Q&A with Gary Raymond

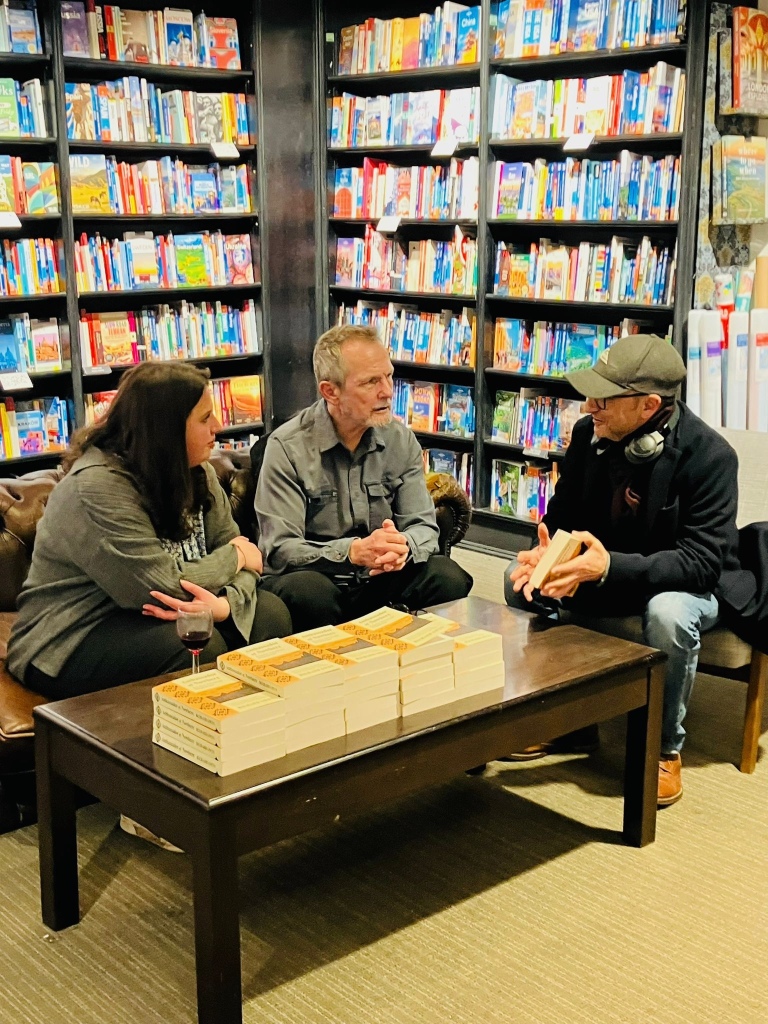

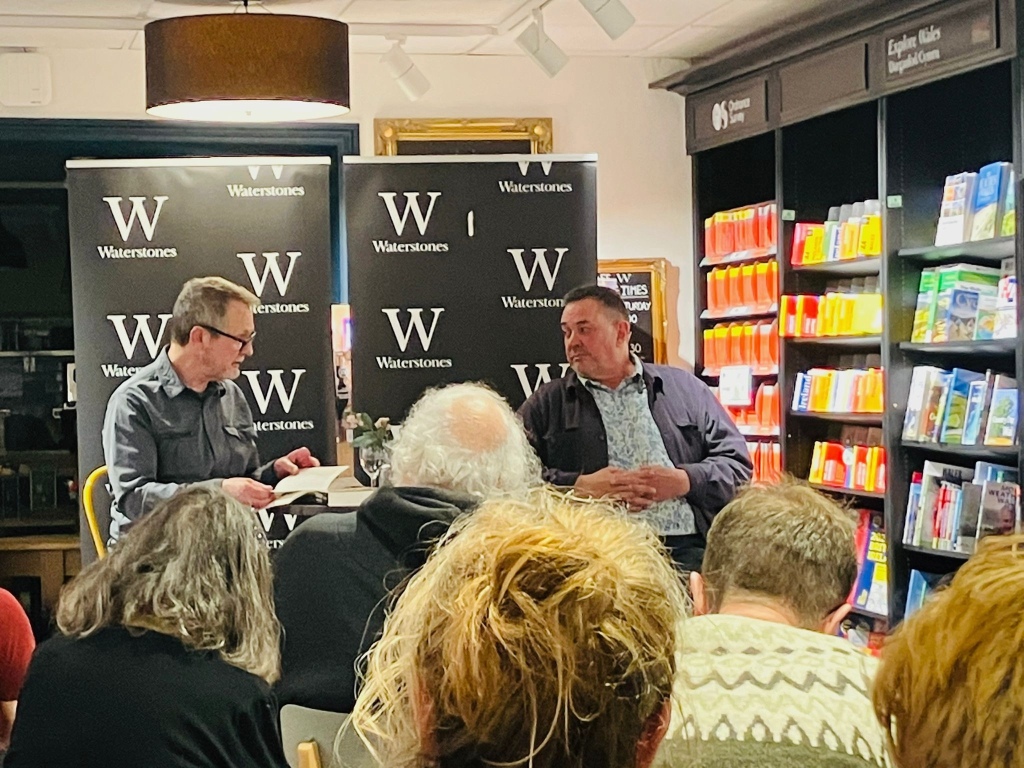

Last month I was interviewed by the excellent Gary Raymond for his BBC Radio Wales Arts Show (listen here) and last week we did a Q&A in anticipation of our chat at the Abergavenny Writing Festival tomorrow. For more on Gary’s writing, please check out his Substack publication, Blue, Red and Grey.

Richard Gwyn’s latest book is a book about the writing of a book, or rather a book about the research for that book, the award-winning The Other Tiger: Recent Poetry from Latin America (which incidentally, was my Welsh book of the year in 2016). Ambassador of Nowhere is a wild and searching ride through several Latin American countries, an in-depth look at cultures and literary movements, as well as political backdrops, full of drinking, poets, and death. What more could you ask for?

I had Richard on the Radio Wales Arts Show a few weeks back to talk about the book, but fortunately, the ever-truncated opportunities for discussion natural to the radio format will be widened on April 19th, as I get to talk to Richard at greater length at the Abergavenny Writing Festival. Details can be found here.

In the meantime, Richard has agreed to engage with my writers’ QnA.

Where are you from and how does it influence your work?

I grew up in Crickhowell and the landscape of the Black Mountains still holds an almost mystical fascination for me. That is my Cynefin, to which I belong and will always return. It’s also near the border, and borders have been a zone of interest to me throughout my life (I once swam across the Evros, the river that forms the border between Turkey and Greece, because my friend and travelling companion, an ‘illegal’ north African migrant, didn’t have papers). On the other hand (and there is always another hand) I am a committed European and internationalist and while I support Welsh independence, I detest provincial or parochial thinking.

