Etymology of vagabondage

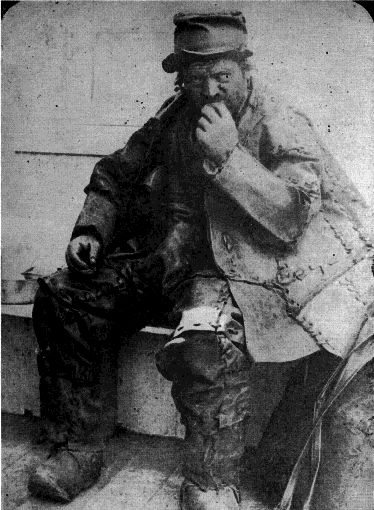

The Leatherman (ca. 1839–1889) was a vagabond famous for his handmade leather suit of clothes, who traveled a circuit between the Connecticut River and the Hudson River, roughly from 1856 to 1889.

Taken to task by a reader over the complicated etymology of vagabondage, I realise the need for another post on the subject.

In an earlier post I referred to the cirujas of Buenos Aires, otherwise known as cartoneros, those nocturnal seekers-out of trash bins, whose primary task is to find materials for recycling (plastic, cardboard, paper etc). Cartoneros are a sub-category of ciruja, a professional scavenger of all types of object for which a use or purpose can be made. That is why I likened the ciruja to a kind of street alchemist, seeking out base metal to transmute into gold. But I can see, as I was chided, that there is nothing especially poetic about this.

Whereas with the linyeras, there is. The definition of linyera given in my dictionary of lunfardo (Buenos Aires slang) is: “Persona vagbunda, abandonada y ociosa (idle), que vive de variados recursos (living off a variety of resources).” The word originally comes from the Piedmontese linger, which meant “a posse of tramps”. These fit the more romanticized notion of the classical vagabond, moving around the country (or the globe) without direction or purpose, usually associated in North America with the hobo, whose preferred means of travel was jumping trains, an occupation which was until not so long ago manageable in Europe also, but which has now become as obsolete as hitchhiking.

One still sees a posse of tramps drinking from bottles or flagons in any French town or city. These, of course, are clochards. A clochard or clocharde is a person “without fixed domicile, living from public charity and handouts.” The term clochard allegedly means ‘one who limps’ from the Late Latin cloppus (lame), but I have also heard that the term comes from the ringing of a bell (cloche) which in earlier times – when most cities in France were fortified – signalled that it was time for the indigent and poor, who could not afford lodging in town, to leave the city and go sleep in a field or a barn. To my mind, a clochard is somewhat different from a vagabond. A clochard might not venture from a known neighbourhood, while for a vagabond, the world is his lobster (sic).

According to French Wikipedia “Des vagabonds célèbres ont existé, par exemple Gandhi, Nietzsche, Lanza Del Vasto, et d’innombrables philosophes-vagabonds.”

To be continued. Any contributions welcome.

Facts about Things

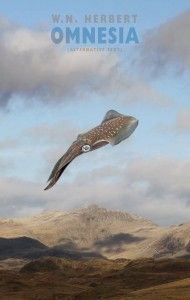

Omnesia, W.N. Herbert’s new collection of poetry, comes in two volumes, subversively titled Alternative Text and Remix, so as to disabuse the reader of any notion of an ‘original’. The word ‘omnesia’ is a conflation of omniscience and amnesia, the latter quality bringing into question the actuality of everything we know – especially, perhaps, our omniscience.

Omnesia, W.N. Herbert’s new collection of poetry, comes in two volumes, subversively titled Alternative Text and Remix, so as to disabuse the reader of any notion of an ‘original’. The word ‘omnesia’ is a conflation of omniscience and amnesia, the latter quality bringing into question the actuality of everything we know – especially, perhaps, our omniscience.

Herbert’s oeuvre is already varied and profuse, and this new collection is expansive in every way. The two volumes mirror and reflect upon each other, so that the airborne squid on the cover of ‘Alternative Text’ is flying towards the reader while the one on ‘Remix’ travels laterally – just as the author in the photo gazes amusedly to the right on the one book, and bemusedly to the left on the other. As an epigraph from Juan Calzadilla, tells us: ‘I have transformed myself into another / and the role is going well for me’. The concept of non-identical twin texts embodies, as the poet reminds us in his Preface, a rejection of ‘or’ in favour of ‘and’. A core of poems appears in both volumes, and the title poem opens ‘Alternative Text’ and closes ‘Remix’. But this sequencing does not signify a preferred reading order. Instead, we are warned off any kind of systemic coherence in the poem’s opening lines: ‘I left my bunnet on a train / Glenmorangie upon the plane, / I dropped my notebook down a drain; /I failed to try or to explain, / I lost my gang but kept your chain – / say, shall these summers come again, / Omnesia?’

