Two poems by Claribel Alegría

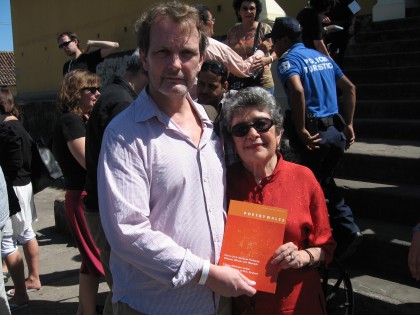

Claribel Alegría, who was born in Nicaragua in 1924, but raised in El Salvador, beginning a life of exile that included Chile, Mexico, Paris and the island of Mallorca, is a poet heavily influenced by the revolutionary struggles of the Central American peoples against the dictatorships of the middle and later parts of the twentieth century. She was closely associated with the Sandinista movement in Nicaragua, and after the overthrow of the Somoza regime, she returned to that country in 1985 to help in the reconstruction process (which has since gone so badly wrong under successive, corrupt regimes, including that of Daniel Ortega). In her assessment of the poet, Marjorie Agosín has written of the ‘multifaceted work of Alegría, from her testimony to her verse . . . In this woman’s furious, fiery, tender and lovesick words, the marginalized, the indigenous recuperate spaces, resuscitate their dead, and celebrate life by defying death.’ While many of the early poems focus on the revolutionary conflict, Alegría has also written numerous love poems, as well as novels and children’s stories. As a feminist, writing of the marginalized lives of Central American women, her work has emphasized the restorative power of collectivity and continuity.

Claribel Alegría, who was born in Nicaragua in 1924, but raised in El Salvador, beginning a life of exile that included Chile, Mexico, Paris and the island of Mallorca, is a poet heavily influenced by the revolutionary struggles of the Central American peoples against the dictatorships of the middle and later parts of the twentieth century. She was closely associated with the Sandinista movement in Nicaragua, and after the overthrow of the Somoza regime, she returned to that country in 1985 to help in the reconstruction process (which has since gone so badly wrong under successive, corrupt regimes, including that of Daniel Ortega). In her assessment of the poet, Marjorie Agosín has written of the ‘multifaceted work of Alegría, from her testimony to her verse . . . In this woman’s furious, fiery, tender and lovesick words, the marginalized, the indigenous recuperate spaces, resuscitate their dead, and celebrate life by defying death.’ While many of the early poems focus on the revolutionary conflict, Alegría has also written numerous love poems, as well as novels and children’s stories. As a feminist, writing of the marginalized lives of Central American women, her work has emphasized the restorative power of collectivity and continuity.

Towards the Jurassic Age

Someone brought them to Palma

they were the size of an iguana

and they lived off insects

and mice.

The climate suited them

and they began to grow

they moved on from rats

to chickens

and kept growing

they ate dogs

more than an occasional donkey

children left to roam the streets.

All the drains were blocked

and they turned to the open country

they ate cows, sheep

and kept growing

they knocked down walls

chewed up olive trees

rubbed their flanks

against protruding rocks

causing landslides

that blocked the roads

but they jumped over the landslides

and now they are in Valldemossa

they killed the village doctor

everyone was terrified

and ran away to hide.

Some are herbivore

and others carnivore

the latter have a kind of uniform

military caps that perch on their crests

but both sorts are dangerous

they wolf down plantations

and have fleas the size

of dinner plates

they scratch themselves against the walls

and houses fall down.

Now they are in Valldemossa

and they can only be stopped

by aerial bombardment

but no one can stand the stink

when one of them dies

and the people complain

and there’s no way

of burying them.

Letter to Time

Dear Sir:

I am writing this letter on my birthday.

I received your present. I don’t like it.

Always it’s the same old story.

When I was a little girl,

I would wait for it impatiently

I would get dressed up in my best

and go on the street to tell the world.

Don’t be stubborn.

I can still see it,

you playing chess with Grandfather.

At first your visits were infrequent;

very soon they became a daily occurrence

and Grandfather’s voice

began to lose its timbre.

And you would insist

and didn’t respect the humility

of his sweet nature

and of his shoes.

Afterwards you courted me.

I was just a teenager

and you with that face that doesn’t change.

You befriended my father

in order to get to me.

Poor Grandfather.

You were there

at his deathbed

waiting for the end.

An unforeseen mood

drifted around the furniture

the walls seemed more white.

And there was someone else,

you were signalling to him.

He closed Grandfather’s eyes

and paused for a moment to study me

I forbid you to return.

Every time I see you

my blood runs cold.

Stop persecuting me,

I beseech you.

I have loved another for years now

and your offerings don’t interest me.

Why do you always wait for me

in shop windows

in the mouth of sleep

under Sunday’s indecisive sky?

Your greeting is a locked room.

I saw you the other day with the children

I recognised the suit:

the same tweed as back then

when I was a student

and you were a friend of my father’s.

Your ridiculous lightweight suit.

Don’t come back,

I tell you again.

Don’t hang around any more

in my garden.

You will frighten the children

and the leaves will fall:

I have seen them.

What is this all about?

You are having a quick laugh

with that everlasting laughter

and you will keep on

trying to force a meeting with me.

The children,

my face,

the leaves,

all lost in your pupils.

Nothing will stop you winning.

I knew it at the start of my letter.

Translations from the Spanish by Richard Gwyn, first appeared in Poetry Wales, Vol. 46 No. 3 Winter 2010/11.

Drake in the South Sea

To schoolchildren of my generation, Sir Francis Drake was a hero, the epitome of English sangfroid, insisting on finishing his game of bowls before dealing with the Spanish Armada as it sailed up the Channel. It didn’t happen quite like that, of course, but who cares. The sea captains who forged the first imprint of Empire under Elizabeth the First have gone down here as great patriots, but are known to children in schools throughout Iberia and Latin America simply as pirates. In fact I remember looking through the history homework of my friend Nelson Pereira’s younger sister Elsa, while staying at their house outside Lisbon in 1983 and being shocked to see Drake being vilified in categorical terms. I imagine he doesn’t get much of a press in Irish school history books either, as he was involved in a massacre of 600 people during the English enforced plantation of Ulster in 1575. But that is how it goes: history is an imprecise art, dependent entirely on the perspective of the historian. Rather like fiction, in fact.

While in Argentina last month, I got into a lengthy discussion about the pirate Drake, and buccaneers of his ilk, on discovering that Drake entered the River Plate on his travels, and, I was told, sailed up the Paraná. I said to my companions that in Britain we did not speak of Drake as a pirate at all, not by any means, and that the first time I had heard him referred to in those terms was reading Gabriel Garcia Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude:

“When the pirate Sir Francis Drake attacked Riohacha in the sixteenth century, Úrsula Iguarán’s great-great-grandmother became so frightened with the ringing of alarm bells and the firing of cannons that she lost control of her nerves and sat down on a lighted stove. The burns changed her into a useless wife for the rest of her days. She could only sit on one side, cushioned by pillows, and something strange must have happened to her way of walking, for she never walked again in public. She gave up all kinds of social activity, obsessed with the notion that her body gave off a singed odor. Dawn would find her in the courtyard, for she did not dare fall asleep lest she dream of the English and their ferocious attack dogs as they came through the windows of her bedroom to submit her to shameful tortures with their red-hot irons.”

