More mind manure plus Dylan Thomas

Here is someone trying to set up house under the bridge that runs between Tudor Street and Taff’s Mead Embankment in Cardiff, known – until the council decided to light it up in pretty colours – as Scary Bridge. Actually, my loyal readers will know that this bridge has already featured in Blanco’s Blog before – remember the swan in a bag story? But hang on a minute ….. how on earth are these big people going to fit inside this little house? And why is the man – who looks a little like Stan Laurel, or Rob Howley – wielding the roof in this ferocious manner? Really, I have no idea what is going on here, and that’s the way it should be. It kind of gives me space to improvise.

Sometimes don’t you just want to celebrate all the things you don’t know? Celebrate and give thanks for one’s own incalculable ignorance? What is this incapacity of the human brain to enter into and accept a blissful state of unknowing? After a day of meetings, in which colleagues (as one’s co-workers are nowadays known) struggle to trap mercury snakes, ceramic scorpions and slithering fat pandas, dissect, label and bottle them, so they can be sent to human resources and invested in an FTA progamme (subject to CPR approval), when I am surrounded by people pretending to know stuff that you wouldn’t want to know even if you were paid to know it, stuff that would bore the arse off blue-arsed monkeys, I return home with my head spinning, and in a state of vertigo. Am I exaggerating? Do other people share my feelings about meetings? Or is there simply an as-yet-undiscovered medical condition that specifically attacks the attendees of meetings at institutions of higher education (and no doubt elsewhere) whereby the victims are afflicted by a trance-like state with symptoms including torpor, displacement, excessive irritation (including itching) and possibly distemper (or does the last only affect dogs?). Why does my brain turn to jelly whenever we have a meeting at work? What is the purpose of meetings? Why is it whenever you phone people, there is someone at the other end telling you that the person you wish to speak to is at a meeting? Why can they never simply be having a chat in the next room, or taking a coffee break, or a dump? Why do people constantly lie about ‘being at a meeting’ in order to make themselves sound more important than they are? Who do they think they are fooling? And as for so-called real meetings, they tire a person out so. I almost always know less when I leave them than when I begin them and I usually feel as though my brain has been sat upon by a particularly well-nourished diplodocus to boot.

Finally, here – on display last week at the Dylan Thomas Centre in Swansea – is a picture of the suit that Dylan was wearing in the last week of his life, presumably including the day that saw the downing of the famous 18 whiskies, or however many it was. Who, other than a complete wanker, would count the number of drinks he was downing? I was always suspicious of that story. Not that 18 whiskies is a lot, considering. Anyhow, apparently Dylan borrowed the suit off some fellow called Jorge Fick in the Chelsea Hotel before going off and dying in it. ‘Borrowing’ clothes was one of DT’s preferred activities. He was always ‘borrowing’ shirts after puking all over his own, and as for underwear etc, etc. An ex-girlfriend’s aunt used to go out with Clement Freud circa 1950 and they bumped into Dylan whilst queuing for the cinema in Soho. Dylan, whom they knew slightly, tried to blag the price of a seat from them but they didn’t have enough money. On another occasion, turning up at an acquaintance’s house to bum money/drinks/smokes, Dylan was answered at the door by the owner, who said ‘Sorry, we’re entertaining.’ ‘Not very’, quipped Dylan. Boom boom.

Nice suit though.

A State of Wonder, Part Two: Johann Sebastian Bach’s Goldberg Variations and Glenn Gould

