Feet

A taster from Mexican poet Pedro Serrano’s collection, Peatlands, translated by Anna Crowe and fresh off the press from Arc, who are to be congratulated, yet again, for bringing another fine writer to the attention of the English language reader.

There is also an introduction by W.N. Herbert, where we find these lines, which seem so apposite with regard to the poem I have chosen: “The intention [is] to transform us through language, compelling us to rethink, re-imagine and re-envision the world and our place in it; and to break down our unconsidered assumptions about opposed categories like thought and feeling, human and animal, by continually returning us to the matrix of the body . . .”

FEET

Feet clench, make themselves small, run away,

creasing their wretchedness and fear in lines

identical to those on our palms and different.

Feet are extensions of God

(which is why they are low down),

hence their distress, their rounded bulk, their lack of balance.

Feet are like startled crayfish.

Such vulnerable things, feet.

When they make love they clench and huddle together

as though they were their own subjects.

So feet are not made, then,

to cling, like wasps

to every pine-needle pin,

to every branch of the soul that makes them there.

They are more wings than feet,

tiny and fragile and human.

However much we overlook them.

LOS PIES

Los pies se doblan, empequeñecen, huyen,

curvan su miseria y su miedo en unas líneas

que son las de la mano y no lo son.

Los pies son extensiones de Dios

(por eso están abajo),

de allí su angustia, su volumen redondo, su desajuste.

Los pies son como crustáceos asustados.

Tan sensibles los pies.

Se doblan y apeñuscan al hacer el amor

como si ellos fueran sus sujetos.

Los pies, así, no están hechos ahora

para prenderse como avispas

a cada aguja,

a cada rama del alma que allí los haga.

Son más alas que pies,

chiquititos y frágiles y humanos.

Tan desconsiderados que los tenemos.

Of Dogs and Death

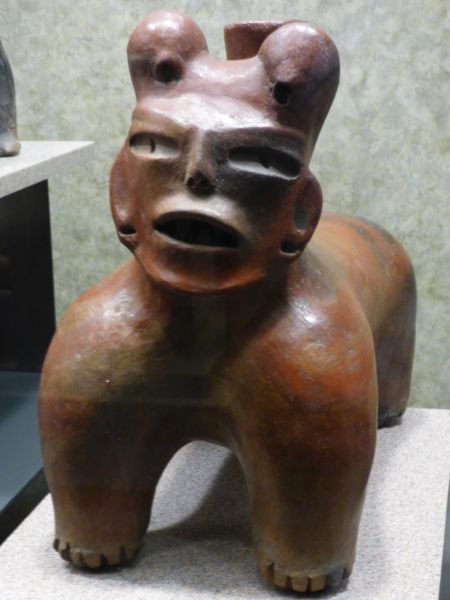

Dogs (such as this one, in the Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City) guided their people to the next world in Aztec culture.

I wrote once before about Juan Rulfo and his novel Pedro Paramo, which has unparalleled status in Mexican literature and was a major influence on the young Gabriel García Márquez on his arrival in Mexico City in 1961.

I recently spent an evening reading Juan Rulfo’s short stories El llano en llama (translated into English both as The Plain in Flames and The Burning Plain). The stories were written in the long wake of the Mexican revolution, which coincided with Rulfo’s own childhood in an orphanage in Jalisco where, he said later, he often saw corpses hanging from posts, and that he spent all his time reading, “because you couldn’t go out for fear of getting shot.” These stories lead the reader into a space of silence and mystery, where reality breaks down and we enter a world that might be the antechamber to the afterlife, if the afterlife you have in mind is bleak, featureless, devoid of anything that could pass as life at all. But there are ghosts, at least.

The rhythms of Rulfo’s prose remind me of what Octavio Paz wrote about his archetypal Mexican: “his language is full of reticences, of metaphors and allusions, of unfinished phrases, while his silence is full of tints, folds, thunderheads, sudden rainbows, indecipherable threats . . .” There are threats aplenty, but they are unformed, vaguely defined and usually at some distance from the place of narration – yet always getting closer. Events take place in a half-light, as characters stumble towards yet another failure, or else death.

In the first story in Rulfo’s collection, ‘They have given us land’, a group of four landless men trudge across an arid plain. They have been promised land by some government official, but the ground beneath them is dry, stony, utterly unsuitable for planting anything that might grow. There had been more than twenty in their group, and they had horses and rifles, but now there are only four, and they have nothing, apart from a hen, which one of them keeps hidden inside his coat. “After walking for so many hours without coming across even the shadow of a tree, even the seed of a tree, nor the root of anything, we heard the barking of dogs.”

In another story ‘Don’t you hear the dogs barking’, a man carries his adult son on his back to try and find a doctor in the town of Tonaya. The younger man is wounded. It is night-time and the old man cannot see where he is going. As the pair draw near to the town we learn through the father’s faltering monologue that his son is a thief and a murderer, and he is only carrying him out of respect for the boy’s dead mother.

In these two stories, the barking of dogs indicates the existence, if not of hope precisely, then of some form of life, of human dwellings at the very least. But perhaps that is a false reading. In Mesoamerican cultures dogs were considered to have the powers to guide the dead to a new life after death, which explains why dogs have frequently been found buried with people in pre-Columbian sites.

And of course, at the end of Malcolm Lowry’s masterpiece, Under the Volcano, a dead dog is thrown down the ravine after the dead body of the unfortunate consul.