The BBC history entry on Drake gives the bare outlines:

Francis Drake was born in Tavistock, Devon in around 1540 and went to sea at an early age. In 1567, Drake made one of the first English slaving voyages as part of a fleet led by his cousin John Hawkins, bringing African slaves to work in the ‘New World’. All but two ships of the expedition were lost when attacked by a Spanish squadron. The Spanish became a lifelong enemy for Drake and they in turn considered him a pirate.

In 1570 and 1571, Drake made two profitable trading voyages to the West Indies. In 1572, he commanded two vessels in a marauding expedition against Spanish ports in the Caribbean. He saw the Pacific Ocean and captured the port of Nombre de Dios on the Isthmus of Panama. He returned to England with a cargo of Spanish treasure and a reputation as a brilliant privateer. In 1577, Drake was secretly commissioned by Elizabeth I to set off on an expedition against the Spanish colonies on the American Pacific coast. He sailed with five ships, but by the time he reached the Pacific Ocean in October 1578 only one was left, Drake’s flagship the Pelican, renamed the Golden Hind. To reach the Pacific, Drake became the first Englishman to navigate the Straits of Magellan.

He travelled up the west coast of South America, plundering Spanish ports. He continued north, hoping to find a route across to the Atlantic, and sailed further up the west coast of America than any European. Unable to find a passage, he turned south and then in July 1579, west across the Pacific. His travels took him to the Moluccas, Celebes, Java and then round the Cape of Good Hope. He arrived back in England in September 1580 with a rich cargo of spices and Spanish treasure and the distinction of being the first Englishman to circumnavigate the globe. Seven months later, Elizabeth knighted him aboard the Golden Hind, to the annoyance of the king of Spain.

In 1585, Drake sailed to the West Indies and the coast of Florida where he sacked and plundered Spanish cities. On his return voyage, he picked up the unsuccessful colonists of Roanoke Island off the coast of the Carolinas, which was the first English colony in the New World. In 1587, war with Spain was imminent and Drake entered the port of Cadiz and destroyed 30 of the ships the Spanish were assembling against the British. In 1588, he was a vice admiral in the fleet that defeated the Armada. Drake’s last expedition, with John Hawkins, was to the West Indies. The Spanish were prepared for him this time, and the venture was a disaster.

Drake died on 28 January 1596 of dysentery off the coast of Portobelo, Panama.

Apparently, before dying, he asked to be dressed in his full armour, which reminds me of the death by suicide of Captain Hans Langsdorff of the Graf Spee (see post of 22 September).

He was buried at sea in a lead coffin. Divers continue to search for the coffin.

Last year I was looking at some of the lesser-known historical poems of the great Nicaraguan poet Ernesto Cardenal (born 1925), Sandinista, theologian, rebel priest, and translator of Ezra Pound into Spanish. I was struck by the rather Poundian flavour of some of these, and particularly taken by the following poem, written in the voice of a Spanish sea captain and based on a true account, in which Drake comes across as quite an honourable fellow, in spite of his terrible reputation.

DRAKE IN THE SOUTH SEA

Realejo, 16th April 1579

For Rafael Heliodoro Valle

I set out from the port of Acapulco on the twenty-third of March

and steered a steady course until the fourth of April, a Saturday,

and half an hour before daybreak

we saw a ship draw alongside us

its sails and prow silver in the moonlight

and our helmsman shouted at them to make way

and they might as well have been sleeping, for they did not reply.

Another voice shouted over: FROM WHERE DOES YOUR SHIP SAIL?

and they answered, from Peru, and that it was the Miguel Angel

and then we heard trumpets and the firing of muskets

and they ordered me to board their boat

and I was taken to the Captain.

I found him pacing on the bridge

and I approached him and kissed his hands, and he said to me:

What gold or silver does your ship carry?

And I told him: None at all.

None, my lord, only my plates and cups.

After which he asked me if I knew the Viceroy,

and I told him that I did. And I asked the Captain

if he was truly Captain Drake,

and he said he was, the very same.

We stayed talking a long while, until it was time to eat

and he ordered me to sit at his side.

His plates and cups are silver, with golden borders,

adorned with his coat of arms.

He has many bottled perfumes and scented waters

which he says were given him by the Queen.

He always eats and drinks to the accompaniment of violins,

and takes with him painters who make pictures all along the coast.

He is a man of some twenty-four years, small, with a blonde beard,

He is a nephew of the pirate Juan Aquinas,

and he is one of the greatest sailors on the seas.

The following day, which was a Sunday, he dressed in great style,

And ordered his men to hoist banners

and pennants of many colours at the mastheads.

The bronze rings and chains and embellished handrails

and the lights of the quarterdeck

shone like gold.

The ship was a golden dragon among the dolphins.

And we went, with his page, to my ship, to see the coffers,

and he spent the whole day, until nightfall, inspecting my cargo.

What he took from me was not much,

a few baubles I owned,

and he gave me a cutlass and a small silver brazier for them

asking my forgiveness,

but that it was for his lady he had taken them,

and I was free to leave in the morning as soon as there was a breeze

and I thanked him for that,

and kissed his hands.

He carries in his galleon three thousand bars of silver

and three coffers filled with gold

and twelve great coffers of pieces of eight,

and he says they are heading for China

with navigation charts and a Chinese pilot they captured . . .

(Translation by Richard Gwyn, first published in Poetry Wales, Vol. 46 No. 3, Winter 2010/11)

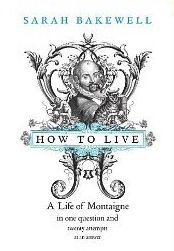

Montaigne and the acceptance of uncertainty

The essay, we are being told, is back. An editorial in The Guardian on 5 May celebrates the alleged event and announces a new specialist publisher, Notting Hill Editions, which has released a range of cloth-covered hardbacks, ranging from Samuel Rogers to Georges Perec. However, many of us never suspected that the essay had gone away. This discursive genre, in which the author is given space to explore a more or less impressionistic or apparently random cascade of ideas rather than provide a detached and critical analysis of a particular topic, has a considerable history, but can be traced – unlike any other literary genre – to a single individual, a minor French aristocrat of the sixteenth century named Michel de Montaigne (1533-92).

Sure, there had been comparable examples of introspective or speculative prose writing before him, notably by the Italian scholar and poet Petrarch (1307-74) and, at a stretch, Machiavelli (1469-1527), but Montaigne was the first modern essayist in two very particular ways. He was the first to apply the word ‘essai’ from the French verb ‘essayer’, and from which the English assay – meaning an ‘attempt’ – was a simple step; and his unique contribution to world literature was that he made himself the subject of his own work: he was the first to bring the spotlight onto himself as the topic of his writing, or, as Aldous Huxley put it in the preface to his own collected essays, to deliver ‘fragments of reflective autobiography’ and to ‘look at the world through the keyhole of anecdote and description’. Nearly five hundred years on, we find that the genre that Montaigne began, of self-reflexive prose in which the thoughts and actions of an individual constitute the subject matter and determine the direction of the writing, marks out a lineage that leads directly to the contemporary infatuation with autobiographical writing; the glut of misery memoirs, ‘sick lit’, confessional and celebrity memoirs with which the publishing industry is obsessed, not to mention the contemporary trends of blogging, social networking and twittering. By no means should Montaigne be blamed for these terrible things, but we might consider that in some important ways he started it all.