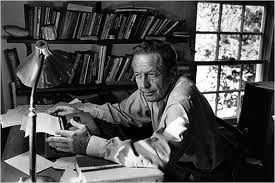

I have two recordings of Glenn Gould playing Bach’s Goldberg Variations on the piano. The first was made in 1955, the year before I was born, and the second in 1981, shortly before the pianist’s death, the same year that I left London and went to live in Crete. The second version is quite different from the first, and lasts several minutes longer. I think of the earlier recording as a day-time piece, and the second as nocturnal. They are both sublime, but in the first Gould is the young concert pianist on a mission, and he dazzles with his technical brilliance, his impeccable sense of timing. By the time he made the later recording he had nothing to prove, he had achieved everything a virtuoso pianist might reasonably be expected to achieve and more, and while there is no trace of complacency to the playing, it exudes a certain detached or entranced quality. Possibly the second version is more exacting, more profound, he lingers over the notes of the first variation with a confidence that is not to be confused with arrogance, a confidence that conveys a total acquaintance with, and mastery of, the music, a familiarity with every phrase, every musical innuendo, the fruit of years of study, and he is able to hover, and to hoist the listener into a space above and beyond the music, to linger there in a state of wonder, a phrase the pianist himself made use of. The album notes carry a quote from Gould: “The purpose of art is not the release of a momentary ejection of adrenalin but rather the gradual, lifelong construction of a state of wonder and serenity.”

I have two recordings of Glenn Gould playing Bach’s Goldberg Variations on the piano. The first was made in 1955, the year before I was born, and the second in 1981, shortly before the pianist’s death, the same year that I left London and went to live in Crete. The second version is quite different from the first, and lasts several minutes longer. I think of the earlier recording as a day-time piece, and the second as nocturnal. They are both sublime, but in the first Gould is the young concert pianist on a mission, and he dazzles with his technical brilliance, his impeccable sense of timing. By the time he made the later recording he had nothing to prove, he had achieved everything a virtuoso pianist might reasonably be expected to achieve and more, and while there is no trace of complacency to the playing, it exudes a certain detached or entranced quality. Possibly the second version is more exacting, more profound, he lingers over the notes of the first variation with a confidence that is not to be confused with arrogance, a confidence that conveys a total acquaintance with, and mastery of, the music, a familiarity with every phrase, every musical innuendo, the fruit of years of study, and he is able to hover, and to hoist the listener into a space above and beyond the music, to linger there in a state of wonder, a phrase the pianist himself made use of. The album notes carry a quote from Gould: “The purpose of art is not the release of a momentary ejection of adrenalin but rather the gradual, lifelong construction of a state of wonder and serenity.”

There are two photographs of the artist, taken in the respective years the recordings were made. In the first he is young, quite handsome even, or dashing, his hair flopping over his eyes, while in the later photo his hair has thinned and he is wearing glasses. In both pictures his concentration is almost palpable, and in both his mouth is open, not significantly, not gawping, but open, as though he was concentrating so hard that he had forgotten to close it, or had opened it to say something, and forgotten his lines – or to groan (his recordings are marked by these occasional groans, which should be disturbing, but are not).

Glenn Gould’s recordings of Bach keep me company for long hours, while I sit at my desk. He is a faultless companion, especially when I am struggling to impose order on my thoughts. I would like to catch some of the fallout from his playing, inform my own thought with some of that rigour, that clarity of intent, employ his music as a force-field against the fatigue that overtakes me as I type away, as a weapon against the viral dance, against the affliction of sleeplessness, in an inverse sense to the one in which they were first intended: for, ironically, Bach is supposed to have written the Goldberg Variations around 1741 to ease his patron, Count Keyserling’s nights of insomnia.

From The Vagabond’s Breakfast pp 133-4

Tom Waits, Leonard Cohen, Shane MacGowan, Charles Bukowski and all

Can you do a music review before listening to the music? Let’s see.

Yesterday I received through the post the new CD by Tom Waits, though I have not had the nerve to play it yet. I am not sure I even want to. I do not know quite how I feel about Mr Waits. There is an element of the showman about him that I don’t quite trust.

Unlike Mr Dylan, who can get away with the line “Me, I’m just a song and dance man” because he is so evidently much more, with Waits one might be forgiven for suspecting that such a self-diagnosis would be spot on. The talent is undeniable, and so is the musical range, the technical understanding and the skilful use of genre. The intense and earthy songs of heartbreak and loss on the album Heart attack and Vine once provided me with the perfect music to get miserably drunk to, alone and gloriously despairing, and there have been hundreds of versions of the same songs since. He does slow and sad and he does loud and fast. Both are good, though with the latter he does tend to shout.