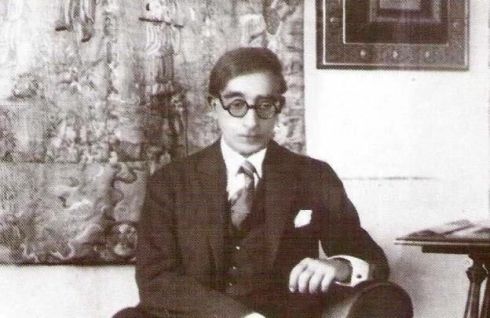

To come full circle, I discovered today that Rulfo had a bit-part in a Spanish film based on a short story by Gabriel García Márquez. The film is called En este pueblo no hay ladrones (In this town there are no thieves), and is exceptional in that the cast is made up of notable writers, visual artists and film directors, including Luis Buñuel (clearly relishing his performance as the town priest), Leonora Carrington, Arturo Ripstein, Alfonso Arao, Abel Quezada, and Gabriel García Márquez himself.

Juan Rulfo (left) and Abel Quezada having a beer, in a scene from ‘En este pueblo no hay ladrones’ based on a short story by Gabriel García Márquez.

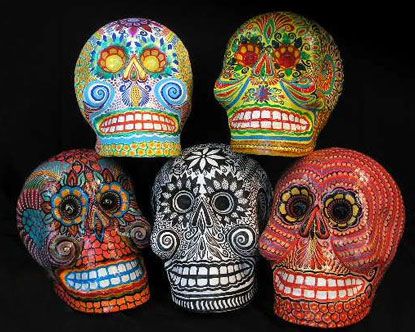

Masks and Death

When travelling, how do we begin to learn when someone is wearing a mask, with intent to deceive, given that we all wear masks much of the time?

We all know, as Hamlet says, that ‘one may smile, and smile, and be a villain’, and so I am thinking about how one goes about making judgements in another culture with people whose ideas about what qualifies as ‘sincerity’ is, perhaps, at a remove from one’s own culturally engendered version. And how, I wonder, do ‘I’ appear, the person who passes as myself (my own current person impersonator) with my own pretensions at ‘sincerity’, when for all my interlocutor knows, I am wearing a mask too, perhaps one more efficacious in design than his or her own.

These things trouble me. Should they? And how much does any of this matter, if, as Javier Marías reminds us in his novel The Infatuations (Los Enamoramientos), we are all novice ghosts: ‘whatever we do, we’ll only be waiting, like dead men on leave, as someone once said’.

A mask conceals, but to wear death on the outside conceals nothing, nada: it only reveals what we wear on the inside, what we carry inside us – our own eventual death – because we are ‘dead men on leave’ and one cannot conceal what can never be erased. So the mask of death, the grinning skull, is a double bluff, it is a way of anticipating our status as fragile ghosts, a way perhaps of trying to con or cheat or temporarily delay Death into thinking we are already dead, so he cannot choose us, he needn’t waste his time with us. This is not the same as the rather simplistic explanation I have read in tourist guides, namely that Mexicans like to display images of death and the skull in order to familiarise and trivialise it, to make it commonplace, to deny it real significance by flaunting it through macabre displays, even to the extent of eating chocolate skulls and skeletons. That, surely, would only constitute a bluff (a single bluff). And Death would not be fooled by that, surely?

How does a people – according to Claudio Lomnitz in his extraordinary book, Death and the Idea of Mexico – come to have death as its national icon? This question was addressed at length by Octavio Paz in his seminal study on the Mexican character, or what I am coming to think of as Mexicality, which manages to carry an almost-reference to mescal, the national liquor (usurped for many years by the Jalisco version, tequila, but making a fierce comeback among the middle classes, who previously eschewed it as a poor man’s drink). It is a view corroborated in Mexican culture by the prevalence of further imagery of death: not just in the ‘national icon’, as Lomnitz would have it, but in the extraordinarily graphic pictures (which would never be publishable in a UK newspaper) that accompany headlines of the latest narco-murder, and which, significantly, also accompany the paraphernalia of Christian death – exemplified by Christ’s death on the cross – here represented in a crucifixion scene I photographed yesterday in a Coyoacán church.

None of this will be new to anyone who knows anything at all about Mexico, but for me the whole symbology of death, celebrated so vividly in fiestas such as the Day of the Dead – well, all fiestas in fact, as the essence of a fiesta is to defy death, to celebrate a momentary explosion in time, thereby provoking an attraction of opposites: the fiesta beckons death by celebrating life with fanatical and joyous hubris – is a topic definitively at odds with our Western denial of death, our sterilising and alienating distancing of everyday life from any possible contact with the unspeakable void that death represents. But these are only preliminary thoughts on the topic, to which I may one day return.

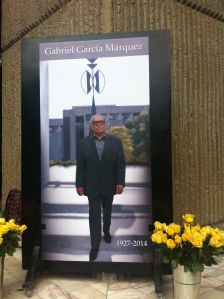

At the Festival of the Book and the Rose, which I attended yesterday, as a guest of the Periódico de Poesía, the celebrations were adjusted at the last minute to make way for an homage to Gabriel García Márquez, pictured below, on a placard, flanked by yellow roses. I also learned that the University (UNAM) is home to 325,000 students: the same population, give or take a few dozen, as the city of Cardiff.

With Ana Franco of the Periódico de Poesía and novelist and interlocutor par excellence, Jorge F. Hernández.

Inglaterra? Really? A tragic misallocation of nationality or a simplification for the geographically challenged?.