Almost anything is a cue to Herbert, setting him off on one of his preferred riffs, especially our inescapable doubleness, exemplified by the two books – themselves containing other books which scurry off at tangents – and the frequent collusion of the narrative ‘I’ with other selves. In ‘Paskha’, the narrator sees a dead scorpion ‘in silhouetted crux’ and is ‘troubled by the brain’s chimeric quoins / its both-at-onceness, how the memory’s / assembled with our present self for parts . . .’ And it is this very both-at-onceness that has me riffling through the pages of ‘Alternative Text’ while reading ‘Remix’, following the demands of a connectivity which the poet’s Preface planted at the outset.

The poems take place in and meditate upon the poet’s journeys from Crete to the north of Britain, from Mongolia to Albania, from Finland to Israel, from Venezuela to Siberia, and among the poet’s several antecedents I was pleased to meet the shadow of Byron, especially in the ‘Pilgrim’ sequence. There is also a fine selection of poems in Scots.

The choice of epigraph usually serves as a pointer towards the poet’s intended direction. We are warned, in a quotation from Patricia Storace, that ‘In Greece, when you hear a story, you must expect to hear its shadow, the simultaneous counterstory.’ And not just in Greece. In ‘News from Hargeisa’, for instance, the counterstory of Somalia’s troubled history lies beneath every line, evoking local parable in the story of a lion, a hyena and a fox (animal imagery predominates in many of Herbert’s poems), as well as in the poet’s mourning of his friend Maxamed Xaasi Dhamac, known as ‘Gaarriye’, the late great Somali poet to whom both volumes are dedicated.

I am sure I missed subtle allusions and even whole thematic directions, and yet still enjoyed the poems I didn’t get. I did wonder how many people – outside of those who have lived on Crete – would ‘get’ ‘The Palikari Scale of Cretan Driving Scales’, a poem in which the driver’s recklessness is measured in direct relation to the magnificence of his moustache.

One might complain that there is simply too much in these books: not in the sense that they are lacking in editorial discretion, but that they demand a readerly imagination as febrile as Herbert’s in order to keep up. Is W.N. Herbert one person? I suspect not: and in any case he seems quite comfortable swapping costumes with his multiple others. I suspect also that Omnesia is a work one needs to live with for a while before appreciating all the shifts and mirrorings, puns and doublings, but even on a first acquaintance it offers richly rewarding reading.

Review published in Poetry Wales, Summer 2013 49 vol 1.

And nearly a year having passed since writing the above review, I can assure you that Omnesia repays revisiting. In so many ways.

Facts about Things

Things are tired.

Things like to lie down.

Things are happiest when,

for no reason, they collapse.

That French plastic bottle, still half-full,

that soft-back book, just leaning on

another book, drowsily:

soon they will want to go outside,

soon you will find them in the grass

with the empty bleaching cans and that part

of an estate agent’s sign

that’s covered in a fine grime like mascara.

That plastic bag you’ve folded up

feels constrained by you and wants

to hang from bushes, looking like a spirit,

sprawled and thumbing a lift.

Things are bums, tramps, transitories:

they prefer it when it’s raining.

Lightbulbs like to lie in that same

long, uncut, casual grass

and watch the funnel effect: the way

on looking up the rain all seems

to bend towards you,

the way the rain seems to like you.

Things which do not decay

like it best in shrubbery, they like

to be partly buried.

They like the coolness of the grass.

Most of all, they like it

when it rains.

A Vagabond

The gentleman depicted here is a vagabond, from the Latin vagari, to wander.

In English the term has almost disappeared in its original sense, although a quick internet search identifies the popularity of the term to help sell niche products, for example: a wine shop in London’s West End; a Swedish shoe manufacturer; an chic boutique in Philadelphia.

A Spanish Wikipedia entry on the word vagabundo (vagabond) begins like this:

“A vagabond is a lazy or idle person who wanders from one place to another, having neither a job, nor income, nor a fixed address. It is a type familiar from Castilian literature, which contains many examples of vagabond pícaros . . .”