I am willing to accept, perhaps, that my difficulty with Tom Waits is that I over-identified with his music for too long, and the problem lies with me rather than with him. And of course I cannot forgive the fact that he was never the real down-and-out he sang about (although he did sing about the lifestyle well). He is linked forever with Bukowski in the mythology I spun about myself in the 1980s (when I was in my twenties) and I cannot read a single line of Bukowski these days, I just find it laughable. Quite apart from his having a face like a jam doughnut. Waits and Bukowski, the dream team (though oddly, Bukowski’s favourite singer-songwriter was Randy Newman, who I liked in my teens but afterwards found rather tame). All these blokes, trying to prove how close to the edge they lived. Maybe I never took either Waits or Bukowski that seriously, they just summed up a lifestyle, but failed to go much deeper.

Shane MacGowan of course, he was another. Maybe he still is. Someone props him up every now and then and he stumbles onto a stage and sings a few songs in an increasingly incomprehensible and strangulated voice, but Christ he had a gift, as a songwriter if nothing else. I met him once, in a bar in Camden. I was always bumping into famous people when I was a drunk. He seemed a decent enough bloke, just fed up with the attention, enjoying a bit of quiet time, I could respect that. His songs with The Pogues became the anthems of my treks on foot across Spain towards the end of the eighties, just as Waits and Dylan had provided the lyrics of my hikes earlier in the decade, across Greece and Italy and France. Roberto Bolaño loved The Pogues too.

And what about Lennie? Leonard Cohen, I mean. I listened to him ardently when I was fourteen, fifteen, then went right off him until I rediscovered his music in my forties. I found out that his best songs can survive multiple replays in ways that Waits’ can never stand up to. And his concert at the Cardiff Arena a few years ago was one of the three best concerts (along with Lila Downs at Peralada and Mariza at Palafrugell) that I have seen in well, the last decade (and that includes two concerts by Dylan himself). I might have a Leonard Cohen song playing at my funeral – yes, I’ve thought about that, such is the dreadful urge towards oblivion, guided by Cohen singing, now which was it, ‘Dance me to the end of love’ or ‘Take this waltz’? I can never decide. Not that I’ll be listening.

But Tommo? He seems very together. Something that you could hardly claim for Cohen, whose biography I read a few years ago and who came across as terminally screwed up, for all the Zen stuff. Or maybe not. Maybe that is just an asinine remark, maybe we are all screwed up, and that part of Cohen’s beauty (and his charm) is that his pain has so indelibly marked him that we are touched, as it were, by the fall-out from his own menagerie of perfume, lace and broken violins, and we can sink into a delectable narcotic haze of suffering by proxy. Certainly the teenage girls in bedsits who were deemed to be his early audience were not alone. This teenage boy was spellbound through long nights with Songs from a Room. And, if I am honest, still can be. He offers just that much more: I’ll call it a flake of the ineffable, because it sounds kind of Cohenesque.

But as for Tom, my internal critic just won’t shut up. Blanco likes the songs, enjoys the ironic melancholy, loves the stuff about drunken sailors and jumping ship to Singapore – and, as an aside, in many of the songs from Rain Dogs, Waits’ best album to date, there are strong personal associations with Thomas Pynchon’s fabulous novel V. which, along with Burroughs’ Cities of the Red Night, was another of Blanco’s travelling companions from the 1980s – but he has problems incorporating Waits into the same illustrious hall of greatness at which Dylan and Cohen hold court. Maybe Blanco will stand corrected after a few listens of Bad as Me. I kind of hope so now. Will report back.

Birds of Sorrow

You cannot stop the birds of sorrow from flying overhead and crapping on your head, but you can stop them from nesting in your hair.

Faster than the speed of light

An article in the Guardian online alerts me to the fact that I am quite out of touch with things on a quantum level. It would seem that some wild Neutrinos have been identified speeding down the runway at Cern at sixty billionths of a second faster than the speed of light. Ah, the wee tearaways.

An article in the Guardian online alerts me to the fact that I am quite out of touch with things on a quantum level. It would seem that some wild Neutrinos have been identified speeding down the runway at Cern at sixty billionths of a second faster than the speed of light. Ah, the wee tearaways.

