Notes from a Catalan village: summer on its way

The weather has been cloudy, windy and wet for much of May – validating the Catalan proverb, Al maig, cada dia un raig (in May, a shower every day) – with just the occasional day of glorious sunshine, when we take off for a walk, just to reassure ourselves that summer is really coming. On one of these occasions, wandering round the lanes near the village, we came upon this goat, standing in proprietorial fashion in the doorway of a caravan. She stared at us as we passed, not remotely deterred by the dog, who wisely stayed away.

Spring started a long time ago now, announced by the cherry blossom in February. It always seems to me that the summer is on its way when the first shoots appear on the vines, in early April. The poppies shoot up at the same time, bestowing on the olive groves a scattering of scarlet.

The first tourists start to appear then too, almost exclusively French at this time of year, driving in the middle of the road on country lanes, and getting lost in the medieval labyrinth of the village.

One of the walks we took a couple of weeks back was to the Santuari de la Mare de Deu, near Terrades. A half hour’s climb to a tiny chapel rewards with views of Canigou and beyond.

Chapel on mountain at Santuari de la Mare de Deu, near Terrades

Another of my favourite places, all year round, which still provides unspoiled beaches out of season, is Cap Norfeu – named after Orpheus – on the Cap de Creus peninsula, where, if you listen carefully, you can hear strains of song from below the cliffs. But don’t venture too close. Or go stepping on any snakes. You might end up in the underworld.

Cala Pelosa and Cala Montjoi from Cap Norfeu

I kill out of rage

An exhibit by the artist Alfredo Lopez Casanova, using the shoes of missing people with messages on their soles, in an exhibition currently running at the ‘Casa de la Memoria Indomita’ in Mexico City, titled ‘Huellas de la Memoria‘ (Memory Traces).

Since posting María Rivera’s ‘The Dead’ on Wednesday, over 500 people have checked in, and María herself emailed to thank me for posting her poem. ‘The Dead’ evoked some powerful responses from readers. Echoing the views of others, John Freeman commented (on FB) that María achieves something he thought was ‘impossible to do – for a poet to create such emotional immediacy with such a sweep of large political anger’.

Shortly after encountering María’s poem, my friend Carlos López Beltrán directed me towards another fine poem – again by a woman – that addresses the terrible swathe of violence in which Mexico has been immersed for the past decade. It appears in the anthology of Mexican Poetry edited by Pedro Serrano and Carlos himself, and titled 359 Delicados (con filtro), (Santiago de Chile: Lom, 2012).

The poem, ‘I kill out of rage’, by Claudia Hernández de Valle-Arizpe, adopts the voice of an assassin, reciting a list of random, barbaric ‘reasons’ for random, barbaric murder. In the poem the act of killing builds up its own terrible momentum, so that in the second stanza, the possibilities – or potential – for murder extend even to those hypothetical victims who are not killed on this occasion, but who might just as easily have been, according to the appalling logic that propels the actions of the poem’s speaker.

This poem, along with 156 others by 97 Latin American poets, selected and translated by Richard Gwyn, will be published in October 2016 in The Other Tiger: Recent Poetry from Latin America, from Seren Books.

‘Mato por rabia’ first appeared in the collection Perros muy azules, México DF: Era (2012).

I Kill out of Rage

by Claudia Hernández de Valle-Arizpe (México)

I kill out of rage, out of hatred, out of spite; I kill from jealousy,

for revenge; I kill to bring justice (for me or for you),

so that you understand for once and for all, to get a rest

from you; I kill out of fear, to rob, to flee, to defend myself;

I kill out of habit, for fun; I kill as a reaction;

so that you don’t kill me, so that you don’t rape me. I kill because

I can’t bear it anymore, because I want to die but don’t dare,

because even children kill, because I’m sick because

I’m crazy, because I’m sad, because nobody loves me anymore.

I kill in the name of my religion, in the name of my people,

of freedom, of democracy. I kill in the name of God.

And also I kill because here I feel like it, in the shack,

in the neighbourhood, in the nightclub, on the road, in your house, in mine.

I kill for drugs, because it excites me, because it’s exercise, because

one day it’s me they’re going to kill. I kill dogs, cats, pigs, people.

I kill who’s going past in the street, or sleeping, or having fun.

I kill with weapons so that there’s blood, so that the blood runs

like my rage, my weariness, my injustice, my ugliness, my sex,

my obesity, my diabetes, my cirrhosis, my cancer, my mental retardation,

my stupidity, my nightmares, my hopeless life.

