Notes from a Catalan Village: The Mushroom Season

Autumn is the mushroom season, and at weekends, if you take a walk outside the village, you will encounter the mushroom hunter, a basket slung underarm, scanning the ground with an expert eye. King of the mushrooms is the rovelló, (Lactarius deliciosus) – pictured above, large and fleshy funghi that appear around the roots of pines, which grow abundantly along the tracks through the Alberas leading north and into France.

The picture includes one of the largest specimens I have ever encountered (or eaten). I’d recommend them cooked in olive oil or butter with some garlic and parsley, and spread over toast, or with spaghetti or linguine, if you have any.

Another – perhaps the other – defining feature of autumn is the Tramuntana – a wind that heads down off the Pyrenees and sweeps all before it. It makes its way to the coast of Menorca (200 miles due south from here), and who knows how far beyond . . . It is a wind invested with powerful psychological or emotional qualities.

This wind, the mountain wind, infiltrates every corner like a spinning incubus, growing inside each perception, every mundane act, taking them over utterly. Eventually you become aware only of the immediate and hallucinatory impact of whatever stands before you: the silent apparition of the dog waiting expectantly in the doorway; a dead sheep lying beside a roadside elm. The wind sucks out everything from you, leaving you exhausted and chastened. People have been known to commit murder on account of the mountain wind, or else go slowly insane over several seasons. (Colour of a Dog Running Away)

The wind needn’t affect everyone in quite this way; but the dogs, they notice, and flocks of starlings appear as you drive along the road to Garriguella and swerve and dive and bank away in a thick black cloud over the recently ploughed fields.

I have noticed, in myself and others, particularly after a full week of the wind – a tendency towards dreaminess or abstraction, a withdrawal into a state in which the structures of the phenomenal world have a tendency to dissolve. When this happens, conversations about the village take a strange turn, and the person with whom one thinks one has been speaking turns out to have been dead for a hundred years (the teenage girl who disappeared into the mountains with her illegitimate and stillborn child in 1912), and the postman mistakes you for Andreu the beetle-crusher, and the Butane delivery driver’s assistant refuses to let you take in the heavy gas cylinder that you use for cooking and hot water, mistaking you for the old man you must appear to him to be, and tells you to take care now, to wrap up warm, it’s cold.

Engrained confusion and Freudian typos

A porpoise with purpose

Are there words that you always seem to mis-type? I don’t mean mis-spell when writing longhand, but mis-type, when typing in a hurry, when the words are coming out faster than the fingers can organise them into print on the screen, and the mind, as it were, stumbles. Is there any point in analysing these moments?

The question I am getting to, rather clumsily, is whether or not there is an element of the ‘Freudian slip’ involved in the kinds of words that we habitually mis-type when typing faster than we can comfortably manage.

Let me give two examples. One word which I often type incorrectly is ‘purpose’. It occurs to me that this is because I lack purpose, that I have always lacked purpose. I am quite good on intention, and energetic in pursuing obsessive goals, but purpose can floor me. No doubt I spent too much time immersed in the novels of Samuel Beckett as a teenager, but I can hardly blame him. I over-identified with Beckett’s forlornly comic protagonists, mostly because, like my teenage self, they lacked purpose, and this coincided with a time in life when I and those around me were being encouraged to acquire and develop Purpose above all things.

Puprose or porpuse (which of course gets auto-corrected to ‘porpoise’)is how I spell it, and once or twice pusproe. I find it hard to ‘get’ purpose, and have to slow down, pause, and seek out the keys.

The other word I almost invariably type incorrectly is ‘because’ (becuase, beacuse, beacuase etc) – but most commonly beacuse .

My analyst friend, Alphonse, perched on his Freudian stool, says: purpose, sure, Blanco: you lack purpose. Because, surely, because you lack a sense of causality. You refuse to believe that one thing happens as a direct consequence of another thing, and prefer to follow your misguided and mystical faith in Sympathetic Magic.

And there’s the rub. Causality (or actually, I kid you not, cuaslity, which sounds rather like ‘casualty’ is as much of a stumbling block as ‘purpose’ and ‘because’ – the latter as a subordinating conjunction (I hate you because you are a liar) or compound conjunction (the concert was cancelled because of the rain). Either way ‘because’ is a concept whose very existence depends on an acceptance of causality.

