The Cure, ‘Killing an Arab’, and The Others

Sometimes the past just won’t leave you alone.

When I lived in London – a long, long time ago – I went to a lot of gigs and occasionally had walk-on roles as a ‘poet’ with bands at insalubrious venues in the punk and immediate post-punk era. My most stellar performance took place alongside The Cure at a gig in Walthamstow. I don’t have a clear memory of the circumstances – in those days most social interactions took place in a frantic haze of amphetamines and alcohol – and so I am unclear now whether the things that I remember are the things that actually took place, or whether some other version of events has taken their place, perhaps a version enacted or modified by the person I refer to as my Other, who has been responsible for many of the things I would rather not remember over the years.

Because I foolishly mentioned it in a blurb when I was short of ideas, the ‘Cure gig’ has become a recurrent incident about which I am required to give an account at various events in different places in the world where, for reasons quite beyond my understanding, I happen to be interviewed by a Cure fan. This morning was possibly the worst example yet.

I was introduced to the sound of ‘Killing an Arab’ pounding over the speakers, in front of over a hundred Colombian schoolchildren, who, I was almost certain, would have no idea who The Cure were, and a few jaded poets of my own generation, who probably did. I was then asked to give an account of what happened that fateful night in 1980 when somebody introduced me to Robert Smith, and I ended up on stage spouting all kinds of drivel dressed up as performance poetry (and was, I seem to recall, asked back by Mr Smith to do another set).

I then have to talk to the kids about How to Be a Writer. I am in the process of delivering my usual reply, of reading a lot and learning to lie with impunity, when it occurs to me that the whole Cure story might just as well be a lie. Did I in fact make this story up? Perhaps it would be easier to claim that I have, and then I wouldn’t need to recount what happened when I can’t really remember. I could just say Sorry guys, that was just a lie. I made it up. Or else I could recount it anyway, on the understanding that what I was saying was not necessarily the truth; that these things happened, but happened to my Other.

However, after the event, these beautifully turned out and well-behaved Colombian school kids, to whom I assumed I was talking of matters as remote as The Magna Carta, turned out to know as much about the British punk scene of the late 1970s as I do (or can remember). Did I know the Sex Pistols? How about The Clash? Was I friends with Johnny Rotten? Johnny, I tell them, makes commercials for a popular brand of butter these days. They seem a little bewildered by this reply.

Which brings me to the post of two days ago: ¿Donde están los otros? ‘Where are the others?’ I have a feeling this graffiti is going to pursue me for the duration of my Colombian trip. And I wonder if there is another wall, in a parallel Bogotá, in which the others have written an identical message, referring of course to the ones who put the graffiti there in the first place, making them the others’ others.

And as I watch the TV after the reading, with its footage of mass shootings in Iraq, I begin to imagine how this question, ‘Where are the others?’ could keep recurring in an infinite series of parallel Bogotás, to the soundtrack of The Cure playing a song with a horribly contemporary title.

Deconstructing the Wise Old Man

Lord, protect us from the wise old men of literature

Though in fact, the Lord may be the last person to do this protecting. At the literary festival I am currently attending, and at every such conference or festival I have attended to date in various parts of the world there has been a celebration of some great writer, living or dead. All, with a single exception, have been men.

Last night, a Mexican poet was celebrated here in Bogotá. During the sycophantic introduction to this venerable and ancient poet, I was alarmed to be told that he was responsible for one of ‘the three great works of misogyny’ of the 20th century.

How can it be acceptable to make a statement of that kind, especially in the context of a society like Mexico, in which violence against women is of epidemic proportions? (You do not need to have ploughed through Bolaño’s 2666 to be aware of this fact, although it helps). How can it be acceptable for educated men to make jokes about this, and to laugh amongst themselves, as they did at the event last night? Would it be OK to laugh at an announcement that such and such a book was one of the ‘great racist novels of the twentieth century’? And yet somehow, in too many places, it is perfectly OK to derogate women in a way that would be considered unacceptable if a similar derogatory comment were directed at people of another race or colour.

