly) just written ‘I’, this poses the question of a third participant, the ‘I’ that is monitoring the ‘inner mental presence’ as it, in turn, attempts to stay focused. Does this suggest three constituent parts to my identity? — (i) the physical body striding over the moor, (ii) the inner mental presence experiencing thoughts and feelings, and (iii) the ‘I’ making a note of all this, monitoring the ‘inner mental process’? Or are there more, an infinitely recursive number of selves, each of them monitoring the one within the adjacent ‘layer’ of selfhood? This is precisely the kind of conundrum posed by reading Borges for the first time, or by studying fractals, or taking LSD or magic mushrooms . . . and yet it is a valid mode of thought, because otherwise I would not be thinking it, surely?

Clearly, I have strayed from the original plan to stay focused on nothing but my breath and putting one foot in front of the other (was that the plan?). I now have to contend with the overwhelming issue of multiple selves, and how to select one among many . . .

Perhaps the most striking thing I can say about this inner mental presence is that, at best, one is in a state of constant renewal. As I mentioned in last week’s post, the poet Harold Brodkey says “our sense of presentness usually proceeds in waves, with our minds tumbling off into wandering . . . This falling away and return is what we are.” How true this feels, I think, as I pound the turf, the familiar muddy turf of these red sandstone hills. Despite the permanent feel of the place, and of my place within it, I cannot help but feel that something is always just beginning, and — whatever I am — I am a part of it. And yet, and yet . . . my mind keeps ‘tumbling off into wandering’, an awkward phrase that at once brings to mind the errant perambulations of a lost soul.

I turn off Offa’s Dyke path towards the valley and the descent gets pretty steep, and because of the rain, the track is slippery. As I near the bottom of the hill I look back and see a figure high above me on the same path, silhouetted against the skyline, utterly unmoving. It seems to be the figure of a man. The image reverberates with me in a curious way, almost as though it were lifted from a Caspar David Friedrich painting. It feels somehow prescient, as though this figure were not only observing me, but had also registered me observing him. The irrational thought occurs to me that this figure, this personage, is somehow significant, or will become so. It is one of those moments when you half-grasp a sense of something about to happen imminently, but in only the vaguest way. Half an hour later, at a gate that opens onto a field close to the valley road, the figure on the hill catches up with me. He is about the same age as me; that is, getting on in years. Without necessarily intending it, we fall into conversation. Neither of us, I suspect, is much given to chatting while on a walk: the very reason one does a walk like this is (often) that one wishes to be alone. Also, I sense — correctly, as it turns out — that he, if not exactly in a hurry, has somewhere to get to, which I do not. Not in the short term, anyway.

I see the road — he says, pointing at the lane that runs from Llanthony to Capel y Ffin — has finally been fixed. The stretch he is indicating has been under repair for many years. A sign proclaiming that the road is closed has warned motorists coming down (or up) the valley to that effect almost for as long as I care to remember. Oh good, I reply, adding that I have never taken any notice of the ‘Road Closed’ sign anyway. Ah, so you’re local, then, he retorts, with a lopsided grin. Well, kind of, I say. I grew up nearby but live in Cardiff . . . and you? It transpires he is from Capel itself, but has lived in Abergavenny for many years. It turns out he knew my father. ‘A legend’, he says. I let the comment hang there a while. I’m curious, but I don’t ask. Recognising some kind of kinship, perhaps, we talk about the different valleys of the Black Mountains, and their respective qualities. It turns out his own father had a special affection for the Grwyne fechan valley, as did mine. He enjoyed the quiet there, says the man.

We pass a cottage, once a farm, now a second home, like many other places in the valley. When we were children, the man says, we used to come carol singing here at Christmas — here and the other farms. He sounds happy at the memory rather than sorrowful at the fact that nearly all the farms hereabouts have been bought up by strangers from across the border, people from London and Bristol. But it makes me sad; no, it also makes me angry, but my anger is pointless, and not directed at any particular individuals, just at the disappearance of a way of life, sadness at the death of a small community, fragile as it was.