But to reinforce this confusion, I have a final repeat slip-up to confess to: when speaking Spanish I consistently confuse the word casualidad (chance, coincidence) with causalidad (causality)– it is an engrained error, but one which must surely have deep psychological roots, in which I regard all causality as, essentially, a matter of chance or coincidence.

Dark Ages

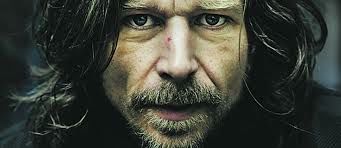

A new poem by Pedro Serrano, translated from the Spanish by Richard Gwyn.

DARK AGES

The tiger leaps

from a cloud of smoke into transience.

Falls on the devastating corral with an idleness

corresponding to the haste of his victims,

not to his elasticity.

He brushes past the bars of his cage

swinging his tail, rattling, tac, tac, tac, tac.

Crackling, he licks the circus sands

and raises ripples of dust,

traces of an approaching wake.

The motive for his observation

journeys in the smooth rhythm of his stomach,

velvety, gluttonous, elastic.

He turns circles before the spectators,

ears cocked, instincts fixed

on the excitement in the air.

He walks by the tables, propitious,

exudes substance and style.

The head sinks between the shoulders,

swells in the rail that encircles him.

The claws are extended

in the animal body that awaits him.

In the mirror of midday

the night’s end was taking shape,

beatific, inscrutable.

DARK AGES

El tigre salta

de la humareda a la fugacidad.

Cae en el aplastante corral con una pereza

que alude a la prisa de sus victimas,

no a su elasticidad.

Pasa rozando las rejas de su jaula

meneando la cola, golpeteando, taq’, taq’, taq’, taq’.

Restallante lame las arenas del circo

y levanta espejuelas de polvo,

huellas de una estela aproximándose.

La razón de su observación

viaja en el suave ritmo de su vientre,

afelpado, glotón, elástico.

Da vueltas a los espectadores,

las orejas prestas, su olfato

en la agitación que se respira.

Pasa propicio por las mesas,

se enjundia, se estiliza.

Sume la cabeza entre los hombros,

crece en el riel que lo circunda.

Deja las uñas puestas

en el cuerpo animal que lo acecha.

Desde el espejo del mediodía

se apuntaba el final de la noche,

beatífica, hierática.

Confabulation, or making shit up

Post is delivered erratically in the village, and two issues of the London Review of Books land in my letter box on the same day. I read one of them, and am struck by a sentence in an article by the excellent Jenny Diski, one of a series she has been commissioned to write following her diagnosis of terminal cancer (last year she was given possibly three years to live). The article – like much of her recent work – concerns her relationship with Doris Lessing, who ‘took her in’ as a troubled teenager, after ‘abandoning’ two of her own children in Rhodesia, as it was then known. The article begins with a troublesome quotation from Lessing, which is, in fact, the ‘Author’s Note’ to her book The Sweetest Dream:

“I am not writing volume three of my autobiography because of possible hurt to vulnerable people. Which does not mean I have novelised autobiography. There are no parallels here to actual people, except for one, a very minor character.”

In her essay, Diski explores and questions this (disingenuous) disclaimer, and edges towards a revelation of who the ‘very minor character’ might be.

‘What is she telling us about?’ asks Diski: ‘Sex, politics, her version of some truth that has been confabulated?’

And there it is. That word. Confabulate has a peculiar history. It comes from the Late Latin, confabulationem – “talking together”, con = with/together; fabula = fable, tale. The making of fables. And yes, you can do it in a group, with other people, or you can do it on your own, in your head. Making shit up, which is what writers do, a lot.

In recent years, ‘confabulate’ has taken on a specific medical meaning. I was very interested to learn that the clinical term for Alzheimer’s patients making shit up is ‘confabulation’. Wikipedia even has this: “Confabulation is a memory disturbance, defined as the production of fabricated, distorted or misinterpreted memories about oneself or the world, without the conscious intention to deceive” – which is kind of interesting, considering what it is that writers do. Now, if you look in any dictionary, you will find the word has become medicalised, thereby adapting its meaning to a specific clinical usage, while its original meaning has taken a back seat.

Recent neurological research (see, for example Daniel L. Schacter’s Memory Distortion) has provided overwhelming evidence to suggest that memories are constructed from an uneven mix of ‘fact’ and ‘fiction’. Something similar is true for perception: our perceptions are constructions that supplement data processed by the brain with other data that the brain supplies to fill in the blanks.