Montaigne has thus become extremely interesting to publishers, and the two books I have before me reflect the wide appeal that this Renaissance gentleman has to a twenty-first century readership. Both books have long and unwieldy titles. But Sarah Bakewell’s How to Live: a life of Montaigne in one question and twenty attempts at an answer is very good indeed, while Saul Frampton’s When I am playing with my cat, how do I know she is not playing with me: Montaigne and being in touch with life, although not without virtues, is filled with unfortunate and confusing turns of phrase, as well as numerous errors of editing and proofreading, and falls far behind Bakewell in both content and prose style.

Montaigne has had a long and interesting relationship with posterity. While his works brought him instant fame in sixteenth-century France, and were translated into English shortly after the author’s death, he fell foul of the Catholic church on account of his libertarian attitudes and relaxed morality, upsetting major French philosophers of the seventeenth century such as Pascal and Descartes. His work was placed on the Catholic Church’s Index of Prohibited Books in 1676, remaining banned for nearly two hundred years. Although the French libertins adopted him and he was praised by Voltaire (and plagiarised by Rousseau), it was not until Nietzsche that Montaigne found a true descendant, one who called him ‘this freest and mightiest of souls’ and who would write: ‘That such a man wrote has truly augmented the joy of living on this earth.’ Montaigne lived, says Bakewell, as Nietzsche would have liked to live, questioning everything and yet managing  to live his own life in a way that held no regrets – ‘If I had to live over again, I would live as I have lived’ is a favourite and enviable quotation. Everything, says Bakewell, that ‘most repelled Pascal about Montaigne – his bottomless doubt, his ‘sceptical ease’, his poise, his readiness to accept imperfection’ were precisely those things that appealed to Nietzsche and which impress Montaigne’s fans today. At the man’s centre lay a pervasive scepticism, allied to a warm and humane engagement with the day-to-day; a hatred of cruelty; a profound but unsentimental love of nature and of animals, and an irrepressible curiosity about other societies and their customs. Montaigne is also known as an epicurean and a stoic in the mould of Marcus Aurelius (to which, as both authors point out, he adhered less stringently as the years went by).

to live his own life in a way that held no regrets – ‘If I had to live over again, I would live as I have lived’ is a favourite and enviable quotation. Everything, says Bakewell, that ‘most repelled Pascal about Montaigne – his bottomless doubt, his ‘sceptical ease’, his poise, his readiness to accept imperfection’ were precisely those things that appealed to Nietzsche and which impress Montaigne’s fans today. At the man’s centre lay a pervasive scepticism, allied to a warm and humane engagement with the day-to-day; a hatred of cruelty; a profound but unsentimental love of nature and of animals, and an irrepressible curiosity about other societies and their customs. Montaigne is also known as an epicurean and a stoic in the mould of Marcus Aurelius (to which, as both authors point out, he adhered less stringently as the years went by).

His brand of philosophy – preferring to offer details wrapped in anecdote rather than expounding abstractedly – has a distinctly un-French edge to it that has always been popular in Britain, and his fan base ranges from Thomas Browne to Virginia Woolf, who admired him above all for his insistence on perpetually observing his immediate environment, his emotions and his interactions with the world.

The influence that Montaigne may or may not have had on Shakespeare has generated a considerable amount of speculative scholarship, based largely on a speech of Gonzalo’s in Act Two of The Tempest, which repeats, almost verbatim, an extract from Montaigne’s essay ‘On Cannibals’. Shakespeare almost certainly knew John Florio, Montaigne’s English translator, and Montaigne’s influence has not only been discerned on the soliloquies of Hamlet – which would suggest that Shakespeare had sight of Florio’s translation before publication – but with greater assurance in the general tendency of Shakespeare’s later work towards a reflexive mode centred on the ever-questioning interlocutor. The uncertain or bewildered protagonist, suffering (or flaunting) a surfeit of experiential anxiety, was an entirely new phenomenon in literature, and according to Bakewell locates Montaigne and Shakespeare as ‘the first truly modern writers, capturing that distinctive modern sense of being unsure where you belong, who you are, and what you are expected to do.’

A further similarity between Montaigne and Shakespeare is what the critic Jonathan Dollimore has called ‘a form of self-consciousness which implies simultaneous awareness of experience and the experiencing self’ as well as in the kind of relativism, according to Richard Wilson, which arises in both writers ‘from their sensation of the contingency of beliefs’. This is encapsulated, in both men’s work, in their interiority. In Montaigne, it takes a pronounced, monological turn at times:

I turn my gaze inward. I fix it there and keep it busy. Everyone looks in front of him; as for me, I look inside of me; I have no business but with myself; I continually observe myself. I take stock of myself, I taste myself… I roll about in myself.

And yet this is not solipsism – the state in which only the self exists or can be know – but something closer to Hamlet’s self-observation in the famous soliloquies. The image of Montaigne ‘rolling about in himself’ is nicely a propos, especially given his fondness for dogs (and indeed his love of animals of all kinds). Montaigne famously refers to his cat in one of his essays (and in the title of Frampton’s book), but his weakness in giving in to his dog’s playfulness earned him Pascal’s disdain:

I am not afraid to admit that my nature is so tender, so childish, that I cannot well refuse my dog the play he offers me or asks of me outside the proper time.

Montaigne also displays an unusually compassionate rapport with others – an identification with otherness that extends not only to the Protestant ‘enemy’ within sixteenth-century France (for which he was rebuked and mistrusted by fellow-Catholics during the long period of civil conflict through which he lived) but also to other human tribes. He was struck by the beliefs of the Brazilian Indians whom he encountered at the king’s court in Rouen, who ‘spoke of men as halves of one another, wondering at the sight of rich Frenchmen gorging themselves while their ‘other halves’ starved on their doorstep.’ Furthermore, beyond his interest in cats and dogs, there is an almost pagan feel for, or identification with the natural world and animal life, something which provides Bakewell with one of her most interesting asides. While discussing Montaigne’s influence on Virginia Woolf, and both writers’ insistence on ‘paying attention’ in a way that eschews habitual modes of perception and categorisation, she cites Woolf’s diary of 1919:

I remember lying on the side of a hollow, waiting for L[eonard] to come & mushroom, & seeing a red hare loping up the side & thinking suddenly ‘This is Earth Life.’ I seemed to see how earthy it all was, & I myself an evolved kind of hare; as if a moon-visitor saw me.

Bakewell observes that this ‘eerie, almost hallucinatory moment’ enabled Woolf to see herself as part of a continuum, as essentially nature-bound – this is Earth Life – in a way that would not be remotely possible to an observer whose eyes were ‘dulled by habit’. The overcoming of habitual responses lies at the heart of Montaigne’s challenge. ‘Habit’ according to Samuel Beckett, ‘is the ballast that chains the dog to his vomit’: and it is precisely what Montaigne seeks to uncover and dismantle in his essays. He does this in various ways, but one of his favourites is to run through apparently marvellous and diverse customs from distant cultures in order to convince his readers that what they take for granted is only a matter of what they are accustomed to. As he himself put it: ‘Everyone calls barbarity what he is not accustomed to.’ His essay ‘Of Custom’ discusses, by turn, the question of whether or not one should blow one’s nose into one’s hand or into a piece of linen; how in a certain country no one apart from his wife and children may speak to the king except through a special tube; how in another land ‘virgins openly show their pudenda’ while ‘married women carefully cover and conceal them’; how in other (unspecified) locations the inhabitants ‘not only wear rings on the nose, lips, cheeks and toes, but also have very heavy gold rods thrust through their breasts and buttocks’; how in some nations ‘they cook the body of the deceased and then crush it until a sort of pulp is formed, which they mix with wine, and drink it’; where it is a desirable end to be eaten by dogs; where ‘each man makes a god of what he likes’; where flesh is eaten raw; where they live on human flesh; where people greet each other by putting their finger to the ground and then raising it to heaven; where the women piss standing up and the men squatting; where children are nursed until their twelfth year; where they kill lice with their teeth like monkeys; where they grow hair on one side of their body and shave the other. By blasting his reader with these numerous examples of apparent strangeness, Montaigne makes them question the practices which they habitually regard as unquestionable and normal in a new light. Indeed, he raises many of the issues that cultural anthropology began to tackle four centuries later, and he can safely be regarded as an early relativist. When he had the opportunity to speak with some American Indians from Brazil, the Tupinambá tribe, of which a delegation was brought before the court at Rouen, he was not simply concerned with ‘observing’ them, as though they were rare specimens of primordial life: he was much more interested in recording their amazement at their French hosts. ‘Watching them watch the French’ says Bakewell, ‘was an awakening, like Virginia Woolf’s on the hillside’.