And here is where we get to the ‘maestro’, the great man of literature, whose sonorous tones must be heard, whose opinions must be listened to, even if those opinions are self-regarding pap and without conceivable value. It is one of the dangers associated with the prestige given to writers in certain societies, as compared, say, with Great Britain, where no one gives a toss what writers think, and where the prestige of the poet is somewhere on a par with that of a refuse collector – but well beneath that of a pest control operative.

European writers might at first be impressed or flattered by the respect afforded writers elsewhere, and the bowing and scraping that goes on in the presence of so-called ‘great’ writers, especially old ones, however decrepit, lecherous or boring they might be. However, the problem is that the stereotype of the wise old man is, to put it crudely, a bit of a bollocks.

The fact of the matter is that many people simply get stupider as they get older; their prejudices atrophy, their most disagreeable characteristics come to the forefront, and they are only interested in talking (or hearing) about themselves.

Murder Bear

I dreamed last night that American intelligence operatives were investigating the poet WN Herbert, allegedly because, according to dream-logic, he was responsible for – dream quotation marks – ‘blocking up areas of cyberspace that the US security forces deemed particularly sensitive’. In the dream a homeland security spokesman announced on television that the subversive Prof was under suspicion because his online activity was in danger of provoking a conflict with Russia. Bill was in trouble. I decided I had better call him, although I can hardly imagine he would need warning when the CIA had already made such a meal of announcing their investigation on TV. And besides, according to the previous day’s FB posts, Bill was in Crete: would he have signal there? And his phone was bound to be bugged. Perhaps I had better email. Same problem. Poor Bill. What would he do? What could I do to help?

On waking, I wonder where this particular dream has come from. I suspect it may relate to Murder Bear, Herbert’s horrifying ursine trope, perhaps interpreted by the spooks as a code matrix relating to Russian mobilisation on the Ukrainian border. But more likely, on reflection, would be Dogbot Borstal. This bizarre online association, or secret society, clearly harbours individuals of dangerously paranoid leanings, such as Goat Dog, Dumbo Octopus, and other cyphers.

Eduardo Halfon’s Monasterio and those salacious Romans

The problem with reading so many books at a time, so many, indeed, that the piles beside the bedside totter and sway; the problem, I think to myself in one of those everyday moments of realisation that seem to link up everything in the universe in a sublime act of synthesis, is that the themes, the plots, the characters, all start to form a single continuous entity, and one’s reading begins to resemble the world, infinite in association and connotation . . .

Reading Eduardo Halfon’s sublimely nuanced new offering, the novella – for want of a better word – Monasterio, I am struck once again by the simple fluency of Halfon’s prose, indeed slightly envious that he carries off acts of complex suggestivity with such grace and clarity of expression. I do not wish to get bogged down in a fallacious argument about the meaning of ‘clarity’ or ‘simplicity’ in prose writing: readers of Spanish will already have the opportunity to sample what I mean, and the author’s growing legion of English readers have a real treat to look forward to when the book appears in that language. The story follows Eduardo Halfon, a cypher, or perhaps a version, of Eduardo Halfon, but one who smokes a lot of cigarettes, whereas the real Halfon ‘seldom smokes’ (as my uncle once remarked to a German parachute officer surrendering to him at Monte Cassino, while simultaneously offering him a fat cigar). Not smoking is not the only difference between Eduardo and Eduardo, but let’s not confuse perception and representation. For a long time I thought this particular author was magnificently moustachioed, whereas in reality it is the way his little finger nestles to the side of his mouth on the sleeve photo of his books . . . but let’s move on . . .

The book begins with Eduardo and his brother arriving at Tel Aviv airport to attend the wedding of their sister, who has joined a fundamentalist Zionist group and is due to be married off to a fellow fanatic selected for her by the Rabbi. It is hot and our protagonists are not in the best of moods. Neither of them are practising Jews and they have serious reservations, to say the least, about both their sister’s faith and her prospective spouse, whom none of the family has met. A man who was on the flight with them, and is waiting by the carrousel, is suddenly set upon by security and bundled away. It happens in an instant. Eduardo thinks he recognises one of the Lufthansa flight attendants near the man as an ex-flame, Tamara, but he is not certain . . . Within the seven opening pages the essential matrix of the story is laid out. But the mastery of Halfon’s style lies in the way the story unfolds. He takes his time. There is nothing wasted in his prose. Everything counts, and everything holds our attention.