I kill you but could kill your sister, your father, your wife,

your children, your lover, your grandmother, your dog. I kill you today but

don’t trust me, because I can kill you tomorrow, any day,

with bullets that will pierce your lung and your stomach

and will lodge, very hot, in your neck, in your groin,

in your head. And what is yours will be no one’s, you see: what you proclaimed,

what you did, what you knew, what you liked so much: your mornings,

your nights in company, your memories, your plans, all of this will bite

the dust. Bullets, brother, bullets; what a tragedy, what sorrow,

those who knew you will cry, and you now in ashes, man,

woman, child, ugly, pretty, ignorant, brilliant, poor, rich, whatever.

Have you ever killed? Have you tried to?

Shoot, says the killer to the boy,

or don’t you dare?

There has never been a weapon in my house, there never was,

I have never fired a shot.

Mato por rabia

Mato por rabia, por odio, por despecho; mato por celos,

por venganza; mato para hacer(me), hacer(te) justicia.

Para que entiendas de una vez y para siempre, para descansar

de ti; mato por miedo, para robar, para huir, para defenderme;

mato por hábito, para divertirme; mato por reacción,

para que no me mates, para que no me violes. Mato porque

ya no aguanto, porque quiero morirme pero no me atrevo,

porque hasta los niños matan, porque estoy enfermo, porque

estoy loco, porque estoy triste, porque ya nadie me quiere.

Mato en nombre de mi religión, en nombre de mi pueblo,

de la libertad, de la democracia. Mato en nombre de Dios.

Y también mato porque se me da la gana aquí, en la chabola,

en el barrio, en el antro, en la carretera, en tu casa, en la mía.

Mato por droga, porque me excita, porque me ejercito, porque

un día a mí me van a matar. Mato perros, gatos, puercos, gente.

Mato al que va en la calle, al que duerme, al que se divierte.

Mato con armas para que haya sangre, para que corra la sangre

como mi rabia, mi hartazgo, mi injusticia, mi fealdad, mi sexo,

mi gordura, mi diabetes, mi cirrosis, mi cáncer, mi retraso mental,

mi estupidez, mis pesadillas, mi vida sin remedio.

Te mato a ti pero puedo matar a tu hermana, a tu padre, a tu mujer,

a tus hijos, a tu amante, a tu abuela, a tu perro. Te mato hoy pero

no confíes porque puedo matarte mañana, cualquier día,

con las balas que van a perforar tu pulmón y tu estomago

y que se alojarán, muy calientes, en tu cuello, en tus ingles,

en tu cabeza. Y lo tuyo no será de nadie, ya ves, lo que pregonaste,

lo que hiciste, lo que sabías, lo que tanto te gustaba: tus mañanas,

tus noches acompañado, tus recuerdos, tus planes, todo se lo comerá

el acero. Bullets, hermano, bullets; qué tragedia, que dolor,

van a gritar los que te conocieron, y tú ya en cenizas, hombre,

mujer, niño, feo, bonito, bruto, genial, pobre, rico, qué importa.

¿Mataste alguna vez? ¿Lo has intentado?

Dispara, le dice el asesino al muchacho,

¿o es que no te atreves?

Nunca ha habido un arma en mi casa, nunca la hubo,

nunca he disparado.

Facing Rabbit Island

Facing Rabbit Island

That night we came down

from the colony on the hillside.

The afternoon had strewn

about our heads

a debris of hyperbole

and vague menace.

Bewildered before

the declaiming of Hikmet

by an Air Force General,

cast into stupor

by amphitheatre kitsch,

we sought out the solace

of the purple seaboard,

along with something darker.

But our path was convoluted

– the geography, as someone once

remarked, would not stay still –

and the road abandoned us.

A big white dog appeared, on cue,

led us to the village of Gümüslük.

Across a narrow stretch of sea

lay Rabbit Island.

I might have swum the strait,

but feared the straying tentacles

of confused sea creatures.

Everywhere was closed,

and what wasn’t closed

was closing in. Fishing boats

rocked gently in the harbour;

the awnings of the restaurants

pulled down, dark and silent.

No movement in the street

besides those watchful cats.

I looked to our canine guide,

but he had slipped away.

No respite from the labyrinth,

it pursues you

even when you think

you have evaded it,

sucks you in deeper,

lets you wander, trancelike,

from one variety of despair

to another, presents you

with a chthonic version of yourself,

the one that leads you back

at five a.m. to stagnant water,

the merciless mocking of the frogs,

the ironic moon.