Bakewell’s interpolation of the life story with aperçus of the kind with Woolf, and elsewhere with Nietzsche, adds considerably to the weave and texture of her account. I finished her book feeling as though I had thoroughly shared in a deeper understanding of Montaigne’s work. Hers is a rare achievement. It is a shame then that I cannot similarly compliment Frampton’s book. An example of their distinct approach to subject matter might be illustrative.

All commentators are agreed that Montaigne’s awakening as a writer came about through his friendship with a colleague and fellow counsellor in the Bordeaux parliament, Etienne de La Boétie. The two men were inseparable friends for four years, and then La Boétie died. Montaigne’s grief was intense and long-lasting, and he would write of their friendship: ‘If pressed to say why I loved him, I feel that it cannot be expressed, except by saying: because it was him; because it was me.’ The line is a unique and moving testimony to friendship. But while Bakewell is content to regard La Boétie as Montaigne’s ‘literary guardian angel’, looking over his shoulder during the composition of the essays, Frampton tediously – and without any evidence – insists on the possibility of a sexual relationship between the men. Not that it matters, of course: but really, why should we care? Why can’t we simply accept that this is at least a possibility, rather than having to indulge this prurient and weary conjecture that amounts to little more than anachronistic gossip-mongering?

But this, alas, is only one of Frampton’s failings: on page 29 we learn that the town of Agen is to the south-west of Bordeaux (placing it firmly in the Bay of Biscay), but on the next page it has moved (correctly) to the south-east of Bordeaux; on page 33 a painting is being described in which ‘One of [the men] is dressed as a Roman solder (sic), the other wearing the gown of a dying man.’ What, one wonders, is ‘the gown of a dying man?’ Must one know that one is dying before wearing such a garment? Or does the wearing of such a gown somehow condemn one? And there is more: discussing how plague ravaged the countryside in the 1580s, we are suddenly and randomly informed about an alleged event that took place at the opposite end of France: ‘At Ales near Lille in 1580, a young man called Jehan le Porcq died of a contagious illness, spending his final days in a shed at the bottom of his father’s garden.’ And on page 83 we learn that ‘a fog descended over northern Europe… It covered the Rhine… scaled the high walls of Oxford and surrounded Aristotle.’ There is far too much of this kind of nonsense. Moreover, the text is littered with failures of meaning, failure of tense agreement, errors of punctuation, and missing words. Frampton must take a large chunk of the blame, but surely Faber and Faber employ editors and proofreaders?

We should therefore be doubly grateful that Bakewell’s book provides an articulate and sympathetic introduction to the man and his work; but for anyone seriously wishing to make the acquaintance of a writer renowned for his self questioning rebuke ‘What do I know?’ – pre-empting postmodernity’s chronic self-doubt, but with a leavening of subtle humour, even at times hilarity – the Essays are a delight in store.

This post first appeared as a review article in the latest issue of New Welsh Review, a magazine full of good and interesting things. In fact why not subscribe here.

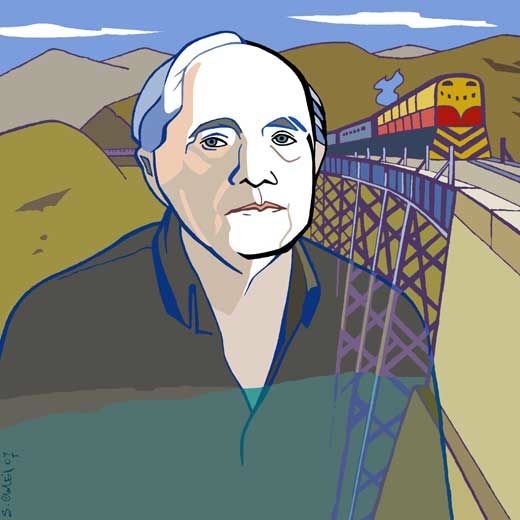

J.M. Coetzee in Buenos Aires

Coetzee came to Buenos Aires to deliver the final reading of the festival last night. I am not really authorized to write at length about Coetzee, having only read two of his novels, which I found admirable, and a collection of his essays. However, I will certainly read more of his work now, and am particularly keen to read his own account of his life, of which there are now three volumes.

There were, of course, the introductions in Spanish: the first brief, the second rather long, both of them adulatory, then Coetzee emerged from the wings like a tall and elegant rock star (think a slightly more reverend Clapton with a tie). I was sitting in the front row, and had been approached by a security guard who told me that the first two rows were reserved for guests of the funding organisation. I told him I was an invited guest of the festival and stayed in my seat. He moved off, unsure what to do about me. Half the seats in the front two rows then remained empty, even though there were dozens of people outside who had been refused tickets, and others sitting on the steps in the foyer watching the proceedings on a big screen and possibly hundreds who had been told the event was sold out. The photographers had clearly been instructed that they could snap away only during Coetzee’s introduction, and not in the reading proper. In any case, I was able to take a few pictures of my own, and they came out rather well.

Coetzee made a brief introductory statement in faltering Spanish, and then he read a story, set in a house in Spain (perhaps he chose one with an Hispanic theme for the occasion, believing there is not a lot of difference between one Spanish speaking country and the next, one with a few Spanish words in, like ‘vaya con dios’, which no one ever says unless they’re about a hundred years old). The story lasted half an hour, or forty minutes, I’m not sure, I think I drifted off briefly, and it was about a man called John (which is Coetzee’s name) visiting his mother, who lives in a village in Castille, and keeps a lot of cats and the village flasher (yes, that’s right, she has made her home available to the village pervert, because he was going to be taken away by social services and she stepped in and said she would look after him. I’m not sure this is how things work in Spain, but I guess we can let that go in the name of poetic licence). The story was okay, but did he need to fly thousands of miles to read it? Because that was all he did: read a story, then sit down and sign books for his abundant fans, who queued patiently (a very difficult task for Argentinians, or at least for Porteños) who came onto the stage one at a time, were allowed to exchange a few brief words with the great man, then trundled off clutching their books like they were holy relics. I wonder how much he got paid to do this. I wonder if he is doing any sightseeing while he is here. He certainly won’t be tasting the wonderful Argentinian steaks as he is a vegetarian; nor can I imagine is here much of a drinker, so will not be tasting the fine Argentinian wines. Coetzee is however a rugby fan, and since the world cup is on, the festival president tells me, he was able to talk to him about rugby on the drive back from the airport. If it had been me I would have expressed my opinion that his team (assuming he still supports the Springboks and not the Wallabies, after adopting Australian nationality) was extremely lucky to get away with a one-point victory over my team last week, but of course that is done and dusted now and we must press on. At least the world cup curse of Samoa has now been lifted, and if things go well against Fiji and Namibia we will most likely meet the Irish in the quarter-finals, which is do-able.