Late in the book (it is only 120 pages, but its density makes it seem longer) we go for a dip in the Dead Sea, and there is an extended discussion on the theme of salt. One of the most interesting nuggets to come out of this passage is that “the Romans called a man in love ‘salax’, which means to be in a salty state, and which is . . . . the origin of the word salacious.”

A salty dog, anyone?

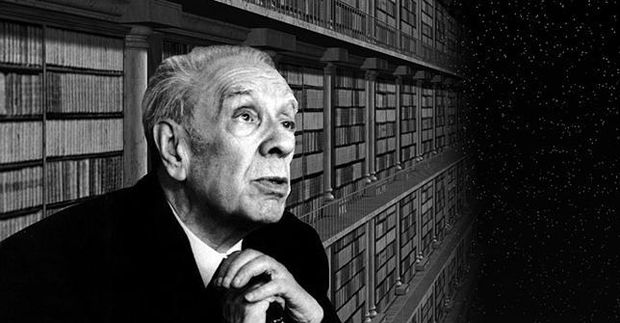

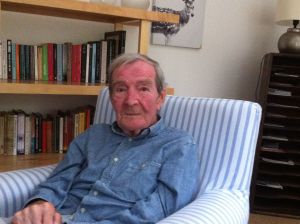

Fictions and Foreigners: Borges and Alastair Reid

The first story I read by Borges, at the age of eighteen, was Tlön, Uqbar, Tertius Orbis. Although the name would have meant nothing to me at the time, the translation was by Alastair Reid. Forty years later, I get to meet the man, now 88 years of age, a little frayed around the edges, but alert and bright eyed as a moorland bird. He lives in New York but spends part of every summer in the Dumfries and Galloway region where he was born and raised. I have been advised that Alastair would prove an invaluable repository of experiences and anecdotes for my researches into Latin American literature, concerning, among others, Borges, Neruda and Gabriel García Márquez, all of whom he knew well – Borges, best of all. And so it was that one bright July morning I set out with my friend Tom Pow across the Dumfries countryside towards our rendezvous.

I have yet to transcribe the recording, but two things stood out in our conversation. Neither of them will be surprising to those who are familiar with the work of Borges, but they are fascinating to me nonetheless.

Translating Borges was, according to Alastair Reid, at times like re-translating something that had originally been written in English, and subsequently translated into Spanish. This, apparently, was due to Borges’ own familiarity and long use of the English language (he had an English grandmother, was brought up bilingual, and learned to read in English at an early age). The task of the translator, then, felt like rendering the story back into its original language, which Alastair described as a somewhat unsettling or daunting experience, and quite unlike translating other Spanish language writers.

The other thing that stood out for me in our talk was Alastair’s insistence that for Borges everything was a ficción, a fiction. As he puts it in his essay ‘Fictions’ (in the wonderful collection Outside In): ‘Borges referred to all his writings – essays, stories, poems, reviews – as fictions. He never propounded any particular theory of fictions, yet it is the key to his particular lucid, keen, and ironic view of existence.’ I was dimly aware of this, but not to the extent that this infiltrated his approach to literature and the world. In his essay, Alastair Reid elaborates:

A fiction is any construct of language – a story, an explanation, a plan, a theory, a dogma – that gives a certain shape to reality.

Reality, that which is beyond language, functions by mainly indecipherable laws, which we do not understand, and over which we have limited control. To give some form to reality, we bring into being a variety of fictions.

A fiction, it is understood, can never be true, since the nature of language is utterly different from the nature of reality.

And so on.