Ballad of the House

Colombian poet Romulo Bustos Aguirre

Last Tuesday saw the launch in Bogotá of Rómulo Bustos Aguirre’s Collected Poems (1988-2013), La pupila incesante. The event was introduced by another fine Colombian poet, Darío Jaramillo Agudelo. Both poets feature in my forthcoming anthology, The Other Tiger: Recent Poetry from Latin America, to be published by Seren in October. Using a language rich in metaphysical allusion and sensual imagery, Rómulo Bustos is a writer of ‘slow’ poetry, inspired by the landscape and themes of his native Caribbean. A professor of literature at the University of Cartagena, he has won the National Poetry Prize from the Instituto Colombiano de Cultura, and the Blas de Otero Prize from the Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Here is my translation of a poem of Rómulo’s, which was published in the Irish poetry magazine Cyphers, back in December 2014.

Ballad of the House

You will find a house with a strange name that you will attempt in vain to decipher And walls the colour of good dreams But you will not see that colour Nor will you drink the red plum wine that expands memories On the fence a child with a half-open book Ask him the way to the big trees whose fruits are guarded by an animal that sends passers-by to sleep just by looking at them And he will answer while conversing with a green-winged angel (as if it were another child playing at being an angel with wide banana leaves stuck to his back) barely moving his lips in a gentle spell “the cockerel’s song isn’t blue but a sleepy pink like the first light of day” And you will not understand. And nevertheless you will find an immense hallway that I crossed where the portrait of a lord hangs, shimmering slightly, his heart in his hand And at the back, right at the back, the soul of the house seated in a rocking chair, singing But you will not heed her Because in that instant A distant sound shall crumple the horizon And the child will have finished the last page

Translation by Richard Gwyn

Balada de la casa

Hallarás una casa con un nombre extraño

que intentarás descifrar en vano

Y muros del color de los buenos sueños

Pero tú no verás ese color

Tampoco beberás el vino rojo de los ciruelos

que ensancha los recuerdos

En la verja

un niño con un libro entreabierto

Pregúntale por el camino de los grandes árboles

cuyos frutos guarda un animal

que adormece a los andantes con sólo mirarlos

Y él contestará mientras conversa

con un ángel de alas verdes

(como si fuera otro niño que juega al ángel

y se hubiera colocado anchas hojas de plátano a la espalda)

moviendo apenas los labios en un leve conjuro

“el canto del gallo no es azul sino de un rosa dormido

como el primer claro del día”

Y tú no entenderás. Y sin embargo

hallarás un zaguán que yo recorrí inmenso

donde cuelga el retrato de un señor que resplandece

levemente, con el corazón en la mano

Y al fondo, muy al fondo

el alma de la casa sentada en una mecedora, cantando

Pero tú no la escucharás

Pues, en ese instante

Un sonido lejano ajará el horizonte

Y el niño habrá pasado la última de las páginas

Rómulo Bustos Aguirre (Colombia)

The War of the Idiots

The War of the Idiots

by Beatriz Vignoli (Argentina)

We dynamited the bridge before ever

crossing it, the lovely bridge

that we built.

The bridge over the river of forgetfulness, it was.

Now we will die forgotten.

Let’s die then, and from this.

Translation by Richard Gwyn.

La Guerra de los tontos

Dinamitamos antes de cruzarlo

el puente, el bello puente

que habíamos construido.

El puente sobre el río del olvido era.

Ahora, moriremos olvidados.

Muramos ya, y de esto.

‘La Guerra de los tontos’ was first published in Beatriz Vignoli’s collection Viernes, Bajolaluna, Buenos Aires, 2001.

This poem, along with 155 others by 97 Latin American poets, will be published in October 2016, in the anthology The Other Tiger: Recent Poetry from Latin America, from Seren Books.

Creative Nonfiction

Geoff Dyer, Brixton, London, 1988

I find a great Paris Review interview in ‘The Art of Nonfiction’ series from a couple of years ago with Geoff Dyer, who begins by disagreeing with the parameters of his own interview, interrupting the interviewer as follows:

INTERVIEWER

The first thing I’d like—

DYER

Excuse me for interrupting, but—at the risk of sounding like some war criminal in the Hague who refuses to acknowledge the legitimacy of the court in which he’s being tried—I have to object to the parameters of this interview.

INTERVIEWER

On what grounds?

DYER

It’s titled “The Art of Nonfiction.” Now I could whine, “What about the fiction?” but that would be to accept a distinction that’s not sustainable. Fiction, nonfiction—the two are bleeding into each other all the time.

INTERVIEWER

You don’t distinguish between them at all?

