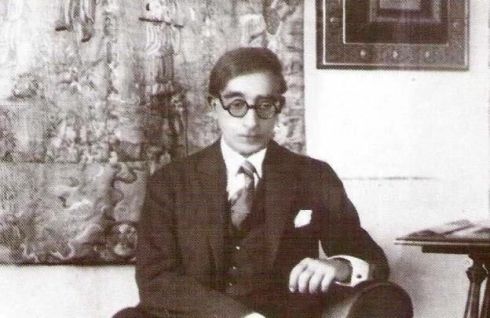

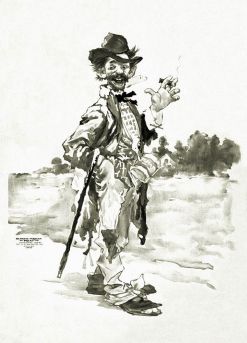

C.P. Cavafy (from the Cavafy archive)

For a long time, while I was tramping around southern Europe, escaping the collective embarrassment that was Britain in the 1980s, I carried with me the poems of CP Cavafy. Other books I picked up and discarded along the way, but Cavafy, in one edition or another, stayed with me for much of the decade. I forget the precise circumstances that led to me making this choice, but most likely it was not a choice at all; I suspect the book was dropped into my bag by a passing sprite, concerned for the welfare of an ephebe like myself, setting out into solitary exile to learn, among other things, the road of excess and the skills of guile and trickery. It would suit my story if this were the case, but the truth is I had been reading Cavafy since I was sixteen, and once he had become a staple of my travels, I didn’t feel properly equipped without him. A slim volume, joined during those early years by Borges’ Fictions and Calvino’s Invisible Cities. These three books had three things in common: they were all small-scale and dense; they all subverted familiar stylistic mannerisms; and they were all conceived in the element of mercury. One thing I didn’t know then was that forty years later I would still be reading Cavafy, with more curiosity than ever.

If we are lucky, we get the writers we deserve, and at the right time of life. Reading Cavafy at a young age nurtured in me the then enthralling (but now merely fashionable) notion that time is not a linear construct, but rather resembles a shifting, mutable state in which past and present might be accessed simultaneously. Cavafy’s poetry, as Patrick Leigh Fermor once wrote, skilfully interweaves time and myth and reality, allowing for a particular kind of mutability, an ability to flit between perceptive modes that, once grasped, will stay with the reader always. If that sounds grandiose, I would like to clarify: there is no distinction in these poems – I would like to say in life, also – between what is imagined and the literal or mechanistic world of everyday understanding, and we must appreciate that this is essential to a proper appraisal of Cavafy. There is no point in conceding to the sordid demand for what ‘really happened’, claiming that any other version is a fantasy or a dream, and that reality is ‘out there’, the other side of the window, any more than one can discern, in Cavafy’s work, between the literal Alexandria and the one held in his imagination. In Cavafy’s poetic world the two are one and they merge, diverge and re-converge continually.

When I was eighteen I spent a summer living in an abandoned shepherd’s hut on a hillside overlooking the Libyan sea in southern Crete, near the tiny village of Keratokambos. Reading outside one evening, I heard an exchange of voices. In the near distance, some way above me, a man and a woman were calling to each other, each voice lifting with a strange and powerful vibrancy across the gorge that lay between one flank of the mountain and the next. Only the nearer figure, the man, was visible, and his voice seemed to rebound off the wall of a chasm, half a mile away. The woman remained out of sight, but her voice likewise drifted across the gorge, with crystalline clarity. There were perhaps a dozen exchanges: and then silence. I listened, spellbound. And that brief exchange, that shouted conversation, with its strange sounds, the tension between the voices, the exhalations and long vowels echoing off the sides of the mountain, would haunt me for years, haunts me still. They seemed to me to be speaking across time, that man and woman. Their ancestors, or possibly they themselves, had been having that conversation, exchanging those same sounds, for millennia. It was, for me, a lesson in the durability of human culture and at the same time, the incredible fragility of our lives; the conversation, the calling across the chasm, represented our ultimately solitary and unique chance at communication with a presence beyond ourselves. It was the vocal correlative of a strange sensation that I had experienced since first arriving in Crete: everywhere I went I was walking on bones, walking on the bones of the dead; and now I was hearing the echo of their voices as well.