Alastair Reid’s essays contain so many observations and aperçus about the writers he has worked with (the 1976 essay ‘Basilisk’s Eggs’ is another gem) it would do them little justice to summarize. And that is only half the story: some of Reid’s most impressive writing concerns his own reflections on travel and identity: on the one side his Scottish beginnings, or ‘roots’ (a word he treats with caution), on the other the years of wandering. Perhaps my favourite is ‘Notes on being a Foreigner’ in which the author makes astute and (to my mind) accurate observations on that state or condition – one that a person is probably born to – as opposed to, say, a tourist or an expatriate.

‘Tourists are to foreigners as occasional tipplers are to alcoholics – they take strangeness and alienation in small, exciting doses, and besides, they are well fortified against loneliness . . .

. . . An expatriate shifts uncomfortably, because he still retains, at the back of his mind, the awareness that he has a true country, more real to him than any other he happens to have selected. Thus he is only at ease with other expatriates . . .

. . . The foreigner’s involvement is with where he is. He has no other home. There is no secret landscape claiming him, no roots tugging at him. He is, if you like, properly lost, and so in a position to rediscover the world, form outside in.’

As for being ‘properly lost’ – this is a theme to be continued ( if I make it back to Wales).

A Journey into Memory

When I remember things from childhood or early adulthood, it often feels as though I am a passive subject, a receptacle or vessel, and the process of remembering becomes one in which memory is seeking me out, digging its way into my sense-making apparatus, rather than there being any sort of ‘I’ trying to make sense of the things remembered.

I am all too aware that as far as memories are concerned, it is the act of construction (more accurately reconstruction) that matters, of making the bits fit our self-narrativisation. In other words, as Gabriel García Márquez put it: ‘Life is not what one lived, but what one remembers and how one remembers it in order to recount it.’

In his memoir, Other People’s Countries (subtitled A Journey into Memory), Patrick McGuinness asks fascinating questions about the way that identity is rooted in memory, more specifically in the way that we remember. “Trying to remember is itself a shock, a kind of detonation in the shadows, like dropping a stone into silt at the bottom of a pond: the water that had seemed clear is now turbid (that’s the first time I’ve ever used that word) and enswirled.” On reading this passage, which comes on Page 7 of the book, I found it noteworthy that McGuinness comments on the fact that he has not used the word ‘turbid’ before, which immediately casts suspicion on the observation, because one wonders whether, by commenting on memory’s cloudiness and turbidity, he has merely dislodged an existing memory, and is therefore, perhaps, not ‘using the word for the first time’ at all. And how telling that his use of the word ‘turbid’, and his comment on that usage, should immediately be followed by a neologism, ‘enswirled’.

In his memoir, Other People’s Countries (subtitled A Journey into Memory), Patrick McGuinness asks fascinating questions about the way that identity is rooted in memory, more specifically in the way that we remember. “Trying to remember is itself a shock, a kind of detonation in the shadows, like dropping a stone into silt at the bottom of a pond: the water that had seemed clear is now turbid (that’s the first time I’ve ever used that word) and enswirled.” On reading this passage, which comes on Page 7 of the book, I found it noteworthy that McGuinness comments on the fact that he has not used the word ‘turbid’ before, which immediately casts suspicion on the observation, because one wonders whether, by commenting on memory’s cloudiness and turbidity, he has merely dislodged an existing memory, and is therefore, perhaps, not ‘using the word for the first time’ at all. And how telling that his use of the word ‘turbid’, and his comment on that usage, should immediately be followed by a neologism, ‘enswirled’.

These are nice illustrations of the way that language, our use of it, and its use of us, can be an element in the process of remembering. I am thinking in particular of those laden words which, when they crop up, immediately bring with them a sequence of memories and associations. I remember reading somewhere that our memory of language is the best reason why one should not translate into a language that is not our mother tongue. Words carry their own baggage with them: when you hear certain words, they spark off a whole sequence of associative meanings and memories, stretching back to childhood, that would simply not be available to an individual who has learned a language as an adult.

Childhood is the source of many of these word-memories. Like smells or taste (Proust’s oft-cited madeleine), words, long forgotten or unused, are capable of eliciting entire submerged worlds. But is it the memory of the word itself that achieves this, or the memory of a memory? As McGuinness speculates:

‘And as with so much of that childhood, I seem to remember not the things themselves but the memories of the things, as if the present I experienced them in was already slowing up and treacling over, fixing itself in a sepia wash.’