So, when Alzheimer’s patients ‘confabulate’, in other words ‘make shit up’, I cannot help but question what it is that writers do: the difference being, I guess, that with Alzheimer’s patients confabulation is involuntary, and with us it is (usually) intentional.

No ideas but in things

Since I began teaching creative writing, some fifteen years ago, I have become accustomed to the sad refrain from younger writers that although they fervently wish to write – or perhaps ‘become a writer’, which may or may not be the same thing – they don’t have anything to say.

It was with some pleasure, therefore, that I noted, during my leisurely (i.e. very slow) re-reading of Proust, the following passage:

‘. . . since I wanted to be a writer some day, it was time to find out what I meant to write. But as soon as I asked myself this, trying to find a subject in which I could anchor some infinite philosophical meaning, my mind would stop functioning, I could no longer see anything but empty space before my attentive eyes, I felt that I had no talent or perhaps a disease of the brain kept it from being born.’ (The Way by Swann’s, Lydia Davis translation).

But interestingly – at least for my purposes – the suggestion is made that the answer to his lack of inspiration might be found in the things around him, the very things, in other words, that are distracting to him:

‘ . . . suddenly a roof, a glimmer of sun on stone, the smell of the road would stop me because of a particular pleasure they gave me, and also because they seemed to be concealing, beyond what I could see, something which they were inviting me to come and take, and which despite my efforts I could not manage to discover . . . I would concentrate on recalling precisely the line of the roof, the shade of the stone which, without my being able to understand why, had seemed to me so full, so ready to open, to yield the thing for which they themselves were merely a cover. Of course it was not impressions of this kind that could give me back the hope I had lost, of succeeding in becoming a writer and a poet some day, because they were always tied to a particular object with no intellectual value and no reference to any abstract truth. But at least they gave me an unreasoning pleasure, the illusion of a sort of fecundity, and so distracted me from the tedium, from the sense of my own impotence which I had felt each time I looked for a philosophical subject for a great literary work.’

It is noteworthy here how Proust (through his young protagonist, Marcel) disavows any connection between these ‘objects with no intellectual value’, and his frustrated desire to write. For it is that very particularity, that sense of thingness (which always, as Proust suggests, is a cover for something else, something ineffable) that so often provides the starting point for a writer, if only he or she would look.

‘No ideas but in things’: the line by William Carlos Williams has been taken up as a mantra by teachers of poetry to students obsessed, like the young Marcel, with trying to convey deep philosophical concepts, and instead sinking in a morass of tired imagery, expressed through endless clichés of emotion and language.

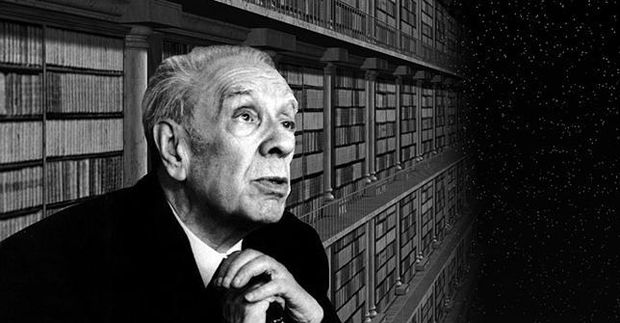

I think this is the notion I was trying to convey in my post of 29th August. You can simply be drawn in by some aspect of the inanimate world without knowing why. Not that everything is a metaphor, precisely, nor even that every object is a cover for something else (Borges reminds us that a stone might want just to be stone, a tiger a tiger), but that, using Ricardo Piglia’s thesis of the short story as an analogy, every account, every story conceals within it another telling, a secret story, and it is the quest for this other story that leads young Marcel, in his walks with his grandfather near the beginning of A la recherche du temps perdu to understand that this great, almost suffocating desire to be a writer – a desire that one observes (though perhaps in a less astutely articulated form) in many young students of creative writing who likewise find difficulty in finding subject matter to accommodate their ambitions – might encounter a solution by looking at ‘things’ in the world, rather than heading straight for the ‘idea’.

Finally, an insight from Jane Smiley, in her 13 Ways of Looking at the Novel, which drily sets to rest the maddening condition familiar to all writers of wanting to start a piece of writing, but managing to find any number of things to prevent them from doing so:

‘My definition of “inspiration” is “a condition of being stimulated by contemplation of the material to a degree sufficient to overcome your natural disinclination to create.”’