Mexican Masks: the ambassadorial posts

Day 1

What is a creative ambassador? According to the blurb from the Arts Council of Wales, ‘The Creative Wales Ambassadors Awards are made by nomination and recognise . . . individual achievement in the arts along with the aim to raise the profile of Welsh culture outside of Wales.’ My application was called Unfinished Journey and in it I wrote the following (forgive me reproducing this paragraph in full, but I thought it fair to present what I aim to do):

‘Modern journeys often awaken in the traveller a sense of ‘travelling without seeing’, an idea that is perhaps uniquely contemporary. The title suggests that rather than having a fixed point of departure and arrival, all travel is a continuum, and that the only valid objective is to sustain the exquisite tension of the unfinished journey. My project is to research and write an account of the process of travel as a work in progress. Reports will initially appear as journal entries, posted on the blog written by my alter ego, Ricardo Blanco, as we tour Latin America in search of its poets and its wanderers; but this will only be a part of the narrative, as the project will also take us through journeys past, as well as across a very personal Latin America of memory and the imagination. Unfinished Journey is linked to, but discrete from, preparation of my forthcoming anthology of Contemporary Latin American Poetry (Seren Books, 2016), and the Cardiff-based Fiction Fiesta, and it builds on friendships with writers, and alliances with cultural organisations across Latin America. Unfinished Journey is sponsored by Wales Literature Exchange and the Club de Traductores Literarios de Buenos Aires, Argentina, with supporting partners at the Universidad Austral, in Validivia, Chile; the International Poetry Festival of Medellín, Colombia; and the Periódico de Poesía, at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México in Mexico City.’

It seems only fitting, in Octavio Paz’s Centenary year (yes, it’s not all about Dylan) that I should begin this journey in the country of, quite possibly, the 20th century’s finest ambassador for poetry. Paz, following the admirable tradition of Latin American countries in giving jobs to their poets, was also a real ambassador, to India, during which time he wrote some extraordinarily perceptive essays on Indian art and culture.

I first became interested in the literature of Mexico through the poetry of Paz and the fiction of Carlos Fuentes (I discovered years later that the two men detested each other). At a tangent, I also read the weird, apocryphal books of Carlos Castaneda with great enthusiasm, until at some point I felt he had gone off somewhere I was unable to follow. But Paz, whose Labyrinth of Solitude I encountered when I was 20, and which made a lasting impression, says this: ‘The European considers Mexico to be a country on the margin of universal history, and everything that is distant from the centre of his society strikes him as strange and impenetrable.’

I am not certain this is as true today as it was when it was written half a century ago: Europe has changed too, manifesting a slow but steady willingness to embrace minority or ‘peripheral’ perspectives (although this is not to say the work does not remain to be done, not least in the unravelling of an archaic class system based on an established white male elite). Likewise, as the Guatemalan writer Eduardo Halfon reminded me last year, the history and present of Latin America is as much based on race today as ever it was. This and other considerations, specifically those relating to Mexico, will occupy my attention, along with – I hope – more quotidian observations about the places I go and the people I meet.

So it is that today I am headed to the University in Mexico City, to meet students celebrating the festival of the book and the rose (Fiesta del libro y la rosa).

This celebration takes place on St George’s day, across the Hispanic world. I first became familiar with it during my time in Catalunya (of which St Jordi [i.e. George] is also the patron saint), a day in which lovers present each other with gifts of a book and a rose (in olden times the woman gave the man a book and the man gave the woman a rose, as women who read books were presumably not be trusted, but thankfully that part of the tradition has now been abandoned).

Later in the week, and in keeping with my brief of ‘raising the profile of Welsh culture outside of Wales’, I will be giving a lecture on Dylan Thomas in Spanish (a first for me, but given his Centenary, and given the abundance of translations of his poetry – he is, I discovered with some shock, after T.S. Eliot, the most translated 20th Century English language poet – I’m prepared to give it a punt); and I will seek to bring him into some kind of historical context, alongside R.S. Thomas and David Jones in a breakneck survey of Welsh poetry in English. Otherwise, over the next 24 days, I will be giving talks and readings of my own stuff (in the meticulous translations of Jorge Fondebrider) and travelling around the central part of Mexico, finding things to Blanquiloquise about.

‘Mexico is a country of many faces’, a teacher from Yucatán told me two and a half years ago on a previous visit to Mexico, as he drove me to the high school at Zapotlanejo where he taught history (please see Blanco’s blog about that trip in the post Dog-throwing in Zapotlanejo and other rare feats). These many faces, as in any other place, frequently appear as masks. It is something to bear in mind, as Octavio Paz reminds us in his ‘Mexican Masks’ chapter of The Labyrinth of Solitude, casting as harsh an eye on his own countrymen as R.S. Thomas ever did on the Welsh:

‘The Mexican, whether young or old, criollo or mestizo, general or labourer or lawyer, seems to me to be a person who shuts himself away to protect himself: his face is a mask and so is his smile. In his harsh solitude, which is both barbed and courteous, everything serves him as a defence: silence and words, politeness and disdain, irony and resignation. He is jealous of his own privacy and that of others, and he is afraid even to glance at his neighbour, because a mere glance can trigger the rage of these electrically charged spirits . . . his language is full of reticences, of metaphors and allusions, of unfinished phrases, while his silence is full of tints, folds, thunderheads, sudden rainbows, indecipherable threats . . . The Mexican is always remote, from the world and from other people. And also from himself.’

PS. I should note that in my last minute preparations for the Mexico leg of my ambassadorial journeyings, I read several essays from a collection of pieces on Art and Literature by Paz, in a book loaned to me, I realised with some horror, by Iwan Bala in 2001, and which, shamefully, I never returned (the non-return of loaned books stands out for me as a cardinal sin, so I am guilty of vile hypocrisy). The book is covered in Iwan’s entertaining annotations, in both Welsh and English, an added bonus, to which I have now added my own (in pencil). Iwan, if you are reading this, I will get the book back to you on my return to Wales, 13 years on, but hey, better late than never.