There are so many good things in this book, things that make you reach for a pencil, or else just stop in your tracks and reflect about the words you have just read. You can dip in, pick a page at random, and come out with some crystallized memory, or some jewel of detailed observation.

Other People’s Countries is, on one level, about a house in Bouillon, in the Ardennes region of Belgium. The house belonged to McGuinness’ family (his mother was Belgian) and was the author’s own childhood home. The book is divided into many short chapters: in this way they resemble the rooms of a large house, perhaps Quintilian’s House of Memory. I’ll conclude with one of my favourite chapters, titled ‘Keys’, which follows in its entirety:

‘Watching an old police procedural, probably a Maigret, sometime in the early eighties while convalescing from glandular fever (an illness I experienced more as convalescence than as actual illness: I felt as if I was simply recovering from something, rather than actually having the something to recover from in the first place), it came to me: a thief pushing a key into putty so that it’s outline would be caught in the relief and he could copy it, then burgle the house.

That was memory, I realised: a putty with which you make another key, which would open the same door, but never quite as well. In no time, you’d be burgling your own past with the slightly off-key key that always got you in though there was less and less to take.’

The last digression of Patrick Leigh Fermor

Reading the final ‘long awaited’ – which in this instance meant waiting for the Death of the Author in 2011 at the age of 96 – third volume of Patrick Leigh Fermor’s account of his 1934 trek across Europe, three questions occur to me about the inability of PLF to complete and publish the book while still alive.

1) the accumulation of digressions (both of writing and in life); indeed what amounted to PLF’s compulsion to digress (of itself no bad thing);

2) his failure of memory, aided and abetted by the loss of certain of the relevant notebooks;

3) an inability to contemplate the end of his journey which must, by some not-so-strange interior logic, also mean the end of his life.

An article by Daniel Mendelsohn in the current issue of The New York Review of Books also suggests a combination of factors, most particularly the digressions that formed such a substantial part of Paddy’s life and work. “We shall never get to Constantinople like this,” the author announces in a meta-textual aside, which constitutes “a humorous acknowledgement . . of a helpless penchant for digressions literal and figurative . . .”

Indeed, “the author’s chattiness, his inexhaustible willingness to be distracted, his susceptibility to detours geographical, intellectual, aesthetic, and occasionally amorous constitute, if anything, an essential and self-conscious component of the style that has won him such an avid following.”

The naivety and sheer joy of unfettered travel; the “ecstasy” that Paddy describes on “realising that nobody in the world knew where he was” – a sensation, as Mendelssohn points out, that would be practically impossible for travellers today, but which I recall from my own wanderings in the 1980s as having provoked a similarly feverish sense of total liberation; the wonderful lists that pepper his writing, eliciting new tastes and new sensations and a constant hunger to celebrate life as fully as possible; his unerring ability to stir in the reader a desire to write – which to me constitutes a failsafe criterion of all good writing; and finally – almost because of its flaws – and certainly because of what we know to have transpired in the two earlier volumes, and the unbearable anticipation of the thing – which was like a Sword of Damocles for PLF in later years – all of these help to make this book one of the most enjoyable reading experiences of the year thus far. While reading it too, I am more conscious than I was during the preceding two volumes of Paddy’s tendency to confabulate. At more than one point Paddy confesses that he cannot truly remember what happened next, but continues anyway, and even interjects passages of outrageous fantasy to spice up the story. A quotation from Javier Marías’ novel, The Infatuations, comes to mind:

“Everything becomes a story and ends up drifting about in the same sphere, and then it’s hard to differentiate between what really happened and what is pure invention. Everything becomes a narrative and sounds fictitious even if it’s true.”

Like Mendelsohn, I found The Broken Road’s incompleteness, paradoxically, to be more fitting than any neatly circumscribed ending that the author might have engineered. After so much deep description, after so many early mornings waking by the roadside with a sense of the sheer limitless possibility of the unfinished journey, after so much continuous pointless peregrination, any kind of ‘arrival’ would only have been a let-down.