Coetzee stands in a very upright manner. There is, in fact, something quintessentially upright about him. Someone who know him expressed the view to me that this is related to a self-abnegating Afrikaaner protestant streak (although he did attend a Catholic school, so presumably got the worst of both worlds). This is not a man who will let his scant hair down. According to a reliable source (i.e quoted on Wikipedia) he lives the life of a recluse, and “a colleague who has worked with him for more than a decade claims to have seen him laugh just once. An acquaintance has attended several dinner parties where Coetzee has uttered not a single word.” In fact he is so reclusive that the Flash player did not want to upload my photo of him, so I am using a picture provided by Flickr instead. In the Wikipedia picture (which also refused to upload) he is wearing the same tie as last night, or appears to be, unless of course he has several editions of the same tie. The Wikipedia entry also informs me he has expressed support for the animal rights movement. Because he rarely gives interviews and so forth, signed copies of his books are highly valued.

Despite his saying that he was pleased to be here, he did not really give the impression of being overjoyed about the occasion. He was more like a pontiff bestowing a blessing on his devotees, with great dignity and reserve. And the ridiculous notion occurs to me that there are two Coetzees, one of them here in Buenos Aires, reading his story like a monk reading from the sacred text to his silent admirers, the other scribbling away, locked in his cell wherever it is he lives, Adelaide or thereabouts. The one I saw last night is the phantom Coetzee, the one that the real Coetzee very occasionally sends out to commune with his public, a doppelganger Coetzee who is dressed like a banker, reluctantly engaged in the contemporary phenomenon of the Book Signing, that strange ritual in which members of the reading public are able to pretend that they have a personal relationship with the author, and walk away clutching their books tight to their chests as though some of his greatness were now trapped in the trail of ink on the title page, that they have absorbed some of the fallout of his ascetic majesty, and will now, through some mystical process not unlike transubstantiation, be the richer for it.

The last hundred days

Within weeks of publication Patrick McGuinness’s debut novel, The Last Hundred Days found itself on the Man Booker long list, and deservedly so, although it failed to make the shortlist on the 5th September. Whatever. Set in Bucharest, the novel reawakens in the reader that state of stunned disbelief in the autumn of 1989 as successive Soviet bloc countries underwent bloodless revolutions, until there was only Romania there at the end of the queue, making a bloody hash of it. The novel describes the despicable oppression and deprivation of the Romanian people in the build-up to that coup, and paints a sordid picture of the corruption and hypocrisy of their rulers.

Within weeks of publication Patrick McGuinness’s debut novel, The Last Hundred Days found itself on the Man Booker long list, and deservedly so, although it failed to make the shortlist on the 5th September. Whatever. Set in Bucharest, the novel reawakens in the reader that state of stunned disbelief in the autumn of 1989 as successive Soviet bloc countries underwent bloodless revolutions, until there was only Romania there at the end of the queue, making a bloody hash of it. The novel describes the despicable oppression and deprivation of the Romanian people in the build-up to that coup, and paints a sordid picture of the corruption and hypocrisy of their rulers.

At the same time it feels oddly contemporary, especially in the way that a grasping elite escape the consequences of their actions and rise above the chaos that they perpetrate. Not that the Ceausescu’s themselves did, of course, their messy trial and execution can still be viewed on youtube, and it provides a resonant coda to the reading of this novel.

The opening chapter is superb, its discourse on the state of boredom offering a kind of conceptual counterpoint to the unfurling narrative, with its cast of impressively drawn characters, that is almost Tolstoyan in scope: “In the West we’ve always thought of boredom as slack time, life’s lift music sliding off the ear. Totalitarian boredom is different. It’s a state of expectation already heavy with its own disappointment, the event and its anticipation braided together in a continuous loop of tension and anti-climax.” McGuinness is an accomplished poet and writes with superb clarity. The novel is littered with aperçus of a brilliance that has the reader reaching for a pencil. Here is Bucharest: “a heat-beaten brutalist maze whose walls and towers melted like sugar, and where the roots of trees erupted through the pavements.” And here is the unctuous consular attaché Wintersmith (straight out of Greene-land) and the British expat community, “where largely identical people fuck each other interchangeably”; here is the Boulevard of Socialist Victory: “a vast avenue that didn’t so much vanish into the distance as use it up, drawing everything around into itself.” And here is the grim Stoicu, interior minister and Ceausescu sidekick, with the “eyes of a man who sought in those around him the lowest motivation and always found it.”

I was fascinated to learn that Ceausescu was so paranoid that he would duplicate, no, triplicate his daily motorcade through Bucharest with simultaneous decoy performances in other parts of the city: “sirens, cars, Ceausescu’s motorcade – the real one and its decoys hurtling through Europe’s saddest dictatorship. One of the cars was for the Ceausescu’s dog, and he even had two doggy decoys, a punchline to a joke no one could any longer bear to tell about a world whose brutality was matched only by its absurdity.”

McGuinness was himself in Bucharest just prior to the fall of the regime, and his observations appear to have the scent of authenticity. This is a novel that rages and flows by turn, but rarely disappoints, tugging caustically towards its inevitable denouement.

A version of this review appeared in The Independent on 8 September 2011.

