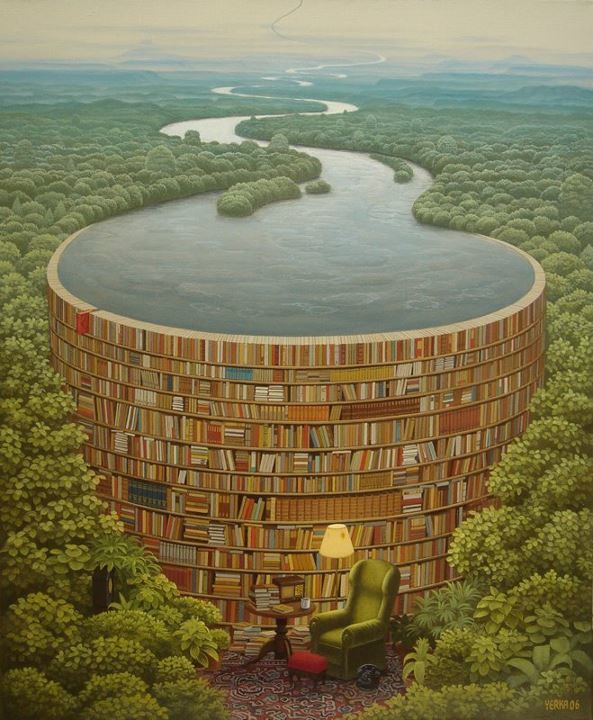

Just see where it takes you

Here at the end of things, a big drop, endless forest. Things fall away.

Here at the end of things where the forest is the world. A book falls on my head and I start into wakefulness. Never could I understand the cruel logic of beginnings.

Whoever might have predicted that I would wake up here?

Many years ago, I read a book by Ursula Le Guin called The Word for World is Forest. I can’t remember anything about the book, other than liking its title. It is a science fiction story with ecological leanings, that much I remember, and was apparently the inspiration behind the film Avatar. I probably wouldn’t read such a book now, my tastes have changed. In those days I read whatever was around. There is, as far as I know, no library in that book. Here, though, the library is the world. There are probably no dogs, but I can’t be sure of that.

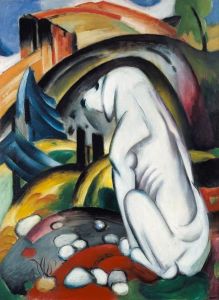

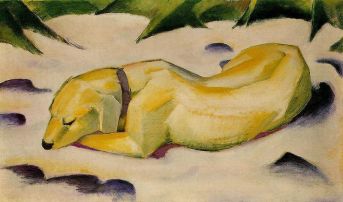

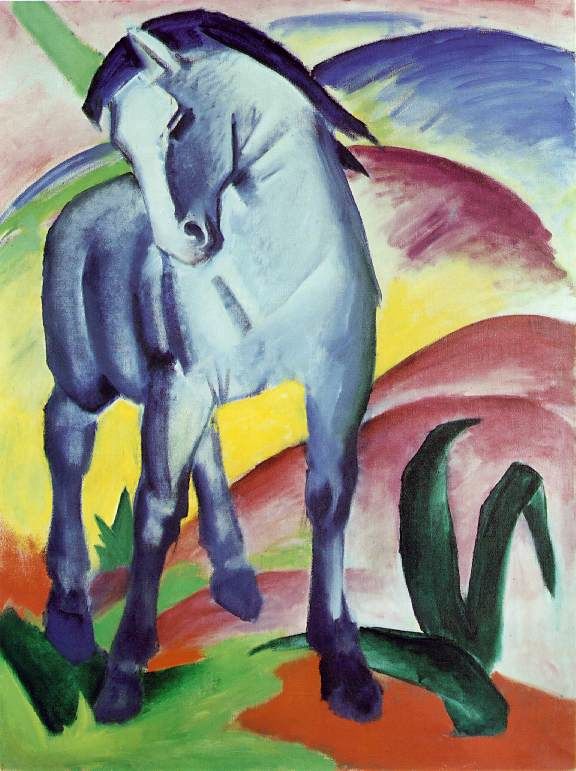

Here are two pictures of dogs by Franz Marc, the German expressionist painter.

We know that Franz Marc had a dog, but not whether this is it, in the painting titled White Dog, or another, Dog in the Snow, in which the animal appears to have a yellow or a tawny coat, perhaps in contrast to the snow in which it lies.

I suspect that the pictures are of one and the same dog, Marc’s companion, with whom he took long walks in the Bavarian hills. So the story goes, at least.

I rely on a mix of biographical snippets, picked up in some art book, many years ago, remembering only the detail that Marc took long strides (he was a large man) and that his dog resembled his master in distinctive ways, the two of them sharing a strength of character and mildness of disposition as noted by the unknown, possibly fictitious memoirist.

And now I take this memory for granted, have even placed the reference to character and disposition in italics, because I have convinced myself.

The story cries out for authentication. The dog, in two portraits, offers something that approaches evidence.