We approach the Grange, a large house and pony trekking centre, and the man explains that he has arranged to stop off for tea with an elderly relative who lives there. I continue alone, and climb to the Ffawyddog, where I take a break at a rock called the Blacksmith’s Anvil, sit and eat my sandwich, drink tea, and enjoy the view over the moor towards the Grwyne Fawr reservoir.

Within fifteen minutes, the man reappears, climbing the hill behind me. He has caught up with me, as I guessed he would, and stays a while longer, munching on a sandwich of his own. I tell him I wrote a novel set in the valley — The Blue Tent — and he expresses interest, and surprise, because he thought he had read everything published about the place. I tell him I’ll send him a copy, and he scribbles out his address in pencil, on a small notebook he carries with him. The taking of pencil and notebook on a walk in the hills reveals something about a person, I feel. My handwriting has improved since I retired, he comments, with a wan smile, although I have said nothing. I assume, correctly, that he will want to continue on his own, as he is a fast walker — ‘no one keeps up with me except my brother’ — and he needs to be at the Llanthony car park at 4.15 pm for his lift. There’s no way I could keep up with him, although I am no slouch myself. I let him leave, and within a couple of minutes he is almost out of sight. He stops still, briefly, near the rocks at Chwarel y fan, and it is a replay of the first time I saw him, above me on the hillside across the valley, silhouetted again the sky, statuesque, looking about him. And he vanishes into the amber light of the ebbing day.

Tlön, Uqbar, and the girl in the moon

Having fallen ill on the last day of teaching, the accumulated tensions of the semester finally erupting in an onslaught of snot, fever, and a hideous, raucous cough, I take to my bed in the hope that rest and warmth, accompanied by mugs of hot lemon and honey, will heal me. Given the horizontal advantage, after drifting in and out of sleep over the course of Saturday afternoon, cold rain pelting at the window, my thoughts drift, if not into unconsciousness, at least toward the unconscious.

Aware as I am of the various scribblings of Freud and Jung on this subject, and dawdling on YouTube, the opportunity arises to watch Jordan Peterson give a class on psychoanalytic theory. Curious to learn what the much-maligned Peterson has to say on this topic (delivered by way of a somewhat cursory psychoanalytic reading on the film Mulholland Drive) I find that – according to Peterson – Freud saw the unconscious as the place of hidden or ‘disguised secrets’, while Jung regarded it as the place of ‘knowledge that had not yet come to be’.

Leaving aside whether or not Peterson is correct in his framing of this difference, the notion that there is another version of knowledge that has ‘not yet come to be’ is intriguing, and certainly corresponds with my understanding of Jung, and of his followers Joseph Campbell and Marie-Louise von Franz, to name but two. But how are we to balance the world of everyday, conscious, ego-driven perception, with the restless, seething mass of subterranean ‘knowledge’ provided by the unconscious?

Having posed this question, I am pleased to come across two indications of how this might be translated into a clearer understanding. The first arrived later in the day when, still idling through YouTube, I find an account given by Marie-Louise von Franz about her first encounter with Jung, when she was eighteen years old and the Swiss psychoanalyst was fifty-eight, an age, the young von Franz thinks, which makes him ‘ready for the cemetery.’ Nevertheless, von Franz is enthralled, and she continues:

‘He [Jung] told that story which you can read in the Memories (Jung’s autobiography, Memories, Dreams, Reflections) about this girl who was on the moon and had to fight a demon, and the black demon got her. And he pretended, or he told it in a way as if she really had been on the moon and it had happened.

And I was very rationalistically trained from school so I said indignantly, “But she imagined to be on the moon, or she dreamt it, but she wasn’t on the moon.”

And he looked at me earnestly and said, “Yes she was on the moon.”