Reflections on a first visit to Delhi

I like vultures. No, let me start again: I think they are vile creatures, but they are a useful reminder of our mortality, and of what might happen if we are careless enough to die in a public space at which these birds are attendant. During my brief stay in Delhi last week I had the opportunity to do very little apart from attend the First Sabad World Poetry Festival, where I was surprised (as a very minor poet) to be representing the United Kingdom – as opposed to my usual country of affiliation, Wales – alongside George Szirtes, a poet I have long admired. But, to return to my point, on the one opportunity that we were allowed out on a coach trip organised by our hosts (Sahitya Akademi, an offshoot of the Indian Ministry of Culture), I took five or six photos on my iphone in the fading light, and in two of these I inadvertently snapped vultures in flight (see below). Was this foreshadowing?

For an account of the festival itself, I can do no better than refer readers to George Szirtes’ website, where he gives a pretty full (and generous) account of what went down, especially in his analysis of the differences between the performance-oriented oral traditions of poetry and the page-oriented, European style of a one-to-one encounter between poet and reader:

“The oral tradition is rooted in the following: the community, the concept of the many and the sharing of an essentially conservative, traditional and ritualist space. The voice is public. It is heard by any within earshot. It moves into the individual’s space and occupies it, asserting its confidence in shared communal values. It can talk of private matters . . . but it does so on hallowed public ground. There is an implication of physical proximity, a swaying or flowing. The collective is greater than the individual. The poet performs a priestly role, mediating between the mass and the transcendent.

The page tradition depends on the one-to-one contract between writer and reader. The book is, most of the time, read silently and reorientated as voice in the reader’s imagination. The loud and the public are suspected of being rhetorical intrusions, acts of demagoguery, The poem is a meditated space that creates an internalised physicality that may produce a faster heart-rate, tears, finger tapping and so on but within the confines of individual sensibility. It values the individual more highly than the collective. It is to some degree, or so I suspect, an extension of the protestant sense of God as someone addressed directly without mediation. Inevitably I think of Rembrandt’s self-portraits or of the monasticism of Mondrian’s abstractions.”

I recommend anyone interested to read the whole account, and indeed to subscribe to George’s blog, which he does not call a blog, but ‘News’.

Other than attend many poetry readings, some of them good, others exceptionally dull, other still (my own session, in fact) infused with the kind of spontaneously robust anarchism at which India excels, I took notes, and I ‘networked’, but I saw very little of Delhi. There was not time. My one free day, I managed to spend shopping and chasing up an exchange dealer on the black market. I did however make several observations. I realise that none of these will be of much interest to practised India wallahs, and may even appear naive or disingenuous, but they are first impressions. The first was that I am unaccustomed to, and dislike, the sense of obligatory self-abasement or servitude imposed on the vast majority of Indians, which results in you, the European visitor, being treated with ridiculous and unearned deference. A second was that I had mistakenly expected the understanding and speaking of English to be of a higher level, especially in the service industries. But I realised after a short while that proficiency in English is pretty much limited to the professional middle classes. Taxi drivers and waiters by no means routinely speak or even understand English, as the following sample illustrates:

Blanco: Can I have a large beer please?

Waiter: Yes sir. Is that being small or big?

The third thing was vultures, which I have mentioned, and a fourth was the hell that is shopping. I will never again enter a shop in Delhi to buy anything more complicated than a packet of fags. Stress levels unacceptably high. Several people at once attempt to sell you goods you do not want, and at quite exorbitant prices, unless one is prepared to haggle, which after a couple of sleepless night, I was not. Fifth, and finally, I have always tried to avoid poverty tourism, for which reason I never went to India when most my friends did, back in the 1970s. As the Sex Pistols noted, there has always seemed to be something immoral about holidays in the sun – even under the convenient guise of the gap-year experience – when the great majority of a country’s residents live in a state of abject poverty. I know there are more ethical approaches to travel nowadays, and I attempt to follow them as best I can, but India, I fear, with its lasting resonances of Empire, will always be a difficult place for a British visitor.

On a more positive note, I mentioned in my last post the musicians from Rajasthan, who played for us last Sunday evening. I was transported by their music into a zone of almost perfect bliss. It would have been worth the airfare just to listen to them, never mind the poets. Unfortunately the sound quality of my video does not do justice to the music, so I am just posting a couple of pictures instead.

Necrophiliacs of the written word

So what is poetry anyway? A rather perplexing question put about more than strictly necessary at the Sabad World Poetry Festival, which I have been attending in Delhi. On the first day, after a long haul from the airport through the dense traffic, noise, onslaught of colour and intense odour that is India, I arrived at the festival site, hosted by Sahitya Akademi and the Indian Ministry of Culture, and sat in the festival hall listening to a man sing. After he had sung his poem, or his song, they gave him a lovely bunch of yellow flowers. In fact, as I discovered, they give everyone a nice bunch of flowers (mine, on Sunday, were peach roses, which almost went with my shirt). Everyone was in a jolly good mood, what with the abundance of flowers and all. There were poets from all over the world, and especially from the subcontinent. I met up with George Szirtes from the UK, and Moya Cannon and Lorna Shaughnessy from Ireland, both of whom I have met before, and various other poets I have encountered over the past few years at festivals of this kind, including Sudeep Sen and (for the first time) the fine Indian poet Ranjit Hoskoté. There is a dancer on the second night and a sublime group of musicians from Rajasthan on the third. But I am perplexed throughout by the recurring question of ‘what is poetry?’ I mean, who really cares? One rather cool suggestion in the opening speeches (which I missed, en route from the airport) was “witnessing, wandering and wonder”. Another, which I prefer, offered to me by Moya Cannon, in a slightly different context (but which still rings true) was the opportunity to indulge our negative capability. Someone raised the point that a recent article in the Washington Post – which cites a poet who shares Blanco’s name – had pronounced poetry dead, for once and for all. Bravo, I say. That makes us so-called poets the ghouls of literature. Don’t you love that idea? Or am I merely misquoting Don DeLillo, writing of the novel, another allegedly ‘dead’ form? Either way, poet or novelist, we are obviously the necrophiliacs of the written word.