I can remember speeding down the road on holiday with my dad when I was about five with the window open and seeing the speedometer nudge sixty miles an hour and thinking that was fast.

But those Neutrinos would have left my dad’s old Zephyr standing. No, sorry, they would have arrived at the beach and come back to read me a story before I went to bed the night before.

The discovery, if validated, could turn Einsteinian physics on its head. I mean, the whole caboodle of special relativity will be up for grabs.

Which demands a replay of the Neutrino joke I saw on facebook the other night. “We don’t allow faster-than-light neutrino’s in here!” said the barman. A Neutrino walks into a bar.

That’s it. Terrible, I know.

So as not to get too left behind (geddit?) I have started following Matt Strassler’s blog, which contains a sort of ‘particle physics for idiots’ link, so I can pick up a few key phrases to bandy about next time I go down the local. A Neutrino walks into a bar. So they build this bar… Et cetera, ad infinitum.

Blanco’s Sunday Round-Up

I am leafing through a notebook and I find a terrifying quotation from John Cheever, and though I have no idea when I copied it down, it would seem to come from Cheever’s journals:

I am leafing through a notebook and I find a terrifying quotation from John Cheever, and though I have no idea when I copied it down, it would seem to come from Cheever’s journals:

When the beginnings of self-destruction enter the heart it seems no bigger than a grain of sand. It is a headache, a slight case of indigestion, an infected finger; but you miss the 8:20 and arrive late at the meeting on credit extensions. The old friend that you meet for lunch suddenly exhausts your patience and in an effort to be pleasant you drink three cocktails, but by now the day has lost its form, its sense and meaning. To try and restore some purpose and beauty to it you drink too much at cocktails you talk too much you make a pass at somebody’s wife and you end with doing something foolish and obscene and wish in the morning that you were dead. But when you try to trace back the way you came into the abyss all you find is a grain of sand.

Although reflecting a certain kind of mid century American machismo – ‘you make a pass at somebody’s wife’ – where the working day would characteristically end in cocktails, there is a truly awful angle to the idea that the tiniest thing, the smallest discomfort or inconvenience might send a person reeling into oblivion. How many times has that happened, and how many times have we told ourselves it cannot, must not happen again?

And that image of the grain of sand is so entrenched in our consciousness, because we are used to regarding the grain of sand as the minimal unit of matter (which, along with the speck of dust, it was before the advent of atomic physics) and we reduce every small beginning to just such a tiny item. ‘To see a world in a grain of sand’ according to William Blake’s ‘Auguries of Innocence’, is a familiar allegory to every armchair mystic.

And what Cheever is saying is not confined to the experiences of a recidivist drunk: it applies to anyone who has ever felt that quiet sliding out of control, the slow-motion disaster that the smallest, slightest disharmony begins to offset, and the offhand remark (or the not-so-offhand remark) the spillage, foot placed firmly in it, the unforeseen riposte, the fist raised, the threat made, the words that appal, the moment at which you take a step that cannot be retrieved, definitively.

Though, on the upside, that can be quite refreshing. Walking out on a job, while giving one’s boss an earful, might be the most gratifying thing that ever happens to some people.

Which brings us, in a roundabout way, to the economy and the leaders of Europe all mouthing off about how we must do this and can’t do that, and the demos in Madrid and Nueva York (with Naomi Wolf in her evening gown, for whom I can’t feel too much sympathy, although I agree with her in principle) and the poor Greeks at the end of yet another bollocking from the Germans, and meanwhile the bankers, the bastards who got us in this mess, all have their snouts back in the trough again as if nothing had happened.

Harrumph.

Which brings us logically to the rugby world cup final.

I never thought for a moment that the French would get ‘blown away’ in today’s match as Wales’ outstanding scrum-half Mike Phillips predicted in the heat of the moment after his team’s unlucky defeat in the semis. And on the day les bleus came good, playing more positive rugby than they have all tournament. I must confess, after indulging in a week of blatant francophobia, I was egging them on to score in that final onslaught before New Zealand regained possession of the ball. Maybe it was just a perennial desire to support the underdog. But it would have been a bitter irony for France to have walked away with the world cup, after losing to Tonga in the group stage.