How long is a piece of string?

Or how long should a piece of writing be? Reflecting on this, in relation to a piece I am working on, I haphazardly check into an article in The New Yorker and am reminded by John McPhee that “ideally, a piece of writing should grow to whatever length is sustained by its selected material—that much and no more”. He is talking about non-fiction, but of course the same applies to poetry or to fiction: some might say it is even more crucial that fiction writers learn how to discern what length can be reasonably sustained by the selected material so as to avoid rendering the reader senselessly bored. Why, as Borges asked – and I often ask myself – succumb to the laborious and impoverishing madness . . . “of composing vast books—setting out in five hundred pages an idea that can be perfectly related orally in five minutes.”?

Or how long should a piece of writing be? Reflecting on this, in relation to a piece I am working on, I haphazardly check into an article in The New Yorker and am reminded by John McPhee that “ideally, a piece of writing should grow to whatever length is sustained by its selected material—that much and no more”. He is talking about non-fiction, but of course the same applies to poetry or to fiction: some might say it is even more crucial that fiction writers learn how to discern what length can be reasonably sustained by the selected material so as to avoid rendering the reader senselessly bored. Why, as Borges asked – and I often ask myself – succumb to the laborious and impoverishing madness . . . “of composing vast books—setting out in five hundred pages an idea that can be perfectly related orally in five minutes.”?

And while on the subject of contraction, here’s a lesson to learn about how to save time in storytelling by presenting several ideas at once. In Mavis Gallant’s short story ‘Grippes and Poche’, her protagonist, the solitary and sardonic writer, Grippes, witnesses a quartet of plain-clothes police beating up a couple of pickpockets, and escapes into a café. He has been out to collect some offal from the butcher’s to feed his cats. Rather than have Grippes ‘find’ his idea about realism – or ‘writing about real life’ – while seated at the café reading a newspaper; or even allowing the thought to present itself to him through internal monologue, reverie, or conversation with a literary adversary, Gallant allows her character to discover it on the newspaper in which the butcher has wrapped a sheep’s lung.

Returning on a winter’s evening after a long walk, carrying a parcel of sheep’s lung wrapped in a newspaper, he crossed Boulevard de Montparnasse just as the lights went on – the urban moonrise . . . Grippes shuffled into a café. He put his parcel of lights on the zinc-topped bar and started to read an article on the wrapping. Someone unknown to him, a new name, pursued an old grievance: Why don’t they write about real life any more?

Because to depict life is to attract its ill-fortune, Grippes replied.

And that ‘attracting of ill-fortune’, uttered to no one in particular by a man reading from a newspaper in which rests a sheep’s lung, while outside – in the ‘real’ world – the police exercise some casual violence on a couple of petty criminals, achieves a marvellous contraction of idea and imagery, without spoiling the effect by any explanation or commentary.

‘Stories can wait’: Mavis Gallant and taking your time over reading

I have taken my time reading the Paris Stories of Mavis Gallant, which is what she would have liked. But coming to the end of the book (in the elegant NYRB edition with Gallant’s own afterword) I am left with profound and persistent impressions.

The first is of a writer utterly committed to her craft. In her afterword she cites Beckett, who on being asked by an interviewer why he wrote, responded that he was ‘bon qu’a ça’ – no good at anything else. She herself wrote – as cited in Michael Ondaaatje’s excellent introduction: ‘Like every other form of art, literature is no more and nothing less than a matter of life and death.’

Gallant, who was born in Canada but spent most of her life in Paris, dying there last year at the age of 91 – achieves some remarkable things with these short stories, which largely describe the lives of Anglo-Saxon residents in Paris and on the Riviera during the 1940s and 50s. The finest of these, ‘The Moslem Wife’ and (especially) ‘The Remission’ manage to pull off the difficult task of presenting a story from the point of view of different protagonists – major and minor – with a seamless fluency, so that one barely notices the shift in free indirect style. Ondaatje comments neatly on ‘the ability to slip or drop into the thought processes of minor characters, without any evident signalling of literary machinery.’ The stories are populated by defiant, complex characters, who live and breathe within the reader’s imagination rather than sit inside the story as if placed there for the author’s convenience.