I still remember looking over the lake there and thinking, “Either this man is crazy, or I am too stupid to understand what he means.”

And then suddenly it dawned on me, “He means that what happens psychically is the real reality, and this other moon, this stony desert which goes round the earth, that’s illusion, or that’s only pseudo-reality.”

And that hit me tremendously deeply. When I crawled, rather drunk into bed because he gave us a lot of Burgundy that evening, I thought, “It will take you ten years to digest what you experienced today.”’

In terms of our understanding of the unconscious, this story’s insistence that psychic reality is no less real than the reality of the everyday is, to say the least, instructive.

It is worth bearing in mind, at this point, that the unconscious, according to Jung, has no sense of its own or its bearer’s mortality, and is not constricted by any kind of temporality. The past, the present and the future are equally at its disposal.

Now, this morning, not entirely at random, I find myself re-reading Borges’ story ‘Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius’, in the translation by Alastair Reid, where Borges describes a fictitious country (Uqbar) whose mythology originates in a mysterious world called Tlön.

Now, this morning, not entirely at random, I find myself re-reading Borges’ story ‘Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius’, in the translation by Alastair Reid, where Borges describes a fictitious country (Uqbar) whose mythology originates in a mysterious world called Tlön.

I come to stop at a passage describing one of the ‘oldest regions of Tlön’ in which ‘it is not an uncommon occurrence for lost objects to be duplicated. Two people are looking for a pencil; the first one finds it and says nothing; the second finds a second pencil, no less real, but more in keeping with his expectation. These secondary objects are called hrönir and, even though awkward in form, are a little larger than the originals.’

Putting it simply – and in terms that Borges himself might well have avoided – Tlön is the unconscious of Uqbar; the realm of myth and dream. And for the sake of the story I’d say that within the unconscious, the search for the pencil results in two discoveries: in one of these the pencil is the ‘authentic’ pencil that the protagonist lost, and in the other version, the pencil is a simulacrum (or hrön), a possible version of itself.

WTF?!

Would it be too much to map that idea from von Franz, of the ‘reality’ of unconscious experience onto this discovery of the ‘real’ pencil; with the second, somewhat clumsier, more ‘awkward’ and ‘larger’ (as in ‘larger than life’) second pencil corresponding to the ‘real life’ acting out of the story of the girl and the demon? By which I mean, of the two pencils, the ‘original’ is the one that appears to the psyche; the second, to the world? And if there is a second pencil, no doubt there exists a third; in other words multiple hrönrir representing the infinite versions of oneself and one’s actions in the multiverse (see Blanco’s last blog but one).

Or has my head cold taken this beyond the grasp of the intellect alone?

There is more, of course (there always is . . .)

In a manner that is never clearly elaborated, the artefacts and objects of Tlön have infiltrated our own world. In other words: ‘Contact with Tlön and the ways of Tlön have disintegrated this world.’ Things do not unfold well in Borges’ story.

Although first published in 1940, the postscript to Borges’ story is dated 1947. In other words he places the postscript to his story seven years after its publication, by which time World War Two has ended, and a New World Order is taking shape. This information (unknowable to Borges at the time of his writing) lends particular valence to the following paragraph:

‘Ten years ago, any symmetrical system whatsoever which gave the appearance of order – dialectical materialism, anti-Semitism, Nazism – was enough to fascinate men. Why not fall under the spell of Tlön and submit to the minute and vast evidence of an ordered planet? Unless to reply that reality, too, is ordered. It may be so, but in accordance with divine laws – I translate: inhuman laws – which we will never completely perceive. Tlön may be a labyrinth, but it is a labyrinth plotted by men, a labyrinth destined to be deciphered by men.’