In ‘Ionic’, translated more recently by Daniel Mendelsohn as ‘Song of Ionia’, Cavafy sums up an exemplary moment, suggesting that despite the destruction of their monuments and statues, the old gods still dart among the hills on the coast of Ionia (today’s western Anatolia), and it concludes with the lines:

When an August morning dawns over you,

your atmosphere is potent with their life,

and sometimes a young ethereal figure

indistinct, in rapid flight,

wings across your hills.

Here, the ‘young ethereal figure’ is surely Hermes. He is, after all, the winged god, and the god of transition and boundaries, and therefore more than likely to be seen at dawn, in the breach between night and day. Perhaps the Hermes association is personal, owing to the fact that in my experience, Hermes, god of travellers, was almost always the one who came to sort out the mess after Dionysos had wreaked his havoc. It seems likely, according to Daniel Mendelsohn’s wonderfully thorough notes that Cavafy, too, was thinking of Hermes, although I did not know this when I first read the poem.

That the past cohabits eternally with the present is a specifically Cavafian notion, and this subversion of linear time was the first thing I learned from his poetry. The second was his unique conceptualisation of place, in relation to the city with which his name has become ineluctably associated, Alexandria. As Edmund Keeley points out, Cavafy was the first of his contemporaries (woh included Yeats, Pound, Joyce and Eliot in the English-speaking world) to ‘project a coherent poetic image of the mythical city that shaped his vision’. His poetic vision – even when concerned with matters of erotic desire, which it often is – involves a constant pursuit of ‘the hidden metaphoric possibilities, the mysterious invisible processions, of the reality one sees in the literal city outside one’s window’. Cavafy takes the idea of the city and expands upon it so that it carries mythic significance. The poem he chose to begin his first pamphlet of work, distributed among friends, is, significantly, ‘The City’. The poem is addressed to one whose life is bound by literal time and literal thought while, by contrast, the poet-narrator lives according to other parameters, which are timeless. Like other great poets Cavafy mythologises a personal landscape so that it becomes universal:

You won’t find a new country, won’t find another shore.

This city will always pursue you.

You’ll walk the same streets, grow old

in the same neighbourhoods, turn grey in these same houses.

You’ll always end up in this city. Don’t hope for things elsewhere:

there’s no ship for you, there’s no road.

Now that you’ve wasted your life here, in this small corner,

you’ve destroyed it everywhere else in the world.

The poet’s difficulties over the composition of ‘The City’ – fifteen years lapsing between the first draft in 1894 and publication – are perhaps a reflection of Cavafy’s uncertainty over whether or not he wanted to settle permanently in Alexandria, or himself ‘find some other city’, like the protagonist of his poem. ‘What trouble, what a burden small cities are’, the forty-four year-old poet complained in an unpublished note, dated 1907. He apparently made up his mind to stay by 1910, the year that ‘The City’ was published. It would seem that around this time he experienced an epiphany or at least a shift in his trajectory as a writer, deciding that his destiny lay with Alexandria, and that he would probably never leave. The choice of ‘The City’ as the lead poem in published selections of his work is as intentional as, say, Wallace Stevens’ insistence on ‘Earthy Anecdote’ opening all collected editions of his poetry. Alexandria became, from that point on, the principle vehicle for his poetic imagination. Conscious of this, he again addresses the theme of leaving the city – actually of being abandoned by the personified city – in ‘The God Abandons Anthony’, when the speaker admonishes the Roman general, who was closely associated with the god Dionysos, at the moment of departure:

When suddenly, at midnight, you hear

an invisible procession going by

with exquisite music, voices,

don’t mourn your luck that’s failing now,

work gone wrong, your plans

all proving deceptive – don’t mourn them uselessly:

as one long prepared, and full of courage,

say goodbye to her, to Alexandria who is leaving.

Above all, don’t fool yourself, don’t say

it was a dream, your ears deceived you:

don’t degrade yourself with empty hopes like these . . .