So that’s done. It was all a bit of an anti-climax here in Cardiff, as everyone was rooting for a New Zealand-Wales final (and I had money on it). But despite losing to South Africa, France and Australia, the Welsh players have nothing to be ashamed of; in fact they done us proud.

Blanco is very much looking forward to the Wales-France match at the Millennium stadium next March, and will certainly be there, although he will not be dressed as a daffodil.

Borges and I

The idea that we contain a double, or a secret other, is a strangely pervasive one, and has fascinated writers from different traditions and in distinct genres. Among those who have famously approached the topic are Robert Louis Stevenson in The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, and Joseph Conrad in his long story The Secret Sharer. In Jorge Luis Borges’ short piece, reproduced below (in the translation Norman di Giovanni made with Borges himself rather than the travesty published by Andrew Hurley in the Collected Fictions) the writer focuses on the schism between the public persona of the famous writer Borges, and the individual, private Borges in whose first person the piece is written. Or is it that straightforward? While this is the apparent message of the text, we, the readers, are nonetheless engaging with it in the knowledge that it is written by Borges, the famous writer, so the dualism is in a sense perpetuated by that knowledge, driven by our relationship to Borges the writer rather than Borges the private individual. In the end, as Borges intended, we are faced with a hall of mirrors, in which Borges’ self-confessed tendency to falsify and magnify things (as do all writers of fiction) reaches into the very representation of the ‘I’ that claims to reject such things. We are all the products of an insidious dualism, the piece tells us, and to attempt to deny it only draws us deeper into the labyrinth.

The idea that we contain a double, or a secret other, is a strangely pervasive one, and has fascinated writers from different traditions and in distinct genres. Among those who have famously approached the topic are Robert Louis Stevenson in The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, and Joseph Conrad in his long story The Secret Sharer. In Jorge Luis Borges’ short piece, reproduced below (in the translation Norman di Giovanni made with Borges himself rather than the travesty published by Andrew Hurley in the Collected Fictions) the writer focuses on the schism between the public persona of the famous writer Borges, and the individual, private Borges in whose first person the piece is written. Or is it that straightforward? While this is the apparent message of the text, we, the readers, are nonetheless engaging with it in the knowledge that it is written by Borges, the famous writer, so the dualism is in a sense perpetuated by that knowledge, driven by our relationship to Borges the writer rather than Borges the private individual. In the end, as Borges intended, we are faced with a hall of mirrors, in which Borges’ self-confessed tendency to falsify and magnify things (as do all writers of fiction) reaches into the very representation of the ‘I’ that claims to reject such things. We are all the products of an insidious dualism, the piece tells us, and to attempt to deny it only draws us deeper into the labyrinth.

Borges and I

The other one, the one called Borges, is the one things happen to. I walk through the streets of Buenos Aires and stop for a moment, perhaps mechanically now, to look at the arch of an entrance hall and the grillwork of the gate; I know of Borges from the mail and see his name on a list of professors or in a biographical dictionary. I like hourglasses, maps, eighteenth-century typography, the taste of coffee and the prose of Stevenson; he shares these preferences, but in a vain way that turns them into the attributes of an actor. It would be an exaggeration to say that ours is a hostile relationship; I live, let myself go on living, so that Borges may contrive his literature, and this literature justifies me. It is no effort for me to confess that he has achieved some valid pages, but those pages cannot save me, perhaps because what is good belongs to no one, not even to him, but rather to the language and to tradition. Besides, I am destined to perish, definitively, and only some instant of myself can survive in him. Little by little, I am giving over everything to him, though I am quite aware of his perverse custom of falsifying and magnifying things.

Spinoza knew that all things long to persist in their being; the stone eternally wants to be a stone and the tiger a tiger. I shall remain Borges, not in myself (if it is true that I am someone), but I recognize myself less in his books than in many others or in the laborious strumming of a guitar. Years ago I tried to free myself from him and went from the mythologies of the suburbs to the games with time and infinity, but those games belong to Borges now and I shall have to imagine other things. Thus my life is a flight and I lose everything and everything belongs to oblivion, or to him.