DYER

I don’t think a reasonable assessment of what I’ve been up to in the last however many years is possible if one accepts segregation. That refusal is part of what the books are about. I think of all of them as, um, what’s the word? Ah, yes, books. I haven’t subjected it to scientific analysis, but if you look at the proportion of made-up stuff in the so-called novels versus the proportion of made-up stuff in the others, I would expect they’re pretty much the same.

Later in the interview, Dyer makes mention of David Hare’s remark that the two most depressing words in the English language are ‘literary fiction’, and then goes on to add that ‘creative nonfiction’ might well have taken over as the most odious of collocations. Since I teach a module entitled precisely ‘creative nonfiction’ at the university where I work, I am going to have to think out a pretty clear disclaimer at the start of each semester. Well, the kind of disclaimer I make already, to be fair.

Essentially we are talking about a distinction with which readers of this blog will be familiar, if not, I hope, entirely bored. ‘Creative nonfiction’ is creative by virtue (I guess) of having been written, and ‘nonfiction’, I suppose, by virtue of it not being ’fiction’, or ‘made up’. (I note also that the term itself used to be hyphenated (non-fiction), making it a challenge to, or questioning of, the thing it was not, but now that the hyphen has gone, the beast has been assimilated as a single concept, wearing its non-ness with pride, as it were). So Nonfiction is defined by what it is not. It is not ‘made up stuff’, but stuff that really happened. However, following the criteria established by Borges, and discussed by Blanco here, that ‘everything is fiction’ then how can such a genre as ‘nonfiction’, let alone ‘creative nonfiction’ occur? Why do we need these ridiculous denominations? Why can we not, as Dyer suggests, just have ‘books’?

In his account of acting as W.G. Sebald’s publisher, Christopher MacLehose describes Sebald’s resistance to The Rings of Saturn as being categorised within any literary genre at all: memoir, history, fiction, holocaust studies, travel writing etc: he wanted ‘all of them’, claims MacLehose – and yet, one suspects, at the same time, he wanted none of them. MacLehose says that the craving for categorisation makes booksellers happy, so that they can put the shelving in order, tell staff what to put where: well that seems fair, you have to have some criteria, cookery books for example, gardening etc, but then again . . . are cookery and gardening books not also examples of ‘creative nonfiction’? And what about ‘Poetry’?

To be continued, ad infinitum . . .

Landscape with Beggars

Landscape with Beggars

Juan Manuel Roca

The good people wonder

Why a tattered rabble of beggars

Block their prospect of the lilies.

If they don’t receive their ration of manna,

It’s due to their savage custom

Of blighting the landscape and the view.

More ancient than their profession

The beggars emerge from ancient catacombs

Or from remote cathedrals that raise their domes

Between hospices and hospitals.

As they go by they wound and poison the landscape

And the people give way at their passing

As if they were parting a sea

Which they stain with taunts and devastation.

A procession of smells and a procession of dogs

Go past with the wretched hordes. Town mayors

Watch them with watery eyes

While spooning out soup as thick as lava.

The priests seek them out like food

From a kingdom in another world

And describe to them the quarries of hell,

Although they seem to have lived there forever.

They are of another race, another country,

The beggars are dark strangers

Who live on the invisible frontiers of language.

Between them and us a coin makes mock,

A dark commerce in scarcity

Beneath the trinket shop of a relative of God.

On festive days they stare at phantom ships:

They extend their bowls and rough beds to no one

And in the atriums they only pile up scraps of miracles.

There is something of the scarecrow about their trade

Something of falconry about the eyes,

In the way they look at the doves’ bread.

A drunk and downcast man told me at the exit to the bar:

They could send them off to war, to serve as barricades.

The beggars don’t know where to go

When we are ordered to confine the wounded shadows.

The tourist guides, so as not to worry travellers,

Inform them that the beggars are extras

For a film being shot on the streets.

Perhaps they have emerged from a bad dream, from a factory,

From a dockside, from a mine, from a squat.

From the bad dream they bring the surly gaze of those who flee,

From the factory they retain the complexion of a prisoner,

From the docks the vice of loading bales of nothing,

From the mine hard and aggressive eyes,

From the squat an echo carried from the land of Nobody.

Ridicule and Mockery, two faithful dogs, are their companions.

This translation by Richard Gwyn first appeared in Cyphers Magazine, Ireland, 2014.

Juan Manuel Roca (b. Medellín, Colombia, 1946) is one of the most widely read and respected figures in contemporary Colombian poetry. A successful journalist and social commentator, he has a long association with the world-famous poetry festival in the city of his birth, set up in defiance of the long years of war and civil strife in his country. He has received numerous awards, including the prestigious Spanish prize, Casa de Ameríca de Poesía Americana 2009, for his collection Biblia de Pobres, from which ‘Paisaje con mendigos’ is taken.