It is this self-degradation with false hopes, this yearning for the sacred centre, the object of desire that can never be attained, the love that will never be requited, which makes of all of us an Anthony. Whenever one thinks one has arrived at one’s destination, then will be the time to move on. There is no way of making peace with any objective, real or imagined, until one has first made peace with oneself, and the process is self-perpetuating, and the cities mount up. ‘The more you travel’ as the Turkish poet Adnan Özer writes, ‘the more cities you will find within yourself’.

So, the second thing I learned from Cavafy was that the city is a cypher for the self, reflecting our fragmented or multiple selves. We know that Cavafy is speaking of Alexandria, but we also know that the city is a state of mind – one’s personal predicament, and the human predicament also – from which we can never be free.

The third thing I learned from Cavafy is that we are always at risk of misreading the signs and portents that surround us: arrogance and self-satisfaction dim our vision and make us ridiculous. It is a favourite theme of Cavafy’s, most often delivered with a profound sense of irony. Let us consider the poem ‘Nero’s deadline’:

Nero wasn’t worried at all when he heard

what the Delphic Oracle had to say:

“Beware the age of seventy-three.”

Plenty of time to enjoy himself.

He’s thirty. The deadline

the god has given him is quite enough

to cope with future dangers.

Now, a little tired, he’ll return to Rome –

but wonderfully tired from that journey

devoted entirely to pleasure:

theatres, garden-parties, stadiums . . .

evenings in the cities of Achaia . . .

and, above all, the delight of naked bodies . . .

So much for Nero. And in Spain Galba

secretly musters and drills his army –

Galba, now in his seventy-third year.

At a superficial reading, the conceited, megalomaniac Nero, cosseted by the apparently safe verdict of the oracle, is undone by his comprehensive misunderstanding of its hidden message. But as Mendelssohn points out, the poem does more than make fun of Nero’s self-satisfied complacency, it puts forward Galba as the avenging hero, come from obscurity in his old age to save Rome. However, Galba, in turn, was a disaster for Rome, his greed and lack of judgement causing him to be murdered seven months after his accession as Emperor, on the orders of Marcus Salvius Otho, a fellow-conspirator against Nero. (Otho, incidentally, lasted only three months as Emperor before stabbing himself in the heart). ‘Nero’s deadline’ offers a cinematic vignette of power’s corrupting influence. And by omitting Galba’s own downfall – assuming, as he so often does, that the interested reader, if curious enough, will find out – Cavafy adds a layer of hidden significance to a piece that already works as a denunciation of grandiosity and hubris. The poem reveals betrayal lying beneath betrayal, all of it stemming from overreaching and a smug belief in one’s own achievements, only for each incumbent to meet with a grisly end.

I wanted to write this essay in order to find out why Cavafy has held such a longstanding fascination for me as a reader (and therefore as a writer, since the two activities are composite: we read, at least in part, in order to learn, or to steal). I have discussed three things that are particularly important in my own understanding of his work. But there is something else, greater than the sum of its parts, which asserts this man’s comprehensive poetic vision. Cavafy was a poet who, throughout his life, was – in Seferis’ words – “constantly discovering things that are new and very valuable”. It may be that this capacity for discovery, a reflexivity regarding his personal as well as a collective Hellenic past, his subtly revelatory intelligence, are somehow transmitted onward, and we, as readers, are infected by his own enthusiasms. “He left us with the bitter curiosity that we feel about a man who has been lost to us in the prime of life,” wrote Seferis. This is not simply on account of his relatively small output, but because of its seeming unity of construction and purpose, its sense of unfulfilled possibility, and the poet’s curiosity at being in a world in which past and present merge in an invisible procession.

Translations from the Greek are by Edmund Keeley & Philip Sherrard in C.P. Cavafy: Collected Poems, Chatto & Windus, 1990. The references to Daniel Mendelssohn concern the notes to his own translations in C.P. Cavafy: Complete Poems, Harper Press, 2013.

First published as ‘An Invisible Procession: How reading Cavafy changed my life’, in Poetry Review, 103:3 Autumn 2013.

0.000000

0.000000