I do not know which of us has written this page.

Rhys Ifans meets Voodoo Mama

I came across this diverting little ad (or spoof ad – I have no idea whether Voodoo Mama chilli sauce really exists: if it doesn’t, then it should) on Anthony Brockway’s always interesting blog Babylon Wales.

If you liked this, here is an even more hilarious real news report from Sky TV concerning Snoop Dogg (or Mister Dogg, as he is clepped in the clip) and one Ian Neale, a champion vegetable grower from Newport. Enjoy. And keep them coming please, Anthony.

Field of broken dreams

Here is the man who wrecked the rugby world cup, referee Alain Rolland, wearing his jersey of choice. The French team were utter shite. Sam Warburton’s tackle seemed, at worst, a yellow card. We were robbed of victory by bad refereeing and some unlucky place kicking, but the French were dire and in no way deserve to be world cup finalists. A ludicrous refereeing decision by the half-witted, half-French ref.

But look at this crewage who stopped off for a fag outside the Yoga club opposite The Promised Land. Do they look as if they are here for the yoga? Do they give a fuck? Should I? Should we? What a day. Oh fallen hopes. Oh crushed dreams. Blanco is bereft.

Scattergun Rant

This extraordinarily helpful poster can be found, not in a hospital or a school, but in the men’s washroom in the MALBA museum in Buenos Aires. I applaud the administrators of this institution for their interest in my personal hygiene. And we thought we had issues with the nanny state in the UK?

One thing I have never been able to abide is someone wagging a finger at me, or prodding said finger in my direction as they speak. There is a specific Porteño variant of this finger-wagging movement, which seems to comprise three sideways movements. A woman delivered it to me when I approached to ask a perfectly innocent question of her, imagining, I suppose, that I was about to ask her for money, or importune her in some manner. Do I look like a tramp? Do I look like some random maniac? Actually there is another explanation. Some people, on hearing a foreign accent, even if the speaker manages perfectly well to convey the sense of what they wish to say, simply freeze up. They go into a state of shock, as though their little brains send out a message: PANIC: FOREIGNER, followed by an utter failure to process language, as they are not listening to what you say because they are so distracted by the way you say it. I am certain there are other applications of this theory, and suspect it may be extended to many everyday life situations. As always, Blanco welcomes contributions on this theme.

How I loathe the casual conversations between travellers that one overhears in airport waiting areas, on ferries etc, the idiotic things people talk about in their quest to present themselves as accomplished globetrotters. I hope that doesn’t apply to me. But if it did, could I rant against myself? Probably.

Dancing man to man

Tango was danced between men from the very beginning, since it was considered too immoral for women, although clearly this is only a part of the explanation of man-to-man dancing, and a fuller account is given here .

I cannot vouch for its accuracy, but the site at least has some nice videos of men dancing with men.

The street where I took the photograph is the Calle Florida, which, apart from being the most famous street in the city of Buenos Aires, is closely associated with Borges and all things Borgesian – he lived nearby for many years and was frequently to be seen taking a stroll here. In fact a number of anecdotes about bumping into Borges take place in this street, which also boasts a version of Harrods, smaller than the one in Knightsbridge and currently closed down, but a famous landmark of the city. It opened in 1914 and closed in 1998, but has long been expected to re-open, subject to an extended lawsuit, following its acquisition by Swiss investors.

After taking a couple of pictures I was pursued down the street by a woman who was collecting donations for the dancing men. Since it is a common courtesy to give some money on such occasion, I was happy to donate the loose change I had in my pocket. The woman was clearly not impressed, and snarled at me: ‘is that all?’

What do you say to such a person? That the world is wicked; that dancing in the street never made anyone an honest crust; that we are all destined to be dust; that there is no afterlife? I despair. I continued on my way, to give my talk at the Translator’s Club, and answer questions on topics which, as always, I felt utterly unauthorized to speak about. But this is one of the hazards of being a person impersonator: your grasp of reality is frail and you often forget who it is you are meant to be impersonating; and although yesterday Blanco claimed to be the poet and translator Richard Gwyn, tomorrow he might just as easily turn into an extra from a Nazi zombie movie or invent a cure for hiccups.