While listing, above, the three reasons for the unfinished nature of the trilogy, a fourth, not entirely facetious option came to mind. Paddy famously never referred to the ultimate destination of his journey as Istanbul, but as Constantinople. Since ‘Constantinople’ did not exist under that name (nor had it, strictly speaking, since 1453), Paddy was never going to arrive. Instead we are allowed to share with him the nostalgia (which he shares with Cavafy) for a broken Hellenic world, for the ghosts of Byzantium, and a burgeoning sense of the terror that was about to descend on Europe in the years immediately following his journey.

The Pig of Babel

Saltillo has proved the most hospitable and generous city I have visited in Mexico. It seems to be filled with people who love books and actually read them, in spite of being the centre for Mexico’s automobile industry. Yesterday the temperature soared to 38 degrees by midday and my hosts Monica and Julián put on an asado – the Latin version of a barbecue – and many of the people who attended our reading on Saturday night at the wonderfully named Cerdo de Babel (Pig of Babel) turned up. The Pig of Babel, incidentally, for anyone who intends travelling in northern Mexico, is officially Blanco’s favourite bar, seamlessly marrying the themes of Pork and Borges, and taking over from Nick Davidson’s now defunct Promised Land as the most congenial hostelry in the Western Hemisphere (although I realise such a term is entirely relative and depends on where you are standing at any given moment).

The culture section for the state of Coahuila produced a beautifully designed pamphlet of five of my poems, for which I have to thank Jorge and Miquel. I would also like to offer my thanks Mercedes Luna Fuentes, who read the Spanish versions of my poems in Jorge Fondebrider’s fine translation, and Monica and Julián for the use of their and Lourdes’ home – especially since Julián had to endure my garbled Spanish explanation of the rules of Rugby Union last night, which may well have been a bewildering experience for a Mexican poet, but which I considered an essential duty of a Welsh creative ambassador.

On a different theme entirely, the fifth issue of that very fine magazine The Harlequin is now online, and it contains three new poems by my alias, Richard Gwyn, including this one, reflecting on an entirely different – but inevitably similar – journey to the one currently being undertaking.

From Naxos to Paros

Of the journey from Naxos to Paros

all he could remember

were the lights of one harbour

disappearing into the black sea

and the lights of another

emerging from the same black sea

and he thought for a moment

that all journeys were like this

but that many were longer.

Popocatépetl

Yesterday I came back into Mexico City from Puebla, the massive form of Popocatépetl (5,426 metres) to my left – caught fuzzily on my phone camera – passing the misty woodlands and broad meadows that gather around its base. It impressed on me the extraordinary diversity of the Mexican landscape, that within a few hours one can pass through prairie, forest and the high sierra. The only constant is the truly terrible music being played full volume wherever you go, including on this bus.

On Monday night in Puebla, as I was walking back to my hotel, an indigenous woman, utterly bedraggled, with long grey hair and in filthy clothes came running past me, apparently chasing after a big 4×4, crying out, at volume and with some distress ‘Don Roberto, Don Roberto . . .’ She carried on at pace up the street (Don Robé . . . Don Robé . . . ) for an entire block, and I could see the vehicle turning at the next set of lights. When I got to the junction, she had stopped, and was resting, hands on knees, her crevassed face fallen into a kind of resigned torment. She seemed elderly, although poverty and struggle probably accounted for an additional twenty years. I can hardly imagine what her story was – or the cruel, uncaring Don Roberto’s – but it was timeless, and seemed to sum up, more than any social analysis, the discrepancy between want and privilege, the honorific ‘Don’, gasped out as her spindly legs carried her in desperate pursuit at once implying his status and her subjugation. The image has stayed with me.

I returned to the city yesterday evening to attend a tertulia, a cross between a poetry discussion group and a workshop organised by the poet and short story writer Fabio Morábito and friends, where I was invited to read. Afterwards I visited the barrio of Mixcoac with Pedro Serrano and Carlos López Beltrán, passing by Octavio Paz’s family home, before returning to the more familiar confines of Condesa and supper at Luigi’s.