In ‘The Moslem Wife’ a young Englishwoman, Netta, is abandoned by her feckless husband, Jack, in their coastal home in the south of France just before the Second World War, forcing her to endure the hardships of the successive Italian and German occupations with her half-demented mother-in-law and a rabble of misfit neighbours. Here Gallant presents a succinct and poignant portrait of the wayward Jack, just before he leaves:

‘The plot of attraction interested him, no matter how it turned out. He was like someone reading several novels at once, or like someone playing simultaneous chess . . . At night he had a dark look that went with a dark mood, sometimes. Netta would tell him that she could see a cruise ship floating on the black horizon like a piece of the Milky Way, and she would get that look for an answer. But it never lasted. His memory was too short to let him sulk, no matter what fragment of night had crossed his mind. She knew, having heard other couples all her life, that at least she and Jack never made the conjugal sounds that passed for conversation and that might as well have been bowwow and quack quack.’

In ‘The Remission’ Alec Webb uproots from his life in England and goes to the south of France to die, but spends an unexpectedly long time doing so. The new Queen Elizabeth II is crowned and the family and neighbours gather to hear the radio transmission of the coronation. Still in his sickbed, Alec had ‘dressed completely, though he had a scarf around his neck instead of a tie. He was the last, the very last of a kind. Not British but English. Not Christian so much as Anglican. Not Anglican but giving the benefit of the doubt. His children would never feel what he had felt, suffer what he had suffered, relinquish what he had done without so that this sacrament could take place. The new Queen’s voice flowed easily over the Alps – thin, bored, ironed flat by the weight of what she had to remember – and came as far as Alec, to whom she owed her crown.’

Barbara takes a lover named Wilkinson, who wears a navy blazer and acts as unofficial chauffeur to the elderly expats on the Riviera. Gallant has the type off pat:

‘If he sounded like a foreigner’s Englishman, like a man in a British joke, it was probably because he had said so many British-sounding lines in films set on the Riviera. Eric Wilkinson was the chap with the strong blue eyes and ginger moustache, never younger than thirty-four, never as much as forty, who flashed on for a second, just long enough to show there was an Englishman in the room. He could handle a uniform, a dinner jacket, tails, a monocle, a cigarette holder, a swagger-stick, a polo mallet, could say, without being an ass about it, “Bless my soul, wasn’t that the little Maharani?” or even, “Come along, old boy – fair play with Monica!” Foreigners meeting him often said, “That is what the British used to be like, when they were still all right, when the Riviera was still fit to live in.” But the British who knew him were apt to glaze over . . .’ and later: ‘Most people looked on Wilkinson as a pre-war survival, what with his “I say’s” and “By Jove’s,” but he was really an English mutation, a new man, wearing the old protective coloring. Alec would have understood his language, probably, but not the person behind it.’

The subtleties of Gallant’s writing are not limited to her descriptive powers, nor to her portraits of men adorned with clipped accents and cravats, however. Not by any means. In both these stories the central characters, and major focuses of narration are the women who strive to make their lives work in spite of the men they are with, and the hardships they face through isolation, snobbery or simple loneliness. Towards the end of ‘The Remission’ the point of view shifts to Molly, Barbara’s daughter, as she attends Alec, her father’s, long-awaited death; and who at fourteen acknowledges, through observing her mother’s life, that ‘There was no freedom except to cease to love.’

Short stories like these – and several of them are not at all short – require time to read and savour. You cannot hurry through them, nor read more than a couple at a time, maximum. As Gallant herself writes in her Afterword: ‘Stories are not chapters of novels. They should not be read one after another, as if they were meant to follow along. Read one. Shut the book. Read something else. Come back later. Stories can wait.’

Information overload on the beach

There was a time when a beach was simply a beach. You took your clothes off, and if you were so inclined donned a bathing costume (or swimming suit) and splashed around in the sea. Upon exiting the waters, you might want to dry off – always bearing in mind the well-advertised health hazards – by basking in the sun. Even fifteen years ago that was all there was to it. Not now. Over the past few years, going to our nearest beach has turned into an educational and communicative experience in which we are alerted to:

- a map of all the beaches in the Llança municipality, and how to find them;

- a map of Grifeu beach, with accompanying symbology of all the activities encouraged, facilitated or prohibited thereon;

- the history of the beach, and fishing methods carried out historically in the zone;

- the etymology of its name: this is disappointing. Grifeu, we learn, is an old Catalan surname, but doesn’t tell us what the surname means. I want it to mean ‘Griffin’ but have found no evidence that it might.