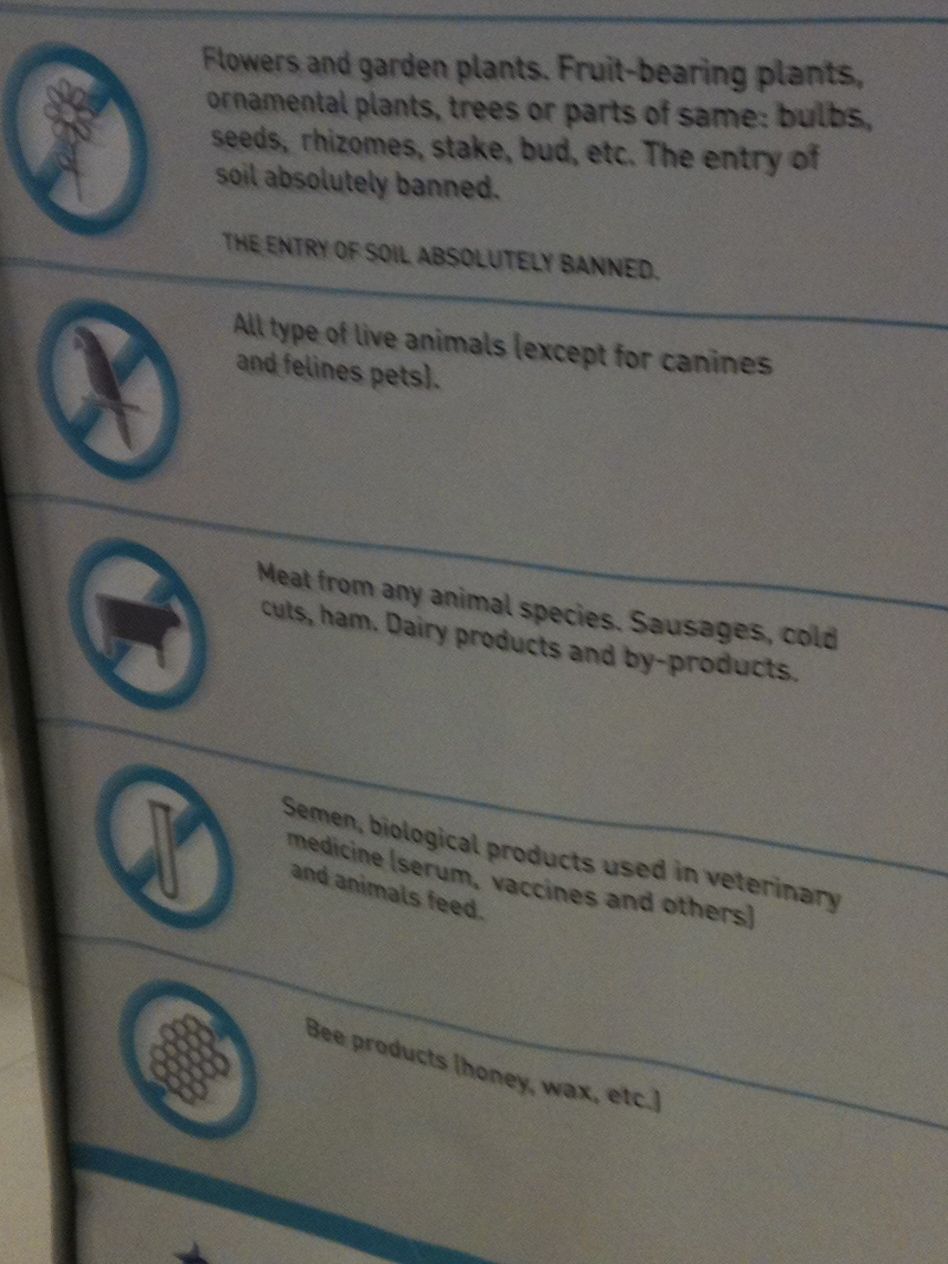

We don’t want your semen here thank you

Forgive me for the poor quality of the photo, but I was slightly concerned about taking pictures in the immigration zone of an airport, and used my phone. Here, if you can read them, are the rules about what you cannot import into Argentina. I draw your attention, gentle reader, (and if you blush, I will not see) to the item that prohibits the importation of semen. Now I am not the kind of person who would wander around from country to country with my pockets filled with test-tubes of spermatozoa, so I was not initially concerned, but then it struck me that most males visiting the country are carriers of semen, at least in its potential or unexpressed form, and should, if any sense of logic prevails, be prohibited from entering (how fraught with double entendre every word, every verb, suddenly becomes under these circumstances) the country at all, just to be on the safe side. But they let me in, and I promise I will be keeping my semen to myself.

I flew in – no, that gives the wrong impression of my physical attributes – I arrived on a British Airways Boeing 777, to attend a couple of literature festivals here, with the generous support of Wales Arts International. And I travelled Business Class, following an interesting exchange with the man who collected my boarding pass at Heathrow.

To start with, things were looking very peculiar at Terminal 5. The place was swarming with uniformed soldiers, who were clearly not in the service of Her Majesty The Queen. I picked out that they were speaking Spanish with Argentine accents long before going to the boarding gate. There were around fifty of them, wearing the blue berets of the United Nations. But what were they doing on a scheduled flight? Don’t they have their own planes? And when did you last see the uniformed soldiers of another nation state marching around in Blighty? Can’t have happened since the failed French invasion of Pembrokeshire in 1797.

Anyway, the soldiers were allowed to board first, along with the rich, the infirm, and the children. Then it was my turn. The man looked at a screen, told me to wait for a moment and then asked me if I was happy with the seat I had been allocated. I felt wary, as I had already, luckily, been upgraded to a seat in the more roomy Economy Plus (which I had not requested as I am not an MP but a responsible citizen who will not take advantage of public funds). So I certainly did not want him to take my seat away and plonk me amid a phalanx of Argentinian soldiers, however nice they might be. “Yes,” I said, “I am. It is an aisle seat, which I would prefer.” (I am a restless traveller). I hesitated. “Is that the right answer?”

