The people of Teotihuacán

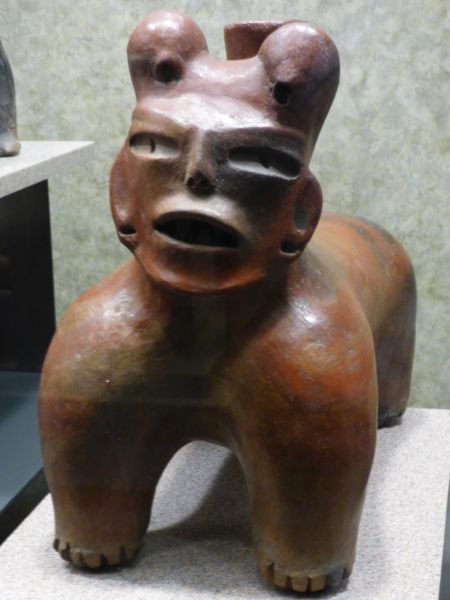

It is not known who built and occupied Teotihuacán (pronounced tay-oh-tee-wah-kahn): the Totonac, Otomi or Nahua peoples have all been put forward. The site was established before 100 B.C and building of the vast pyramids continued until around 250 A.D. The city reached its zenith over the next three centuries, with a population in excess of 125,000, making it one of the largest cities in the world at the time. It was sacked and burned in the middle of the 6th century and was abandoned by 700 A.D. The fortunes and whereabouts of the people who built and occupied this city vanish alongside numerous Mesoamerican cultures with the rise of the Azteca-Mexica people, but we know that evidence of Teotihuacano influence can be seen at sites in the Veracruz area. And it was here, in 1519, that Hernán Cortés made his first inroads towards the Aztec capital Tenochtitlan (modern day Mexcio City), a city which he effectively destroyed two years later.

The site at Teotihuacán covers a huge area, of which only about a quarter has been excavated. The principle monuments, the Temples of the Sun and Moon, and the Temple of Quetzalcóatl, are joined by the Avenue of the Dead. The configuration of these building has been subject to intense speculation, ranging from the more scientific to New Age Bonkers (while I was at the top of the Temple of the Sun a European-looking woman, dressed in flowing gowns, opened her arms to the sun and started chanting some gobbledygook which she obviously believed was connecting her to something or other). In the 1970s heyday of New Age enthusiasts, a survey was carried out by Hugh Harleston Junior, who found that the main structures lined up along the Avenue of the Dead formed a precise scale model of the solar system, including Uranus, Neptune and Pluto (not discovered until 1787, 1846 and 1930 respectively). There is plenty more of this kind of stuff around, and every Spring Equinox morning thousands of people climb the Temple of the Sun with arms outstretched facing the sun on the eastern horizon. According to the Wikipedia article on this phenomenon:

Some New Age sources claim that at the point of the equinox, man is at a unique place in the cosmos, when portals of energy open. Climbing the 360 stairs to the top of the Pyramid of the Sun is claimed to allow participants to be closer to this “energy”.

Although recent research suggests that Teotihuacán was a multi-ethnic state, we do know that the Totonac people, who may have lived there, later bore a mighty grudge against their conquerors, the Aztecs, who regularly took tribute from them of slaves, many if not all of whom would be sacrificed. But the people who lived in Teotihuacán certainly practised human sacrifice also. I don’t know how far the New Agers go along with that kind of thing, but who knows, perhaps they secretly want to be sacrificed.

As part of my background reading into Mexican history I am currently immersed in the 19th century Hispanist William F. Prescott’s fascinating account The Conquest of Mexico (published in 1843). I know there are more up-to-date and scientific studies of the period, but none are as entertaining (and Prescott’s study can be downloaded onto a Kindle for only 99 pence). It is written in a style that wavers between the deferential and the ornate, which was no doubt intended to convey the maximum sense of verisimilitude, but which to a modern reader– and possibly, who knows, to the Victorians also – seems almost to verge into parody. Here is Prescott on Cortés’ arbitrary method of convincing the Totonacs that their religious and dietary preferences (i.e. worshipping wooden idols and eating people) were wrong, and they would be much better off serving the True Cross):

‘Fifty soldiers, at a signal from [Cortés], sprang up the great stairway of the temple [at Cempoala], entered the building on the summit, the walls of which were black with human gore, tore down the huge wooden symbols from their foundations, and dragged then to the edge of the terrace. Their fantastic forms and features, conveying a symbolic meaning, which was lost on the Spaniards, seemed in their eyes only the hideous lineaments of Satan. With great alacrity they rolled the colossal monsters down the steps of the pyramid, amidst the triumphant shouts of their own companions, and the groans and lamentations of the natives. They then consummated the whole by burning them in the presence of the assembled multitude.

The Totonacs, finding their deities incapable of preventing or even punishing this profanation of their shrines, conceived a mean opinion of their power, compared with that of the mysterious and formidable strangers. The floor and walls of the teocalli were then cleansed, by command of Cortés, from their foul impurities; a fresh coating of stucco was laid on them by Indian masons; and an altar was raised, surmounted by a lofty cross, and hung with garlands of roses. A procession was next formed, in which some of the principal Totonac priests, exchanging their dark mantles for robes of white, carried lighted candles in their hands; while an image of the Virgin, half smothered under the weight of flowers, was borne aloft, and, as the procession climbed the steps of the temple, was deposited above the altar. Mass was performed by Father Olmedo, and the impressive character of the ceremony and the passionate eloquence of the good priest touched the feelings of the motley audience, until Indians as well as Spaniards, if we may trust the chronicler, were melted into tears and audible sobs.’

This sprightly conversion was guided, in part at least, by the Totonac cacique’s knowledge that only with the support of the Spaniards could he gain revenge on his real enemy, the Aztec.

Back in Teotihuacán, I complete my ascent of both the Temple of the Moon and the Temple of the Sun (exhausting and at times perilous) and make my way along the Avenue of the Dead, to the visit the Temple of Quetzalcoatl (ket-sal-kwaht-uhl) – the plumed serpent deity – which is far smaller, but equally impressive in its way. Its façade is adorned with huge sculptures of a plumed serpent and of the rain god Tlaloc. A series of tunnels were found beneath the structure in 2010. They are thought to house the remains of the ruling elite.

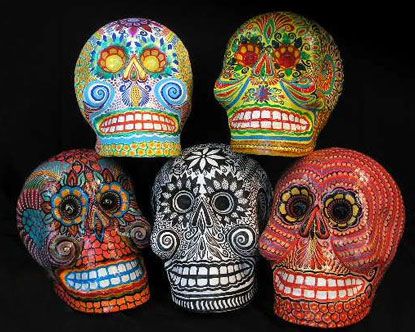

Nearby is the site of several mass graves, discovered in the 1980s. The remains of around 200 people who had been sacrificed were found, the victims’ hands tied behind their back (perhaps dispelling the notion that some Mesoamerican sacrifice victims were volunteers). Whichever version is true (and we know that sacrificial victims were most commonly captured enemies), we return again to the cult of death, which I have remarked upon in previous posts during this trip, and to which I will return.