- swimming routes encouraged by the municipal authorities, including an evening group swim at 7 pm each day following the buoys along the coast to Llança harbour, the so-called vies braves, or ‘brave routes’, not for the faint-hearted;

- a description of the tamariu (tamarix) tree that lies in the middle of the beach and under which cool shade may be sought; also informing us that the tamarix (or tamarisk) was the favourite tree of the Greek god Apollo;

- a monument to the Catalan poet Josep Palau i Fabre (1917-2008), and a sample of his verse concerning the beach itself, in recognition of the fact that the poet used to come here. (I once read alongside Palau i Fabre, already in his 90th year, at a local poetry festival, and was struck by his noble visage and penetrating gaze).

But does one need all of this on a visit to the beach? Information overload afflicts us everywhere we go, and quite frankly I don’t need it at the seaside. All this labelling, signalling, categorisation and the all-embracing bureaucratisation of everything, even so-called ‘leisure time’. Even poetry. Fortunately, however, one can just turn one’s back on it all and swim out to those buoys. At least out at sea there are fewer distractions.

Knausgaard’s Struggle, or How forgetting stuff can help you remember it more honestly

I have had Karl Ove Knausgaard’s work on my reading list for a while, particularly as some of the better critics have sung his praises (for example James Wood, writing in The New Yorker, or Boyd Tonkin, in The Independent). Now that I’ve read the first volume, dealing with his adolescence and the death of his father, I have to admit I’m a little bewildered at all the fuss. I don’t think I’ll be reading the second volume, in which he famously deconstructs his first marriage.

So much of Knausgaard’s story seems to be saying things simply to fulfil his own obsessive need to say them, to ‘record everything’. But he isn’t – thank god – ‘recording everything’; he is merely giving the spurious impression of thoroughness. I’m not convinced that much of it needs saying. It serves no purpose and is filled with tedious blather: ‘I dried my hair with the small towel’ . . . ‘I swallowed the last morsel and poured juice in my glass’. The ‘detail’ comes replete with set phrases and cliché: ‘I was as hungry as a wolf’ . . . ‘two sides of the same coin’, ‘seeing is believing’, etc. He piles on astonishingly boring reams of information, as though simply filling a page will do. Much of this book is typing, rather than writing, as though the author wanted to get the series of six volumes out as soon as possible – given his sales in Norway this might have been reasonable motivation. His work has received startling and adulatory comparisons with A la recherche du temps perdu. But Proust it ain’t.

There is some strong writing in the early pages when the author reflects on death in general and his relationship with his father (referred to throughout as a lower case ‘dad’) but the intensity of these opening pages is lost as we sink into the larger litany of the exhausting details of everyday life. Anyone who writes knows there is no such thing as ‘total honesty’: everything is, to a large degree, confection and elaboration, a weaving around or manipulation of some essential fragment of reality. There is not a writer alive who would claim to reproduce events from their own lives with a rigorous adherence to the truth because, as we all know, a writer can only ever present a version of events to the world: if you want to call that ‘corruscating truthfulness’ you’re welcome, but – as Bob Dylan once said – I don’t believe you, man.

Besides, as ‘Karl Ove’ confesses on page 387 of the Vintage edition: I usually forgot almost everything people, however close they were, said to me. This is an alarming confession, if we are being asked to consider the work as an example of corrosively truthful writing, or a “scorchingly honest, unflinchingly frank, hyperreal memoir” (The Guardian) – especially after 386 pages containing extensive tracts of dialogue with people who were ‘close’ to him. But perhaps ‘forgetting’ helps Knausgaard to remember in a more ‘honest’ way.

After a fashion, I can see this series of books as emerging from and resonating with the narcissistic tradition of Facebook and twitter, a constant attention-seeking and a wanting-to-be-noticed in a world in which everything is on display for all to see. Just as the young Karl Ove desperately needs, and fails to receive, his father’s attention. Knausgaard tells us he “wanted so much to be special” as an awkward teen who played in a heavy metal band (but dreamed of greater things, and had “the ambition to write something exceptional”).