Paisaje con mendigos

Las buenas gentes se preguntan

Por qué los mendigos interponen,

Entre sus ojos y los nardos,

Su amasijo de harapos. Si no reciben

Su cuota de maná es por su feroz costumbre

De llagar el paisaje y la mirada.

Más antiguos que su oficio,

Los mendigos vienen de antiguas catacumbas

O de remotas catedrales que levantan sus cúpulas

Entre hospicios y hospitales.

Al cruzar hieren y enferman el paisaje

Y las gentes se abren a su paso

Como si partieran en dos un mar

Que tiñen de dicterios y quebrantos.

Un séquito de olor y un séquito de perros

Van tras las hordas miserables. Los alcaldes

Los miran con ojos acuosos

Mientras cucharean una sopa densa como lava.

Los sacerdotes los buscan como alimento

De un reino de otro mundo

Y les describen las canteras del infierno,

Aunque parezcan habitarlo desde siempre.

Son de otra raza, de otro país,

Los mendigos son oscuros forasteros

Que viven en las fronteras invisibles del lenguaje.

Entre ellos y nosotros una moneda nos escarnece,

Un oscuro comercio de penurias

Bajo la tienda de abalorios de un pariente de Dios.

Los días festivos escrutan buques fantasmas:

No encuentran a quien extender yacijas o escudillas

Y sólo amontan en los atrios migajas de milagro.

Algo de espantapájaros hay en su oficio,

Algo de cetrería en sus ojos,

En su manera de mirar el pan de las palomas.

Un hombre ebrio y compungido me dijo a la salida del bar:

Podrían mandarlos a la guerra, servir de barricadas.

Los mendigos no saben dónde ir

Cuando ordenan que acuartelemos las sombras malheridas

Los guías de turismo, para no inquietar a los viajeros,

Advierten que son actores de reparto

De una película que ruedan en las calles.

Quizá hayan salido de un mal sueño, de una factoría,

De un muelle, de una mina, de una casa usurpada.

Del mal sueño traen la mirada arisca de quien huye,

De la fábrica conservan un color de presidario,

Del muelle el vicio de cargar fardos de nada,

De la mina unos ojos duros y pugnaces,

De la casa usurpada en eco llegado de tierras de Nadie.

Escarnio y mofa, dos perros fieles, los acompañan.

What Gets Lost

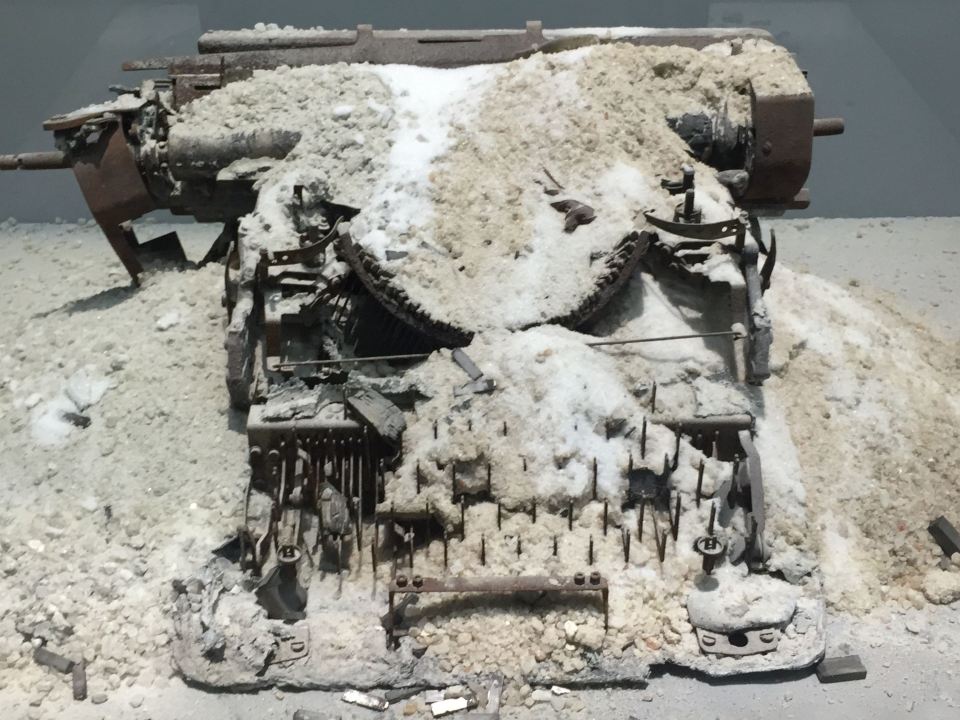

Typewriter, Anselm Kiefer

Few more irritating quotations are cited more frequently than Robert Frost’s famous old saw about poetry being ‘what is lost in translation.’ For the unconverted, and in honour of a recent re-reading of Reid’s poem in Edith Grossman’s excellent Why Translation Matters, here is Alastair Reid’s poem on the subject.