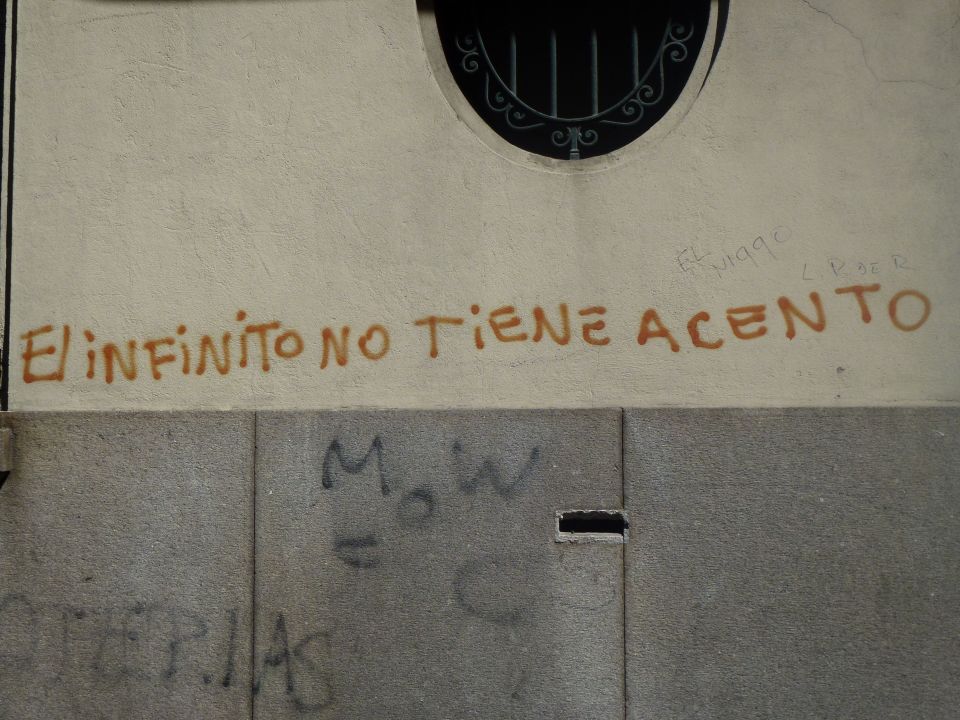

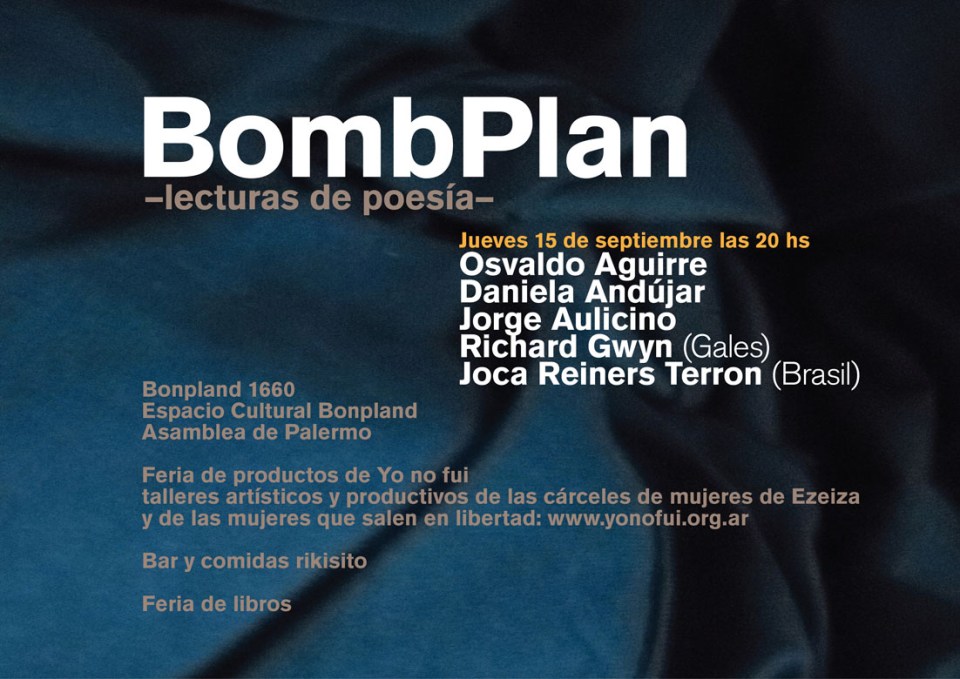

It’s always an education to read in unusual locations. The organizers of FILBA appear to be steering me towards a socially engaged role that I am not normally associated with back in the UK. But that’s fine with me. The reading last night took place in a cobbled courtyard next to a rehabilitation centre for women recently released from jail, and behind an abandoned market, a steel-girdered hangar that resembles a nineteenth century railway station. Outside, the place was covered in graffiti and creeping vines, and in the darkness a wind began to stir, causing a few paper cups to scuttle across the cobbles like the rats that you knew were there, but were sitting out the poetry reading in a nearby drain. The perennial smell of the Buenos Aires night – barbecued meat, with an overlay of almonds – wafted by, and an engaged and enthusiastic audience sat alongside the vendors of bags, table-cloths and other artefacts made by the women prisoners.

I am posting a poem that I read last night, as well as at the Club de Traductores on Monday, because it seems to be popular here – probably due to the excellence of the translation – but which I don’t think I have ever performed back home. My Spanish reader on this occasion was the poet and journalist Jorge Aulicino. Strange how on a reading tour there is usually one piece that gets more attention than the others, for no particular reason. It is followed by the Spanish translation by Jorge Fondebrider, since Blanco’s blog has acquired an encouraging following in Argentina and Spain, perhaps because they think I am someone I am not.

Dissolving

When you spoke of dissolving in my arms

I realised it was not a figure of speech

that in a sense (in any sense), you meant it

to be just so, that you would disintegrate in me,

I in you, and both of us in water. Could this be

what is meant by marriage, in which both parties

disappear entirely, leaving only ripples

on the water’s quiet surface? But marriage

was a curious fantasy for us, and who could

possibly officiate? You were promised to another,

a dark figure stalking alleyways at night,

an ever-busy debt-collector, and I knew

my thin credentials would never count for much

with your imaginary father. So I led you

to a pond instead, with lilies and an oriental bridge,

a bench named for a local shopkeeper,

the path which circumscribed the water

shaded by hydrangeas and a vast magnolia.

The place was known to me, but since

the I that remembered things was by now

already dissolving in the you that forgot things,

the memory might well have been a false one.

You walked around the pond, around my island,

diminished with each circuit, each time drawn by

the gravity of the island’s green intelligence,

around and around, while I waited, an idiot

in a drama with no plot, no foreseeable conclusion.

from Being in Water by Richard Gwyn, with drawings by Lluís Peñaranda

Disolverse

Cuando hablaste de disolverte en mis brazos

advertí que no era una figura retórica,

que en un sentido (en todo sentido), lo decías en serio

que así fuera, desintegrarte en mí,

yo en ti, y ambos en agua. ¿Será eso

lo que se llama matrimonio, cuando ambas partes

desaparecen completamente, dejando apenas ondas

sobre la quieta superficie del agua? Pero para nosotros

el matrimonio era una curiosa fantasía, ¿y quién quizás

podría celebrarlo? A otro estabas prometida,

una figura oscura que acechaba de noche en callejones,

un cobrador de deudas siempre ocupado, y yo sabía

que mis escasas credenciales jamás servirían de mucho

con tu padre imaginario. Así que en cambio te conduje

a un estanque, con lirios y un puente oriental,

un banco bautizado con el nombre de un comerciante local,

el camino que circunscribía el agua

sombreado por hortensias y una vasta magnolia.

El lugar me resultaba conocido, pero desde que el yo

que recordaba cosas para entonces ya estaba

disolviéndose en el tú que se olvidaba cosas,

el recuerdo bien podría haber sido falso.

Caminaste alrededor del estanque, alrededor de mi isla,

disminuida con cada vuelta, cada vez atraída

por la gravedad de la inteligencia verde de la isla,

una y otra vez, mientras yo esperaba, un idiota

en un drama sin argumento, sin previsible conclusión.

_

Villa Ocampo

Victoria Ocampo was one of the great patrons of the arts of the first half of the twentieth century. She first published Borges in her magazine Sur and she hosted and promoted writers and artists from around the world on their visits to South America. Among others Igor Stravinsky, Aldous Huxley, Albert Camus, André Malraux, Indira Gandhi, Drieu La Rochelle, Antoine de Saint Exupéry, Rabindranath Tagore, Albert Camus and Graham Greene were guests at the Villa Ocampo, and Lorca’s Romancero Gitano was published by her.

Yesterday, along with Cees Nooteboom and his wife Simone, Minae Mizumura, and the Argentinian novelist Inés Garland (who kindly drove us there), I was a guest at the Villa Ocampo. We had lunch, and then received a guide from the house manager, the exteremely well-informed Nicolás Helft, who presented me with a 1961 issue of Sur that contains the Spanish translation of a short story by Nabokov ‘Scenes from the life of a double monster’ (which appears, in English, in Nabokov’s Dozen) as well as poems by Gregory Corso and Lawrence Ferlinghetti.