It would be invidious to pick out one of the many examples of frankly bad writing in this first volume. Besides, I get it: I see what he’s doing with the self-consciously unedited prose style. But this thinly veiled autobiography (no, let’s stick with ‘novel’ – the old boundaries no longer count for anything) is not breaking new ground, as so many critics seem to be claiming. Apart from the strong opening and some isolated aperçus on death, it is pretty dull for the most part, with some legitimate seasoning of ‘profound thoughts’ edging their way in on occasion:

She glared at me. I swallowed the last morsel and poured juice in my glass. If there was one thing I had learned over recent months it was that everything you heard about pregnant women’s fluctuating and unpredictable moods was true.

‘Don’t you understand that this is a disaster?’ she said.

I met her gaze. Took a swig of juice.

‘Yes, yes, of course’, I said. ‘But it’ll be all right. Everything will be all right.’

And this description of rolling as fag:

I drained my drink and poured myself a fresh one, took out a Rizla, laid a line of tobacco, spread it evenly to get the best possible draught, rolled the paper a few times, pressed down the end and closed it, licked the glue, removed any shreds of tobacco, dropped them in the pouch [dropped what in the pouch?], put the somewhat skew-whiff roll-up in my mouth and lit it with Yngve’s green, semi-transparent lighter.

Does any of this matter? Who cares if the writer’s brother had a ‘green, semi-transparent lighter’? Who cares, even, what he dropped in the pouch. I cannot agree with James Wood’s assertion that “the banality is so extreme that it turns into its opposite, and becomes distinctive, curious in its radical transparency.” To my mind, the banality simply remains banal. And the writing, sloppy.

But perhaps I’m being unfair. Knausgaard clearly writes in a hurry, producing 10 to 20 pages a day, according to one account. Perhaps he should slow down a bit, do some editing even. But I guess it’s too late for that now. Or perhaps I should try again, and read him in a different way, accepting that, as Wood writes: “the writer seems not to be selecting or shaping anything, or even pausing to draw breath.” But then again, why should I? Life is short enough as it is, and I’d rather re-read Proust.

The relentlessness of his descriptions does serve a purpose, I’ll concede that: the deluge of ordinariness is meant to elicit in the reader a stronger consciousness of whatever we consider to be ‘reality’, but then again, this is all rendered with a naivety and dedication to ‘honesty’ that I find deeply suspicious. Maybe the resistance to – or outright rejection of – ironic detachment as a strategy in this writing is what I find most unsettling. For all the words, all the typing, there seems to be very little, if any, self-awareness here. And as with reality TV, I cannot quite take that world of written ‘reality’ seriously – especially when being asked to consider the ‘merciless frankness’ of an author who ‘can’t remember a single conversation’ – but who nonetheless has managed successfully to achieve that longed-for fame and specialness which he so craved as a teenager.

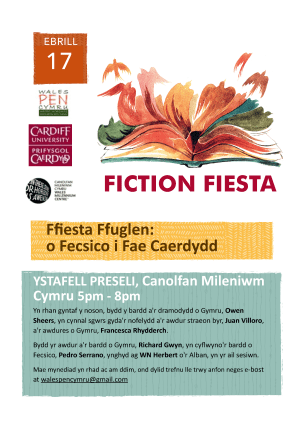

Fiction Fiesta 2015

PREVIEW | FICTION FIESTA 2015

This post also appears on the website of WALES ARTS REVIEW today. The new re-vamped Wales Arts Review serves as a media platform where a new generation of critics and arts lovers can meet to engage in a robust and inclusive discussion about books, theatre, film, music, the visual arts, politics, and the media.

To Reiterate

Lydia Davis, in inimitable style, consolidates the elements of reading, writing and travel in a short piece from her 1997 collection, Almost no Memory:

Michel Butor says that to travel is to write, because to travel is to read. This can be developed further: To write is to travel, to write is to read, to read is to write, and to read is to travel. But George Steiner says that to translate is also to read, and to translate is to write, as to write is to translate and to read is to translate. So that we may say: To translate is to travel and to travel is to translate. To translate a travel writing, for example, is to read a travel writing, to write a travel writing, to read a writing, to write a writing, and to travel. But if because you are translating you read, and because writing translate, because traveling write, because traveling read, and because translating travel; that is, if to read is to translate, and to translate is to write, to write to travel, to read to travel, to write to read, to read to write, and to travel to translate; then to write is also to write, and to read is also to read, and even more, because when you read you read, but also travel, and because traveling read, therefore read and read; and when reading also write, therefore read; and reading also translate, therefore read; therefore read, read, read and read. The same argument may be made for translating, traveling and writing.