Incidentally, as if the ghost of Alastair were intentionally confounding the matter, there are two versions of this poem about the translation process: one can found in Grossman’s book (and which I reproduce below); the other, in the otherwise excellent Inside Out, edited by Douglas Dunn, contains variations in the English and typos in the Spanish. I am therefore going with the other. Both versions, needless to say, can be found online.

What Gets Lost

I keep translating traduzco continuamente

entre palabras words que no son las mías

into other words which are mine de palabras a mis palabras.

Y, finalmente, de quién es el texto? Who has written it?

Del escritor o del traductor writer, translator

o de los idiomas or language itself?

Somos fantasmas, nosotros traductores, que viven

entre aquel mundo y el nuestro

between that world and our own.

Pero poco a poco me ocurre

que el problema the problem no es cuestión

de lo que se pierde en traducción

is not a question

of what gets lost in translation

sino but rather lo que se pierde

what gets lost

entre la ocurrencia – sea de amor o de desesperación

between love or desperation –

y el hecho de que llega

a existir en palabras

and its coming into words.

Para nosotros todos, amantes, habladores

as lovers or users of words

el problema es éste this is the difficulty.

Lo que se pierde what gets lost

no es lo que se pierde en traducción sino

is not what gets lost in translation, but rather

what gets lost in language itself lo que se pierde

en el hecho, en la lengua,

en la palabra misma.

Alastair Reid (1926-2014)

Anselm Kiefer at the Pompidou

A couple of weekends ago we had the opportunity to visit the Anselm Kiefer retrospective at the Centre Pompidou in Paris. Quite apart from its power, scope and integrity – and in spite of its overwhelmingly dark subject matter – the exhibition filled me a similarly paradoxical and devastating faith in humanity that can be glimpsed in the work of Kiefer’s compatriot, W.G. Sebald. Kiefer, incidentally, was born one year after Sebald, on 8 March 1945, at the time of the massive allied air raids on his native Germany documented by Sebald in The Rings of Saturn and elsewhere. Much of Kiefer’s work reflects openly on the legacy of Nazism, a tendency that brought him intense criticism from German critics at the start of his career. As he himself has written:

‘After the ‘misfortune’, as we all name it so euphemistically now, people thought that in 1945 we were starting all over again . . . it’s nonsense. The past was put under taboo, and to dig it up again generates resistance and disgust.’

His undaunted gaze on the past of Germany – and Europe at large – struck me as overwhelmingly pertinent now, as Europe faces a humanitarian crisis in the shape of millions of refugees, and the German and European Right flexes in indignation, while in the United States Donald Trump begins to stir up the same kind of populist xenophobia that made the whole experiment of the Third Reich possible. However, Kiefer does considerably more than reflect on historical contingencies, and his oeuvre, massive in range as well as intellectual breadth, explores the idea of a collective mythology – not only the specifically Germanic, Romantic imagination with which much of his work is imbued – but the entire project of the human condition, and of how to live humanely under inhumane conditions, if that is at all possible.

I would need several months to reflect in depth on the emotions generated by this extraordinary exhibition. It is the third time I have visited a major Kiefer show, but the Pompidou have excelled themselves in the attention to detail and the fantastic range of work exhibited. Unfortunately, the exhibition only runs until 16 April, but if you have any chance at all of getting there, it is very much worth it.

I have chosen to consider reproductions from two of the most powerful paintings in the exhibition, titled Margarethe and Sulamith, a thematic that Kiefer has explored exhaustively following Paul Celan’s famous poem ‘Todesfuge’ (Death Fugue), concluding with the famous lines that reflect on the murder by immolation of the Jewish girl Sulamith (Shulamite in The Song of Songs) and contrasted with the golden-haired Aryan Margarethe, whose hair, represented in the painting by straw, according to Sue Hubbard in The Independent ‘symbolises the German love of land, and the nobility of the German soul, allowing Kiefer to play with complex notions of racial purity.’

According to Rebecca Taylor, ‘all of the canonical elements of Kiefer’s work’ are present in the painting Sulamith (or Shulamite): we find ‘a thick impasto resulting from a hardened mixture of oil, acrylic, emulsion, and shellac; a brittle, textured surface infused with commonplace materials (in this case, straw and ash); mythological or biblical references . . . and a historical subject or location (a Nazi Memorial Hall in Berlin).

