The art of kissing

Portada – El desayuno del vagabundo

The principal purpose of this trip – to Buenos Aires and Santiago de Chile – is to attend the launches in those two cities of The Vagabond’s Breakfast in Spanish. This is being undertaken by Argentine publishers Bajo la luna, and the Chilean outfit LOM.

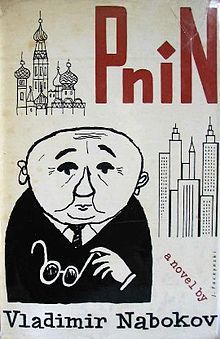

The book covers show a certain consistency of theme, which, at least in part, reflects the content of the book, although the Argentinian cover, while attention-grabbing, perhaps gives a misleading impression of irreversible dipsomania. Strangely, our first full day in Buenos Aires, we walked into a café, coincidentally called Poesía (poetry) to be met by a wall with a very similar façade.

So, on Monday I was picked up by LOM’s publicity person, Patricia, and taken to the University of Santiago to give a lecture – or so I thought – on Dylan Thomas, R.S. Thomas and David Jones. Having prepared this lecture, and given a version of it for the British Council in Buenos Aires (in English) I was not too worried about giving the same talk in Spanish. However, as often happens, there was a degree of confusion on the part of the university as to what exactly I was going to talk about, and when I arrived at the lecture hall I was confronted by a poster featuring a photo of myself wearing a straw hat, under the heading ‘Cómo un escritor se transforma en traductor’ – ‘How a writer turns into a translator’; an act of metamorphosis that I had never consciously given any thought to (but perhaps easier to tackle than ‘How a writer turns into a gardener’), which the hat might suggest, and since I was accompanied by my translator, the excellent Jorge Fondebrider, I thought: what the hell, why not. We’ll do it as a conversation, suggested Jorge. You’ll cope, he added, encouragingly.

In the hall, having successfully managed a sound check, the students and their lecturers filed in, rather a lot of them. They were extremely kind and attentive (only two of them actually fell asleep), while I wittered on about things that I hoped made sense, and which no one directly contradicted, all the while being prompted and prodded into acts of self-revelation by the industrious Señor Fondebrider. Questions followed, of a most informed kind – the students were studying for degrees in either translation or English, and when it was over, I walked out into the warm sunshine with the sense that another challenge had been overcome, another milestone passed.

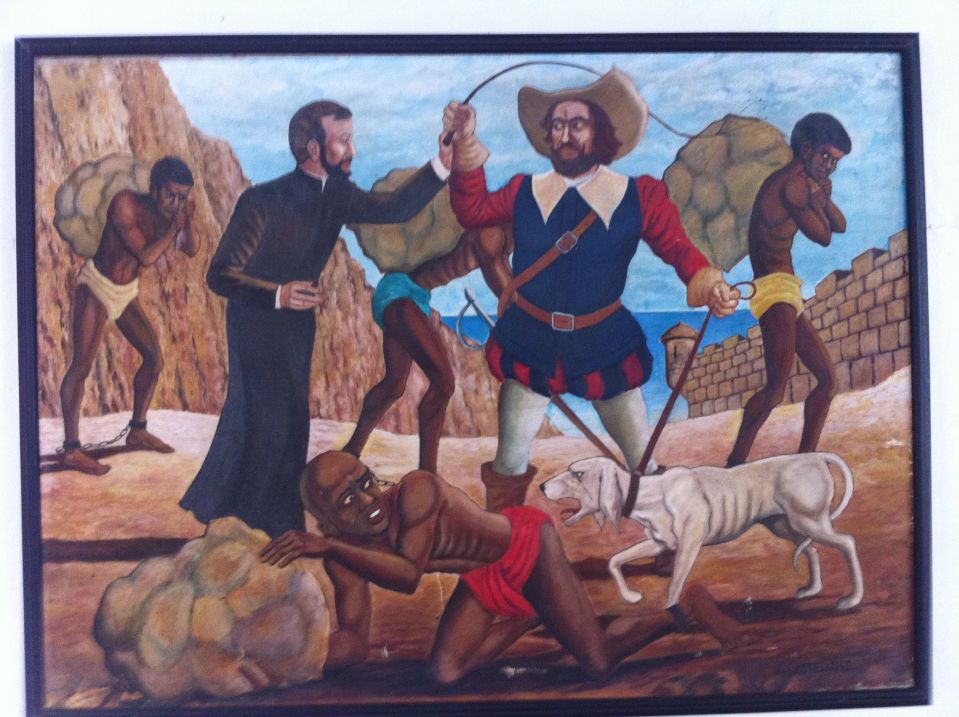

After lunch, I took a walk in the nearby park – situated on a steep hill, named Santa Lucia – directly opposite my hotel. It was here that Pedro de Valdivia, the conquistador and founder of Santiago, first pitched camp. Today, however, it is filled with courting couples, dotted like coupling worms across the hillside, all of them kissing as though it were the national sport. For obvious reasons I couldn’t take any photos: it would have been hard to justify as an act of research, but I have never witnessed such dedicated kissing; a wholesome, almost spiritual act of collective union; something like a Korean mass wedding, all entwined on the grass of the hill where Pedro de Valdivia once made camp with his 500 battle-weary conquistadores.