I check out critical responses to the Borges story, and then recall, among the many commentaries, Peter Gyngell’s unpublished PhD thesis, The Enigmas of Borges, and the Enigma of Borges (2012). Gyngell considers ‘Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius’ to be, to some extent, a reflection on ‘the scepticism and despair for Argentina’s future that Borges shared with his contemporaries in the late 1930’s; and, above all, a reflection of his fears at that time of the domination of Argentina by the new and growing imperial power of the USA.’ In Gyngell’s reading, the takeover by Tlön represents the commercial and cultural influence of the USA permeating the world.

‘I would also submit’, writes Gyngell, ‘that Tlön is not a complete success. The reader is presented not only with two totally incompatible themes — heavy philosophical satire and economic politics — but also with a story that is overwritten, at least by Borges’ standards. ‘Tlön’ is the longest story in the Collected Fictions; and I suggest that this is brought about, at least in part, by Borges’ vain attempt to reconcile its irreconcilable themes.’

I personally still retain a fondness for the story – which was the first by Borges that I ever read – particularly for the following paragraph, with which I will end this post, and which I remember citing in my first essay as an anthropology undergraduate many years ago; apropos of what precisely, I simply cannot remember:

‘Things duplicate themselves in Tlön. They tend at the same time to efface themselves, to lose their detail when people forget them. The classic example is that of a stone threshold which lasted as long as it was visited by a beggar, and which faded from sight on his death. Occasionally, a few birds, a horse perhaps, have saved the ruins of an amphitheatre.’

Montaigne and the power of the imagination

Reading Montaigne’s essay ‘On the power of the imagination’ I am struck by how differently the imagination was viewed in the early modern period. Indeed, understanding of the term is confined to its more negative associative powers. ‘I am one of those who are very much influenced by the imagination’, writes Montaigne, ‘[And] my art is to escape it, not to resist it . . . I do not find it strange that imagination brings fevers and death to those who give it a free hand and encourage it.’

It is only in the Romantic period, when the imagination is associated by Wordsworth and Coleridge with creative power or the poetic principle – the link between the visible and invisible worlds – that the word accrues the significance we attach to it today.

But for Montaigne, imagination is nothing but trouble. Impotence, every manner of psychosomatic disorder, even the tendency to fart, all are blamed on the dreaded imagination. ‘The organs that serve to discharge the bowels have their own dilations and contractions outside of the control of the wishes and contrary to them . . . Indeed I knew one [such organ] that is so turbulent and so intractable that for the last forty years it has compelled its master to break wind with every breath. So unremittingly constant is it in its tyranny that it is even now bringing him to his death.’ The implication is that the imagination works on the individual who wields it– or rather is wielded by it – in the same tyrannical fashion as the bizarre ‘organ’ located in the bottom acts upon its owner.

What is strange in this essay is the to-ing and fro-ing between the pre-modern associations Montaigne makes with acts of witchcraft and other psychic and psychosomatic disturbances for which the imagination is blamed, and the task he sets himself as a writer. In a particularly lucid moment towards the end of the essay, we begin to hear the more familiar voice of the essayist at his best, extolling the virtues of brevity:

‘Some people urge me to write a chronicle of my own times. They consider that I view things with eyes less disturbed by passion than other men, and at closer range, because fortune has given me access to the heads of various factions. But they do not realise that I would not undertake the task for all the fame of Sallust; that I am a sworn foe to constraint, assiduity and perseverance; and that nothing is so foreign to me as an extended narrative.’

A Journey into Memory

When I remember things from childhood or early adulthood, it often feels as though I am a passive subject, a receptacle or vessel, and the process of remembering becomes one in which memory is seeking me out, digging its way into my sense-making apparatus, rather than there being any sort of ‘I’ trying to make sense of the things remembered.

I am all too aware that as far as memories are concerned, it is the act of construction (more accurately reconstruction) that matters, of making the bits fit our self-narrativisation. In other words, as Gabriel García Márquez put it: ‘Life is not what one lived, but what one remembers and how one remembers it in order to recount it.’