Where are you while you answer these questions, and what can you see when you look up from the page/screen?

I am in my attic in Grangetown, Cardiff, with a vista from the loft window of three gigantic tower blocks emerging on the other side of the Taff that will soon dwarf all around them, and block the morning sun from view. Right now my attic space is covered with boxes of books, pots and pans, camping gear, kids’ clothes, a menagerie of cuddly toys, the debris of 30 years living and raising a family in this house. My wife and I are in the process of selling up and moving home, closer to my place of origin (see Q. 1)

What motivates you to create?

No idea, but I can’t imagine not doing it. I like the way that Lydia Davis puts it, when she says that travel, writing and translation are all inextricably linked. That works for me.

What are you currently working on?

I have recently finished a book about the Welsh landscape artist James Dickson Innes (1887-1914) and am now working on a book of perambulations around the Black Mountains (see Q.1)

Writers are always a couple of years ahead of their readers, so a book like Ambassador of Nowhere, which has just been published, was actually finished in 2022. Sometimes it is an effort to remember who you were (or who you thought you were) when you wrote the book that for everyone else is your latest thing.

When do you work?

Very early morning, and for as long as I feel like it — usually no more than three or four hours. It’s a habit I got into when I had a full time job and it works for me.

How important is collaboration to you?

Since I also work as a translator (from Spanish) collaboration is a constant. When I am working on my own stuff, I am accompanied always by my double, or doppelgänger.

Who has had the biggest impact on your work?