“No, Mister Blanco” said the British Airways man: “That is not the right answer.” “Oh?” said, I, a little confused by his technique. “What, may I ask, is the correct answer?” He kept a straight face. “The right answer, Mister Blanco” he said, “is No, I am not happy with my seat. I would like another. You have an upgrade to Club World (starting price one-way £2699). Have a nice flight.” And he smiled, pleased with himself at his munificence. I acted cool (of course), as though travelling Club World was my natural due, and made my way onto the plane.

In Club World you have personal service and are ushered into a very comfortable seat inside a kind of cocoon with miles of leg room, and offered champagne or a soft drink to settle you in. Later, they bring you a menu, with a very appetizing range of dishes, and a wine list. I was planted between two beautiful young Argentinian people who I decided were a supermodel and a star polo player. Apparently in these circumstances you don’t greet each other or speak at all, except to order things. I tried hard to divine the correct mode of behaviour, while, of course, pretending that it was all second nature to me. I felt like an anthropologist on a field trip. I also sensed that for many of the thirty or so people in this luxurious compartment, a trip to Economy would provide similar challenges. I could easily imagine that close association with the plebian world – and the kind of person travelling economy to Buenos Aires is a far cry from your usual Ryanair type – would throw most of them into a fit of severe culture shock. Poor dabs.

When I had feasted on the beautifully prepared dinner, and declined the offers of this or that vintage beverage, the lights went down, the seat turned into a bed, and I lay in my little cubicle watching the film Hanna, about a sixteen-year old psychopathic killer with an elfin face, very untidy hair, and (it transpires) a heart of gold, sort of. Then I slept, which I hardly ever manage to do on long flights, for five or six hours.

The problem for me now, is that having tasted Club World, it is going to be a pain returning to Economy.

One day I will tell the story of the misogynist Rabbi and the appallingly drunken Ukrainian I had the pleasure of observing on another recent long-haul flight (in Economy), but it can wait.