In his memoir, Other People’s Countries (subtitled A Journey into Memory), Patrick McGuinness asks fascinating questions about the way that identity is rooted in memory, more specifically in the way that we remember. “Trying to remember is itself a shock, a kind of detonation in the shadows, like dropping a stone into silt at the bottom of a pond: the water that had seemed clear is now turbid (that’s the first time I’ve ever used that word) and enswirled.” On reading this passage, which comes on Page 7 of the book, I found it noteworthy that McGuinness comments on the fact that he has not used the word ‘turbid’ before, which immediately casts suspicion on the observation, because one wonders whether, by commenting on memory’s cloudiness and turbidity, he has merely dislodged an existing memory, and is therefore, perhaps, not ‘using the word for the first time’ at all. And how telling that his use of the word ‘turbid’, and his comment on that usage, should immediately be followed by a neologism, ‘enswirled’.

In his memoir, Other People’s Countries (subtitled A Journey into Memory), Patrick McGuinness asks fascinating questions about the way that identity is rooted in memory, more specifically in the way that we remember. “Trying to remember is itself a shock, a kind of detonation in the shadows, like dropping a stone into silt at the bottom of a pond: the water that had seemed clear is now turbid (that’s the first time I’ve ever used that word) and enswirled.” On reading this passage, which comes on Page 7 of the book, I found it noteworthy that McGuinness comments on the fact that he has not used the word ‘turbid’ before, which immediately casts suspicion on the observation, because one wonders whether, by commenting on memory’s cloudiness and turbidity, he has merely dislodged an existing memory, and is therefore, perhaps, not ‘using the word for the first time’ at all. And how telling that his use of the word ‘turbid’, and his comment on that usage, should immediately be followed by a neologism, ‘enswirled’.

These are nice illustrations of the way that language, our use of it, and its use of us, can be an element in the process of remembering. I am thinking in particular of those laden words which, when they crop up, immediately bring with them a sequence of memories and associations. I remember reading somewhere that our memory of language is the best reason why one should not translate into a language that is not our mother tongue. Words carry their own baggage with them: when you hear certain words, they spark off a whole sequence of associative meanings and memories, stretching back to childhood, that would simply not be available to an individual who has learned a language as an adult.

Childhood is the source of many of these word-memories. Like smells or taste (Proust’s oft-cited madeleine), words, long forgotten or unused, are capable of eliciting entire submerged worlds. But is it the memory of the word itself that achieves this, or the memory of a memory? As McGuinness speculates:

‘And as with so much of that childhood, I seem to remember not the things themselves but the memories of the things, as if the present I experienced them in was already slowing up and treacling over, fixing itself in a sepia wash.’

There are so many good things in this book, things that make you reach for a pencil, or else just stop in your tracks and reflect about the words you have just read. You can dip in, pick a page at random, and come out with some crystallized memory, or some jewel of detailed observation.

Other People’s Countries is, on one level, about a house in Bouillon, in the Ardennes region of Belgium. The house belonged to McGuinness’ family (his mother was Belgian) and was the author’s own childhood home. The book is divided into many short chapters: in this way they resemble the rooms of a large house, perhaps Quintilian’s House of Memory. I’ll conclude with one of my favourite chapters, titled ‘Keys’, which follows in its entirety:

‘Watching an old police procedural, probably a Maigret, sometime in the early eighties while convalescing from glandular fever (an illness I experienced more as convalescence than as actual illness: I felt as if I was simply recovering from something, rather than actually having the something to recover from in the first place), it came to me: a thief pushing a key into putty so that it’s outline would be caught in the relief and he could copy it, then burgle the house.

That was memory, I realised: a putty with which you make another key, which would open the same door, but never quite as well. In no time, you’d be burgling your own past with the slightly off-key key that always got you in though there was less and less to take.’

Why Writers Drink

“An alcoholic may be said in fact to lead two lives, one concealed beneath the other as a subterranean river snakes beneath a road. There is the life of the surface – the cover story, so to speak – and then there is the life of the addict, in which the priority is always to secure another drink.”