Hanif Kureishi and the ongoing but tedious debate on Creative Writing courses

“It’s a real nightmare trying to make a living as a writer”. Er . . right, mate. I’ll take your word for it (but not your course).

As someone who makes his living from the teaching of creative writing I watched warily as the Hanif Kureishi story from the Bath Literature Festival unfolded last week. I had really begun to think that the argument about ‘whether you can teach creative writing’ was dead in the ground, but I was wrong. And the tremors that began in the staid and elegant streets of Bath have even rippled over the South Atlantic.

This morning I receive an email from Jorge Fondebrider in Argentina with a link to Ñ, the magazine supplement to the newspaper Clarín, and the most important cultural weekly in the country. The article suggests that ‘Kureishi’s bitter declarations belong to the hateful species of writers who go to literary festivals in order to spend their time complaining about how much they hate having to do publicity for their books.’ Indeed, perhaps Hanif was bored, and wanted to get something off his chest, or just rile someone. And that’s understandable, although not very professional. But he certainly knew that his outburst would get him publicity for his new novel, The Last Word. I don’t wish to add to that publicity, but do feel the need to make a contribution, as I am getting tired of the argument he has resurrected. Kureishi has frequently been outspoken in a heavy-handed, bombastic way and he is a didactic writer – which to my mind is at odds with being a good novelist. But he has also –and this might come as a surprise to many – written extremely lucidly on the practice of creative writing.

What shocked most people about Kureishi’s rant was the sheer, brazen hypocrisy of it all. Here is someone who makes his living from an activity that he evidently despises – much as he appears to despise the students he teaches – and yet is content to pocket the salary that accompanies this fruitless endeavour, without any consideration for either the people who have paid big fees to study at the university where he teaches (Kingston) or the consequences for the rest of us in having to pick up the broken crockery after this moribund and incredibly tedious domestic turbulence, once again. I am not even convinced how much of Kureishi’s polemic was for real, nor do I really care. The fact is that we have all had thoughts like Kureishi’s on a bad day, but we get over it. The evidence, as Tim Clare’s entertaining response to Kureishi: Can Creative Writing Be Taught? Not If Your Teacher’s A Prick – is that many people get quite a lot from a Creative Writing course. From my own experience (I teach at Cardiff University) I would venture that MA students are not so naïve as to expect to make it into the upper zones of the literary stratosphere simply by gaining a qualification in Creative Writing. Most of them would accept that we, their tutors, cannot ‘teach them to write’, but that we can make them aware of certain techniques and strategies by which they can help themselves towards becoming better writers. Most of them would also accept that real talent – whatever that is – is rare (though whether the figure of 99.9% figure cited by Kureishi is relevant or not, I rather doubt: it reeks of the old prejudice about ‘genius’ and a ‘God-given gift’, or the equally defunct and baffling notion of inspiration from the muse). Those who do succeed (whatever the measure of success), and who possess a modicum of talent, begin with a strong urge to write – which often takes on the characteristics of an obsession – and they persevere through rewriting and rewriting until they get a result. Much as I suspect Kureishi did.

One of the modules on the Cardiff MA, taught by a colleague (Shelagh Weeks), is ‘The Teaching of Creative Writing’ (Module SET203). The assessment comes in the form of a 3,000 word essay, submitted after the students have spent some weeks working with aspiring writers in schools and with our own undergraduates. Here is a sample quotation:

‘Some students have considerable phantasies about becoming a writer, of what they think being a writer will do for them. This quickens their desire, and helps them get started. But when the student begins to get an idea of how difficult it is to complete a considerable piece of work – to write fifteen thousand good words, while becoming aware of the more or less impossibility of making significant money from writing – she will experience a dip, or ‘crash’ and become discouraged and feel helpless. The loss of a phantasy can be painful, but if the student can get through it – if the teacher can show the student that there’s something good in her work and help her endure the frustration of learning to do something difficult – the student will make better progress.’

In marking this, I would have pointed out the clumsy repetition of ‘considerable’. Nor do I much care for ‘the more or less impossibility’, but the argument being made seems sound enough.

In fact, the piece was written by Hanif Kureishi and published in issue 37 of The Reader (Spring 2010). Much more helpful than the Kureishi who tells us that creative writing courses are simply a waste of time.

An inexplicable addiction

A joy to find this passage in the Freelance slot of last week’s TLS, written by the wonderful Lydia Davis:

“In spite of having translated during most of my life, I still don’t really understand the urge. Why can’t I simply enjoy reading the story in its own language. Or, on the other hand, why can’t I be content to write my own work in English? The urge is a kind of hunger; maybe the polite word would be appetite – I want to consume the text, and reproduce it in English . . . Or is translation merely a less demanding or anguishing mode of writing? The piece exists already in the other language, beautifully conceived and formed; now I will have the pleasure of composing it in English, without the uncertainty involved in inventing it. Or is it acquisitiveness? I want to take over something that does not belong to me, and by writing it in English, claim it. I don’t have a completely satisfactory answer. The desire to translate may be something of an inexplicable addiction.”