In the dialect of Lunfardo, which originated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries among the lower classes of Buenos Aires, the term ciruja is applied to vagabonds who collect rubbish and sort through it in search of something useful. The term derives from the word for a surgeon, cirujano. Popular wisdom has it that these vagabonds were compared to surgeons because of the way in which they carefully sought out objects of interest, picking them from trash containers and municipal tips, rather than from inside a human body. This last attribute – the meticulous extraction of some unexpected treasure from amid the rejected dross of the everyday – seems rather fitting.

In French chanson, vagabonds are typically depicted as materially impoverished characters possessed of an irresistible allure. The singer Lucienne Delyle (1917-62), one of the most popular French singers of the 1950s (her greatest hit was Mon amant de Saint-Jean) also had a song called Chanson vagabonde, which can be heard here.

High Table

“These suppers take place once a week in the vast refectories of each of the different colleges. The table at which the diners and their guests sit is raised up on a platform and thus presides over the other tables (where the students dine with suspicious haste, fleeing as soon as they have finished, gradually abandoning the elevated guests and thus avoiding the spectacle the latter end up making of themselves) and it is for this reason rather than because of any unusually high standard of cuisine or conversation that they are designated “high tables”. The suppers are formal (in the Oxonian sense) and for members of the congregation the wearing of gowns in obligatory. The suppers do begin very formally, but the sheer length of the meal allows for the appearance and subsequent development of a serious deterioration in the manners, vocabulary, diction, expositional fluency, composure, sobriety, attire, courtesy and general behaviour of the guests, of whom there are usually about twenty.”

From Javier Marías, All Souls.

Thus begins one of the most hilarious and painful accounts of a certain kind of Englishness in all contemporary fiction, written, not surprisingly by a foreigner.

Thinking Pig

Stories of animal transformation abound in myths and folktales across the world. The theme is one that pervades Greek and Celtic mythologies, to take just two examples, and traditionally takes two forms: the ability of a god or sorcerer or shaman to wilfully transform him/herself into an animal; and the punitive transformation of people into animals for some misdeed or crime.

In a reading of Kafka’s Metamorphosis we might argue – as Nabokov does in his lecture notes on the book – that before the actual transformation, Gregor Samsa already lived like an insect, always scuttling about and kowtowing to greater pressures such as familial guilt and responsibility as well as a servile sense of duty to his job. Just as bugs mooch about, busying themselves yet at the same time achieving nothing, Gregor scuttles through his day, occasionally running across another insect and eating morsels as he finds them.

But what of the broader, mythical background to the notion of metamorphosis? In The Odyssey we encounter Proteus and Circe. Proteus changes forms several times throughout the poem: lion, serpent, leopard and pig, and ultimately is the character responsible for guiding Odysseus home. Circe’s ability to transform Odysseus’ crew into pigs might be regarded as the forerunner of countless tales of human-animal metamorphosis.

A powerful motif running though both Irish and Welsh mythic literature is that of shape-shifting . . . In the Welsh narratives, shape-shifting is generally presented as punitive rather than voluntary: a few episodes revolve around the transformation of people into animals because of some misdemeanour. Thus in ‘Culhwch and Olwen’, Twrch Trwyth – an enchanted boar – is the object of one of Culhwch’s quests to win the hand of Olwen. When questioned as to the origin of his misfortune, Trwch Trwyth replied that God blighted him with boar-shape as punishment for his evil ways. In the Fourth Branch of the Mabinogi, Gwydion and his brother Gilfaethwy are turned into three successive pairs of beasts (deer, wolves and swine) because of their conspiracy to rape King Math’s virgin footholder Goewin (Math needs a footholder – obviously – because he will die if his feet are not held in the lap of a virgin).

The pig seems a popular incarnation for errant humans. In Christian symbology they represent venality and the sins of the flesh. But there is more. In Edmund Leach’s famous paper on animal categories and verbal abuse, we are reminded that what we eat is often analogous to whom we are normally expected to sleep with: for instance we don’t – in British culture – tend to eat dogs, and – analogously, according to Leach – we disapprove of incest. We do however eat domestic farm animals (pigs, sheep, chickens etc), which are bred for human consumption, a class of animal that Leach correlates to an intermediate rank of sociability: people whom one might meet socially, within a circle of acquaintances, and who serve as potential sexual partners. By extension, claims Leach, we don’t, as a rule, sleep with complete strangers (questionable, but let’s stick with the theory for a minute) – and accordingly we do not habitually eat exotic animals such as lions and crocodiles and elephants and emus (availability is an issue there, which kind of upsets the theory, but let’s not be pernickety). Leach’s thesis could be summarised in less scholarly terms as the edibility : fuckability theory.