The house itself is spectacularly lovely, even if the interior veers towards the state of a mausoleum, with rooms kept intact from the era in which they enjoyed their greatest glory. The grounds, filled with great trees and green lawns, once spread down to the River Plate, several blocks away, but is now considerably smaller (though still ample). The odour of privilege wafts around the corridors and up the stairwells. I would not have liked to have got the wrong side of Victoria (and those who crossed her often lived to regret it). So I sat in her chair and meditated on the state of being Victoria Ocampo for a minute or two, and for a brief moment felt the thrill of something like victory. This was quite alarming, although not unpleasant.

For those who understand Spanish, here is a link that connects to Jorge Fondebrider’s website Club de Traductores de Buenos Aires and a video of my interview and reading from Monday evening.

Good things about being Welsh: No. 3

We are so kind and noble we allow other teams to beat us at our national sport. I am not absolutely certain this is an asset, but it indicates true strength of character and I am sure the Japanese have a word for this kind of motiveless self-sacrifice.

We are so kind and noble we allow other teams to beat us at our national sport. I am not absolutely certain this is an asset, but it indicates true strength of character and I am sure the Japanese have a word for this kind of motiveless self-sacrifice.

In today’s Rugby match against South Africa (which I watched at 5.30 a.m. local time despite only returning to my hotel at 2.oo following a reception at the Dutch Embassy in honour of the novelist Cees Nooteboom), the Welsh team played with a conviction and courage that was barely recognizable, and they probably deserved to win, whatever that means. (It means nothing in sport actually, which is the whole point). Ych a fi.

On another note, I was chatting with the Dutch ambassador’s wife last night (I really wanted to use that line, please forgive me) and it seems the British Ambassador is a Welsh woman.That must surely count for something, honouring the bardic tradition etc. However nothing at all has been set up at the fabulously impressive British Embassy to celebrate Blanco’s arrival in Buenos Aires, which Blanco feels is rather remiss.

But then Cees Nooteboom is famous (as well as seeming a very nice man) and Blanco is not. Apparently when Hanif Kureishi came over they gave him a proper bean feast. Blanco is clearly not important enough. I am not sure how I feel about this, but probably it doesn’t compare with what our national Rugby team will be feeling today

Joaquín O. Giannuzzi

Having written about illness in various media over recent years – principally as a so-called academic and the writer of a memoir, The Vagabond’s Breakfast, I am alert to the ways that other writers approach the subject, and am usually interested in what they have to say (so long as their writing does not launch into tedious new-age rage at the incompetence of ‘Western’ medicine, or degrade itself by spurious claims to the kind of quackery familiar to devotees of certain ‘wellness’ manuals).

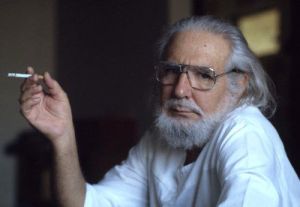

I have recently been translating the poetry of the Argentinian Joaquín O. Giannuzzi, whose work is sadly neglected in the English-speaking world, and discover that illness – while by no means a limitation – is a recurring theme in his poems. This is something that is hard to do without falling prey to over-familiar tropes and accusations of self-pity. He approaches the topic as he approaches all his subject matter, with a lugubrious humour, with pathos, and with painful accuracy. I am posting three of his poems to mark my departure for his homeland later today. The original Spanish (which I have not reproduced here) is from the Poesía Completa, edited by Jorge Fondebrider, and published by Sibilina (Seville).

For Some Reason

I bought coffee, cigarettes, matches.

I smoked, I drank

and faithful to my personal rhetoric

put my feet on the table.

Fifty years old with the certainty of the damned.

Like almost everyone I messed up

without making too much noise;

yawning at nightfall I muttered my disappointment,

and spat on my shadow before going to bed.

This was all the response that I could offer to a world

that claimed from me a character that possibly

didn’t suit me.

Or maybe something else is at stake. Perhaps

there was a different plan for me

in some potential lottery

and my number was lost.

Perhaps no one settles on a strictly private destiny.

Perhaps the tide of history settles it for one and all.

This much remains to me:

a fragment of life that tired me out in advance,

a poem paralyzed halfway towards

an unknown resolution;

dregs of coffee in the cup

that for some reason

I never dared drain to the last drop.

On the Other Side

Someone has died on the other side of the wall.

At intervals there is a voice, hemmed in by sobbing.

I am the nearest neighbour and I feel

slightly responsible: blame

always finds an outlet.

In the rest of the building

no one seems to have noticed. They talk,

they laugh, they switch on televisions, they devour

every last scrap of meat and every song. If they knew

what had happened so close by, the thought

of death wouldn’t be sufficient

to alter the cardiac rhythm of the

building’s occupants.

They would push the deceased into the future

and their indifference would have its logic:

after all, no one dies any more than anyone else.

Intensive Care

In the bed opposite

the man woke up snoring

his open mouth set

in desperate conviction.

The serum was dripping

into his veins. From my belly

sprouted two plastic tubes

in which a pink foam bubbled

as if it were the definitive language

of my entrails. To one side

someone coughed up

the last of his viscera.

A springtime branch swayed

behind the window’s glass

flaunting the life owed us

in exchange for the disorders

that laid waste to our pale bones.

Everything seemed suspended

between universal infirmity

and the opportunities offered to death.

In the corridor a nurse fluttered by

and we followed her with eyes intent on

laying bare the fermented secret

of our clinical notes:

but we didn’t manage to reach

her distant and weary heart.

More thoughts on translation

I began translating, in a very amateur sort of way, when I first discovered the poetry of the Greek poet Yannis Ritsos at the beginning of the 1980s. Not only was my Greek inadequate to the task and I lacked any kind of self-discipline, but I was up against the superb existing translations of Edmund Keeley. I became easily disheartened by my feeble efforts and never stuck with it. It was much more fun to decode the English on restaurant menus, as many a traveller to Greece has discovered. Among the culinary delights I have encountered, both seen and unseen, are:

Giant Beams

The Baked Thing

Greek with cheese

Bowel stuffed with spleen

Bait smooth hound

Mixed Peasant

and

Custard of the Aunt.

All of these items of food have suffered the indignity of an over-literal translation by a scribe with faulty understanding of the target language (English), and while their entertainment value might be high, you are never sure what it is you are likely to be eating, unless of course you can read the Greek.

Some years later, I started a translation of Jean Giono’s novel Les Grands Chemins (which as far as I know has still not appeared in English) but was put off both by my frail grasp of French grammar and by the quantities of argot and slang. As with most of my endeavours at that period of my life, I had an unrealistic grasp of my own abilities.

However, I am nothing if not persistent, and having tried Greek and French and been found wanting, like a serial re-offender I thought I should try my hand at Spanish. When I had acquired enough of the language to read poetry without constant referral to the dictionary, I set about translating (or should I say despoiling) Antonio Machado – a bad choice, not only because he had been a challenge to far better translators than myself, but because his Spanish is, well, utterly embedded in the thought and landscape of Spanish – and I did not really appreciate or understand this at the time and thought that I was just not very good at translating poetry. However Machado really is more untranslatable than most, and perhaps this is the reason Don Paterson opted to go for much looser versions or interpretation in his collection The Eyes.

But with another Spanish poet, Jaime Gil de Biedma, I felt my translations begin to ‘work’ and moreover I could

sense an affinity with this writer that extended beyond the act of translation. There were English translations of his poems available but they seemed weak to me, and I wanted to make something better, do justice to his work in a way that his American translator had not: such is the arrogance of the beginner. So I worked on a few, sent them to a magazine, and they were accepted.