Three things I learned from Cavafy

For a long time, while I was tramping around southern Europe, escaping the collective embarrassment that was Britain in the 1980s, I carried with me the poems of CP Cavafy. Other books I picked up and discarded along the way, but Cavafy, in one edition or another, stayed with me for much of the decade. I forget the precise circumstances that led to me making this choice, but most likely it was not a choice at all; I suspect the book was dropped into my bag by a passing sprite, concerned for the welfare of an ephebe like myself, setting out into solitary exile to learn, among other things, the road of excess and the skills of guile and trickery. It would suit my story if this were the case, but the truth is I had been reading Cavafy since I was sixteen, and once he had become a staple of my travels, I didn’t feel properly equipped without him. A slim volume, joined during those early years by Borges’ Fictions and Calvino’s Invisible Cities. These three books had three things in common: they were all small-scale and dense; they all subverted familiar stylistic mannerisms; and they were all conceived in the element of mercury. One thing I didn’t know then was that forty years later I would still be reading Cavafy, with more curiosity than ever.

If we are lucky, we get the writers we deserve, and at the right time of life. Reading Cavafy at a young age nurtured in me the then enthralling (but now merely fashionable) notion that time is not a linear construct, but rather resembles a shifting, mutable state in which past and present might be accessed simultaneously. Cavafy’s poetry, as Patrick Leigh Fermor once wrote, skilfully interweaves time and myth and reality, allowing for a particular kind of mutability, an ability to flit between perceptive modes that, once grasped, will stay with the reader always. If that sounds grandiose, I would like to clarify: there is no distinction in these poems – I would like to say in life, also – between what is imagined and the literal or mechanistic world of everyday understanding, and we must appreciate that this is essential to a proper appraisal of Cavafy. There is no point in conceding to the sordid demand for what ‘really happened’, claiming that any other version is a fantasy or a dream, and that reality is ‘out there’, the other side of the window, any more than one can discern, in Cavafy’s work, between the literal Alexandria and the one held in his imagination. In Cavafy’s poetic world the two are one and they merge, diverge and re-converge continually.

When I was eighteen I spent a summer living in an abandoned shepherd’s hut on a hillside overlooking the Libyan sea in southern Crete, near the tiny village of Keratokambos. Reading outside one evening, I heard an exchange of voices. In the near distance, some way above me, a man and a woman were calling to each other, each voice lifting with a strange and powerful vibrancy across the gorge that lay between one flank of the mountain and the next. Only the nearer figure, the man, was visible, and his voice seemed to rebound off the wall of a chasm, half a mile away. The woman remained out of sight, but her voice likewise drifted across the gorge, with crystalline clarity. There were perhaps a dozen exchanges: and then silence. I listened, spellbound. And that brief exchange, that shouted conversation, with its strange sounds, the tension between the voices, the exhalations and long vowels echoing off the sides of the mountain, would haunt me for years, haunts me still. They seemed to me to be speaking across time, that man and woman. Their ancestors, or possibly they themselves, had been having that conversation, exchanging those same sounds, for millennia. It was, for me, a lesson in the durability of human culture and at the same time, the incredible fragility of our lives; the conversation, the calling across the chasm, represented our ultimately solitary and unique chance at communication with a presence beyond ourselves. It was the vocal correlative of a strange sensation that I had experienced since first arriving in Crete: everywhere I went I was walking on bones, walking on the bones of the dead; and now I was hearing the echo of their voices as well.

In ‘Ionic’, translated more recently by Daniel Mendelsohn as ‘Song of Ionia’, Cavafy sums up an exemplary moment, suggesting that despite the destruction of their monuments and statues, the old gods still dart among the hills on the coast of Ionia (today’s western Anatolia), and it concludes with the lines:

When an August morning dawns over you,

your atmosphere is potent with their life,

and sometimes a young ethereal figure

indistinct, in rapid flight,

wings across your hills.

Here, the ‘young ethereal figure’ is surely Hermes. He is, after all, the winged god, and the god of transition and boundaries, and therefore more than likely to be seen at dawn, in the breach between night and day. Perhaps the Hermes association is personal, owing to the fact that in my experience, Hermes, god of travellers, was almost always the one who came to sort out the mess after Dionysos had wreaked his havoc. It seems likely, according to Daniel Mendelsohn’s wonderfully thorough notes that Cavafy, too, was thinking of Hermes, although I did not know this when I first read the poem.

That the past cohabits eternally with the present is a specifically Cavafian notion, and this subversion of linear time was the first thing I learned from his poetry. The second was his unique conceptualisation of place, in relation to the city with which his name has become ineluctably associated, Alexandria. As Edmund Keeley points out, Cavafy was the first of his contemporaries (woh included Yeats, Pound, Joyce and Eliot in the English-speaking world) to ‘project a coherent poetic image of the mythical city that shaped his vision’. His poetic vision – even when concerned with matters of erotic desire, which it often is – involves a constant pursuit of ‘the hidden metaphoric possibilities, the mysterious invisible processions, of the reality one sees in the literal city outside one’s window’. Cavafy takes the idea of the city and expands upon it so that it carries mythic significance. The poem he chose to begin his first pamphlet of work, distributed among friends, is, significantly, ‘The City’. The poem is addressed to one whose life is bound by literal time and literal thought while, by contrast, the poet-narrator lives according to other parameters, which are timeless. Like other great poets Cavafy mythologises a personal landscape so that it becomes universal:

You won’t find a new country, won’t find another shore.