Having just read Marie Darriussecq’s Pig Tales, the English translation of a book originally published in French in 1996 as Truismes, I will concede that pigs are not regarded favourably. The protagonist of this excellent short novel has the misfortune to find herself metamorphosing into a sow and there is little she can do about it. She puts on weight in all the wrong places, her skin turns tough and bristles of hair sprout abundantly. She starts eating flowers and develops a love of raw potatoes. She grows a third nipple, then a full set of six teats. She grunts and squeals uncontrollably and eventually finds it more comfortable to go about on all fours. Darriuessecq’s book is hilarious and filthy and thought-provoking, tackling big themes such as consciousness, gender roles and the objectification of the female body, but it would be a shame to encumber it with too much interpretation. Sometimes a novel can be read like a dream (or a nightmare) and just taken for what it is: a woman morphing into a pig (just as her lover morphs into a wolf). The concept itself is enough to travel with: just think pig. Relax. Lie back in your sty. Make a bacon sandwich. Read a book, why don’t you.

Killing your darlings

For the past few years, whenever people ask me the dread question of ‘what are you working on’ I have mumbled something about a novel called The Blue Tent. The truth is, I have been writing TBT, on and off, since 2006, although the process has been interrupted by other projects, including a memoir and a couple of volumes of translation. However, the writing and completion of the novel has always re-emerged as a pressing need, like an addiction, or (I imagine) a particularly demanding affair with a psychotic lover. I had to get the book done. I needed to have completed another novel (note the pseudo-retrospective quality of this thought). I finished the first full draft in September 2012 and have been revising, when time allows, ever since. The Blue Tent became my secret life. My closest friends even knew it by name, but none of them had read a word of it. I became irritable when not working on it, and fractious when I was. At times I would resort to talking the book up: writing it, I told myself, I would discover what kind of a writer I really was: it would even, after a fashion, make me whole.

The Blue Tent started out as a modern fairy tale about the attempt of an individual to understand the weird and incomprehensible events that begin to overtake his life after a tent appears in the field next to his house. But in the end the activity of writing the novel became contiguous with the inability of the protagonist to act within the story; his torpor began to mimic my own. It was a mess.

Yesterday, in the early hours of New Year’s Eve, I was lying awake, as so often occurs, pondering yet again the structural perversions wrought by the unruly novel, and I realised, after an hour and a half of twisting and turning, that I would have to get up and write things down. This is a familiar pattern. At a quarter to five I made tea, and then ascended to my study in the loft.

But this time, rather than work on the novel, I read through the notes I had made on it over the years and realised that the book was fucked. FUBAR. I didn’t love the story any more; the characters didn’t interest me (and even if they interested other people, I was not inclined to keep working with them); the premise was interesting but essentially it was just an idea that could have been developed in any one of a thousand ways. The way that I had chosen to develop the idea had brought me to a dead end, and I was stuck. The feeling in my gut told me, without hesitation: Stop it, just Stop.

Feeling a little dizzy at the ease with which I had reached this decision (such moments come with the force of a revelation, even if, when you think them over afterwards, the thought has actually been on a slow burn for months, or even years) I googled ‘abandoned novels’ and the first article to come up was Why Do Writers Abandon Novels? – by Dan Kois in the New York Times. It begins as follows:

“A book itself threatens to kill its author repeatedly during its composition,” Michael Chabon writes in the margins of his unfinished novel Fountain City — a novel, he adds, that he could feel “erasing me, breaking me down, burying me alive, drowning me, kicking me down the stairs.” And so Chabon fought back: he killed “Fountain City” in 1992. What was to be the follow-up to his first novel, The Mysteries of Pittsburgh, instead was a black mark on his hard drive, five and a half years of work wasted.”

I felt better already. Schadenfreude. I hadn’t wasted that long. Not five and a half years. Not really. I’d written 60,000 words and done numerous drafts, some of them longer, but Chabon had written 1,500 pages, and was probably working on it full time.