But today, back on the bus, the perennial Mexican bus. The clock at the front says 7.05. It is 12.50, but who cares? We pass through the sprawling shanty outskirts of southern Mexico City and back into the mist. Daily travel awakens in the traveller a kind of constant dislocation, which is not surprising considering the word means just that – a state of being displaced, an absence of locus. I never believed, as some of my generation seemed to, that travelling of itself was a kind of means of discovering oneself. I have absolutely no interest in discovering myself, nor anybody else for that matter. But I am drawn to Cuernavaca, not only for its alleged beauty, for the fact that it lies Under the Volcano and is the setting for Malcolm Lowry’s magnificent novel of that name, but in part at least because my late friend, Petros Prasinaki, aka Igbar Zoff, aka Peter Green came here sometime in the mid to late 197os in order to spend his inheritance, search for Lowry’s ghost and drink mescal, an example I will not be following. But I have a copy of Under the Volcano with me, just in case.

Will Self and the ghouls of literature

Like most people with an interest in the subject, I read Will Self’s article in last Saturday’s Guardian on the Death of the Novel with a strong sense of déja vu. The novel has ‘died’ so many times already it must be truly sick and tired of being dead. Following the Washington Post’s recent revelation that poetry is dead also, should we be concerned?

Readers of Blanco’s Blog will be familiar with the writer’s various tussles with the novel, not simply the discomfort imposed on the reader by having to wade through so much baggy stuff in order to consume the kernel, so to speak – if there is one – but also the demands made on the author in struggling to keep the damn thing fresh and alive, when it should just lie down and die.

Will Self’s argument, fluently expressed – although, as usual, not only hyperbolic, but perhaps a tad Thesaurus-retentive (e.g. Most of it is at once Panglossian and melioristic) – moves towards its expected conclusion with unerring certitude: the novel is dead; long live the novel:

The form should have been laid to rest at about the time of Finnegans Wake, but in fact it has continued to stalk the corridors of our minds for a further three-quarters of a century. Many fine novels have been written during this period, but I would contend that these were, taking the long view, zombie novels, instances of an undead art form that yet wouldn’t lie down.

Insistence on the death of the novel (never mind of its author) was once answered quite superbly by a character in Don Delillo’s The Names (my favourite of his), who expresses the idea of the novel’s zombiehood thus, and I cannot think of a greater or more delicious challenge to any would-be novelist:

“If were a writer,” Owen said, “how I would enjoy being told the novel is dead. How liberating, to work in the margins, outside a central perception. You are the ghoul of literature. Lovely.”

Jaguars, snakes, rabbits

If you travel, Blanco thinks, if you just travel, go from place to place, walk around, you should never get bored and you should never lack for things to do or write about, if this happens to be your thing. At least that is the theory. Blanco has a minor epiphany: he must go to Coatepec (the accent is on the at): it fulfils the single major criterion he has always employed when deciding whether or not to visit a place: he likes the sound of it; it carries the resonance of something remote – in time and culture – and yet somehow reassuring. He is walking down the hill from the Xalapa museum of anthropology, and after an entire morning within its confines he has become saturated with Olmec images of human figures and jaguars and serpents, and he flags down a taxi driven by a man with stupendously fleshy earlobes; earlobes that remind him of small whoopee cushions or rolled dough or moulded plasticine. The taxi driver chats about corruption in Mexican politics. It is raining. It has been raining all morning and all last night, and throughout the previous evening, and as far as we know it has never not been raining. Outside of Xalapa there is a roadblock. The young policeman carries an automatic rifle and wears black body armour, leg armour, the works. He inspects the taxi-driver’s I.D. and stares at Blanco for several seconds. It continues to rain.