This city will always pursue you.

You’ll walk the same streets, grow old

in the same neighbourhoods, turn grey in these same houses.

You’ll always end up in this city. Don’t hope for things elsewhere:

there’s no ship for you, there’s no road.

Now that you’ve wasted your life here, in this small corner,

you’ve destroyed it everywhere else in the world.

The poet’s difficulties over the composition of ‘The City’ – fifteen years lapsing between the first draft in 1894 and publication – are perhaps a reflection of Cavafy’s uncertainty over whether or not he wanted to settle permanently in Alexandria, or himself ‘find some other city’, like the protagonist of his poem. ‘What trouble, what a burden small cities are’, the forty-four year-old poet complained in an unpublished note, dated 1907. He apparently made up his mind to stay by 1910, the year that ‘The City’ was published. It would seem that around this time he experienced an epiphany or at least a shift in his trajectory as a writer, deciding that his destiny lay with Alexandria, and that he would probably never leave. The choice of ‘The City’ as the lead poem in published selections of his work is as intentional as, say, Wallace Stevens’ insistence on ‘Earthy Anecdote’ opening all collected editions of his poetry. Alexandria became, from that point on, the principle vehicle for his poetic imagination. Conscious of this, he again addresses the theme of leaving the city – actually of being abandoned by the personified city – in ‘The God Abandons Anthony’, when the speaker admonishes the Roman general, who was closely associated with the god Dionysos, at the moment of departure:

When suddenly, at midnight, you hear

an invisible procession going by

with exquisite music, voices,

don’t mourn your luck that’s failing now,

work gone wrong, your plans

all proving deceptive – don’t mourn them uselessly:

as one long prepared, and full of courage,

say goodbye to her, to Alexandria who is leaving.

Above all, don’t fool yourself, don’t say

it was a dream, your ears deceived you:

don’t degrade yourself with empty hopes like these . . .

It is this self-degradation with false hopes, this yearning for the sacred centre, the object of desire that can never be attained, the love that will never be requited, which makes of all of us an Anthony. Whenever one thinks one has arrived at one’s destination, then will be the time to move on. There is no way of making peace with any objective, real or imagined, until one has first made peace with oneself, and the process is self-perpetuating, and the cities mount up. ‘The more you travel’ as the Turkish poet Adnan Özer writes, ‘the more cities you will find within yourself’.

So, the second thing I learned from Cavafy was that the city is a cypher for the self, reflecting our fragmented or multiple selves. We know that Cavafy is speaking of Alexandria, but we also know that the city is a state of mind – one’s personal predicament, and the human predicament also – from which we can never be free.

The third thing I learned from Cavafy is that we are always at risk of misreading the signs and portents that surround us: arrogance and self-satisfaction dim our vision and make us ridiculous. It is a favourite theme of Cavafy’s, most often delivered with a profound sense of irony. Let us consider the poem ‘Nero’s deadline’:

Nero wasn’t worried at all when he heard

what the Delphic Oracle had to say:

“Beware the age of seventy-three.”

Plenty of time to enjoy himself.

He’s thirty. The deadline

the god has given him is quite enough

to cope with future dangers.

Now, a little tired, he’ll return to Rome –

but wonderfully tired from that journey

devoted entirely to pleasure:

theatres, garden-parties, stadiums . . .

evenings in the cities of Achaia . . .

and, above all, the delight of naked bodies . . .

So much for Nero. And in Spain Galba

secretly musters and drills his army –

Galba, now in his seventy-third year.

At a superficial reading, the conceited, megalomaniac Nero, cosseted by the apparently safe verdict of the oracle, is undone by his comprehensive misunderstanding of its hidden message. But as Mendelssohn points out, the poem does more than make fun of Nero’s self-satisfied complacency, it puts forward Galba as the avenging hero, come from obscurity in his old age to save Rome. However, Galba, in turn, was a disaster for Rome, his greed and lack of judgement causing him to be murdered seven months after his accession as Emperor, on the orders of Marcus Salvius Otho, a fellow-conspirator against Nero. (Otho, incidentally, lasted only three months as Emperor before stabbing himself in the heart). ‘Nero’s deadline’ offers a cinematic vignette of power’s corrupting influence. And by omitting Galba’s own downfall – assuming, as he so often does, that the interested reader, if curious enough, will find out – Cavafy adds a layer of hidden significance to a piece that already works as a denunciation of grandiosity and hubris. The poem reveals betrayal lying beneath betrayal, all of it stemming from overreaching and a smug belief in one’s own achievements, only for each incumbent to meet with a grisly end.

I wanted to write this essay in order to find out why Cavafy has held such a longstanding fascination for me as a reader (and therefore as a writer, since the two activities are composite: we read, at least in part, in order to learn, or to steal). I have discussed three things that are particularly important in my own understanding of his work. But there is something else, greater than the sum of its parts, which asserts this man’s comprehensive poetic vision. Cavafy was a poet who, throughout his life, was – in Seferis’ words – “constantly discovering things that are new and very valuable”. It may be that this capacity for discovery, a reflexivity regarding his personal as well as a collective Hellenic past, his subtly revelatory intelligence, are somehow transmitted onward, and we, as readers, are infected by his own enthusiasms. “He left us with the bitter curiosity that we feel about a man who has been lost to us in the prime of life,” wrote Seferis. This is not simply on account of his relatively small output, but because of its seeming unity of construction and purpose, its sense of unfulfilled possibility, and the poet’s curiosity at being in a world in which past and present merge in an invisible procession.