Kois’ article surveys a number of writers’ views and experiences of abandoning a novel – or rather, putting it out of its misery. If something is making your life a misery, “erasing” or “burying you alive”, isn’t it merely an instinct for survival to kill it before it gets you?

Stephen King (as so often) had useful advice on the topic: “Look, writing a novel is like paddling from Boston to London in a bathtub,” he said. “Sometimes the damn tub sinks. It’s a wonder that most of them don’t.”

And then of course, while acknowledging that the book is not turning out as you might have wished – feel it sinking, to follow King’s analogy – you start making compromises with yourself. If you have a publisher and agent waiting for you to deliver, the pressure is on. You begin looking for arguments to convince yourself to let the book go, to just finish it, find a vaguely unsatisfactory resolution (one less unsatisfactory than all the others), publish it – if anyone wants it – and be damned.

But this is not an option. It would plague me forever to let a book go out in that state. While, on the other hand, the sense of liberation that has accompanied the killing of my darling is something to be cherished. This ‘failure’ feels, in fact, nothing like failure at all: it feels like being unchained from a madman.

In the meantime I will take Samuel Beckett’s advice, and learn to fail better next time.

Santa Hemingway

I was walking past this bar, called Revolución de Cuba in Central Cardiff (but seriously), when I spotted this sandwich board on the pavement advertising the venue with a picture of Santa Claus, which on close inspection bore a striking relationship to Ernest Hemingway. The only difference being that rather than bearing the gloomy, withdrawn, rather terrified features of Hemingway’s last couple of years on earth, this guy is looking really cheery. Like Santa Claus, in fact. Except that he’s Hemingway. Maybe.

I wonder how many of the winners of the annual Ernest Hemingway look-alike contest, held in Key West, Florida, actually resemble Father Christmas as much as, if not more than the man who in 1936 battered Wallace Stevens (a man twenty years his senior) to the ground in the rain in that same resort. Stevens, incidentally, did not look remotely like Santa Claus.

Which raises an interesting proposition: rather than have a look-alike contest, wouldn’t it not be more interesting to have an Ernest Hemingway/Santa Claus look-unalike contest? Sticking to males only (for the sake of simplicity) I would nominate Charles Hawtrey. Or Michel Foucault, neither of whom look remotely like the Hemingway/Santa Claus amalgam.

Crossing Patagonia

Writers Chain tour of Argentina & Chile, continued:

After three days of readings, lectures and tea parties in Puerto Madryn, Gaiman and Trelew, yesterday we made the long trip across the Patagonian meseta to Trevelin, in the foothills of the Andes. We travelled in two cars, laden down with suitcases, snacks and literary confabulation. Our car was driven by Argentinian anthropologist Hans Schulz and contained myself, Jorge Fondebrider and Tiffany Atkinson. We endured two punctures, the first in the middle of absolutely nowhere, the second after dark on the outskirts of Esquel. The first puncture proved problematic as we could not remove the tyre despite our manly efforts. We flagged down a truck, driven by a local farmer, Rodolfo, who kindly took Tiffany and myself to the small settlement of Las Plumas, where we had arranged to meet the other vehicle, driven by Veronica Zondek, and with instructions to find a mechanic, or at least to borrow the right tools from the garage there. Having acquired these, a relief party (Zondek and Aulicino) was sent back to the stranded Schulz and Fondebrider, and the flat tyre changed, while the contingent of Welsh poets and our coordinator, Nia, waited in a roadside canteen and ate empanadas and pasta.

During the rest of the journey across the prairie, the landscape began to change. The endless flatlands of sparse bush began to erupt into extraordinary outcrops of sandstone, stalagmites of sharp russet pointing skyward, or else solid slabs of sediment rising against the backdrop of an enormous sky, across which were layered fabulous accumulations of cloud. We arrived at Trevelin at midnight, where the hospitable proprietors of the Nikanor restaurant served us leek soup and homemade ravioli, washed down with an organic Malbec wine. Around us, the snowcapped mountains provided the sensation of having arrived in a place encircled by sleeping dragons. The casa de piedra, our hotel, is done up like a Tyrolean ski lodge, with a huge fireplace in the lounge, and carved wood furnishing. We slept the sleep of the just.

Two hours into the journey we had a flat. Nearest settlement, Las Plumas, 50 km away. We were, in fact . . .