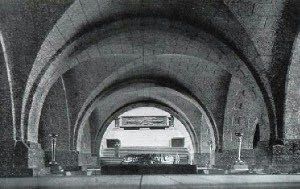

Wilhelm Kreis, Funeral Hall for the Great German Soldier (Berlin, 1939)

‘ . . . Kiefer’s hall is not a memorial to great men with patriotic flags waving boldly, but a gateway to damnation, a dark and foreboding road to hell, enclosed by low arches and paved with massive stones —the whole mise-en-scène . . . suggestive of an oven (immediately bringing to mind the hyperactivity of the crematoria at the Nazi death camps).’

Kiefer has stated that he would have liked to have been a poet – though it seems strange to me that an artist whose work is so imbued with its own poetry would consider language to be somehow a ‘higher’ attainment than that which he has achieved through his extraordinary visual creations. But it seems only appropriate to close with Christopher Middleton’s marvellous translation of Paul Celan’s poem ‘Todesfuge’, which inspired Kiefer in these paintings.

Fugue of Death

Black milk of daybreak we drink it at nightfall

we drink it at noon in the morning we drink it at night

we drink it and drink it

we are digging a grave in the sky it is ample to lie there

A man in the house he plays with the serpents he writes

he writes when the night falls to Germany your golden

hair Margarete

he writes it and walks from the house the stars glitter he

whistles his dogs up

he whistles his Jews out and orders a grave to be dug in

the earth

he commands us strike up for the dance

Black milk of daybreak we drink you at night

we drink you in the morning at noon we drink you at nightfall

drink you and drink you

A man in the house he plays with the serpents he writes

he writes when the night falls to Germany your golden

hair Margarete

Your ashen hair Shulamith we are digging a grave in the

sky it is

ample to lie there

He shouts stab deeper in earth you there and you others

you sing and you play

he grabs at the iron in his belt and swings it and blue are

his eyes

stab deeper your spades you there and you others play on

for the dancing

Black milk of daybreak we drink you at nightfall

we drink you at noon in the mornings we drink you at

nightfall

drink you and drink you

a man in the house your golden hair Margarete

your ashen hair Shulamith he plays with the serpents

He shouts play sweeter death’s music death comes as a

master from Germany

he shouts stroke darker the strings and as smoke you

shall climb to the sky

then you’ll have a grave in the clouds it is ample to lie there

Black milk of daybreak we drink you at night

we drink you at noon death comes as a master from Germany

we drink you at nightfall and morning we drink you and drink you

a master from Germany death comes with eyes that are blue

with a bullet of lead he will hit in the mark he will hit you

a man in the house your golden hair Margarete

he hunts us down with his dogs in the sky he gives us a grave

he plays with the serpents and dreams death comes as a

master from Germany

your golden hair Margarete

your ashen hair Shulamith.

Translated by Christopher Middleton

Angry in Piraeus

Flicking back through old photographs, I find one taken while returning from an evening out with friends in Istanbul, and passing some wooden-fronted houses in a twisting street, near the shore, that seemed to belong entirely to a world of things forgotten, specifically one of those nostalgic evocations of the old city invoked by Orhan Pamuk in his memoir Istanbul: Memories of City.

It was with real pleasure, then, that I read Maureen Freely’s bewitching essay in the Cahiers series produced by the American University in Paris, called Angry in Piraeus (the title is explained by Freely’s childhood memory of attempting, as a linguistically gifted nine-year-old, to moderate between her father’s splenetic discontent and an implacable Greek taxi driver). She evokes a scenario, familiar to some of us, of being caught between two angry parties and two sets of rules, and having to act as interlocutor between individuals who do not share a common language, and realising, of a sudden, that this is what all human communication is like, but more so. And the antidote? Freely describes what it might be for her:

‘ . . . If asked to describe paradise on earth, I would depict a city I have never seen before, a city I could wander through without anyone quite seeing me. A maze of narrow lanes would send me past gate after locked gate, courtyard after sunlit courtyard. In each there would be another drama, another cast of characters conversing in a language I was hearing for the first time, but that had existed for many millennia, and that I would now attempt to explore, word by word.’

A murmuration of starlings

Why do starling swarm in the sky? What are they communicating, if anything? Is it play? There doesn’t seem to be a clear response on any website I have searched.