Translations from the Greek are by Edmund Keeley & Philip Sherrard in C.P. Cavafy: Collected Poems, Chatto & Windus, 1990. The references to Daniel Mendelssohn concern the notes to his own translations in C.P. Cavafy: Complete Poems, Harper Press, 2013.

First published as ‘An Invisible Procession: How reading Cavafy changed my life’, in Poetry Review, 103:3 Autumn 2013.

Facts about Things

Omnesia, W.N. Herbert’s new collection of poetry, comes in two volumes, subversively titled Alternative Text and Remix, so as to disabuse the reader of any notion of an ‘original’. The word ‘omnesia’ is a conflation of omniscience and amnesia, the latter quality bringing into question the actuality of everything we know – especially, perhaps, our omniscience.

Omnesia, W.N. Herbert’s new collection of poetry, comes in two volumes, subversively titled Alternative Text and Remix, so as to disabuse the reader of any notion of an ‘original’. The word ‘omnesia’ is a conflation of omniscience and amnesia, the latter quality bringing into question the actuality of everything we know – especially, perhaps, our omniscience.

Herbert’s oeuvre is already varied and profuse, and this new collection is expansive in every way. The two volumes mirror and reflect upon each other, so that the airborne squid on the cover of ‘Alternative Text’ is flying towards the reader while the one on ‘Remix’ travels laterally – just as the author in the photo gazes amusedly to the right on the one book, and bemusedly to the left on the other. As an epigraph from Juan Calzadilla, tells us: ‘I have transformed myself into another / and the role is going well for me’. The concept of non-identical twin texts embodies, as the poet reminds us in his Preface, a rejection of ‘or’ in favour of ‘and’. A core of poems appears in both volumes, and the title poem opens ‘Alternative Text’ and closes ‘Remix’. But this sequencing does not signify a preferred reading order. Instead, we are warned off any kind of systemic coherence in the poem’s opening lines: ‘I left my bunnet on a train / Glenmorangie upon the plane, / I dropped my notebook down a drain; /I failed to try or to explain, / I lost my gang but kept your chain – / say, shall these summers come again, / Omnesia?’

Almost anything is a cue to Herbert, setting him off on one of his preferred riffs, especially our inescapable doubleness, exemplified by the two books – themselves containing other books which scurry off at tangents – and the frequent collusion of the narrative ‘I’ with other selves. In ‘Paskha’, the narrator sees a dead scorpion ‘in silhouetted crux’ and is ‘troubled by the brain’s chimeric quoins / its both-at-onceness, how the memory’s / assembled with our present self for parts . . .’ And it is this very both-at-onceness that has me riffling through the pages of ‘Alternative Text’ while reading ‘Remix’, following the demands of a connectivity which the poet’s Preface planted at the outset.

The poems take place in and meditate upon the poet’s journeys from Crete to the north of Britain, from Mongolia to Albania, from Finland to Israel, from Venezuela to Siberia, and among the poet’s several antecedents I was pleased to meet the shadow of Byron, especially in the ‘Pilgrim’ sequence. There is also a fine selection of poems in Scots.

The choice of epigraph usually serves as a pointer towards the poet’s intended direction. We are warned, in a quotation from Patricia Storace, that ‘In Greece, when you hear a story, you must expect to hear its shadow, the simultaneous counterstory.’ And not just in Greece. In ‘News from Hargeisa’, for instance, the counterstory of Somalia’s troubled history lies beneath every line, evoking local parable in the story of a lion, a hyena and a fox (animal imagery predominates in many of Herbert’s poems), as well as in the poet’s mourning of his friend Maxamed Xaasi Dhamac, known as ‘Gaarriye’, the late great Somali poet to whom both volumes are dedicated.

I am sure I missed subtle allusions and even whole thematic directions, and yet still enjoyed the poems I didn’t get. I did wonder how many people – outside of those who have lived on Crete – would ‘get’ ‘The Palikari Scale of Cretan Driving Scales’, a poem in which the driver’s recklessness is measured in direct relation to the magnificence of his moustache.

One might complain that there is simply too much in these books: not in the sense that they are lacking in editorial discretion, but that they demand a readerly imagination as febrile as Herbert’s in order to keep up. Is W.N. Herbert one person? I suspect not: and in any case he seems quite comfortable swapping costumes with his multiple others. I suspect also that Omnesia is a work one needs to live with for a while before appreciating all the shifts and mirrorings, puns and doublings, but even on a first acquaintance it offers richly rewarding reading.

Review published in Poetry Wales, Summer 2013 49 vol 1.

And nearly a year having passed since writing the above review, I can assure you that Omnesia repays revisiting. In so many ways.

Facts about Things

Things are tired.

Things like to lie down.

Things are happiest when,

for no reason, they collapse.

That French plastic bottle, still half-full,

that soft-back book, just leaning on

another book, drowsily:

soon they will want to go outside,

soon you will find them in the grass

with the empty bleaching cans and that part

of an estate agent’s sign

that’s covered in a fine grime like mascara.

That plastic bag you’ve folded up

feels constrained by you and wants

to hang from bushes, looking like a spirit,

sprawled and thumbing a lift.

Things are bums, tramps, transitories:

they prefer it when it’s raining.

Lightbulbs like to lie in that same

long, uncut, casual grass

and watch the funnel effect: the way

on looking up the rain all seems

to bend towards you,

the way the rain seems to like you.

Things which do not decay

like it best in shrubbery, they like

to be partly buried.

They like the coolness of the grass.

Most of all, they like it

when it rains.