Nothing remarkable about this, you might think, except that it mirrors almost exactly what Ricardo Piglia writes about the structure of the short story: that the outer, surface narrative, always contains and conceals a parallel interior story. This is interesting because it poses the extraordinary thesis that a human life is always about (at least) two narratives, the overt and visible, and the covert or hidden. In the case of the addict, the duality of these narratives is especially extreme, because the parallel interior or subterranean story – even if initially concealed or invisible – eventually breaks out into awful visibility, affecting all those in the immediate vicinity.

Even if one takes the subtitle with a pinch of salt, Olivia Laing’s The Trip to Echo Spring: Why Writers Drink, proves a fascinating read, exploring the relationship of six famously bibulous American writers with the bottle. The lives of Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Tennessee Williams, John Cheever, Raymond Carver and John Berryman are put under the microscope and – unsurprisingly – a lot of very messy stuff comes into view. However the book is beautifully written, and displays a profound understanding of both her subject matter and her subjects. Perhaps of all these cases, Fitzgerald’s was the greatest waste, while Berryman, with his astonishing grandiosity, provided the darkest farce. Of Berryman’s final years. Laing writes:

Even if one takes the subtitle with a pinch of salt, Olivia Laing’s The Trip to Echo Spring: Why Writers Drink, proves a fascinating read, exploring the relationship of six famously bibulous American writers with the bottle. The lives of Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Tennessee Williams, John Cheever, Raymond Carver and John Berryman are put under the microscope and – unsurprisingly – a lot of very messy stuff comes into view. However the book is beautifully written, and displays a profound understanding of both her subject matter and her subjects. Perhaps of all these cases, Fitzgerald’s was the greatest waste, while Berryman, with his astonishing grandiosity, provided the darkest farce. Of Berryman’s final years. Laing writes:

“That’s what alcoholism does to a writer. You begin with alchemy, hard labour, and end by letting some grandiose degenerate, some awful aspect of yourself, take up residence at the hearth, the central fire, where they set to ripping out the heart of the work you’ve yet to finish.”

The Trip to Echo Spring: Why Writers Drink is an excellently researched book on a difficult topic. It is filled with fascinating digressions and integrates the author’s findings with a journey she herself undertakes across the United States in pursuit of her subjects’ homes and histories.

On Not Getting It

Curiosity can sometimes be more satisfying, more enhancing, than the mere consolation of achievement.

A while ago I wrote here on Kafka’s claim that in spite of knowing how to swim, he had not forgotten what it feels like to not know how to swim – and consequently the achievement, or consolation of ‘being able to swim’ was only of any value when weighed against the state of curiosity and mystery of not knowing how to swim.

Or something like that.

Adam Phillips, in his excellent book Missing Out, says something very close to this. In the chapter ‘On Not Getting It’ he writes that sometimes ‘not getting it’ (whatever ‘it’ might be – knowing how to swim, or winning some straightforward or else obscure object of desire) is more interesting than ‘getting it’. He imagines a life ‘in which not getting it is the point and not the problem; in which the project is to learn how not to ride the bicycle, how not to understand the poem. Or to put it the other way round, this would be a life in which getting it – the will to get it, the ambition to get it – was the problem; in which wanting to be an accomplice didn’t take precedence over making up one’s mind.’

There is something very appealing about this notion of ‘not getting it.’ Here’s more:

‘What I want to promote here is the alternative or complementary consideration; that getting it, as a project or a supposed achievement, can itself sometimes be an avoidance; an avoidance, say, of our solitariness or our singularity or our unhostile interest and uninterest in other people. From this point of view, we are, in Wittgenstein’s bewitching term, ‘bewitched’ by getting it; and that means by a picture of ourselves as conspirators or accomplices or know-alls.’

For now, I am surprisingly happy to be bewitched by the notion of not getting it; to remain enhanced if occasionally bewildered by my inability or disinclination to get it.