Montaigne’s Tower

‘Habit’ according to Samuel Beckett, ‘is the ballast that chains the dog to his vomit’: and it is precisely what Montaigne seeks to uncover and dismantle in his essays. He does this in various ways, but one of his favourites is to run through apparently marvellous and diverse customs from distant cultures in order to convince his readers that what they take for granted is only a matter of what they are accustomed to. As he himself put it: ‘Everyone calls barbarity what he is not accustomed to.’ His essay ‘Of Custom’ discusses, by turn, the question of whether or not one should blow one’s nose into one’s hand or into a piece of linen; how in a certain country no one apart from his wife and children may speak to the king except through a special tube; how in another land ‘virgins openly show their pudenda’ while ‘married women carefully cover and conceal them’; how in other (unspecified) locations the inhabitants ‘not only wear rings on the nose, lips, cheeks and toes, but also have very heavy gold rods thrust through their breasts and buttocks’; how in some nations ‘they cook the body of the deceased and then crush it until a sort of pulp is formed, which they mix with wine, and drink it’; where it is a desirable end to be eaten by dogs; where ‘each man makes a god of what he likes’; where flesh is eaten raw; where they live on human flesh; where people greet each other by putting their finger to the ground and then raising it to heaven; where the women piss standing up and the men squatting; where children are nursed until their twelfth year; where they kill lice with their teeth like monkeys; where they grow hair on one side of their body and shave the other. By blasting his reader with these numerous examples of apparent strangeness, Montaigne makes them question the practices which they habitually regard as unquestionable and normal in a new light. Indeed, he raises many of the issues that cultural anthropology began to tackle four centuries later, and he can safely be regarded as an early relativist. When he had the opportunity to speak with some American Indians from Brazil, the Tupinambá tribe, of which a delegation was brought before the court at Rouen, he was not simply concerned with ‘observing’ them, as though they were rare specimens of primordial life: he was much more interested in recording their amazement at their French hosts. The observers observed.

Of paradise and serpents

I don’t want to give the impression that a reading tour of the Antioquia region of Colombia is a picnic, as there are workshops to be given, schoolchildren to speak to about the arduous apprenticeship and perils to be overcome when embarking upon the writing life, interviews with zealous journalists to carry out; but yesterday’s visit to the colonial town of Santa Fe de Antioquia was a true pleasure. Apparently it is a popular tourist destination, but I didn’t see any. So what follows is a purely touristic and pictorial post, intended for family and friends, without any literary qualities at all.

I was accompanied on my reading by a Colombian poet, a Mexican poet, our Colombian presenter and my charming reader, Santiago Hoyos. The reading was attended by the good solid folk of Santa Fe, who particularly appreciated a poem of mine that makes mention of the Virgin Mary, and loudly applauded every poem that made mention of God (even when used ironically) by my Colombian collegaue, who goes by the splendid name of Robinson Quintero, pictured below, with arms and legs akimbo (there’s a word you don’t hear very often these days). I was touched that shortly after arrival we were presented with a fruit cocktail drink, made of watermelon, mango and pineapple, with a dollop of strawberry ice cream, the kind of thing that used to be called a knickerbockerglory. Mouthwatering. We were driven in a moto-taxi (a kind of lawnmower, with a bench for passengers) down to the Puente de Occidente, a famous bridge over the River Cauca, constructed by the engineer José María Villa (b. 1850), a local lad made good, who won a scholarship to New Jersey Institute of Technology and assisted in the building of the Brooklyn Bridge. José María Villa never quite managed to oversee the entire building of the Puente de Occidente as he was (as the Spanish Wikipedia entry has it) ‘carried away by alcoholism’ and his German assistant saw the project through.

After our reading a delightful pair of chaps played Colombian folk songs for half an hour and then we all went off for dinner. The return trip late at night, in a very bumpy pickup truck was reminiscent of a passage from Kerouac, enlivened as some of the company were by an organically grown herbal product, and when the lights of Medellín appeared below us, after ascending from the valley of Santa Fe and then descending in hair-raising fashion from a pass in the high cordillera, it felt as though we had returned from another epoch, another world.

Over lunch today the Colombian poet Juan Manuel Roca asked me what my impressions had been of Santa Fe. I thought it was wonderful, I replied, a kind of paradise. Colombia is a land of many paradises, he said, but also of many serpents.