But I have discovered that it is called a ‘murmuration of starlings’, which I like. It evokes the astonishing burr of all those wings in unison, which can be heard whenever you pass close to a group. The RSPB website says:

We think that starlings do it for many reasons. Grouping together offers safety in numbers – predators such as peregrine falcons find it hard to target one bird in the middle of a hypnotising flock of thousands.

They also gather to keep warm at night and to exchange information, such as good feeding areas.

They gather over their roosting site, and perform their wheeling stunts before they roost for the night.

The starlings I photographed through my car windscreen (I stopped the car first) were swarming over the flatlands of Ampurdan, near the fresh and saltwater marshes of the Aiguamolls reserve. But I find it hard to be convinced that they gather in this way to keep warm at night (especially as it was mild, and mid-afternoon), and nor am I convinced by the peregrine falcon theory (there are eagles here in the Ampurdan also) and the hypnosis effect on such birds of prey.

An article in The Guardian informs readers that The Society of Biology is calling on the British public to “help them solve the mystery of why murmurations form, how long they last and why they end.”

The Christmas and New Year break can be draining enough anywhere, but here in Spain the festive drudgery carries on until Epiphany on January 6th, and the celebration of the coming of the kings (Reyes, or Reis in Catalan), the Magi of the Orient who arrive to welcome the baby Jesus in his manger, surrounded by the traditional donkey, cow and a few sheep. This not only means that nothing functions for a full two weeks, but that everyone – especially those with small kids – are in a state of near exhaustion by the time they need to go back to work on 7th January. This puts everyone in a bad mood, even if the weather, and particularly the persistent icy wind, were not enough.

One aspect of the visitation of the kings, in almost every village across Spain, is that the custom of a white person ‘blacking up’ for the role of King Balthasar – supposedly an African king – continues despite mounting criticism of the practice. In fact, Madrid has abolished the custom altogether, choosing to use a ‘real’ black person in the role. Since in Madrid the spectacle is customarily enacted by three of the City Councillors, and – unsurprisingly – there are no black Councillors to be found, a professional actor was found. As the English language newspaper The Local reported:

The Spanish capital has decided to break with tradition – all in the name of diversity . . . King Balthazar will be played by a black actor from an African association based in Madrid, confirmed the director of Programs and Cultural Activities at Madrid City Hall, Jesús María Carrillo . . . “As well as being more professional it will be more representative: we are not just using any old actor from an audition . . . we want to connect with the cultural diversity of the city while also bringing a sense of professionalism to the parade because it is a huge event, in which it is a huge responsibility to step into the shoes of one of the three kings.”

The actors will be paid around €1,000 for the parade which will take place in central Madrid on the evening of January 5th. Madrid City Hall also confirmed that sweets will be handed out during the parade to children in the crowd but in a “more peaceful way”: during previous years’ parades several members of the crowd had their glasses broken by flying candies.

Well, so much for Madrid. Here in the Catalan hinterland, there were no such pretensions at political correctness, let alone ‘connecting with the cultural diversity’ of the region. Sweets were thrown most peacefully, and nobody’s glasses were broken. In a society where a good percentage of the agricultural workforce is composed of black Africans, it is a mystery why the ludicrous and offensive practice of ‘blacking up’ be allowed to continue, but there we are. No doubt if a thousand Euros were offered for the job, a volunteer would be found quickly enough.

Well, so much for Madrid. Here in the Catalan hinterland, there were no such pretensions at political correctness, let alone ‘connecting with the cultural diversity’ of the region. Sweets were thrown most peacefully, and nobody’s glasses were broken. In a society where a good percentage of the agricultural workforce is composed of black Africans, it is a mystery why the ludicrous and offensive practice of ‘blacking up’ be allowed to continue, but there we are. No doubt if a thousand Euros were offered for the job, a volunteer would be found quickly enough.

Last weekend was the Festival of the Olive in Espolla, a neighbouring village. Espolla is only a walk away through the vineyards, but always seems to me a much more exalted and organized sort of place than our lowly village: they’ve got a shop that opens all day, a butcher’s, a couple of restaurants. There’s even a bar.

Our neighbours, Joan and Juliette, ran a stall (pictured above) to sell their excellent wines and honey. As well as locals, the festival is popular with French market stall holders and day trippers (France is only fifteen minutes drive away on the back road). On display, along with the local wines and glorious dark green, fragrant, earthy mineral-rich oils, there were great rounds of cheese, wonderful freshly baked breads, baskets, wooden chests, wood-burning stoves and candy floss. A great outing on a fine day, after nearly an entire gloomy week of the tramuntana mountain wind.

The village of Espolla, in the Ampurdan

Mount Canigou, from Espolla