Later I was asked by the editor of the same magazine to work on skeleton or ‘crib’ versions of poems from Lithuanian and Slovakian, and make English poems of them. I agreed to do it, but it seemed a very risky affair, and nothing much to do with translation, more like playing darts with the lights off. I didn’t much enjoy the experience, but I have since taken part in workshops, working with poets who write in a language I do not speak, and if their English is good enough, it is possible to hammer out a good poem using an intermediary version – this is what the organization Literature across Frontiers manages to such good effect: in addition practitioners use a ‘bridge’ language, so that poets who speak distinct languages but share a third language in common (English, German, Spanish) can combine forces with a native speaker of the bridge language to make new versions of their work. It sounds complicated but it can be a very rewarding (as well as a tiring) process, and it must be said that a lot depends on the individuals gathered together on these occasions, and whether or not they happen to gel as a team.

But the kind of work done by Literature across Frontiers is at a far remove from the sort of translation done by individuals who work directly from a language which they know well into a language in which they are fluent, which is the daily round of the professional translator. I do not claim to be any such animal, but three years ago I became so interested in the act of translation that I put myself through the ordeal of preparing for and sitting the Institute of Linguists’ Diploma in Translation, the gold standard qualification for translators in the UK, and one with an astonishingly high failure rate (which I suppose keeps the Institute’s coffers topped up). I passed, so am now legitimately able to call myself a translator, although like nearly all the achievements I have realised over the years, all the hurdles I have overcome, there is always a sheen of scepticism about my own status, and I never quite manage to believe that the person with all the qualifications (and the nice suit and the office), the one called ‘Dr Blanco’, is actually me, but rather, he is an illusion.

What I am trying to say is that, like many people who do not admit it publicly, I think of myself as an impostor, a person impersonator, for many hours of the working day, and for this reason, ‘translator’ seems a very appropriate occupation. And why is this? Is there an association with the trickster, the coyote figure, or the dissembler? I think – and hope that I am not alone in thinking this – that there is something intrinsically fraudulent in the act of translation. You are trying to pretend that something is what it is not. So the trick is to make it sound as though it were not something that it is not, otherwise you end up writing translator-speak, with which we are all familiar from the study of Greek menus and garden furniture assembly kits.

The idea of translating into English is to make the words sound as though they were composed in English, which of course they were not, in the first instance. So we pretend, and share the pretence. If the translation is any good then we forget we are pretending. Simples.

But more than that, there is the profound satisfaction for the translator – something akin to the breaking of a code or the unravelling of a puzzle – when the correct phrase or expression slots into place, which makes translation, when it is going well, such a rewarding occupation. In Tim Parks’ absorbing essay ‘Prajapati’ (to be found in the collection Adultery and Other Diversions) he describes the pleasures and torments of translating Roberto Calasso’s Ka, on a very hot day. And at one point, as he kicks off his sandals to feel the cool of the tiled floor, he begins to spin off into the kind of meandering meditation that the act of writing often incites:

“I realise I am fascinated by models of the mind. By consciousness and representations of consciousness. Prajpati’s, Mahidasa Aitareya’s, Calasso’s, they are all hugely different minds from each other and from mine. I was never convinced by Leopold Bloom. And I sense that translation has something to do with this, this constant attempt to grasp difference, to overcome it, if only for a few moments, if only in the slippery surface of a text, to appropriate, but also to expand, to be there in Calasso’s study, understanding Calasso understanding Mahidasa Aitareya understanding the Rg Veda understanding Prajpati. Did they all find flies as irritating as I do?”

Norman di Giovanni, in his essay ‘A Translator’s Guide’ quotes Borges as saying “The translator is a very close reader; there is not much difference between translating and reading.” Di Giovanni finds this simple, clear approach to be in stark contrast to much of the talk, and theorizing about translation, which takes place, he says, on a “dizzyingly rarefied plane.”

The most helpful advice I have read on the craft of translation always keeps it simple, like Borges’ thing about being a close reader: understand the source text (decode it) and put it into language as clearly as possible (encode it). Working from these simplest of principles, and with the minimum of self-deception, are the kinds of rules even an inveterate self-doubter should find easy enough to follow.

And yet there is more, there is a twinge of excitement, almost a sense of vertigo, closely related to the type of exhilaration experienced when one’s own writing is going well (it is practically the same thing after all) which makes translation such a worthwhile occupation. Tim Parks finds this grappling with meaning to be like a constant exchange between the inchoate and the specific, between the undefined and the defined:

“Translation too is this, leaving the definition, the apparent definition, of the original, going through a state of indefinition, perhaps more original, in the Prajpati sense, than the original, where ideas are somehow held wordless, or almost, in my mind (I wish I could decide whether those ideas actually do become wordless) thence to reappear, gradually recompose themselves, from fuzz to clarity, or almost, in my own language.”

So much is contained by that ‘or almost’. Returning to Borges and simplicity, returning to the idea of an approximation. Perhaps that is the crux of all translation: it is an expression of the almost.

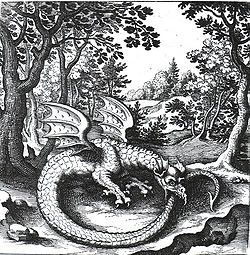

Into the Mystic

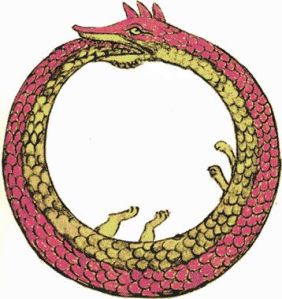

The motif of the ouroboros appears in the ancient cultures of Egypt, India, Greece and Mexico, and was of particular interest to European alchemists in the early modern era. Conventionally it depicts a serpent or a dragon eating its own tail, from the Greek oura/voros = tail-eater. To the alchemists the symbol came to signify cyclicity, and thus, in a human context, self-reflexivity. In my beginning is my end. The idea of eternal return and intrinsic self-renewal. I am not quite a mystic, but many of my favourite poets were.

Now, the other day I wrote about labyrinths, another favourite topic, and quoted myself (although, ironically, I had forgotten from where): “an exit to the labyrinth marked entrance to the labyrinth”. Moreover, in the

catalogue to an exhibition on labyrinths that I attended in Barcelona last year, there is a short essay by Umberto Eco, in which, after discussing the difference between the uni-cursal labyrinth (in which there is only one route in and out, as in the illustration above) and the multi-cursal labyrinth or maze or Irrweg (in which there are alternative paths, all leading to dead ends: you can make mistakes, and may have to retrace your steps, but you will always be able to get out) he proposes a third type of labyrinth, the network, in which each point can be connected to any other point, which makes it possible to travel around for ever. And you never get out of the network: you keep going round and round inside.

This is all good, because leafing, as I am, through Marie-Louise von Franz’s excellent Alchemy, I come across the following:

“One must remember the Ouroboros, the tail eater, where the opposites are one: the head is at one end and the tail at the other. They are one but have an opposite aspect and when the head and the tail, the opposites, meet, a flow is born, which is what the alchemists meant by the mystical or divine water, which is described as the meaningful flux of life.”

So, both the ouroboros and the labyrinth have served as representations of energy, of flow, and of the questing human soul, or at the very least as symbols of regeneration. They are linked in profound and deeply sympathetic ways.

And then, as if to confirm the last happy thought, I come across this fabulous video, titled Ouroboros. It seems a good place to leave these thoughts hanging.