We arrive in Coataepec and get stuck in a traffic jam. Nothing moves. The taxi driver asks directions, but that doesn’t help the traffic move. Blanco spots an interesting-looking restaurant, pays the taxista, and gets out. The restaurant has a nice inner patio with a garden area, and tables around it, out of the rain. In the garden there are roses and other flowers. A large family group are finishing their meal and then spend at least twenty minutes taking photos of each other in every possible combination of individuals, so that no one has not been photographed with everybody else. They have commandeered the only waiter in order to help them in this task. Every time Blanco thinks they are about to leave and release the waiter they reconvene for a new set of photos. One of the men (a Mexican) has very little hair but a long grey ponytail, which cannot be right. One of the women – I suspect Ponytail’s sister – is married to a gringo, it would seem. He has long hair also, but not arranged in a ponytail. He speaks Spanish well, with a gringo accent. Blanco orders tortilla soup and starts leafing through a magazine he bought at the anthropology museum. His phone makes a noise that tells him he has received a message. It informs him, in Spanish: Health: Adults who sleep too little or too much in middle age are at risk of suffering memory loss, according to a recent study. He looks at the message in consternation. Too little or too much? So, hey– you’re bolloxed either way. Who sends this stuff? The screen says 2225. Then another one: Japanese fans of Godzilla were very upset with the news trailer of this film to find that Godzilla is very big and fat: read more! 3788. Then a link. Blanco shakes his head sadly.

Coatepec is full of interesting buildings with courtyards. Blanco heads down to the Posada de Coatepec, a nice hotel in the colonial style, and goes in for a coffee. A slim man with fine features, a neat little moustache, dressed in polo gear, greets him in a friendly fashion, and Blanco greets him back, once again under the impression that he has been mistaken for someone he is not. A blonde woman, also in white jodhpurs, follows the man. There must have been a polo match. How strange. The hotel offers a nice shady patio, but we don’t need shade, we just need to be out of the rain. Blanco sits on the terrace outside the hotel cafe and writes in his notebook. Before long, the man who was in riding gear comes and sits on the terrace also. Immediately three waiters attend him, bowing and scraping, one of them is even rubbing his hands together in anticipatory glee at the opportunity to serve this evidently Very Important Person. Mr Important takes off his sleeveless jacket, his gilet, and immediately one of the waiters – like a magician with a bunny – produces what appears to be a hat-stand for midgets, but is, presumably a coat-stand. Clearly the Important Person cannot do anything as vulgar as sling his coat over the back of a chair. Another waiter opens a can of diet coke at a very safe distance, and only then brings it to the table, along with a glass filled with ice. He is bending almost double, as if to ensure that his body doesn’t come into too close and offensive a proximity to the Important Person. It is one of the most extraordinary displays of deference I have witnessed in my life. Then all three waiters – the one who brought the coat-stand, the one with the coke, and the one who was rubbing his hands, a kind of maître d’ – vanish inside like happily whipped dogs. Left alone, the Important Person makes a phone call in a loud voice. He is barking instructions to some underling. He is clearly someone who is used to being obeyed, like an old school Caudillo. Must be a politician. When he has finished his call, he looks around and gets up to go inside the restaurant, where his company – family and friends, I guess – are seated. He walks inside with his drink, and within seconds one of the waiters appears out of nowhere, grabs the coat-stand, and follows him in with it.

We have to go. I have arranged to meet a poet back in Xalapa and discuss literary matters. He is called José Luis Rivas and has translated T.S. Eliot and Derek Walcott into Spanish.

Episodic Insomnia

Every night for a month he wakes at a fixed time between the hours of three and four, perplexed by the routes he took around the eastern Mediterranean years ago, following sea-tracks or mountain paths or those alleyways between tall decrepit buildings that hide or reveal a dome or minaret, glimpsing moments of a half-remembered journey. Or else he is mistaken, and it is not the journey that wakes him but the need to write about it, and his alarum is this hypnopompic camel, trotting over memory’s garbage tip: intransigent, determined. How is it that we reach that state in which the thing remembered merges with its remembering, the act of writing with the object of that need to tell and tell? And so he wakes again at a quarter to four, another dream-journey nudging him tetchily into wakefulness like a creature in search of its soul, and this time he is peering from a terrace on the milky heights at Gálata, or else gazing eastward from the battlements at Rhodes, and wondering whether he has always confused the journey with the writing of it, whether the two things have finally become one.