As a teenager I was a fanatical reader of the Russian classics (in translation) but probably the turning point came when I discovered the Argentine Jorge Luis Borges as an 18 year old, followed closely by the Italian fabulist Italo Calvino. I have always read widely in other literatures, and having lived in both Greece and Spain for long periods I was influenced in turn by the modern Greek poets, Cavafy, Seferis and Ritsos — and later by a raft of Spanish-language novelists and poets, many of them Latin Americans. I would count Montaigne as an abiding influence, and also perhaps Joan Didion and John Berger. I like to think that the books we haven’t read are always there for us, like an invisible thread leading to places we might one day visit. Reading remains one of life’s great pleasures. But it needs to remain a pleasure, rather than a duty.

How would you describe your oeuvre?

No doubt living in other countries for much of my twenties and thirties set me at a distance from many Welsh authors. I think that has definitely left a mark on the way I regard both my writing and my native country. Since I seem to be writing more about Wales these days, I am curious to see how this will pan out. Ever since reading Raymond Williams’ uncompleted Black Mountains trilogy, I always wanted to complete one of my own. Just to make things difficult for myself, I now envisage my 2019 novel, The Blue Tent, set in the Ewyas valley, as the middle part of that trilogy, rather than the first, as I originally thought, so I now have to write a prequel and a sequel. But I have a pretty good idea of what they are about.

What was the first book you remember reading?

In its entirety? Five go off to Camp, by Enid Blyton. I was maybe six years old.

What was the last book you read?

Wish I was here, a memoir by M. John Harrison. I’m still reading it, and am yet to make up my mind about it. It’s the kind of book that needs time to settle.

Is there a painting/sculpture you struggle to turn away from?

The one on our living room wall. It’s by the Catalan artist Lluis Peñaranda, a dear friend, who died in 2010, far too early. It shows four figures carrying a huge fish.

Who is the musical artist you know you can always return to?

JS Bach and Leonard Cohen.

During the working process of your last work, in those quiet moments, who was closest to your thoughts?

James Dickson Innes. Who is the book’s subject, fortunately.

Do you believe in God?

After a fashion.

Do you believe in the power of art to change society?

No. Or rather, I believe in the power of art to shape ideas, and therefore, to a limited degree, influence trends within society. But fascistic, retrogressive thinking is far more likely to prevail, because most people seem to prefer the certainties of bigotry and prejudice that attach to such a mindset: hence Brexit, hence Trump. I don’t believe in the idea of progress, certainly not in terms of humankind’s capacity for ignorance and cruelty.

Which artist working in your area, alive and working today, do you most admire and why?

If you had asked me this a couple of years ago I would have said the Spanish novelist Javier Marías, but he died in 2022, following complications from Covid. Apart from being an extraordinarily incisive writer (who saw the novelist’s craft as akin to that of the spy) he was also a dedicated enemy of hypocrisy and bullshit. He spent a lifetime pissing people off, which is almost always admirable.

But since Marías doesn’t count, I will go for the Mexican writer Juan Villoro. He is not widely read over here but is considered a major figure in Latin America. I’d especially recommend his novel The Reef, and his astonishing book about Mexico City, Horizontal Vertigo. He has spoken out bravely against the persecution of journalists in a country ravaged by criminal cartels and political and police corruption. His scope and vision are extraordinary and he has also played a significant but discreet role in movements for social justice (his father, Luis Villoro, was an influential figure behind the Zapatista movement of the 1990s).

What is your relationship with social media?

One of dread. I find it useful, up to a point, but am terrified of my own potential for time-wasting.

What has been/is your greatest challenge as an artist?

Getting and staying sober (see next question)

Do you have any words of advice for your younger self?

For much of my earlier life I had serious addiction issues, and although I was constantly filling out notebooks, I wrote nothing of any consequence, so the first thing I’d advise myself would be not to drink quite so much. Since that advice would obviously go unheeded, I’d suggest meditation and a long stretch of solitude on a remote island, preferably uninhabited.

What does the future hold for you?

I am no longer young (or anything near it) so will most likely miss the full consequences of climate catastrophe. But each of us will, necessarily, find our own ways of coming to terms with that, and in the meantime, I have a few more things I’d like to write, and a few long walks to do, alone and in company.

Ambassador of Nowhere is out now.

Blue, Red and Grey is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Gary Raymond is a novelist, author, playwright, critic, and broadcaster. In 2012, he co-founded Wales Arts Review, was its editor for ten years. His latest book, Abandon All Hope: A Personal Journey Through the History of Welsh Literature is available for pre-order and is out in May 2024 with Calon Books.